Integrating medications for opioid use disorder into a 12-step treatment program

Medications for opioid use disorder like buprenorphine/naloxone, often known by the brand name Suboxone, are life-saving, empirically supported interventions. A major barrier to their adoption in residential and other common 12-step-focused programs is the perceived tension between use of these medications – particularly agonists such as methadone and buprenorphine – and the “abstinence-based” 12-step philosophy. The authors of this study show that it is feasible to provide these medications within a 12-step oriented treatment program. They also provide a valuable first look at outcomes for the patients who participated.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications for opioid use disorder, including agonists like methadone and buprenorphine, and antagonists like naltrexone, are effective and important treatment options. Research consistently shows decreased risk of relapse and death, particularly for agonists and injectable, monthly naltrexone (often known by its brand name Vivitrol). These medications also result in improved overall quality of life. According to the most recent data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), however, less than half of individuals with opioid use disorder receive a prescription for one of these medications. There are a number of barriers to the integration of medications into treatment programs, including limited knowledge and negative perceptions of medications among patients and providers, as well as special licensing requirements for providers.

Another important barrier is the perceived disconnect between the use of these medications and the messages of 12-step programs like Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). The 12-step mutual help communities have a history of using a strict definition of “sobriety” or “recovery” which excludes those taking certain medications, such as those for opioid use disorder. NA, for example, discourages those who are taking medications like methadone or buprenorphine from actively participating in meetings. The 12-step philosophy is a central component of many professional treatment programs, and this is thought to have caused hesitation within such programs to provide medications for opioid use disorder. As a result of this disconnect, it is difficult to know whether patients would even take the medication if it were available in these programs.

This study was a naturalistic examination of what happened when a leading 12-step oriented treatment facility decided to start offering medications as part of specialized opioid use disorder interventions within their residential and day treatment programming. By tracking how many patients tried a medication when it was offered, the authors tested whether integrating these medications into 12-step facilities is feasible and acceptable to patients as well as providers. The authors also provided an initial view into patient outcomes through information gathered during routine follow up, after patients completed the initial treatment program.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a naturalistic approach, which means that they followed study participants as they made treatment decisions as they would in a typical clinical setting. The authors identified patients in the facility’s residential and day treatment programming who met criteria for moderate or severe opioid use disorder and identified an opioid as their primary substance, 253 of whom agreed to be part of this study. The authors only excluded participants who met current criteria for schizophrenia or another form of active psychosis.

All participants were enrolled in this “Comprehensive Opioid Response with the 12-Steps (COR-12)” program: a new, specialized track designed specifically for patients with opioid use disorder. This program included treatment groups focused on topics specific to opioid use disorder, such as the stigma associated with medications for opioid use disorder, the risks of relapse, and overdose reversal medications. All patients were also offered medications, including buprenorphine/naloxone, oral naltrexone, or injectable naltrexone. Medication decisions were made collaboratively with treatment providers including physicians and nurse practitioners, as would happen in typical clinical care where medications are offered.

The study authors gathered baseline information including participants’ demographic information, substance use and treatment history, and chosen medication (if any). Participants also completed measures of craving, withdrawal, and desire and intention to use substances. The authors used this information to look at whether groups of participants differed based on their decisions with respect to medication treatment.

The researchers then tracked outcomes through the facility’s standard follow up procedures, in which patients are contacted one and six months after discharge. Follow up analyses included only participants who could be reached, with 73% of the original sample completing one-month follow up, and only 57% successfully contacted at the six-month follow up. These phone follow-ups asked participants about substance use, number of 12-step meetings attended, whether participants were taking medications as prescribed (“compliance”), and cravings. Using this information, the study authors compared seven groups of participants, based on medication selection and reported medication compliance (buprenophine/naloxone compliant; buprenophine/naloxone noncompliant; oral naltrexone compliant; oral naltrexone noncompliant; injectable naltrexone compliant, injectable naltrexone noncompliant; no medication).

