Language matters: The specific terms used to describe harm reduction services may make a big difference in the public’s acceptance and support of them

Despite evidence that supervised consumption sites (also called “safe injection facilities”) reduce overdoses and enhance the health of people who inject drugs, they remain illegal in the United States. In this study, authors show that public support is increased for this intervention simply by using the term ‘overdose prevention site’ instead of ‘safe consumption site’.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Drug overdoses were responsible for 70,237 deaths in 2017 (approximately two-thirds of these from opioids), and the drug overdose death rate has nearly quadrupled since 1999, claiming more lives than traffic accidents and homicides combined. Harm reduction strategies, which aim to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use, have emerged as important interventions to reduce overdose deaths.

Some of the harm reduction strategies that have been implemented in the United States include syringe service programs and targeted naloxone distribution. Strong ideologies and stigma have hindered the implementation of these evidence-based interventions in many parts of the United States. Specifically, stigma may hinder service implementation by decreasing public support for harm reduction strategies and increasing public support for punitive policies.

A harm reduction strategy that is used in Europe, Canada, and Australia, but is considered illegal in the United States, is a supervised or safe consumption site (also known as a supervised injection facility or an overdose prevention site), where a person who uses drugs can consume previously purchased drugs in a facility under medical supervision without legal ramifications. Public attitudes toward “supervised consumption sites” might be more negative because this way of describing such venues may elicit the idea that they are somehow promoting drug use or “enabling” and perpetuating it, and thus ultimately not helping those they intend to serve. In the current study, Barry and colleagues investigated whether public support for these services might be enhanced if they were, instead, referred to as “overdose prevention sites.” Findings from this type of analysis could inform how public messaging campaigns might increase support for these potentially life-saving services that have promising data to support their utility but have not garnered widespread support in the United States.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

