12-step experiences among people taking opioid use disorder medications

12-step mutual-help organizations are accessible and effective recovery support services. At the same time, buprenorphine and methadone, viewed as the “Gold Standard” for treating opioid use disorder, are the most effective tools for reducing opioid use and opioid-related overdose mortality. Some have suggested these types of interventions cannot mix but many patients use both. This study provides insights into how people taking these medications experience 12-step groups and documents strategies to support their engagement.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

12-step mutual-help organizations are the most accessible recovery supports across the United States. Their philosophy substantially influences addiction treatment, which often incorporates 12-step meetings, and how society more broadly views substance use disorders and recovery. Abundant evidence establishes that buprenorphine and methadone are the most effective treatments for opioid use disorder and substantially reduce overdose morality and opioid use. However, these medications, often described as the “Gold Standard,” remain underutilized in the United States due to restrictive policies, limited provider availability, insurance costs and barriers, and stigma. Earlier studies have suggested people attending 12-step groups, such as NA, may encounter negative attitudes regarding the use of opioid use disorder medications, for example, the assertions that “they are just replacing one drug for another” or that people on these medications are not really “in recovery.” At the same time, an emerging body of research indicates that combining medications for opioid use disorder and 12-step mutual-help can result in greater benefit than each used separately. Given this set of facts, the presence of negative attitudes toward medication for opioid use disorders among 12-step members is of considerable concern from both a treatment and public health perspective. Understanding the nature and dynamics of this resistance is thus a public health priority and was the focus of this study.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Researchers conducted a qualitative study based on 30 semi-structured, individual phone interviews with individuals recruited from syringe exchange programs in the United States. It was part of a larger project examining barriers and facilitators to opioid use disorder medication use. The authors designed the interview questions based on a review of the literature and modified the script after feedback from two individuals with a history of using opioid use disorder medication. All study participants were asked the question: “Please describe your recovery journey, including what worked and did not work for you.” Participants who reported utilizing opioid use disorder medications were then asked to describe barriers, with interviewers explicitly prompting discussion of stigma. If participants described participating within 12-step mutual-help groups, they were then asked, “What is your experience with 12-step groups, like AA or NA, with respect to medication assisted treatment?” The question was used to explore negative attitudes directed toward the interviewees as well as negative comments that they observed in 12-step contexts. A total of 30 individuals from 8 states met the criteria for inclusion, with 86 % coming from three states. The states are not specified in the article.

The goal of this type of qualitative analysis is not to establish how frequently phenomena occur in a population, but to inform the development of research hypotheses to explore in future studies. The authors analyzed the interviews using a method called Iterative Categorization. Researchers created a preliminary code book based on the interview guide and then expanded it inductively through a review of the transcripts. The main parent codes were “12-step MOUD operationalization” and “12-step MOUD stigma responses.” The parent code “12-step MOUD operationalization” includes the participants’ reports of how they saw negative attitudes being enacted in this context. “12-step MOUD stigma responses” encompassed the ways that the interviewees navigated encounters with these attitudes. Study team members independently analyzed the interviews by assigning codes to relevant passages. They then met to compare results and resolve differences.

The authors acknowledge that the demographic information collected was incomplete. In a later effort to collect demographic information, they were able to contact 18 participants, all of whom were non-Hispanic white.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The findings consisted of two sets of experiences: forms in which negative attitudes towards opioid use disorder medications are enacted in 12-step spaces (operationalization) and 12-step attendees’ responses to negative attitudes toward opioid use disorder medications.

Interviewees described four main ways negative attitudes were operationalized.