Participants in this study were mostly White, and the average age was approximately 30 years old. More than half (68%) were male. Nearly half met criteria for alcohol use disorder and cannabis use disorder in addition to opioid use disorder, with more than 20% meeting criteria for three or more additional SUD diagnoses. Around two thirds of participants had attended SUD treatment in the past, and most met criteria for at least one non-SUD mental health condition.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

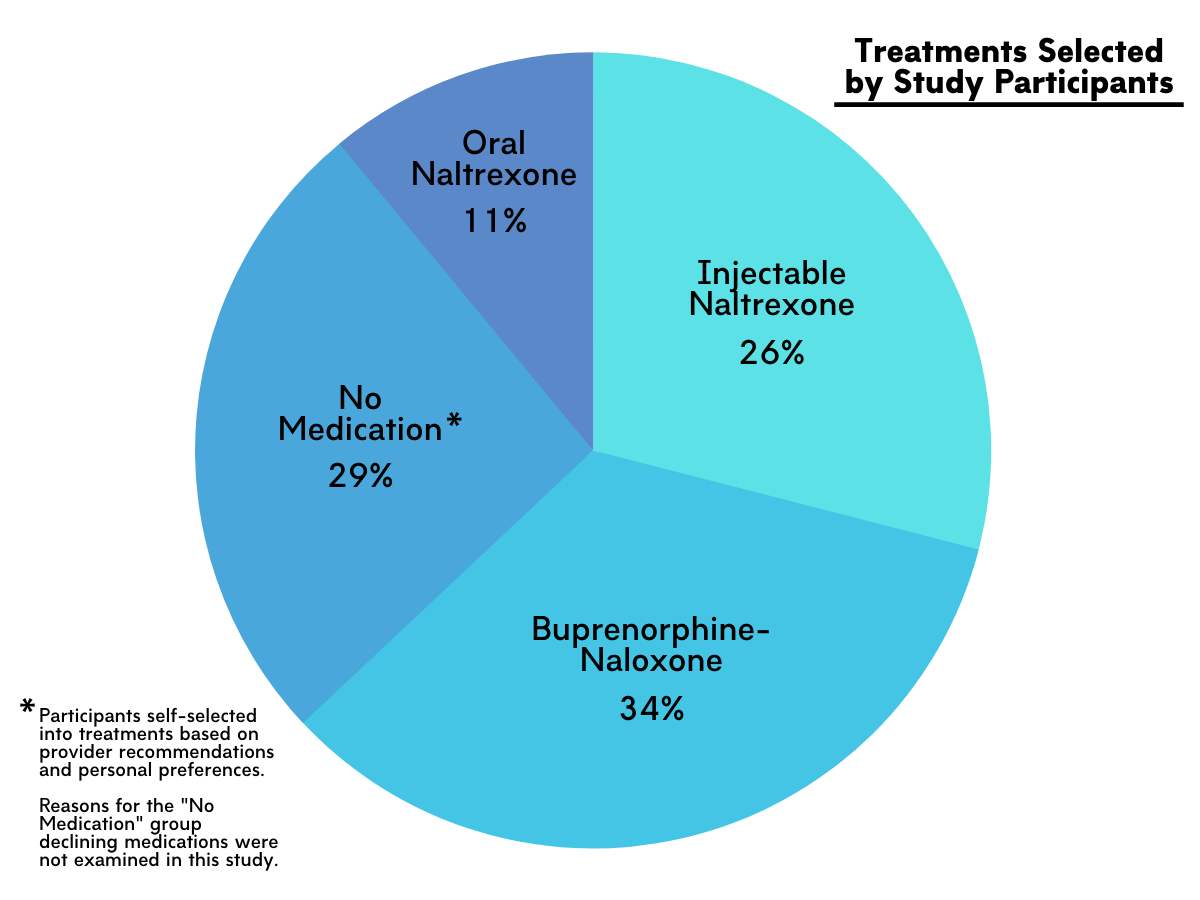

Patients in this study were about equally likely to select buprenophine/naloxone, oral naltrexone, injectable naltrexone, or no medication. Those who selected buprenorphine/naloxone also reported higher SUD severity. Of the total sample, 71% started a medication for opioid use disorder. Most participants (92%) completed the residential or day treatment program in which they were enrolled, which lasted, on average, about 40 days. Completion rates were similar regardless of medication status. Close to 80% of participants attended additional follow up treatment, with most (73%) continuing treatment within the same system.

