Sticking with it: Predictors of continued medication use for opioid use disorder

Medications like buprenorphine, methadone, and injectable naltrexone are gold-standard, empirically-supported treatments for opioid use disorder, and if used consistently, can substantially reduce the risk of overdose and death. Taking the medication consistently for 6 months or more is often needed to produce these benefits, but research suggests most individuals have difficulty doing so. This study explored whether there were specific structural or individual characteristics that predicted sustained engagement with opioid use disorder medications.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications such as agonists (e.g., buprenorphine or methadone) and antagonists (e.g., injectable naltrexone), are first-line interventions for opioid use disorder: if used consistently, these medications can substantially reduce the risk of overdose and death and improve recovery outcomes. Yet, despite the success of the use of medications for opioid use disorder recovery, it is difficult to engage individuals in this treatment and to sustain their participation.

Research suggests that at a minimum, 6 months is needed for these benefits to accrue. Also critical is that discontinuing medication can increase one’s risk of drug overdose. Theory suggests several reasons why individuals have difficulty sustaining medication adherence over time. These include potential structural barriers such as clinical prescribing practices and insurance coverage; personal barriers, such as experiencing stigma related to use of medication for recovery; or logistical barriers, such as transportation and time constraints.

Understanding more about the factors that predict sustained engagement with opioid use disorder medications could help inform policymaking and practice that could ultimately improve the likelihood of medication adherence over time. To help increase knowledge in this regard, this study explored whether there were specific structural or individual characteristics that predicted sustained engagement with opioid use disorder medications among a national US sample of adults who were discharged from treatment during 2017.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In this study, the researchers conducted secondary data analysis using a national cross-sectional sample of treatment discharges in the 2017 Treatment Episode Dataset-Discharges (TEDS-D). The researchers examined predictors of retention – defined as 6 or more months in treatment – among episodes of specialty addiction outpatient treatment that involved one of three FDA approved medications for opioid use disorder (methadone, buprenorphine, or oral or injectable naltrexone).

The administrative dataset also included the reason for treatment discharge in the following categories: (1) treatment completed, (2) dropped out of treatment, (3) terminated by facility, (4) transferred to another program/facility, (5) incarcerated, (6) death, or (7) “other” reason.

In addition to examining the likelihood of retention for 6 months and the factors associated with retention, the researchers also conducted exploratory analyses of reasons for discharge among subsets of groups at high risk. Finally, the research team conducted sensitivity analysis to explore 12-month outcomes and to examine whether changing the transferred discharges to be categorized as equivalent to remaining in treatment (rather than dropping out) made a difference in the outcomes. The researchers included the following variables in their analysis: sociodemographic predictors (age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, housing, and veteran status), prior month arrest, location of discharge (i.e., each U.S. state, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia), and a host of clinical and treatment predictors (substance use behaviors prior to admission, age of first use, frequency of use, primary use of heroin vs. other opioids, psychiatric comorbidity, a secondary or tertiary substance problem involving alcohol, cannabis, benzodiazepine, cocaine, or methamphetamine, prior substance use treatment, referral source, and insurance).

This sample of outpatient treatment-seeking adults consisted of slightly more men (59%), ages 18–39 (63%), and non-Hispanic White individuals (66%). Almost three-quarters had 12+ years of education (72%), most lived in independent housing (77%), and were unemployed (75%). Few were veterans (2%) or had prior month arrests (4%). Most (75%) had started using opioids at 18 years or later and 54% were using opioids daily; 36% had a comorbid psychiatric condition.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Most treatments lasted less than 6 months, with the highest percentage “dropping out” of treatment compared to other reasons for discharge.

