A state policy option to expanding access to methadone: Utilize Federally Qualified Health Centers

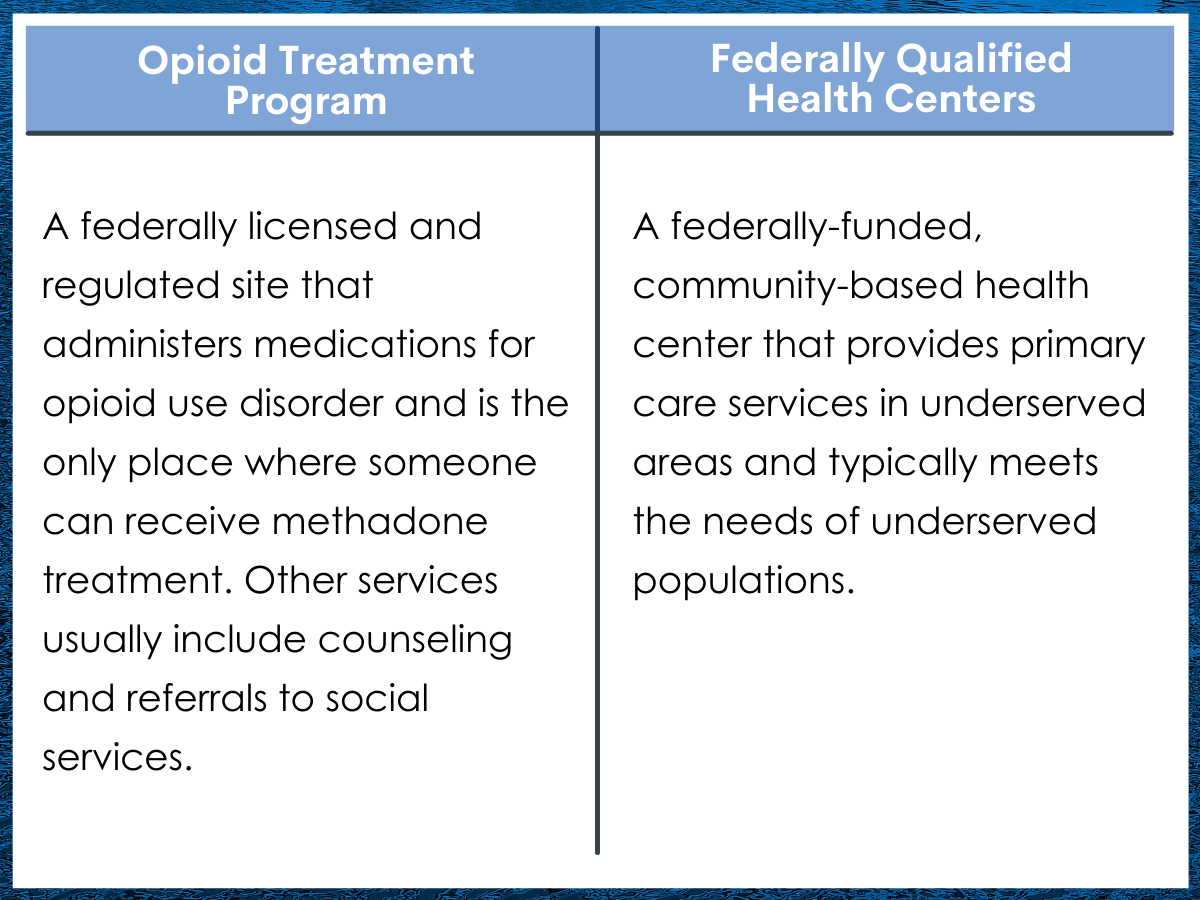

Opioid agonist medications, such as methadone, are an effective treatment option for opioid use disorder. However, they are underutilized as only 20% of individuals with opioid use disorder receive any treatment and only a third of these treated individuals receive opioid use disorder medication. Some of this underutilization is due to access, especially in rural areas. In this study, researchers used an innovative geo-mapping technique to examine whether a recent state policy in Ohio that allows certain facilities – Federally Qualified Health Centers – to dispense methadone, might enhance access by serving as extensions to Opioid Treatment Programs.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine (typically prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), are empirically-supported treatment options that decrease mortality, reduce illicit opioid use, and increase retention in treatment. Methadone in particular has been shown to increase retention in treatment compared with buprenorphine and is considered a preferred treatment option for certain individuals, such as those seeking more structured treatment. Despite this evidence, only 20% of individuals with opioid use disorder in the United States receive any treatment and only a third of these treated individuals receive opioid use disorder medication. Even so, there has been an increase in the number of people prescribed these medications and an increase in facilities that offer this treatment option over the last 12 years. Importantly, however, these services tend to be concentrated in urban areas.

