How to refer to individuals with heroin use disorder: A person-centered perspective

The language to use when referring to individuals with substance use disorder has been an area of much debate and increasing research interest. But what do people suffering from substance use disorders themselves prefer? This study helps provide some answers.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In an effort to reduce the stigma associated with addiction, clinical and research communities, federal agencies, and international health organizations encourage the use of non-judgmental, person-centered, respectful, and uniform language to describe individuals with substance use disorders. Research shows that person-first language (e.g., individual with a substance use disorder) is more likely to evoke a public health, rather than punitive, response toward those who use alcohol and other drugs. Existing research on language used to describe drug addiction, however, has focused largely on perspectives of the general public and health-care professionals, and to a lesser extent those in addiction recovery. To date, no studies have examined language preferences among those individuals with current substance use disorder. To address this gap in the literature, the authors of this study surveyed individuals initiating an inpatient opioid detoxification program (colloquially referred to as ‘detox’) in the northeastern United States about their language preferences for describing and talking about individuals with opioid use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a qualitative study surveying 263 individuals entering inpatient opioid detoxification. Participants were predominantly male (74.5%), white (81.4%), and many (66.2%) had injected drugs in the past 30 days. The authors approached consecutive individuals presenting to a detoxification unit in a Massachusetts hospital between October 2017 and May 2018. Three hundred and eighteen people were approached, 26 refused study participation or were discharged before staff could interview them, and individuals who did not report heroin use in the past 30 days were excluded, leaving a total of 263 people for the final analysis. Participant opinions were surveyed during a 15-minute, non-incentivized, face-to-face interview administered by non-treating research staff.

The survey had two parts. First, using an open format response, participants were asked: “What term or label do you use to identify yourself (in your own head)?”. Subsequently, they were asked if they used the same label or another, and if so which one, when talking to others who use drugs, drug counselors, doctors, family, and at 12-step program meetings. The authors coded open format ‘other’ responses into five categories: ‘addict’, ‘user’, ‘slang’ ‘other’, and ‘NA or missing’. Study participants were also asked: “If you could choose how other people refer to you, which of the below terms would you prefer?”. They were read 12 options and provided with an open format option of ‘other’. The 12 terms were as follows: Heroin addict, heroin-dependent, heroin abuser, heroin misuser, heroin user, person with heroin addiction, person with heroin dependence, person who abuses heroin, person who uses heroin, person addicted to heroin, person with heroin problem, or person who uses drugs. Participants were instructed to rate each label with a number from 1 (‘I would never want to be called this’) to 7 (‘I would prefer to be called this’).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