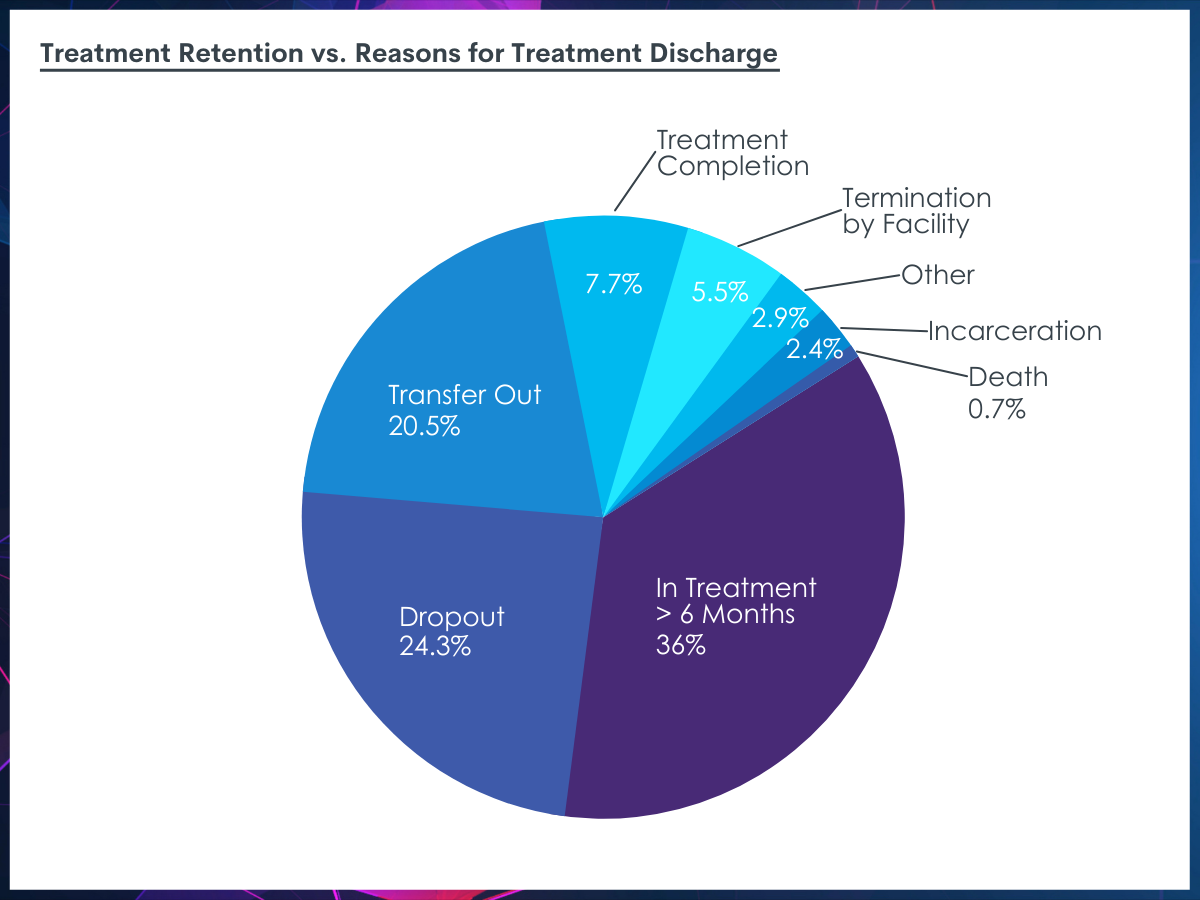

Of the total discharges in 2017, only 36% were engaged for longer than 6 months. Dropout was the most common reason for discharge (38%), followed by transfer (32%), completion (12%),

termination by facility (8.6%), other (4.5%), incarceration (3.8%) and death (1.1%).

Percentage of individuals remaining in treatment more than 6 months compared to those who dropped out for various reasons. The percentages in the figure are taken from the percentage of those who dropped out as a part of all of individuals in the study (i.e., 38% of the 64% who dropped out = 24.3% of the total study population).