Internationally, there is variation in how opioid use disorder medications are delivered in the treatment system. For example, in the United Kingdom, methadone can be delivered in community-based settings, such as pharmacies. In the United States, methadone is dispensed by regulated and licensed Opioid Treatment Programs, with federal statutes requiring in-person methadone administration six days a week during the first 90 days of treatment. This makes travel a significant barrier to some individuals in accessing methadone treatment and can pose an undue burden in the individual’s quality of life.

There has been advocacy for reforming methadone delivery, such as expanding access through the utilization of alternative settings to administer the medication, which is allowable by federal regulations, though state regulatory restrictions have limited its adoption.

In 2019, Ohio enacted a policy that allowed for alternative settings, such as Federally Qualified Health Centers, prisons, jails, and county health departments, to serve as medication units for Opioid Treatment Programs, though this policy has yet to be implemented. In this study, researchers examined if using Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units would increase coverage of opioid use disorder treatment based on need, and if this coverage was further increased by using a chain pharmacy.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a geospatial modeling analysis of zip codes within Ohio with at least one opioid overdose death in 2017 that examined the proportion of opioid use disorder treatment need that was within a 15-minute and 30-minute drive time of methadone treatment in three different scenarios: existing Opioid Treatment Programs; Opioid Treatment Programs with Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units; and Opioid Treatment Programs with both Federally Qualified Health Centers and a chain pharmacy serving as medication units. Results were broken down by urban-rural classification of the zip codes.

Figure 1.

The primary outcome used in this study was the proportion of opioid use disorder treatment need aggregated by zip code within a 15- or 30-minute drive time of an Opioid Treatment Program or a medication unit extension of the program. The amount of treatment need in each zip code was defined as the total number of opioid overdose deaths. The researchers used this as a proxy for opioid use disorder treatment need because it is a widely used measure of opioid use disorder -related harm and represents the highest priority for interventions to treat opioid use disorder, though nonfatal overdoses were also used as a proxy for opioid use disorder treatment need as part of a sensitivity analysis (an alternative way to specify the model to increase the rigor of the study). The 15- and 30-minute drive times were selected based on prior studies demonstrating that retention in treatment decreases with these travel times. Zip codes were stratified into four levels of urban-rural classification (urban, suburban, large rural, and small rural) based on Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes.

This geospatial model measured coverage of opioid use disorder treatment needs in three different scenarios. First, coverage by existing Opioid Treatment Programs was modelled to establish a baseline for supply of and need for methadone treatment in Ohio. Next, the hypothetical scenario of providing coverage using Federally Qualified Health Centers as a medication unit extension of the Opioid Treatment Programs was modelled in accordance with the new policy enacted by Ohio in 2019. Finally, a chain pharmacy (Walmart) was added to further extend services (although not a part of the Ohio policy), and the combined coverage of the Walmart pharmacies, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and Opioid Treatment Programs was modelled. Service at Opioid Treatment Programs was prioritized over services provided at Federally Qualified Health Centers and the chain pharmacies, such that not all the possible medication units were used to extend Opioid Treatment Programs services. The research team used the Ohio Department of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics to obtain data on overdose deaths, the SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator to identify Opioid Treatment Programs in Ohio, the Health Resources and Services Administration data warehouse to identify Federally Qualified Health Centers in Ohio, and Walmart’s online store finder to identify Walmart pharmacies in Ohio.

There were 4183 opioid overdose deaths in Ohio in 2017 that were associated with zip codes, representing 40% (n = 581) of all the zip codes in the state. Among the included zip codes, 25% were considered rural (either large rural or small rural). Opioid overdose deaths were aggregated at the zip code level and the population weighted center of the zip code was used as the location of the opioid use disorder treatment need and was geocoded (i.e., latitude and longitude coordinates put into a geographic information system software). A total of 22 Opioid Treatment Programs, 145 non-school based Federally Qualified Health Centers, and 145 Walmart pharmacies were successfully geocoded. Once all locations were geocoded, the researchers used the Bing Map Distance Matrix Application Program Interface (API) to calculate drive times based on predictive traffic information.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

One-third of treatment need was outside a 15-minute drive of an existing Opioid Treatment Program, with proportion of treatment need covered decreasing with increasing rural classification.