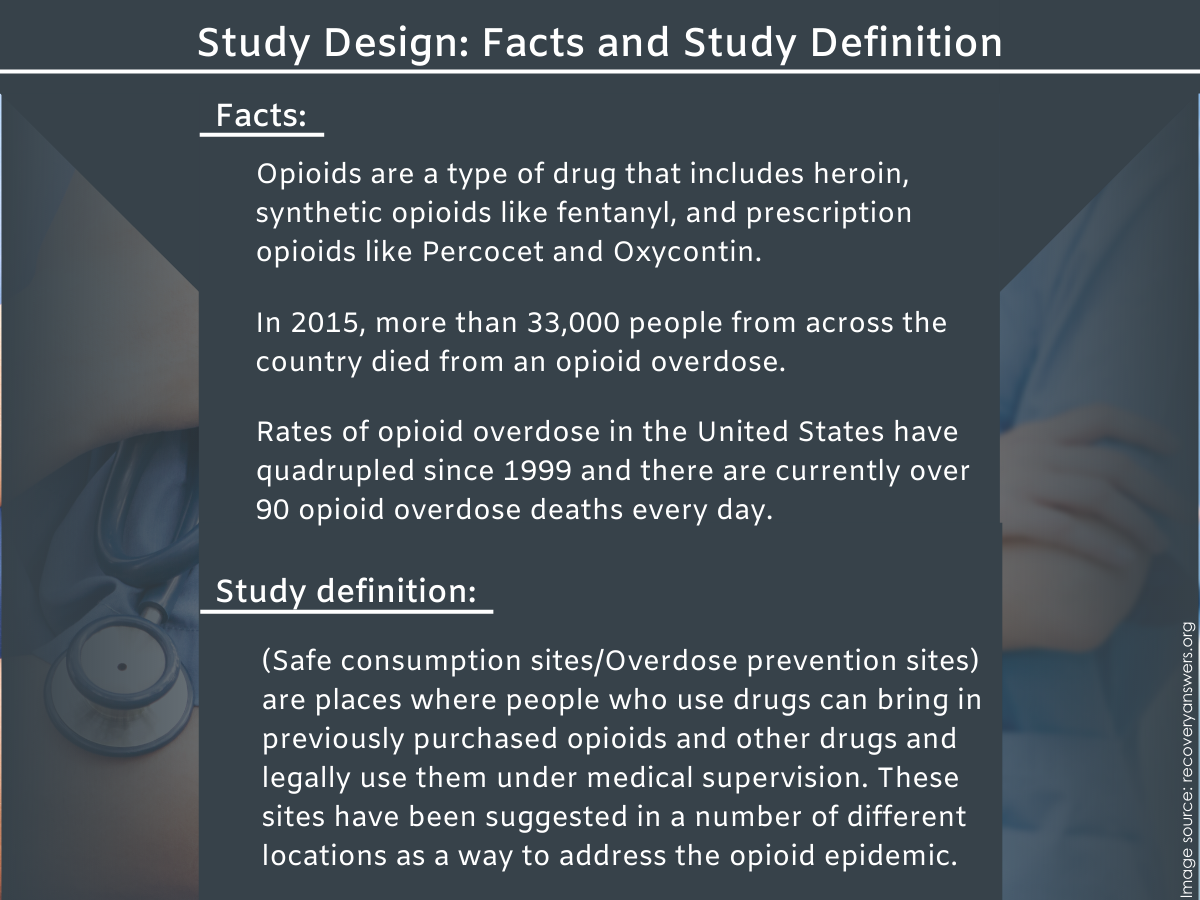

This study used two web-based surveys of 2,014 participants who were presented with three facts about opioids and opioid-related overdose deaths. Then, half were given a definition of a safe consumption site whereas the other half were given the same definition except that ‘safe consumption site’ was changed and described instead as an ‘overdose prevention site’. Participants were then asked if they supported the legalization of safe consumption sites (or overdose prevention site). Sociodemographic information was also collected.

Figure 1. Participants read three facts about opioids and opioid-related deaths and were given a definition about harm reduction services, but the harm reduction services were specifically referred to as either ‘overdose prevention sites’ or ‘safe consumption sites’. The varying definition was the independent variable in the study design, intending to gauge the participant’s response to the intervention based on how it is framed.

Authors used an opinion research firm to conduct the survey, which used statistical techniques to ensure that the estimates were representative of the United States population, ages 18 and over. In addition to estimating overall public support for legalization, the authors analyzed public support by the respondent’s age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, and state of residence. Particular to state of residence, respondents were divided into states with low, medium, and high overdose death rates. The web-based surveys were done at two different time periods: a total of 1,004 people completed the survey using the term ‘safe consumption site’ in July 2017, with a completion rate of 70%, and a total of 1,010 people completed the survey using the term ‘overdose prevention site’ in November 2017, with a completion rate of 59%.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The American public is more likely to support services called “overdose prevention sites.”