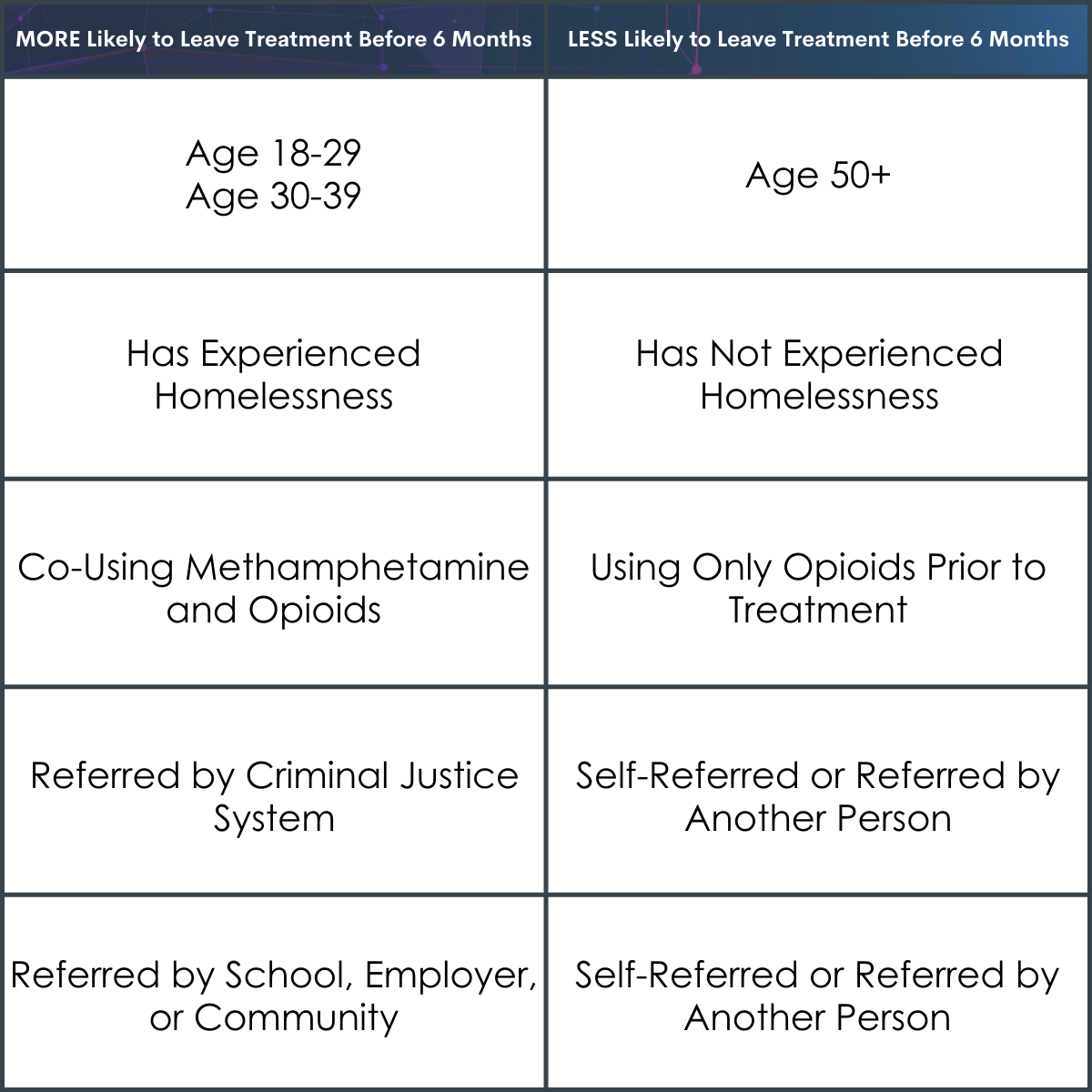

Age, homelessness, co-use of methamphetamine and referral source were the strongest predictors for treatment discontinuation by six months.

Individuals ages 18-29 and 30-39 were more likely to leave treatment before 6 months compared to individuals 50+ years old. Individuals who had experienced homelessness were also more likely to leave treatment before 6 months compared to those who had not. Those who were co-using methamphetamine in addition to opioids prior to treatment admission were more likely to leave treatment before 6 months compared to those who were not; the co-use of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine at baseline were also related to lower treatment retention but were not as risky for treatment dropout as methamphetamine. Finally, those who were referred by criminal justice or by a school, employer, or community source were more likely to leave treatment before 6 months when compared to those self-referred or referred by another individual.

There were several geographic differences between 6-month discharge rates, but these differences did not vary by state size, Medicaid expansion status, or region.

Treatment episodes reported from Arizona, Washington DC, and Puerto Rico had the highest proportion of treatment lasting longer than 6 months (58% or higher) while treatment episodes reported from Illinois, Kentucky, and North Carolina had the lowest proportion of treatment lasting longer than 6 months (<10%). Despite these differences between states, there was no clear pattern of factors that emerged as causing these state-level differences in treatment episode length.

Reasons for early treatment discharge (before 6 months) varied by risk factor.