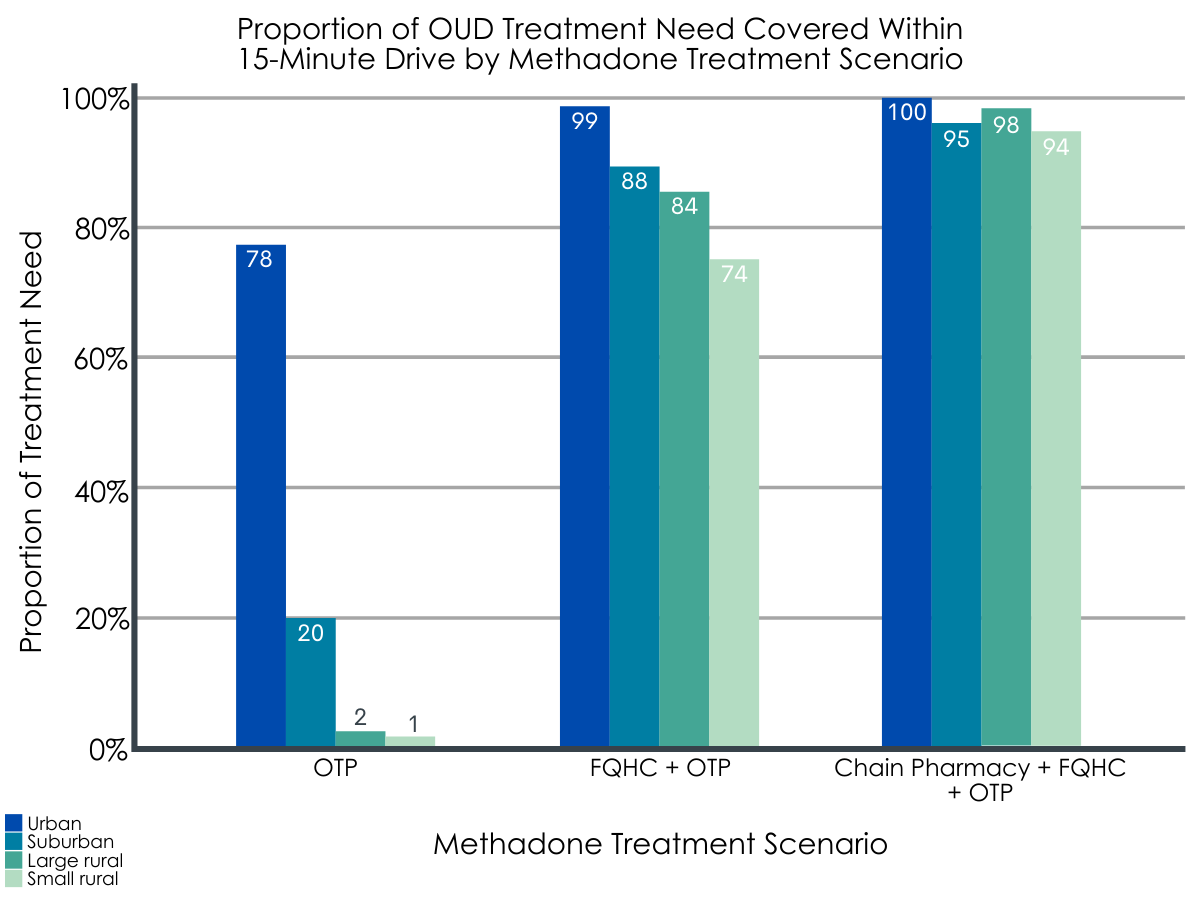

Among zip codes with at least one opioid overdose death, 64% of treatment need was within a 15-minute drive time of an Opioid Treatment Program and 81% was within a 30-minute drive. This proportion differed by urban-rural designation, with 78% of treatment need within a 15-minute drive of an Opioid Treatment Program in urban areas, 20% in suburban areas, 2% in large rural areas, and 1% in small rural areas.

The proportion of treatment need within a 15-minute drive of an Opioid Treatment Program significantly increased when Federally Qualified Health Centers were added as medication units.

With the addition of Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units, the proportion of treatment need within a 15-minute drive to an Opioid Treatment Program or Federally Qualified Health Centers was 96% and 100% was within a 30-minute drive. This proportion differed by urban-rural strata, with 99% of treatment need within a 15-minute drive of an Opioid Treatment Program or Federally Qualified Health Centers in urban areas, 88% in suburban areas, 84% in large rural areas, and 74% in small rural areas.