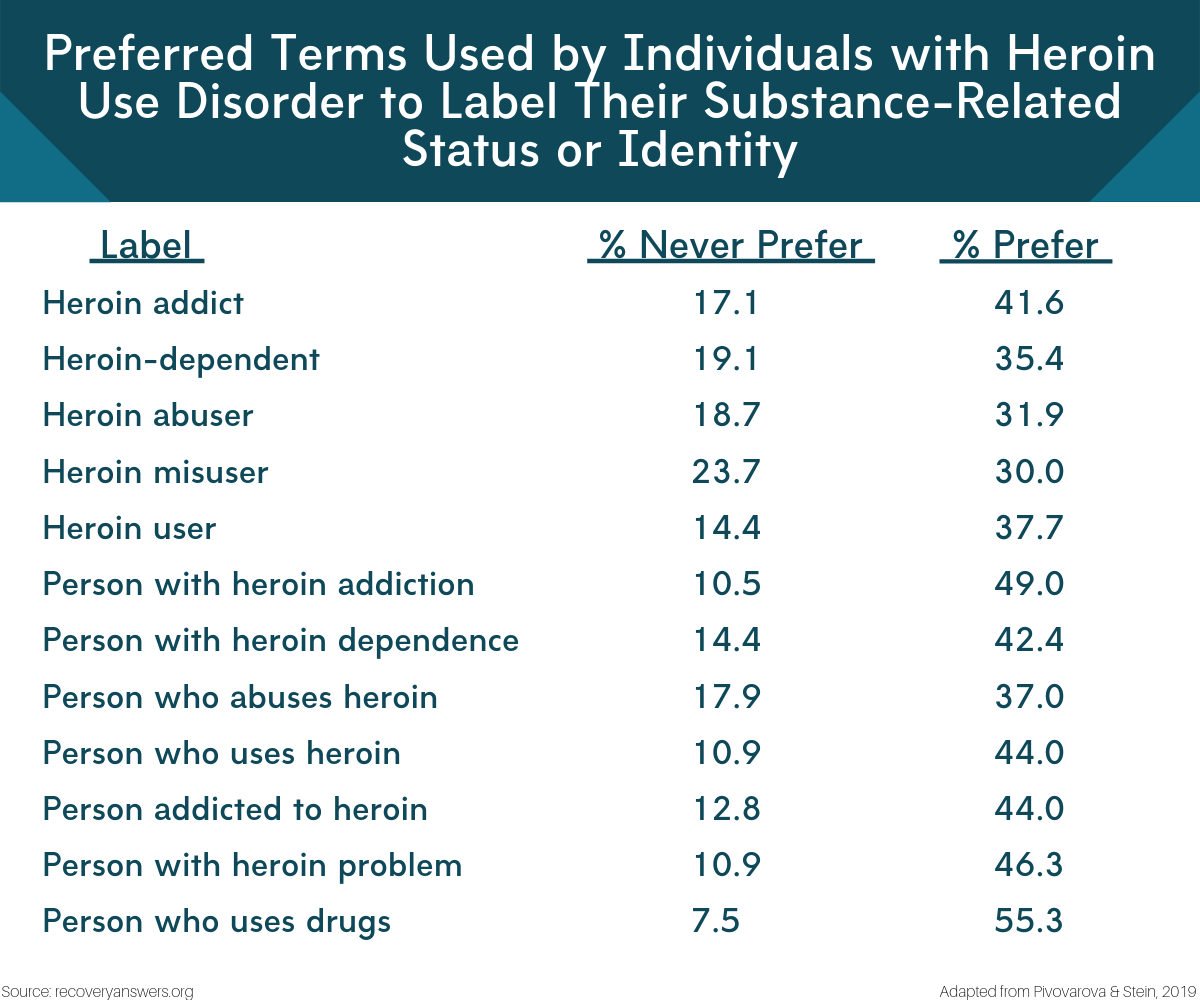

Figure 1.

The majority of participants endorsed using certain terms guidelines suggest we avoid.

The most commonly used term across communication contexts was ‘addict’, with around 70% of participants reporting using the term ‘addict’. Additionally, around 80% used ‘addict’ when interacting with counselors, doctors, or in 12-step programs. Slang terms like ‘junkie’ were somewhat more likely to be used when self-referencing when speaking to others who use drugs, though rates were fairly low (~15%).

The term ‘addict’ was also much more likely to be used when individuals were referring to themselves when speaking with others who use alcohol and other drugs, and family members. versus when speaking with counselors, doctors, or in attendance at 12-step meetings.

Participants expressed a strong preference for person-first labels.

The most undesirable term rated by the prompt, ‘I would never want to be called this’ was ‘heroin misuser’ (23.7%), followed by ‘heroin-dependent’ (19.1%). The preferred label was ‘person who uses drugs’ (55.3%). The next most preferred term was ‘person with a heroin addiction’ (49.0%). Interestingly, while 17.1% of the participants indicated they would never want to be called a ‘heroin addict’, 41.6% said this was a preferred label for them.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Individuals with a substance use disorder are less likely to utilize addiction treatment services if they perceive higher stigma toward individuals with substance use disorders. Addressing the stigma associated with addiction is therefore of critical importance. One fundamental way stigma can be addressed is through changing the language we use to talk about addiction, which includes many pejorative and judgement loaded terms that lack any diagnostic specificity. At the same time, individuals with, and in recovery from, substance use disorder have appropriated some of these terms and commonly use them for self-reference. Some of this may be related to internalized stigma and the negative and remorseful view that addicted individuals can often have of themselves.

The findings of this paper are interesting in that they highlight how terms that are avoided by professionals due to their stigmatizing nature are commonly used by people with addiction and in addiction recovery. At the same time, many participants in this study expressed opinions about terms that align with existing professional guidelines about appropriate language. For instance, 41% of participants said they prefer the term ‘addict’, a term avoided by treatment professionals because of its potentially stigmatizing nature. Only 17% of participants said they would never want someone to refer to them with this term. Conversely, 55% of participants indicated they would prefer to be referred to as a ‘person who uses drugs’, a term preferred by treatment professionals because it is person-centric, and less stigmatizing. Notably though, around 7% of participants said they would never want to be referred to this way. Perhaps as surprising, 24% of participants indicated they would never want to be called a ‘heroin misuser’ (24%), and only 30% said they’d prefer this. In contrast, ‘heroin abuser’, another term experts advise avoiding, was about equally as preferred (32%), but less participants endorsed never wanting to be referred to in this way (19%).