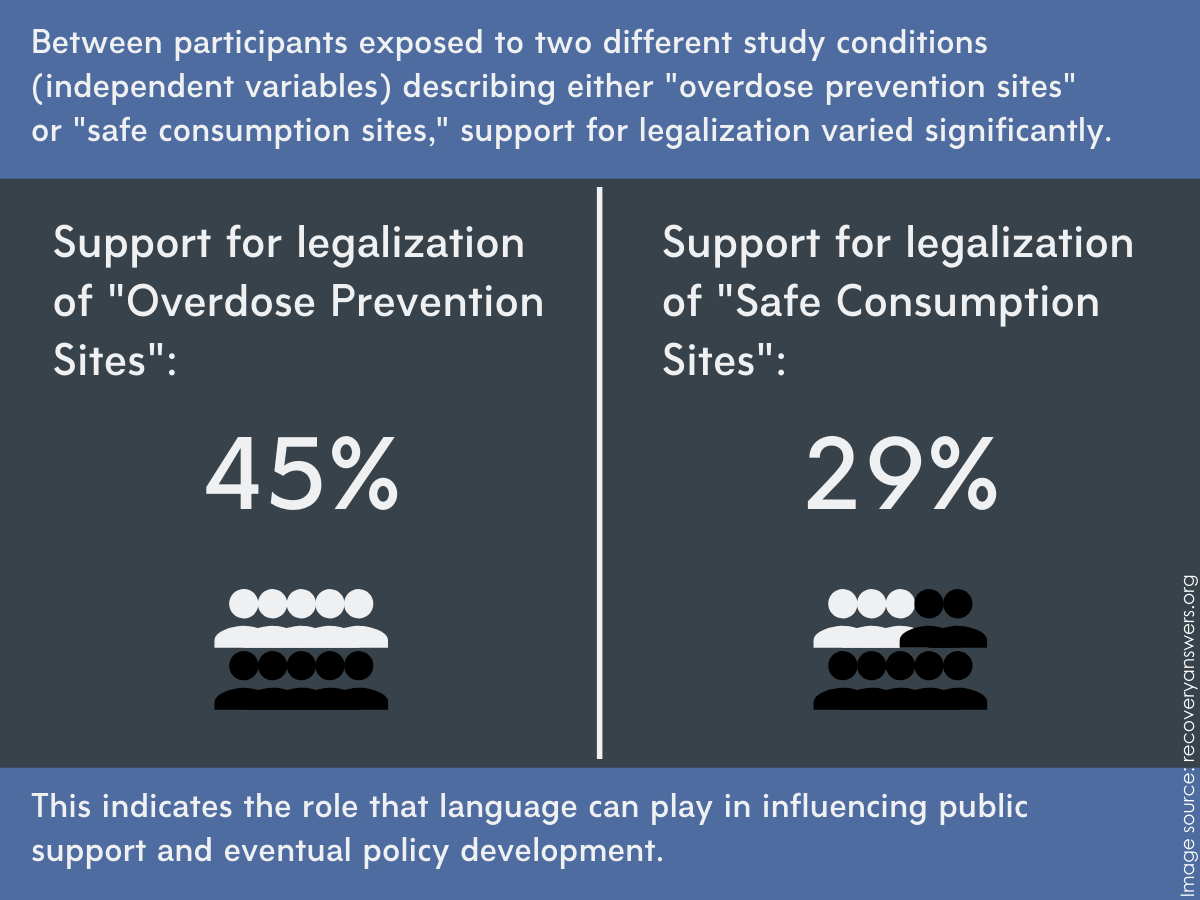

Forty-five percent of respondents supported legalization of the services when referred to as “overdose prevention sites” whereas only 29% of respondents supported legalization of the services when they were referred to as “safe consumption sites,” a statistically significant difference of 16 percentage points.

Figure 2. Differences in support for harm reduction services vary significantly depending on the way that they are described/framed.

The term “overdose prevention site” garners more support across different ages, racial/ethnic groups, characteristics of the state of residence, and political party affiliations.

Public support for the services when referred to as overdose prevention sites was significantly higher among most age groups (with the exception of ‘ages 30-44’), most race and ethnicity groups (with the exception of ‘non-Hispanic Blacks’), most educational levels (with the exception of ‘less than high school’), and most income levels (with the exception of ‘less than $25,000 per year’), compared with public support when they were referred to as safe consumption sites. Greater support for the services when referred to as overdose prevention sites also held irrespective of participants’ gender, the region of the United States in which they live, and their identified political party. The pattern of greater support for overdose prevention sites was true whether the participant lived in a state with a low, medium, or high overdose death rate.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study showed that public support for ‘overdose prevention sites’ among US adults (45%) was 16 percentage points higher compared with public support for ‘safe consumption sites’ (29%). This finding was the same across nearly all sociodemographic categories and was regardless of the overdose death rate of the respondents’ state of residence. The study demonstrates that simply changing the name of an intervention with only modest support may provide a sizeable boost to public support for its legalization and implementation.

Respondents may be more inclined to the idea of an ‘overdose prevention site’, which uses a consequence frame (meaning that the term stresses that people are dying as a result of using drugs), whereas the term ‘safe consumption site’ may be viewed as making an illegal activity safer. As a strategic communication approach, framing language in the context of substance use disorders that can reduce stigma and overcome ideological barriers has the potential to increase support for public health-oriented policies and decrease support for punitive policies.

We know that words matter in describing highly stigmatized conditions like substance use disorders. Original experimental research from the RRI has shown that, among the general population and specifically among mental health clinicians, using the term ‘substance abuser’ compared with the person-first term ‘person with a substance use disorder’ increases stigma. Other research has shown that implicit bias also exists between these two terms. Language plays an important role in framing how society thinks about substance use and recovery. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

Of note, the results also show that, regardless of whether the term ‘overdose prevention site’ or ‘safe consumption site’ is used, the majority of the public does not support a policy intervention that is supported by evidence, highlighting persisting obstacles to garnering widespread support for a public health approach to opioid and other drug use disorders. This is striking given that “overdose prevention site” from its clear terminology is obviously intended to prevent overdose and possible death, yet a majority of Americans still seem opposed to providing such sites.