The proportion of treatment need covered further increased when Walmart pharmacies were included as medication units.

With the addition of both Federally Qualified Health Centers and Walmart pharmacies as medication units, the proportion of treatment need within a 15-minute drive to an Opioid Treatment Program or medication unit was 99% and 100%. This proportion differed by urban-rural strata, with 100% of treatment need within a 15-minute drive of an Opioid Treatment Program or medication unit in urban areas, 95% in suburban areas, 98% in large rural areas, and 94% in small rural areas.

Figure 2. OTP = Opioid Treatment Program; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this geospatial modeling analysis done in Ohio, more than a third of opioid use disorder treatment need was outside a 15-minute drive time of an Opioid Treatment Program to access methadone treatment, with coverage further limited among those in rural areas. Critically, this gap was significantly mitigated by adding Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units for Opioid Treatment Program, especially in rural areas.

Findings from this study demonstrate that fully implementing the new Ohio policy would significantly increase access to methadone treatment for those with an opioid use disorder treatment need, especially in rural areas. Most individuals with opioid use disorder do not receive empirically-supported treatment in the United States. This treatment gap is widened in rural areas, where many regions have been designated as “methadone deserts” and the few Opioid Treatment Programs that provide services may have long waiting lists. Although including a chain pharmacy as a further extension of Opioid Treatment Program services only resulted in modest expansion of methadone treatment coverage, this option may be warranted to ensure that all people with opioid use disorders have access to this treatment option, especially those that have limited transportation choices or live in the most isolated communities.

Given that overdose deaths continue to rise in the United States, there has been a call for reform of methadone treatment, aligning the delivery system with those used internationally that safely expand access. In the model encouraged by the new Ohio policy, patients could receive supervised daily doses of methadone at Federally Qualified Health Centers, although an initial evaluation and counseling sessions would still have to be done at an Opioid Treatment Program. Building off of successful adaptions made during the COVID-19 pandemic, counseling sessions could be provided through a telehealth platform and take-home doses could be increased for clinically stable patients. These changes would be especially impactful in rural areas. For those that still face transportation barriers, mobile methadone administration units could be considered, where methadone is transported directly to patients.

Study findings show that rural areas are the most underserved in terms of accessibility to methadone treatment for those who need it. However, when Federally Qualified Health Centers were added as medication units, the greatest absolute increase in coverage of treatment need was in urban areas. In other words, even though access in urban areas was better than rural areas, higher populations in urban areas led to a significant increase in coverage of opioid use disorder treatment need.

Policymakers should not overlook the spillover effects of enacting a statewide policy to increase access to methadone treatment in rural areas, as areas with a high density of opioid use disorder treatment need are also likely to benefit. In addition, only 31% of the Federally Qualified Health Centers were used in the geospatial model, as Opioid Treatment Programs took priority over Federally Qualified Health Centers in providing methadone treatment, suggesting that a targeted expansion – where Federally Qualified Health Centers in the most high-need areas could adopt methadone dispensing – would be the most efficient implementation of this policy. This is encouraging as it is unlikely that all Federally Qualified Health Centers will choose to adopt this policy given the need to overcome various implementation barriers.

Although enacting a policy like the one in Ohio is a first step to expanding access to methadone treatment, policymakers and treatment providers may benefit from close consideration of barriers to implementing this policy, such as costs, lack of knowledge among providers, and stigma towards methadone. Implementation interventions to speed adoption are likely needed, such as public messaging to reduce stigma, provider education and workforce development, and financing strategies to ensure reimbursement and sustainability. These barriers are likely to vary across states, along with the existing supply of Opioid Treatment Programs, the treatment need, and the infrastructure that could serve as medication units. In addition to the supply-side barriers of implementing a policy like this, attitudes and preferences of those with opioid use disorder should be considered and a menu of options available along with methadone.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study assumes that all those identified as needing opioid use disorder treatment will utilize methadone. Although it is important for those with opioid use disorder to have access to a menu of options, many will select other treatment modalities, such as buprenorphine, extended-release naltrexone, or residential treatment programs that may not offer medications.

- This study does not take into account additional barriers that may increase driving time, such as lack of transportation, traffic, weather, and construction.

- Opioid overdose deaths were used as a proxy for treatment need which may not perfectly correlate with the prevalence of opioid use disorder in an area. Authors did use nonfatal overdoses in a sensitivity analysis which may better reflect opioid use disorder prevalence. Also, deaths were aggregated per zip code with a population-weighted mean serving as the geocode, which may not represent accurate driving times for some.