Figure 1.

Participants who chose buprenorphine-naloxone treatment reported more severe substance use disorder symptoms, including more intense withdrawal symptoms, higher craving, and higher desire and intention to use opioids compared to those who opted out of medication or selected injectable naltrexone. The different medication groups were similar to each other in gender distribution, age, and number of co-occurring substance use disorders.

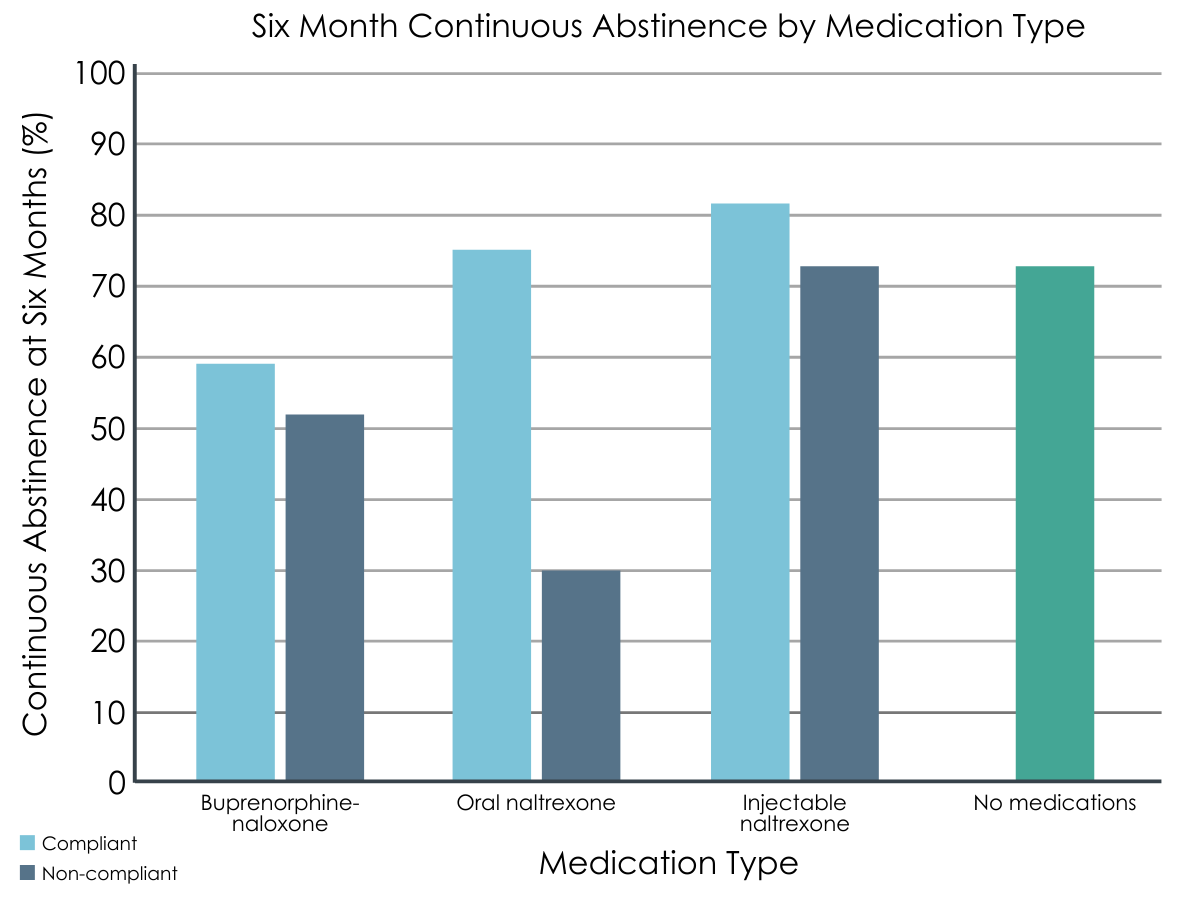

While compliance rates were similar across groups at one-month follow up, by six-month follow up, the buprenorphine-naloxone group was significantly more likely to report compliance (72%) than the oral naltrexone group (29%). Compliance for injectable naltrexone (52%) was also lower than buprenorphine-naloxone, though this difference was not statistically significant.

Overall, those who reported taking a medication as prescribed (“compliant”) were less likely to report substance use in the six months after discharge, compared to those who did not. The one exception to this pattern was the injectable naltrexone group, who were not different based on compliance at either time point. This exception is difficult to interpret, because a single dose of injectable naltrexone lasts for one month. By the six-month follow up, continuous abstinence rates were no longer different for the “compliant” versus “noncompliant” buprenorphine/naloxone groups. Participants who opted out of medications were no less likely to be abstinent than participants in most of the medication groups. The one exception, those who had chosen oral naltrexone and reported non-compliance at either time point, also fared the worst overall.

Figure 2.

Cravings also influenced substance use outcomes, with more intense cravings at treatment admission predicting substance use by six months after discharge. Participants who selected buprenorphine/naloxone also reported higher cravings at baseline, compared to other groups. Craving intensity at the two follow up points appeared to be less important for outcomes, with no associations between medication compliance or craving level, and no differences in craving intensity across the seven medication/compliance groups for either time point.

