The real stigma of substance use disorders

Does it matter how we talk about people with substance use disorder? Research finds powerful experimental evidence that exposure to certain terms at random actually induces systematic cognitive biases that may affect clinical judgements and quality of care.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Stigma is an attribute, behavior, or condition that is socially discrediting.

Illicit drug use disorder is the most stigmatized health condition in the world, with alcohol use disorder not far behind at fourth in the world, among a list of 18 of the most stigmatized conditions internationally. Importantly, degree of stigma is related to the perceived cause of the condition (if perceived not to be someone’s fault, stigma is lower) and perceived control over the condition (if perceived not to be under someone’s control, stigma is lower).

In a prior special issue of the Recovery Research Institute bulletin, we highlighted several studies related to the stigma of substance use disorders, including one which showed that portraying opioid use disorder as treatable may help reduce stigma associated with the condition.

In this study, Kelly and colleagues were interested in whether the language we use to describe individuals with substance-related problems may evoke different types of stigmatizing attitudes. The terms used to describe individuals suffering from substance-related conditions may convey different attributions their perceived cause and controllability.

More specifically, study authors tested whether describing someone as a “substance abuser” increases the likelihood of evoking more punitive attitudes, than describing the same person as having a “substance use disorder”. The term “abuse” may convey the notion that the person has control (one of the two factors associated with stigma) and therefore is engaging in willful misconduct. The term “disorder”, on the other hand, may convey the notion that there is some kind of medical malfunction at play, increasing the likelihood of evoking more therapeutic attitudes.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In a survey, 314 individuals responded to 35 questions related to how they perceived or felt about two people “actively using drugs and alcohol”. One person was referred to as a “substance abuser”, and the other was referred to as “having a substance use disorder”. No further information was given about these hypothetical individuals.

The 35 item survey questions used the stem “Which of these two individuals…”

& covered the following areas:

- Treatment (example: “…would you be more likely to recommend treatment to decrease substance use?”)

- Punishment (example: “…would you be more likely to recommend punishment to decrease substance use?”)

- Social Threat (example: “…would do something violent to others?”)

- Causal Attribution – Blame (example: “…has a problem caused by his own choices?”)

- Causal Attribution – Exoneration (example: “…has a problem that is more likely inherited?”)

- Self-Regulation (example: “…is able to overcome his problem without professional help?”)

Half of participants worked in the healthcare field, while 20% were students, 29% worked outside healthcare or were unemployed or retired, and 5% did not report an occupation. They were 31 years old, on average (ranging from 17 to 68 years old), 81% were White, 76% were female, and half had a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants felt, overall, that the “substance abuser” was:

- a) less likely to benefit from treatment

- b) more likely to benefit from punishment

- c) more likely to be socially threatening

- d) more likely to be blamed for their substance related difficulties and less likely that their problem was the result of an innate dysfunction over which they had no control

- e) that they were more able to control their substance use without help.

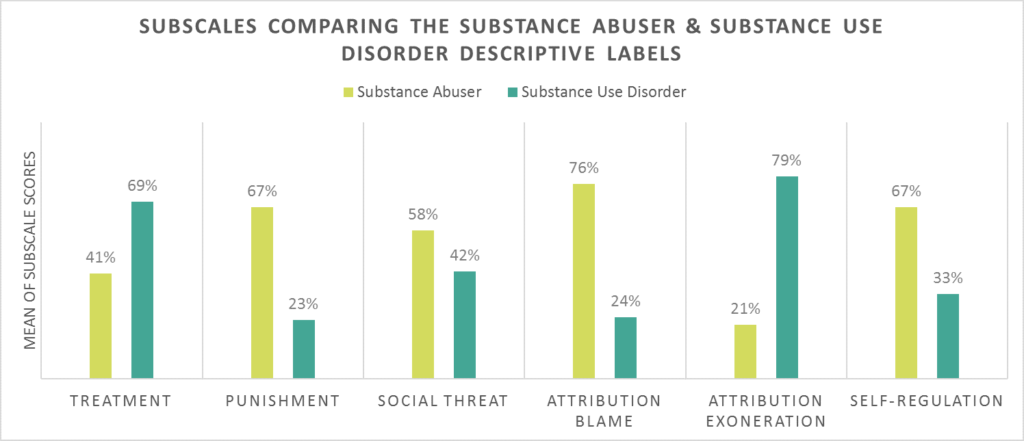

All of these differences were large in magnitude, apart from their greater level of social threat which was a medium sized difference.

In the figure below from the study, the values represent the average response rate to items making up that scale. So if the scale value is closer to 100%, participants chose that individual (“substance abuser” or “having a substance use disorder”) more often in response to items on the scale. Although the questionnaire asked participants specifically to choose one individual or the other, they were able to choose both, or could have chosen neither individual, so the values for each stigma domain do not necessarily add to 100%.