- Generalizing these results to other states to inform policy should be done with caution. The gap between supply and treatment need varies by state, as well as the infrastructure that could serve as medication units.

- This study assumes that capacity at Opioid Treatment Programs is unlimited. However, many programs have waiting lists, especially in rural areas.

- The implementation of this policy is likely to experience multiple barriers, including costs, lack of knowledge among providers, and stigma.

BOTTOM LINE

In this geospatial modeling analysis done in Ohio, more than a third of opioid use disorder treatment need – measured by opioid-involved overdose deaths in a given zip code – was not within a 15-minute drive time of an Opioid Treatment Program to access methadone treatment. Coverage of opioid use disorder treatment need decreased with rural classification of zip codes, although this gap was significantly mitigated by adding Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units for Opioid Treatment Programs, especially in rural areas.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Unlike other countries, methadone treatment is highly regulated in the United States, and this regulation has contributed to increased stigma towards methadone and limited access. For many people, opioid use disorder is a chronic, relapsing disorder that may take several treatment attempts to achieve remission and responds best to medication. Methadone is one of two forms of opioid agonist treatment for the disorder that has demonstrated strong evidence of decreasing mortality, reducing illicit opioid use, and increasing retention in treatment. Fortunately, access to these medications has increased in recent years. Through shared decision-making, individuals considering medications for opioid use disorder should discuss all options with their provider so that the medication selected provides the best fit based on individual characteristics and stage of stabilization and recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For many people, opioid use disorder is a chronic, relapsing disorder that may take several treatment attempts to achieve remission and responds best to medication, though a minority of those with the disorder receive medications. Innovative delivery systems and treatment models may help increase access, engagement, and retention for these individuals. The enacted policy in Ohio allows Federally Qualified Health Centers, prisons, jails, and county health departments to serve as medication units for Opioid Treatment Programs. The characteristics of Federally Qualified Health Centers may be particularly advantageous to serve as medication units. However, the initial evaluation and counseling sessions must still take place at the central Opioid Treatment Program. Recent changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, like increased adoption of telehealth for counseling sessions and expanding take-home privileges to clinically stable patients, have the potential to address these issues, along with increasing the autonomy of patients and making treatment more attractive.

- For scientists: Although enacting a policy to expand access to methadone treatment by using Federally Qualified Health Centers as medication units is promising, implementation of this policy would be challenging. If this policy were to be implemented, studies should explore implementation barriers, especially those related to stigma towards medications for opioid use disorder. These barriers are likely to vary across states, along with the existing supply of Opioid Treatment Programs, the opioid treatment need, and the infrastructure that could serve as medication units. Adoption of the policy itself may differ based on a state’s political and economic environment. In addition to increasing access, strategies to increase retention are particularly salient for those in medication treatment. Recent changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, like increased adoption of telehealth for counseling sessions and expanding take-home privileges to clinically stable patients, have the potential to increase the autonomy of patients and make treatment more attractive. Studies should evaluate the safety and impact of this temporary lax in regulations.

- For policy makers: As overdose deaths continue to increase in the United States and the majority of those with opioid use disorder do not receive evidence-based medication treatment, which has been shown to substantially reduce opioid-related mortality, innovative policies are needed. One option may be state policies that expand access to medications for opioid use disorder, such as the recent Ohio policy that allows Federally Qualified Health Centers, prisons, jails, and county health departments to serve as medication units for Opioid Treatment Programs, which would especially impact rural areas. Internationally, the delivery system for methadone is more flexible and utilizes primary care and pharmacies. Aligning the U.S. delivery system to these international systems would expand the accessibility of methadone and buprenorphine (often prescribed in formulation with naloxone, known by the brand name Suboxone) to those with opioid use disorder. Implementation interventions to address costs, lack of provider knowledge, and stigma towards medication for opioid use disorder may be needed to increase adoption after these types of policies are enacted. These barriers are likely to vary across states, along with the existing supply of Opioid Treatment Programs, the treatment need, and the infrastructure that could serve as medication units.

CITATIONS

Iloglu, S., Joudrey, P. J., Wang, E. A., Thornhill, T. A. IV, & Gonsalves, G. (2021). Expanding access to methadone treatment in Ohio through federally qualified health centers and a chain pharmacy: A geospatial modeling analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 220, 108534. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108534