Treatment discharges who were reported as dropping out of treatment (38.9%) accounted for the largest proportion of discharges among those under 40 (37.1%), those experiencing homelessness (43.4%), justice-referred individuals (29.9%), and those referred by school, employer, or community source sources (35.8%). Cases reported as “completed treatment” (9.2%) was most common among those referred by the criminal justice system (16.3%) and by a school/employer/community referral (11.0%). Individuals reported as terminated by the facility (7.8%) were often those who had been referred from the criminal justice system (11.5%). Treatment discharge due to incarceration, death, and other reasons (8.1%) were not linked to any specific predictors. Finally, treatment discharges due to transfer to another treatment facility (35.9%), which could suggest engagement in more intensive treatment and may not mean complete dropout from treatment, were most prevalent among individuals with methamphetamine co-use (46.6%).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The researchers of this study explored predictors of sustained engagement with opioid use disorder medication treatment among a national US sample of adults who were discharged from treatment during 2017.

Overall, retention in medication treatment was low, as the majority of participants did not continue treatment for at least 6 months. Notably, based on administrative records from respective programs, only 12% of discharges were for treatment completion while the most common reason for treatment discharge was dropout indicating that discharge was premature in many cases. As well, there were several risk factors for leaving treatment before 6 months, including homelessness and co-use of methamphetamines, risk factors that have been demonstrated as key to relapse in other research with similar populations. Also, in support of previous research, individuals younger than 50 years were more likely to have shorter than 6-month treatment episodes; indeed, being under 40 years of age was the strongest sociodemographic predictor of shorter retention. Yet, the categories of ages used (18-29 and 30-39) did not allow for a more nuanced assessment of risk by age.

The referral source was also linked to differences in treatment retention. Those referred by another individual or who chose to enter medication treatment themselves were more likely than those referred by the criminal justice system (who were about ½ as likely) or a school/work/community source (who were about ¾ as likely) to remain in medication treatment longer than 6 months. This finding suggests that those who were referred by close sources (self, other person) might be more self-motivated to engage in the treatment or had the necessary supports to do so. Alternatively, those referred by institutions may have been mandated or needed to complete treatment to avoid consequences and thus were not as internally motivated or ran into other barriers to completion (e.g., work schedule conflicted with treatment regimen). Alternatively, there were large proportions of individuals referred by external systems (i.e., school/work/community) that were designated as having completed treatment within a 6-month period. Yet, given the limitations of the data source, it is unclear what this short completion time actually indicates. That is, individuals may have had the resources to go through the program quickly and complete it within 6 months, perhaps highlighting some additional recovery capital they had access to. Alternatively, these programs could have required a 6-month episode of treatment in order for individuals to avoid the consequence of being asked to leave school or be fired from their job. Further research should examine these factors to determine whether, in fact, these system-based referral sources are introducing barriers to recovery.

There were also marked differences in the proportions of treatment discharges across the United States (ranging from 4-70%) depending on the state or district, suggesting that there are specific barriers operating in different geographic locations that affect longer-term treatment engagement rates. For example, although criminal justice referral is often associated with greater retention presumably due to greater monitoring and threat of jailtime for non-compliance with treatment, the findings in this study suggest that in some regions there may be criminal justice structures that decrease support for extended medication treatment. The current study was unable to address what these regional differences might be, but this seems an important area for future research to examine.

Specific supports for those experiencing greater vulnerabilities may be necessary. That is, those experiencing homelessness may have lower recovery capital than others and may need linkages to additional supports, such as recovery housing and recovery community centers which may also offer peer recovery support specialists, to facilitate sustained engagement with medication treatment for opioid use disorder.

While not examined here, it is possible that some individuals discontinued medication because they did not experience it as helpful. In this regard, individuals with lived recovery experience, particularly experience with opioid use disorder medication may be able to validate these concerns and encourage individuals to initiate and “stick with it” given the benefits of sustained engagement over time. As well, individuals with both opioid and methamphetamine use may have a more severe substance use disorder and/or set of associated challenges, necessitating services which more explicitly address those comorbidities. Such individuals could also benefit from a higher level of care, such as inpatient/residential treatment – this study included only individuals in outpatient care. Indeed, individuals also using methamphetamines were more likely to be reported as treatment transfers, suggesting they received other treatment services, which unfortunately could not be assessed in this analysis.

