When it comes to stigma and opioids, how you got started may matter.

Stigma surrounding opioids can be reduced by changes in language. For instance, referring to individuals with substance use disorder using person-first terminology. This study showed stigma may also be reduced when individuals were depicted as having less control over their initial exposure to opioids.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The current opioid epidemic has produced so many casualties. More than 2 million Americans have a diagnosable opioid use disorder and another roughly 10 million others misuse opioids to varying degrees and countless millions have been indirectly affected. Nonetheless rates of professional treatment seeking for opioid use disorder remain low at about 20%. Low treatment rates have raised questions about what barriers exist for seeking treatment and the degree to which stigma may be contributing to low treatment rates. In this case, stigma refers to negative attitudes or shared beliefs towards individuals with opioid use disorder. This study by Goodyear and colleagues focuses on how information contributes to public stigma and which groups might be most affected.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a randomized, between-subjects case vignette study with a nation-wide online survey (nonrepresentative) through a crowd-sourcing website called MTurk.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

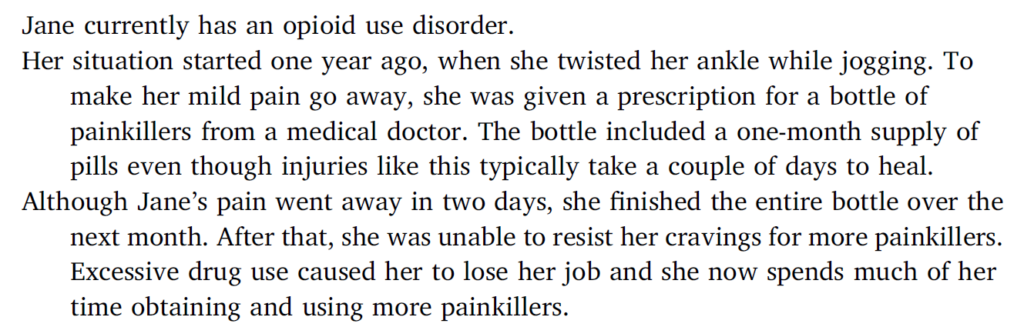

A hypothetical individual addicted to opioids was rated by 2,605 participants on four different dimensions of stigma: responsibility for condition, dangerousness, negative affect (anger/disappointment) and positive affect (concern & sympathy). Each participant was assigned to one version of a vignette where the hypothetical individual was described in three different conditions including random combinations of the conditions: 1) a male versus a female, 2) “drug addict” versus having an “substance use disorder” and 3) started by taking prescription opioids from an individual versus receiving a prescription from a doctor. An example case vignette is displayed in Table 1.

Source: Goodyear et al., 2018

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

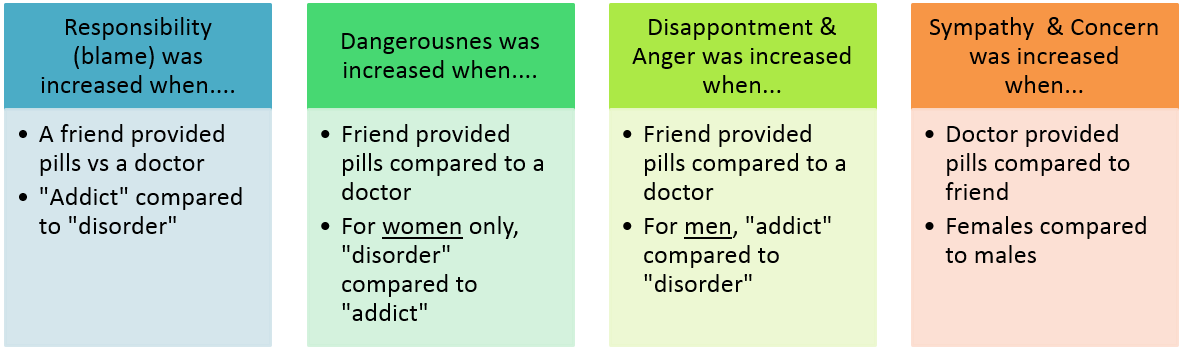

Increased stigma emerged in several conditions. Language (i.e., “addict” versus “substance use disorder”) was associated with increased stigma in 3 of the 4 outcomes considered, but not all in the same direction. In fact, the term “substance use disorder” compared to “addict” was associated with the perception that females were more dangerous. The term “addict” was associated with more disappointment and anger for men only, and more perceived responsibility for the condition. Receiving pills from an individual as compared to a doctor increased all 3 negative stigma outcomes (i.e., responsibility, dangerousness, and disappointment/anger).

