What are the factors that influence public support for removing barriers to recovery capital for those with felony drug convictions?

Individuals with felony drug convictions face public stigma and significant policy barriers in improving their social determinants of health, such as restrictions on housing and employment (also known as recovery capital). These barriers can hinder the wellbeing of these individuals and their families, in addition to widening and perpetuating the disparities already caused by mass incarceration. In this study, authors show how societal stigma and public support for less punitive policy restrictions changed based on how the consequences of substance use and incarceration are framed.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Individuals with a history of incarceration are highly stigmatized, and substance use disorder is one of the most stigmatized conditions in the world. Thus, individuals with a felony drug conviction are likely to experience the ‘double stigma’ of having both criminal justice involvement and potential substance use. This stigma has translated into punitive policies, including mandatory minimum sentencing, restrictions on the accessibility of public benefit programs, and criminal justice screening prior to the hiring process for employment. For many, these policies directly impact the wellbeing of individuals with felony drug convictions and their families.

The social determinants of health, such as housing, employment, social support, and food security, are essential to improving health outcomes. In fact, social and economic factors have been suggested to be the most important contributor to health outcomes, more so than health behaviors and clinical care. Those with a history of incarceration have higher morbidity and mortality than the general population. Thus, policies and interventions that improve social determinants of health among formerly incarcerated individuals are likely to reduce their elevated risks for disability and death.

One plausible way to improve health outcomes in those with felony drug convictions is to increase public support for reducing or removing policy restrictions that serve as barriers to improving social determinants of health. In this study, Bandara and colleagues used a vignette-based randomized experiment to investigate whether societal stigma and public support for punitive policies would decrease based on the framing of consequences of substance use and incarceration. These findings could inform how public messaging campaigns might increase support for policy reform and interventions that improve social determinants of health among those with felony drug convictions.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