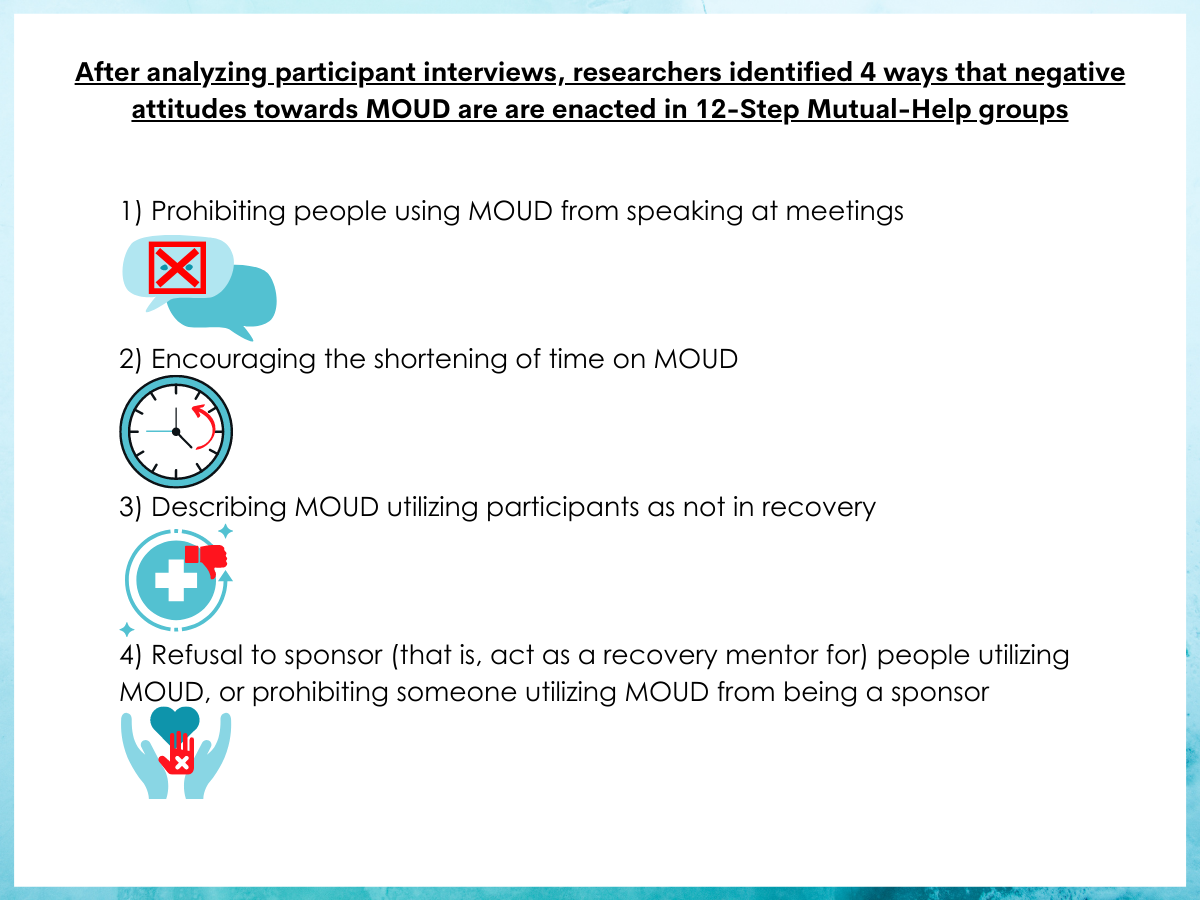

After analyzing the interviews, the authors identified four ways that negative attitudes towards opioid use disorder medications are enacted in 12-step mutual-help groups:

- Prohibiting people using MOUD from speaking at meetings

- Encouraging people to shorten the amount of time taking opioid use disorder medications

- Describing people utilizing opioid use disorder medications as not in recovery

- Refusal to sponsor (that is, act as a recovery mentor for) people utilizing opioid use disorder medications, or prohibiting someone from utilizing opioid use disorder medications from being a sponsor

Study participants reported that these practices were justified with a number of rationalizations. Some 12- step members perceived opioid use disorder medications as “just another drug.”

Another theme was that some 12-step members accepted opioid use disorder medications for short-term detox purposes but did not see it as a legitimate path to recovery.

An additional salient theme was the report that opioid use disorder medications was sometimes described as a substitute for a relying on a “higher power,” a core element of 12-step recovery philosophy.

Some interviewees described encountering these practices in online spaces as well as offline, including derisive appellations such as calling people on opioid use disorder medications “zombies.”

Interviewees described five responses to experiencing negative attitudes.

After analyzing the interviews, the authors identified five ways that people describe reacting to experiences of stigma against opioid use disorder medications:

- Anger

- Leaving the group, finding a new group, or starting a new group

- Not disclosing their use of opioid use disorder medications in meetings or only telling a sponsor

- Cognitive strategies that minimized or dismissed the importance of stigma while staying active in the group

- Utilizers speaking up in meetings

Some of these responses were described as concurrent and others consecutive, for example becoming angry and then seeking a new group. Important themes that appeared across interviews included anger at members of 12-step groups offering advice akin to that of health care professionals (which they were not qualified to give); the potential impact of shame or judgement on treatment seeking; the experience of discomfort or a clash of values due to keeping medication status secret (i.e., cognitive dissonance as a result of not disclosing their use of opioid use disorder medication in meetings within a 12-step program based on “rigorous honesty”); and finding ways to minimize or rationalize negative attitudes toward opioid use disorder medication use as a coping mechanism, for example by asserting there are a few “ignorant or mean people” in every social group.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