(Kelly, Dow & Westerhoff, 2010)

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

- Contextualizing the Importance of This Work: (Kelly & Colleagues, 2010)

-

In contextualizing the importance of this work, another related study is important to mention, also by Kelly and colleagues. In that study, mental health clinicians (two thirds of whom had a doctoral level degree) were randomized to receive just one of two vignettes about an individual with substance-related difficulties. The vignettes were identical except – like the study reviewed here – in one vignette, the individual was referred to as a “substance abuser” and, in the other, as “having a substance use disorder”. The questions that followed exposure to the vignette were similar to this study, though not exactly the same, and instead of choosing one hypothetical individual or another, they simply responded about their level of agreement regarding statements presented to them about the person in the vignette. For these clinicians, compared to those in the “substance use disorder” group, those in the “substance abuser” group felt the individual was more to be blamed for his problem and more in need of punishment to make a change in his substance use (e.g., “He could have avoided using alcohol and drugs” and “He should be given some kind of jail sentence to serve as a wake-up call”).

There were no differences between groups in the perception of the individual as a social threat or whether or not the individual could not control his difficulties and would benefit from treatment. Overall, then, trained mental health clinicians are less vulnerable to language-influenced perceptions of individuals with substance-related problems than individuals outside the mental health field. They are not completely immune, however, from the role language plays in how we perceive individuals with health conditions – substance-related health conditions in this case.

Taken together, these two studies are important in understanding how language may influence perceptions and perpetuate stigma.

It may be that exposure to the term “substance abuser” elicits a more punitive implicit cognitive bias whereas the term “substance use disorder” elicits a more therapeutic attitude. Use of the “substance use disorder” term may be preferable as it may be less stigmatizing. Given the common use of the “abuser” term among clinicians, scientists, policy makers, and the general public, this term may be a part of the reason why individuals seek or remain in addiction treatment.

For example, in a large, representative sample of individuals with alcohol use disorder, those who felt alcohol-related problems were highly stigmatized conditions by people they knew in their day-to-day lives were less likely to seek treatment, while those who felt alcohol-related problems were less stigmatized by these people were more likely to seek treatment. One reasonable hypothesis, then, is that if as a society, we can begin to address the stigma of substance use disorder, we can help increase rates of treatment seeking. Changing our language by dropping the term “abuser” and adopting terminology more consistent with a medical and public health approach may be one way to do this.

Overall, these studies are part of a body of literature that is helping to spur change in how language is used in the field. Recently, the International Society of Addiction Journal Editors, based in large part on these studies, provided guidance strongly cautioning against use of the term “abuse”, and advocated instead for either substance use disorder (if substance use meets diagnostic thresholds) or several variations on substance use that may cause harm, such as hazardous substance use or harmful substance use.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Individuals were not randomly assigned to receive one term or another. However, as mentioned earlier, a study with a large sample of more than 500 clinicians showed that negative perceptions of “substance abusers” remain even when a randomized trial is used.

- Also, these surveys ask individuals to respond to hypothetical individuals and scenarios. While this is a common strategy in stigma-related research, participants might not respond to people in their real lives in the same way they do on the survey.

NEXT STEPS

There are several next possible steps related to research on stigma and substance use disorder, including but not limited to the following three areas:

- First, researchers might investigate stigma related to other types of language that are considered common parlance in the world of addiction treatment and recovery, such as “addict” and “alcoholic”, as well as “clean” versus “dirty” when speaking about results of individuals’ toxicology screens.

- Second, studies might engage people in role-plays with actors portraying individuals with substance-related problems, and observe and record their actual response.

- Finally, much work is needed to understand how to reduce stigma associated with substance use disorder. Fortunately, there has been work on stigma reduction for other health conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, and researchers may be able to build on this work and apply it to substance use disorder.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance-related problems. The Recovery Research Institute “Addiction-ary” can help provide ideas on terms that are less stigmatizing. With less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek help, stay in treatment, and achieve long-term remission

- For scientists: This research provides important evidence cautioning against the use of “abuser” and “abuse” terminology on which to build. Given the methodological limitations of this study, there are several ways in which researchers can help grow this important area of substance use disorder research. Some ideas are provided in “What are the next steps in this line of research” above.

- For policy makers: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance related problems. The Recovery Research Institute “Addiction-ary” can help provide ideas on terms that are less stigmatizing. With less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek help. In a related sense, experts have used these types of studies in support of a public health, rather than a criminal justice, approach to addressing societal harms related to substance use disorders.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Language matters. This study suggests that the words “abuser” and “abuse” can evoke automatic negative thoughts about individuals with substance-related problems, even among individuals working in the health care field. The Recovery Research Institute “Addiction-ary” can help provide ideas on terms that are less stigmatizing. With less stigma surrounding alcohol and other drug use disorders, individuals with these conditions may be more likely to seek treatment.

CITATIONS

Kelly, J. F., Dow, S. J., & Westerhoff, C. (2010). Does our choice of substance-related terms influence perceptions of treatment need? An empirical investigation with two commonly used terms. Journal of Drug Issues, 40(4), 805-818.

Kelly, J. F., & Westerhoff, C. M. (2010). Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(3), 202-207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.010

*RRI researchers either conducted or were involved in this study.

*RRI researchers either conducted or were involved in this study.