The participants were asked to judge a hypothetical individual on sympathy and concern (i.e., positive affect). Females were rated with more positive affect and individuals who received the pills from a doctor were perceived with more positive affect. The results are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

All negative stigma outcomes including increased responsibility, dangerousness, and disappointment/anger and the positive outcome of sympathy/concern were influenced when the pills were obtained from an individual instead of a doctor (i.e., precipitance). The importance of precipitance is a novel finding. Individuals with an opioid use disorder may be less likely to reach out for assistance or feeling deserving of help and redemption due to the stigma associated with illegally acquiring pills. The language “substance use disorder” has helped to medicalize the disorder and pave the way for inclusion in a health care infrastructure that uses evidence-based treatments supported by reimbursement from insurance providers. Using the language of “substance use disorder” instead of “addict” has been shown to decrease blame and increase the public’s perception about the likelihood to benefit from treatment. Furthermore, addressing substance use disorders as a treatable condition has been shown to reduce negative social distance. This study highlighted that females benefit less than males from the language “substance use disorder” in terms of reducing stigmatizing perceptions of danger. In fact, women were perceived as more dangerous than men if they were describes as having a “substance use disorder” than “an addict”. Yet, in general, women compared to men may get more sympathy for having opioid related problems.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- It is unknown how the stigma found in this study translates into real world bias. For example, it is unknown how this definition of stigma effects judgements made by clinicians, family members, judges or police officers given this was a study of general lay individuals.

- Not captured in a vignette study of this nature are more nuanced details that often occur in real life. Such as when a person is initially prescribed pills from a doctor and then later obtains pills from a friend or vice versa.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study found that people with an addiction who receive pills from an individual versus a doctor are more highly stigmatized. Stigma can be a barrier for accessing professional or peer-based supportive services. Talk about these issues with a service provider or friends and family as way of addressing issues that may affect your remission and recovery.

- For scientists: This study found that people with an addiction who receive pills from an individual versus a doctor are more highly stigmatized. It would be helpful to translate stigma scores into real world bias and costs. For example, are neighborhoods with more highly stigmatizing attitudes less likely to offer evidence-based services for substance use disorder? Translating stigmatizing attitudes into actual costs to society is a step to making recovery science more useful for the general public. There is also a need to develop interventions and public health campaigns to reduce stigma. These data suggest the perceived cause/controllability, especially in the etiological course, makes a difference. In addition, men were judged with more disappointment and anger when referred to as an “addict” while women received more sympathy and concern. It is important to understand the degree to which gender biases influence the publics decision making and interactions with this population.

- For policy makers: This study investigated the role of precipitance (i.e., obtaining pills from an individual versus a doctor) in generating stigma towards individuals with substance use disorder. Precipitance affected all four outcomes included judgements of being more responsible for one’s disorder, more dangerous, more disappointed/angry, and sympathetic. Consider prioritizing research and media campaigns that destigmatize and thus reduce barriers for people seeking assistance for substance use disorder. This study has found that addressing how pills are acquired may help to reduce stigma and thus barriers for people who could benefit from services. Additionally, men were judged with more disappointment and anger when referred to as an “addict” while women received more sympathy and concern which highlights the gender bias to consider when addressing substance use disorders.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treatment providers should be mindful of how stigma affects remission and recovery for all patients. Obtaining pills from an individual versus a doctor was associated with increased stigma across all four outcomes. An implication of this finding is that individuals who suffer from addiction and obtained their pills from a doctor may have less internalized stigma and shame, but more internalized stigma if they obtained the pills from a friend. Clinicians may want to assess and address these potentially different levels of stigma in their patient as they might have implications for treatment plans and targets.

CITATIONS

Goodyear, K., Haass-Koffler, C.L., & Chavanne, D. (2018). Opioid use and stigma: The role of gender, language, and precipitating events. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, April, 185, 339-346.