12-step mutual help-meetings are the most available and accessible recovery support services across the United States. As 12-step groups were among the first options available during a time when medical/professional treatment options were limited, their philosophy substantially influences addiction treatment (which often incorporates 12-step meetings) and how society more broadly views substance use disorders and recovery. Abundant evidence establishes that buprenorphine and methadone, often described as the “Gold Standard,” are the most effective treatments for opioid use disorder and substantially reduce overdose morality and opioid use. Emerging evidence, too, indicates that combining medications for opioid use disorder and 12-step mutual-help participation can result in greater benefit than each used independently, despite the opposition expressed to such medications among some 12-step members. This qualitative study is helpful in that it provides insights into the experiences of 30 individuals taking medications for opioid use disorder who attended 12-step groups, including the kinds of reactions people taking such medications may encounter. These insights can inform novel strategies for preparing people to navigate or cope with these views.

The decentralized character of 12-step mutual-help organizations (each individual meeting is self-governing) makes it difficult to address the issue of attitudes toward the medications for opioid use disorder in a coordinated way, either through education or working directly with these groups. AA, given that it focuses on alcohol addiction, has no position on medications for opioid use disorder per se. With regards to other medication use—whether anti-craving/anti-relapse medications or those used for other psychiatric illnesses (e.g., anxiety/depression)— AA publishes a pamphlet stating that its members should not offer each other advice regarding medications and that those decisions are to be made in consultation with medical professionals. However, this guidance is not always followed by individuals or groups and, as AA itself recognizes, sometimes people have been advised to discontinue psychiatric medication by AA members with serious consequences. In contrast, NA has an official position that allows local meetings to refuse participants taking opioid use disorder treatment medications the right to speak during meetings. NA also states that people on opioid use disorder medications do not meet its own definition of recovery.

Despite this explicit opposition in NA to opioid use disorder medication use, 12-step group members on these medications still benefit from participation. One study of 300 African Americans taking buprenorphine found that attending NA meetings during a six-month follow-up was associated with both a higher rate of retention in Buprenorphine treatment and a higher level of abstinence from heroin and cocaine during that same period. A multi-site, longitudinal study of 375 people taking buprenorphine found that participants win 12-step groups had 2 times the odds of being abstinent at month 18 of the study, 3 times the odds at month 30, and almost 2 times the odds at month 42 in comparison to those not attending mutual help groups. This effect was independent of the benefit of medication, and outpatient counselling was found to have no added beneficial effect. (This effect disappeared when meeting attendance was mandated.) Given possible differences between AA and NA groups toward opioid agonist medications, it is also worth noting a study showing young adults with a variety of drug use disorders, including opioid use disorder, derived similar recovery benefits from AA and NA.

Therefore, medical and treatment professionals often find themselves in the situation of recommending that people on opioid use disorder medications attend 12-step meetings while preparing them for the negative attitudes that they might encounter. This article provides an updated list of some of the ways that negative attitudes are enacted and describes ways that 12-step members have navigated these attitudes. Further research is needed to establish how common these practices are as well as the effectiveness of the affected members’ responses.

That being said, these findings suggest some specific strategies that professionals might use to prepare and support people on medications attending 12-step meetings. Clinicians and peer specialists, for instance, can legitimize feelings of anger that their clients might feel in these situations. They can recommend that clients be cautious about revealing their medication status and shop around for meetings to find more accepting groups. Research in other areas suggests that arguing against stigmatizing actions can help the people avoid internalizing negative judgements.

This article also points to topics where greater education may support people on medications for opioid use disorder. For example, the pressure to limit time on medications could be countered through education regarding the evidence that shows medically supervised withdrawal (“detox”) is not in itself a treatment for opioid use disorder and can increase short term risk for opioid overdose by reducing physical tolerance. The claim that people who take medications for opioid use disorder are not in recovery might be offset by introducing clients to the multiple pathways of recovery framework, including statements by AA co-founder Bill Wilson (on whose 12-step AA program NA is based) that “the roads to recovery are many” and his support for anything that would remediate the agony of addiction, including methadone. More research is needed on how to address other arguments against utilizing medication, for example that it replaces reliance on a “higher power.”

It is important to observe that that negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder are not universal among 12-step members. Indeed, the interviews conducted by the authors capture this diversity. One study participant described sponsoring people on medications for opioid use disorder and openly speaking about this choice. Other participants explained that 12-step groups are supposed to leave medical decisions to the professionals or asserted that judging people on medications was incompatible with 12-step philosophy. Still others describe meetings where people spoke up in defense of medications for opioid use disorder after witnessing negative comments. For example, one participant reported defending opioid use disorder medications whenever he is invited to tell his story and 12-step members coming up to thank him afterwards. The fact that members shop around for more “medication friendly” meetings itself indicates heterogeneity in how 12-step members and different meetings respond to individuals taking opioid use disorder medications.