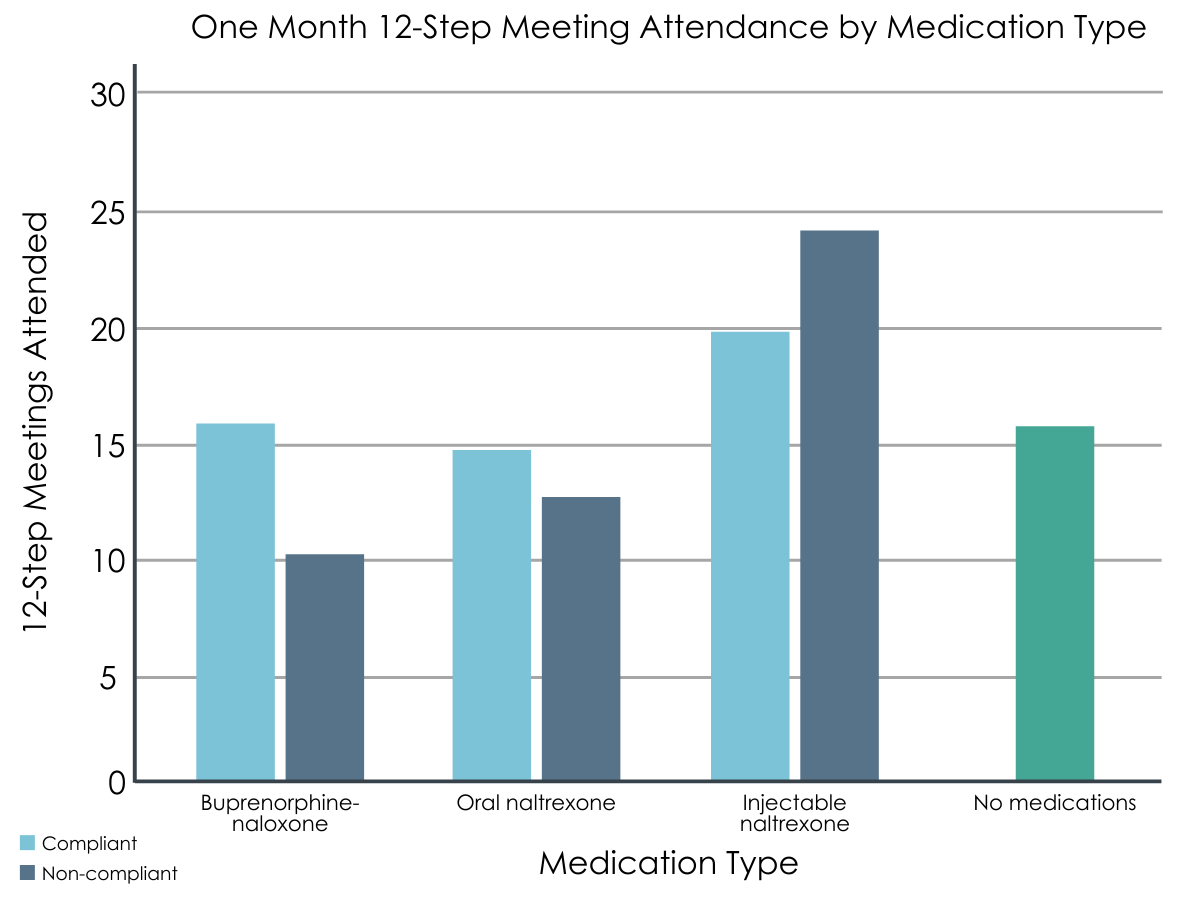

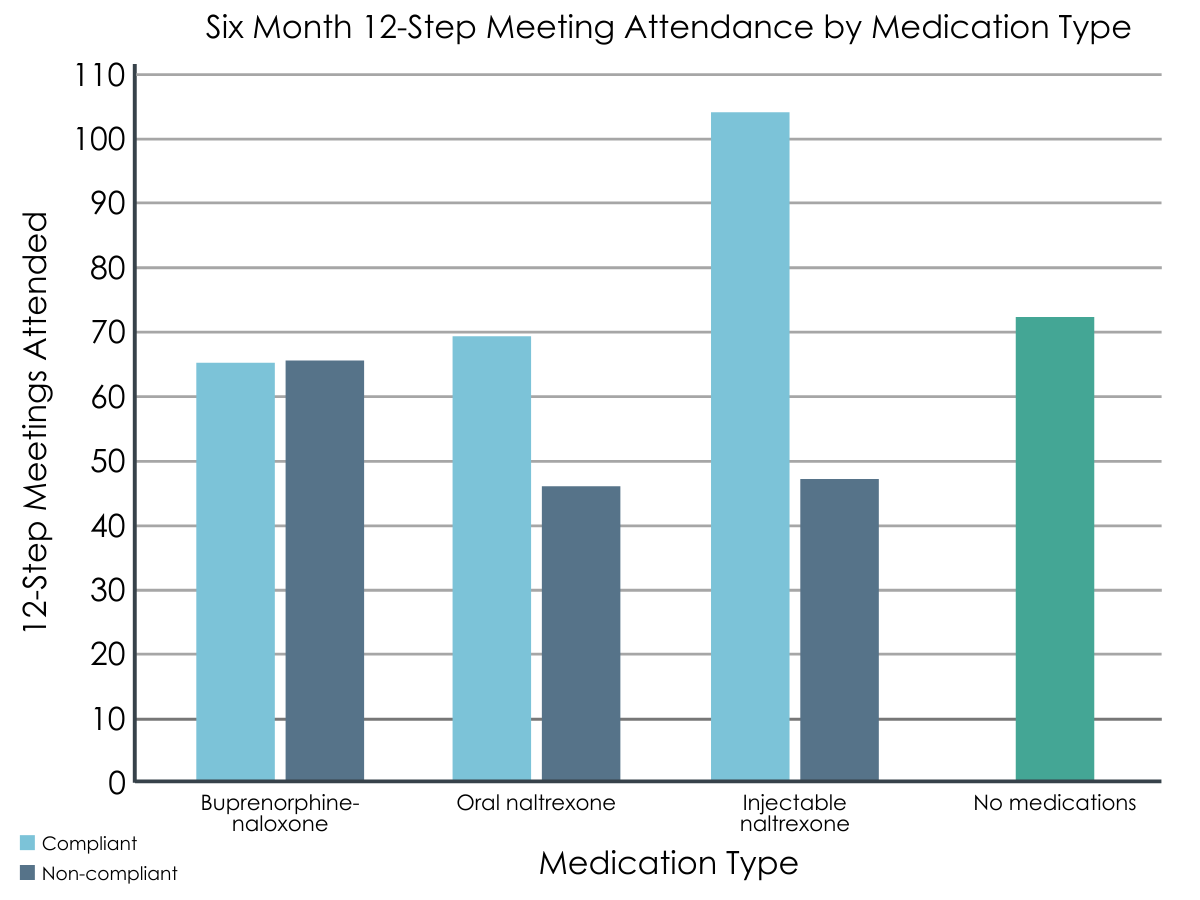

While 12-step meeting attendance was similar across medication groups during the first month after discharge, by the six-month time point, those reporting medication compliance also reported attending more meetings than those reporting noncompliance.

Given the study goal of effectively integrating 12-step treatment with medications for opioid use disorder, the researchers also asked participants how many meetings they attended during the follow up periods. To take a first look at whether medication choice influenced meeting attendance, the authors compared the number of meetings attended within each group. The number of meetings attended during the first month after discharge did not differ significantly based on medication group and ranged from an average of about 11 to 24 meetings. At six-month follow up, those who took a medication and were compliant attended more meetings on average compared to those who reported non-compliance. The average number of meetings attended ranged from 46 for the oral naltrexone/noncompliant group to 104 for the injectable naltrexone/compliant group.