There are practical implications about which labels individuals use to describe themselves and when referring to others. As noted by the authors, transitioning to what could be colloquially defined as a ‘non-addict identity’ is a challenging process requiring re-interpretation of one’s sense of self and development of a recovery narrative. All participants in the study were early on in their recovery (within days of having last taken heroin). Accordingly, it may have been too early in their recovery to identify themselves in terms other than ‘addict’. In this study, the term ‘junkie’ was the most commonly used slang term. Previous literature has documented that individuals who take heroin describe the term ‘junkie’ as shameful and associate it with having less control over drug use and worse functioning than those who identify as ‘users’ or ‘addicts’.

Taken together, findings suggest that there is variability in preferences about how individuals who take drugs and are initiating substance use disorder treatment want others to describe them. Providers and family members should be careful with using any labels beyond a person’s name. It may be best to directly inquire what term an individual prefers.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the authors note, all individuals in this study were early on in their recovery (within days of having last taken heroin). As such, the preferences expressed by the participants in this study may not reflect the preferences of individuals in longer-term recovery from opioid use disorder.

- Relatedly, this study was conducted at a single site in Massachusetts, USA. It is possible that peoples’ preferences differ by geographical location (e.g., city, state, country).

- All participants in the study were early on in their recovery (within days of last opioid use), which likely influenced their responses. It is probable that individuals in long-term recovery would not endorse all these language preferences.

- Finally, the cohort was of predominantly White men. It is likely that language preferences differ for women and across different races and ethnicities.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Findings from this paper highlight the breadth of language preferences individuals with current opioid use disorder endorse. Individuals with addiction are encouraged to share their individual language preferences with their providers, and family members should generally use language preferred by the individual. At the same time, previous work shows individuals in recovery from addiction often don’t like terms like ‘addict’. The use of such terms to describe individuals in opioid use disorder recovery is possibly complicit with a negative, self-deprecating narrative individuals with addiction have internalized due to the stigmatization of those with substance use disorder. Regardless, person-first language is most preferred by individuals in active addiction through long-term recovery (e.g., ‘a person with an addiction’ vs. ‘an addict’) and should be used whenever and wherever possible.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Findings from this paper highlight the breadth of language preferences individuals with active opioid use disorder endorse and reinforce the importance of consulting with primary stakeholders on matters affecting them. Findings also highlight the importance of asking patients what language they would prefer their providers use to discuss addiction. At the same time, previous work shows individuals in recovery from addiction often express dislike for terms like ‘addict’. By using such terms to describe individuals in opioid use disorder recovery, it is possible to be complicit with a negative, self-deprecating narrative the individual with addiction may have internalized due to stigmatization. Findings from this paper highlight that regardless of the specific terms used, person-centric language appears to be widely preferred by individuals with active opioid use disorder, which is consistent with preferences of those in substance use disorder recovery.

- For scientists: Findings from this paper highlight the breadth of language preferences individuals with active opioid use disorder endorse and reinforce the importance of consulting with stake holders on matters affecting them. The use of a community-based participatory action research approach, which incorporates perspectives from individuals being studied directly into the research, may identify the most appropriate terms to use to minimize stigma and its negative implications. Further, research at the intersection of language, perceived stigma, and real-world behaviors like treatment and recovery support seeking is desperately needed.

- For policy makers: Findings from this paper highlight the breadth of language preferences individuals with active opioid use disorder endorse and reinforce the importance of consulting with stake holders on matters affecting them. At the same time, individuals in sustained substance use disorder recovery typically favor less stigmatizing and non-pejorative language recommended by experts, and all stake holders appear to prefer person-first language (e.g., ‘a person with an addiction’ vs. ‘an addict’). At the level of government, addiction related stigma would be reduced by avoiding pejorative, and diagnostically non-specific terms such as ‘abuse’, ‘addict’, ‘alcoholic’, and ‘alcoholism’ in legislation, and government institute names.

CITATIONS

Pivovarova, E., & Stein, M. D. (2019). In their own words: language preferences of individuals who use heroin. Addiction, 114(10), 1785-1790. doi: 10.1111/add.14699