The authors argue that the above stories represent cognitive strategies used to cope with stigma. Another plausible interpretation is that participants are reporting experiences from different contexts. This explanation would be consistent with a study based on a nationally representative sample of people in recovery that found that participation in 12-step groups does not predict negative attitudes toward opioid agonist therapy. One explanation may be the “vocal minority” phenomenon: a smaller set of particularly active or vocal 12-step members might be creating a misleading impression regarding the views of 12-step members as a whole.

Other mutual help organizations, such as Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART), All Recovery meetings (which welcome all approaches to recovery), and Medication Assisted Recovery Anonymous (MARA), do not endorse negative views about medications for opioid use disorder. Some preliminary research suggests that SMART recovery may be as effective as 12-step groups in the case of alcohol use disorder for those self-selecting into it, and members describe different mutual help organizations as supporting their recovery in similar ways.

Such newer groups, however, are less widely known than 12 -step organizations, offer fewer meetings, have a more limited geographic reach, and are often inaccessible to people living in rural areas. Additionally, their effectiveness is not as well established by research as that of 12-step mutual help. The increasing popularity of online mutual help meetings since the beginning of COVID 19 has ameliorated some of the access issues. However, some people do not have regular internet access or a safe setting in which to attend online meetings, and whether they are as effective as in person meetings (and for whom) remains an open question.

Finally, the authors follow earlier literature in assuming that stigma is the appropriate framework to analyze negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder in 12-step mutual-help contexts. However, the most influential stigma models in the social sciences define stigma as a multi-level structure involving law, institutional structure, culture, and unequal power relations as well as bias and negative stereotypes. Although some people are referred to 12-step mutual aid through court mandate, they remain a minority. More theoretical work is needed to establish whether stigma is the appropriate framework for describing negative attitudes encountered in the context of a voluntary mutual help organization, or whether another construct, such as social pressure or medical mistrust, is a better fit.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The strength of this type of qualitative research is the ability to closely examine a limited number of cases to develop new theoretical constructs or research questions. At the same time, this study utilizes a small and non-randomized sample that is not representative of the larger population of 12-step members.

- The authors do not distinguish between different 12-step fellowships in their analysis; nor do they report whether individual participants belonged to AA, NA, or some other 12-step fellowship. 12-step fellowships are independent organizations with different cultures. It may not be possible to generalize across different 12-step fellowships regarding this and other issues.

- The authors quote a number of statements by study participants that suggest that there is a diversity of responses to opioid use disorder medications among 12-step members and in different 12-step spaces. Rather than discuss the implications of these statements, they interpret this body of assertions as reflecting coping strategies used to navigate stigma at meetings and online. While compelling in some instances, this interpretation requires validation, especially since these statements appear to complicate the assumption that stigma against opioid use disorder medications is pervasive across different 12-steps contexts.

- The authors attribute stigma towards medications for opioid use disorder in 12-step meetings to 12-step philosophy. In the case of NA, there is a basis for this assumption. NA’s official statement on the question holds that meetings have the right to limit participation of individuals taking opioid use disorder medications. In contrast, AA was not historically hostile to medications for treating addiction (Vincent Dole, one of the developers of methadone, served on AA’s board of trustees), and the organization has written policies that advise AA members not to give each other advice on medications. There are likely several sources for negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder within AA and other 12-step groups, but historical evidence suggests that it too simplistic to attribute this stigma to philosophy of 12-step groups in general. Moreover, such negative attitudes have been found among individuals irrespective of their degree of prior 12-step exposure.