Figures 3 and 4. 12-step meeting attendance tracked across one- and six-month follow-up time points, compared between medication compliance groups.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study represents a critical first step towards integrating medications for opioid use disorder into a well-established 12-step oriented treatment system. The integration of these evidence-supported treatments by a leading treatment facility makes effective use of the evidence showing their additive benefits. Importantly, with 71% of participants successfully initiated on a medication, the percent who opted out was similar to those choosing to take medications in recent studies in hospital settings perceived as encouraging of medications for opioid use disorder. The authors also reported general support from clinicians and providers during the implementation of this programming. While provider bias is worthy of closer examination, the authors noted that many had been directly affected by the overdose crisis, suggesting that the cost of the crisis made clear the importance of making all effective treatment options available.

The fact that these two empirically-supported treatments (i.e., medications and 12-step participation) are not necessarily exclusive is critical, because both are valuable for opioid use disorder. For example, another recent naturalistic study followed patients for 3.5 years after they completed a treatment study, and showed that medication and 12-step meeting attendance were two of the best independent predictors of abstinence from opioids. Another study by Monico and colleagues showed that patients who attended more meetings were more likely to take their buprenorphine medication as prescribed and to remain abstinent. Most participants in the Monico et al. study did not disclose their medication status at meetings, and about a quarter of those who did were encouraged to reduce or stop their medication. The authors of the current study indicated that the opioid use disorder specific groups actively addressed the potential medication-specific stigma that participants might encounter in 12-step groups. This may be why many participants attended 12-step meetings regularly during the follow up period, with minimal differences based on medication status.