Simply providing evidence on the benefits of an intervention in the context of substance use is unlikely to sway public opinion to achieve majority support. Therefore, more types of studies are needed to better understand people’s beliefs and attitudes toward individuals with substance use disorders so that communication campaigns and dissemination of evidence-based interventions are maximally effective.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- We cannot be absolutely sure that greater public support for legalization of the services was caused by a shift in the terminology alone, as the study did not randomize participants to each of the different wordings and the two web-based surveys were done three months apart. During this time period, events, news articles, or political debates may have influenced public opinion. Thus, individuals who took the second survey where services were referred to as “overdose prevention sites” were also potentially exposed to these events, news articles, and political debates, for example, while those who took the first survey where services were referred to as “safe consumption sites” were not exposed to these events. This is a threat to the internal validity of the study, reducing confidence somewhat that the shift to using “overdose prevention site” alone was responsible for the greater support for legalization. This particular threat to validity, where different events and context over time may influence study outcomes, is known as a “history” confound (as it is confounded by time).

- The sample frame of participants eligible to be picked for this web-based survey covered 97% of households. This means that some households were not eligible to be selected for the survey and other groups of people like those that are homeless, incarcerated, or institutionalized are also not eligible, thus affecting the national representativeness of this study.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed, through a web-based survey, that adults in the United States were significantly more likely to support ‘overdose prevention sites’ compared with ‘safe consumption sites’, even though both of these terms refer to the same intervention. This was the case regardless of the overdose death rate of the respondents’ state of residence and across most sociodemographic groups. The study strongly suggests that simply changing the name of a controversial intervention can significantly increase public support for its legalization and implementation. Language matters: the words family and friends use around substance use can influence what the general public views as potentially effective drug policies and how individuals with a substance use disorder feel they are perceived and supported. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see RRI’s Addictionary®.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed, through a web-based survey, that adults in the United States were significantly more likely to support ‘overdose prevention sites’ compared with ‘safe consumption sites’, even though both of these terms refer to the same harm reduction service. This finding was found regardless of the overdose death rate of the respondents’ state of residence and across most sociodemographic groups. The study strongly suggests that simply changing the name of a controversial intervention can significantly increase public support for its legalization and implementation. Language matters when speaking about substance use disorders. Using stigmatizing words can prevent individuals with substance use disorders from seeking treatment and, more broadly, from evidence-based public health interventions being supported by the general public. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

- For scientists: This study showed, through a web-based survey using a vignette, that a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults were significantly more likely to support ‘overdose prevention sites’ compared with ‘safe consumption sites’, even though both of these terms refer to the same intervention. This finding was found independent of the overdose death rate of the respondents’ state of residence and across most sociodemographic groups. However, participants were not strictly randomized to the two terms, and historical confounding was likely present, increasing the potential for bias. Authors illustrate that simply changing the name of a controversial intervention may significantly increase public support for its legalization and implementation. Stigma, especially around language, and its related costs is a nascent and important field of study. More research is needed to develop interventions and public health campaigns to reduce stigma as well as measuring the impact of stigma on society. Also, research at the intersection of politics, public health, and substance use is desperately needed to overcome ideological stigma-related barriers that hinder the implementation of evidence-based policy interventions. Another area of interest highlighted by this study’s findings is to understand why non-Hispanic Blacks and both people of the lowest educational attainment and household income level were not affected by the word change.

- For policy makers: This study showed, through a web-based survey, that adults in the United States were significantly more likely to support ‘overdose prevention sites’ compared with ‘safe consumption sites’, even though both of these terms refer to the same intervention. This was the case regardless of the overdose death rate of the respondents’ state of residence and across most sociodemographic groups. Authors illustrate that simply changing the name of a controversial intervention can significantly increase public support for its legalization and implementation. Policymakers should prioritize research and media campaigns that reduce stigma. With less stigma surrounding people with substance use disorders, individuals with this condition are more likely to seek help and public health-oriented policies will more likely be supported whereas punitive policies will not. Also, it is vital to use a communication strategy when garnering support for a policy intervention that has been historically controversial, even if the policy has strong evidence to support it. In addition, as highlighted by the findings of this study, policymakers should be aware that differing political ideologies can also be a barrier to legalizing an evidence-based policy intervention. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary®.

CITATIONS

Barry, C. L., Sherman, S. G., & McGinty, E. E. (2018). Language matters in combatting the opioid epidemic: Safe consumption sites versus overdose prevention sites. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1157-1159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304588