BOTTOM LINE

12-step mutual-help groups such as NA and AA are the most widely available and accessible recovery support services at the community level. Studies have shown that people on medications for opioid use disorder benefit from attending these groups. However, negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder, whose effectiveness is strongly supported by scientific evidence, are present in some 12-step settings. This study provides new insights into the kinds of negative attitudes people taking medications for opioid use disorders may face in some 12-step settings and suggests novel strategies for preparing people taking medications to navigate or cope with these views.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Abundant evidence establishes that methadone and buprenorphine are the most effective treatment for opioid use disorder and, when taken for over six months, substantially decrease overdose mortality and increase positive health outcomes. Studies also show that attending 12-step mutual-help meetings can benefit individuals taking medications for opioid use disorder such as methadone and buprenorphine. However, negative attitudes toward opioid use disorder medications are common in some 12-step settings, and individuals attending these meetings might face pressure to discontinue medications, resulting in reoccurrence and greater vulnerability to overdose. This article describes some strategies that 12-step members employ to navigate these negative attitudes, including shopping around for medication friendly meetings to find a more accepting space or even starting a new meeting; keeping one’s medication status hidden; speaking up in defense of medications for opioid use disorder; and recognizing that negative attitudes are not universal and that 12-step members are not health professionals qualified to give medical advice. Anecdotal reports suggest that negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder are less common in AA than NA and AA meetings might be more accepting of opioid use disorder medication use. Newer mutual help meetings, like SMART, Medication Assisted Recovery Anonymous (MARA), and All Recovery meetings (which include all recovery pathways) welcome people on medications for opioid use disorder. These meetings are now easily accessible online through platforms like In the Rooms and Unity Recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: 12-step mutual help groups such as NA and AA are the most widely available, free recovery supports at the community level. Studies have shown that people on medications for opioid use disorder benefit from attending these groups. However, negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder, whose effectiveness is strongly supported by research, are common in some 12-step settings. Treatment providers should consider referring patients on opioid use disorder medications to mutual help groups that adopt a more supportive stance towards medications, including SMART, Medication Assisted Recovery Anonymous (MARA), and All Recovery meetings. Although these organizations offer fewer meetings than 12-steps groups and are not available in every location, regular meetings can now be accessed through online platforms such as In the Rooms and Unity Recovery. For patients who prefer in-person meetings (or who lack internet access), anecdotal reports suggest that the negative attitudes toward opioid use disorder medications are less common in AA than NA, but NA participation is associated with recovery benefits. In supporting patients on medications for opioid use disorder in navigating 12-step spaces, treatment professional might recommend that they be cautious revealing their medication status, “shop around” for meetings that are more medication friendly and recognize that 12-step members are not doctors and—according to 12-step literature—they should not give other members medical advice. Although a vocal minority might give the impression that negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder are universal, research suggests that many 12-step members in fact have neutral or positive attitudes. Exaggerating the extent of negative attitudes towards medications for opioid use disorder might discourage people from accessing critical recovery supports, such as NA or AA

- For scientists: This article builds on a small number of studies that examine negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder in 12-step settings. It suggests a new typology of the ways that these negative attitudes might be operationalized and specifies some common responses among 12 -step members on medications for opioid use disorder. Although the anonymous character of 12-step mutual help fellowships makes survey research challenging, future studies should examine how common these operationalizations are among representative samples. Given evidence that shows that 12-step participation is not a predictor of negative attitudes towards agonists, it is important that future research does not generalize across 12-step mutual aid organizations and takes into account variables that might mediate attitudes, such as region, religiosity, and race/ethnicity. The identification of reactions and coping strategies towards negative attitudes is an important addition to the literature. A promising direction of research would be to develop and evaluate brief interventions based on these strategies that equipped people taking medications for opioid use disorder to navigate negative attitudes in 12-step and other spaces where such views are common. A particularly notable aspect of the evidence presented in this study is that 12-step members describe speaking in defense of medications for opioid use disorder in meetings without negative reactions, sponsoring people on medications for opioid use disorder, and challenging negative comments about medications for opioid use disorder when voiced at meetings. Although the authors do not explicitly address the issue, these divergent experiences may represent differences between 12-step meetings or organizations. Another possibility is that there has been some degree of culture change within 12-step spaces since earlier studies. This is an area of possible research.

- For policy makers: 12-step mutual help groups such as NA and AA are the most widely available and easily accessible recovery support services at the community level. Studies have shown that people on medications for opioid use disorder such as methadone and buprenorphine benefit from attending these groups. However, negative attitudes toward medications for opioid use disorder, whose effectiveness is strongly supported by multiple studies, may be present in some 12-step settings. This situation has led to concern that individuals accessing 12-step recovery supports may feel pressured to discontinue opioid use disorder medications, leading to increased vulnerability to overdose. Policy makers can encourage the inclusion of non-12-step mutual aid groups, such as SMART and All Recovery meetings (which welcome multiple paths to recovery) in settings like in-patient treatment and recovery community centers. These organizations are relatively new and still less widely known than 12-step groups. Promoting awareness of these alternatives, which are also widely accessible online, is one way to provide access to recovery supports that may be more welcoming to people on medications than some 12-step groups.

CITATIONS

Andraka-Christou, B., Totaram, R., & Randall-Kosich, O. (2021). Stigmatization of medications for opioid use disorder in 12-step support groups and participant responses. Substance Abuse, 43(1), 415-424. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1944957