Also, in another study that surveyed a nationally representative sample of individuals who resolved a substance use problem, any 12-step mutual-help attendance within the past three months was not related to opioid use disorder medication attitudes. Thus, it may be that only a minority, albeit a vocal one, has negative medication attitudes. Overall, more work is needed to determine how individuals taking medication experience their 12-step attending peers’ responses to their medication status when they share it, and the best approach for managing any negative responses that they experience. For the current study, we do not know whether participants attended primarily NA versus AA meetings, and it is unclear the extent to which attitudes and active discouragement or opposition to medication differ between these or other 12-step mutual-help organizations. There is evidence that attending AA is just as beneficial as NA for those whose primary substance is not alcohol. It will also be important to determine whether this integrated approach can be sustained as part of regular programming in this type of setting.

While the main goal of this study was to determine the feasibility of integrating these two approaches, the authors also reported substance use and related outcomes one and six months after participants completed the integrated program. They compared groups based on medication compliance, as previous research has highlighted theimportance of taking medications as prescribed. Consistent with this previous work, medication compliance was generally associated with more positive outcomes compared to noncompliance. Participants who selected buprenorphine-naloxone were generally more likely than other medication groups to report compliance by six-month follow-up. Until future research identifies the specific causes of these differences in compliance rates, these real-world differences in adherence are worth considering when selecting a medication for opioid use disorder.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study used a naturalistic design, which means that it followed participants who made treatment decisions as they would in a typical medical setting, and follow-up outcomes were based on self-report. The benefits of this approach include allowing participants to have autonomous choice, and more closely matching what happens in real clinical practice. One downside is that outcomes can be difficult to interpret. For example, it is possible that participants choosing medication treatment for opioid use disorder were different from those who did not in some meaningful way, and indeed they did appear to be experiencing more severe symptoms of opioid use disorder. Future work will need to examine these preliminary findings in a more rigorous manner.

- The authors reported whether participants reported using any substances during the follow up period, but did not report on opioid use specifically. While the study authors cited the abstinence-only focus of the treatment program itself as rationale for this, it will be helpful for future research to also report on opioid use outcomes, given the high risks associated with relapse to opioids in particular.

- When considering how best to integrate 12-step participation and medication treatment, meeting attendance is a critical outcome measure. For this initial feasibility study, the authors did not provide much detail with respect to the type or setting of meetings attended. There is likely to be some variability in response to medication status disclosure depending on the meetings attended, and this information will be valuable in future research. There is also evidence that active participation in meetings is important, and given NA’s stance on participation by those taking medications for opioid use disorder, future research will need to examine meeting involvement more closely.

- There was not biological verification of self-reported outcomes and the research evaluation retention rate was very low at the six-month follow-up. These are major limitations in what can be concluded about outcomes overall and especially at six months following COR-12 initiation.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that medications for opioid use disorder can be offered within a 12-step oriented program. While there is a history of separation between these two evidence-supported resources for recovery from opioid use disorder, more recent work shows that each provides added benefits when combined as part of a recovery plan. If possible, consider seeking out treatment options that provide access and linkages to both services.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: While the traditional stance is that 12-step oriented treatment programs are incompatible with medications for opioid use disorder, this study showed that it is possible to integrate this life-saving treatment within these existing treatment models. Treatment programs which provide medication for opioid use disorder should consider how to integrate encouragement for 12-step participation, and 12-step oriented programs should work to incorporate medications into their treatment offerings.

- For scientists: This naturalistic study showed that a 12-step oriented treatment program can successfully provide medications for opioid use disorder. More research is needed to determine how best to integrate these treatment approaches, including a closer examination of how best to support 12-step involvement for patients who are taking medications for opioid use disorder.

- For policy makers: This study reported on the feasibility of integrating medications for opioid use disorder into a well-known 12-step oriented treatment system. While these two approaches have long been considered at odds with one another, the current findings suggest that integration is possible. Given growing evidence supporting both approaches as well as their additive benefits, more funding will be needed to determine how best to integrate these interventions in existing treatment programs in an effective and sustainable manner.

CITATIONS

Klein, A. A. & Seppala, M. D. (2019). Medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder within a 12-step based treatment center: Feasibility and initial results. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 104, 51-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.009