In sum, there remains a need for multiple strategies to retain individuals in medication treatment, with potential add-ons worthy of investigation including recovery-oriented clinics and linkages to mutual help groups, all supports that may need to vary by geographic context and available resources.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Because the analysis only examined cases noted as treatment discharges in 2017, there is a possible overestimation of treatment discontinuation; that is, patients that were retained in treatment outside 2017 (potentially for longer than the 12 months of available administrative data) are missing from the analysis and so it may appear there is a higher proportion of treatment discontinuation in the US. As well, the reason for treatment discharge was provided from a set of standard options in the administrative database; there may be key information missing that is important to better understanding patient discharge not available in these data.

- As with other secondary analysis on medication for opioid use disorder, there is a lot of missing detail about the purpose of the treatment (e.g., taper/temporary issue versus long-term treatment), the type of medication used, the medication dose, and return to substance use or ongoing use of substances; these are all factors that could influence how we interpret the findings.

- Other studies using these data have synthesized the data with key geographic factors, but this study did not do this; for example, the analysis did not adjust for the size of the state population. As well, approximately 28% of episodes had some missing data (including 16 states that don’t report on health insurance status); these missing data could potentially be influencing the geographic differences but cannot be examined.

BOTTOM LINE

The researchers found that among a national sample of adults in the United States who were discharged from treatment during 2017, overall retention in medication treatment was low: most participants did not sustain this treatment beyond 6 months. According to the administrative data available, only 12% of discharges were for treatment completion while the most common reason for treatment discharge was patient dropout. The key risk factors for not reaching the 6-month benchmark included homelessness, co-use of methamphetamines, and being younger than 50 years old, all risk factors that align with existing research in these populations; yet, those with documented co-use of methamphetamines were also very likely to be categorized as “dropping out” due to transfer to another treatment facility, suggesting engagement in a more intensive source of care (rather than simply dropping out of treatment altogether). Referral source was also linked to treatment retention: individuals referred by another individual or who chose to enter medication treatment themselves were more likely than those referred by the criminal justice system or school/work/community source to remain in medication treatment longer than 6 months.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Recovery from an opioid use disorder is a difficult process for many that often requires several sources of tangible and intangible support (recovery capital) to initiate and sustain recovery over time. Medication treatment for opioid use disorders can improve recovery outcomes, but only if individuals consistently receive it for a sustained period of time. Unfortunately, there are a variety of barriers to continuing medication treatment, including shame or stigma or more practical barriers such as insurance coverage and transportation to the treatment clinic. Understanding that those barriers exist and working with a family member to help identify and problem-solve these issues may be one way that families can actively support one’s recovery journey.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Although engaging patients in medication treatment for opioid use disorder can be highly effective, there may be a variety of barriers to ensuring they remain engaged; connecting them to supports and resources which address their most immediate needs is vital to building recovery capital and ensuring their continued motivation and success in recovery. Providers and systems should be part of the bridge that connects patients to these needed services and helps them to reduce barriers. It may also be necessary for clinicians to advocate for patients that are referred from certain systems which limit their length of time in medication treatment for an opioid use disorder.

- For scientists: Unlike other studies which focus on prescription data, this study examined discharge data to assess actual treatment received; yet the analysis could not account for several key predictors of retention/attrition in this treatment (e.g., type of medication and dose, return to substance use/ongoing use of substances), all factors that would improve the utility of future research. Additionally, scientists can play a valuable role in using innovative study designs to better understand the reasons and barriers to treatment continuation and assessing strategies to address these barriers. Finally, scientists that study the use of medication treatment for opioid use disorder may need to engage in further advocacy to break down the stigma and other barriers surrounding the use of medication to treat these disorders.

- For policy makers: Given the risk of drop out especially for at-risk individuals such as those experiencing homelessness, further attention to funding programs which may address logistical and access barriers, such as prioritizing housing for those with behavioral health conditions, enabling low-threshold medication for opioid use disorder through more flexible programs, and alternative payment models (e.g., bundled payments for social services and transportation) may help to improve retention for this vulnerable group.

CITATIONS

Krawczyk, N., Williams, A. R., Saloner, B., & Cerdá, M. (2021). Who stays in medication treatment for opioid use disorder? A national study of outpatient specialty treatment settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 126, 108329.