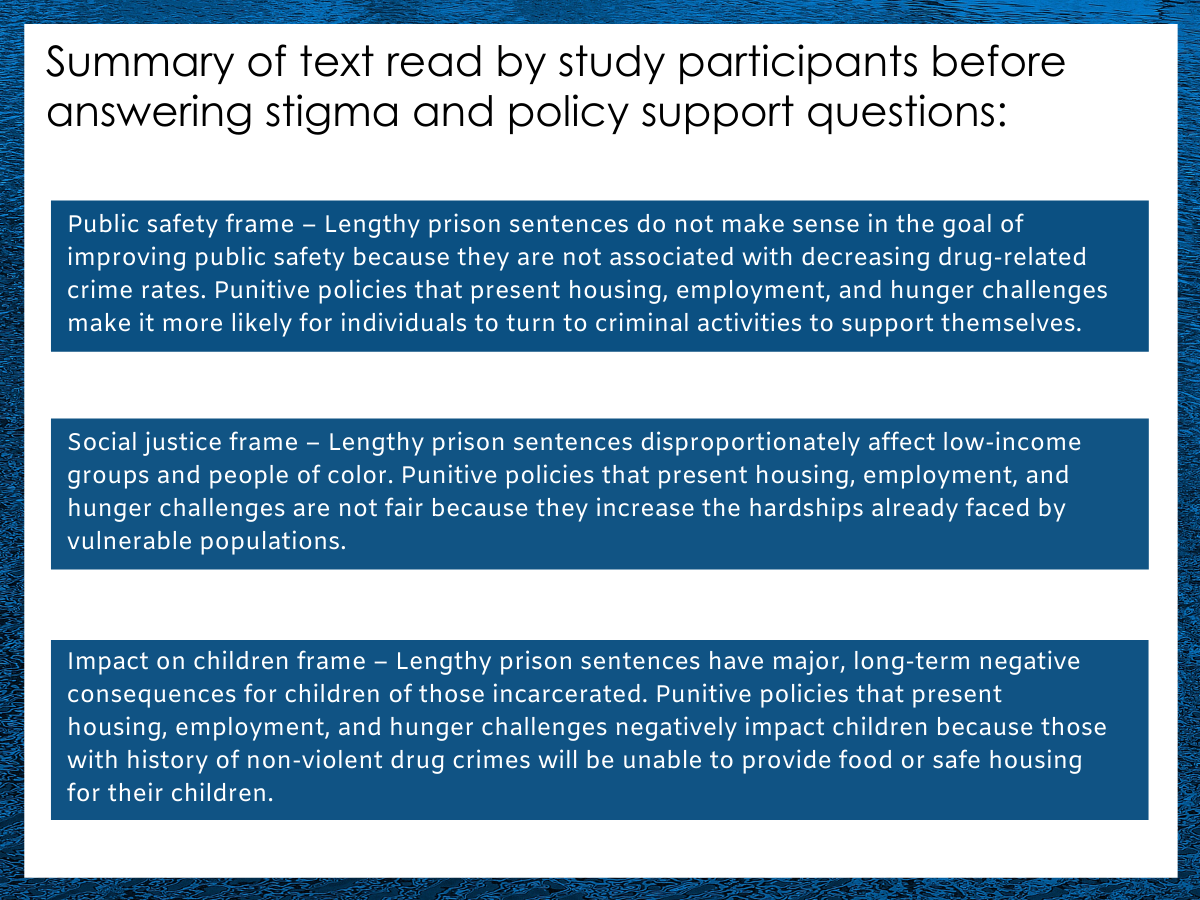

This study used a randomized experimental design where individuals recruited from a representative sample of U.S. adults were assigned into ten different groups, where they did not read a vignette (i.e., control group) or read one of nine vignettes with three different consequence frames either with or without both a sympathetic narrative and image of an individual. Then, study participants were asked questions that measured stigma and support of punitive policies. The consequence frames included: public safety, social justice, and impact on children. The sympathetic narrative was told from the perspective of a father whose son is in recovery from an opioid use disorder and was recently released from prison following a felony drug conviction. The image of the individual associated with the narrative that was presented to the study participants was either a white or black male.

Figure 1.

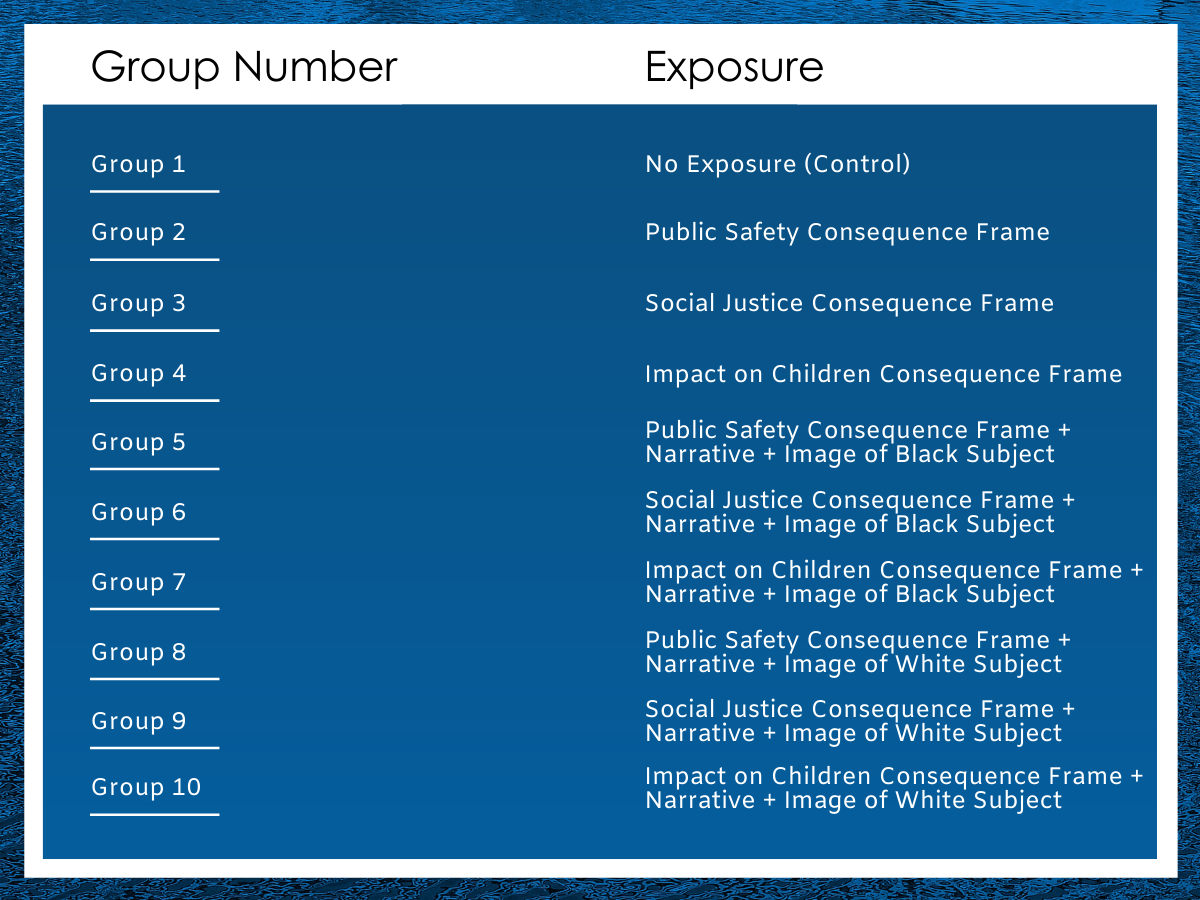

Study participants were randomly drawn from 25,000 households in April 2018 using a probability-based sample of the United States. What this means is that study results will be nationally representative of the entire population. The response rate was 52% for the experiment, resulting in a sample of 3,758 individuals. More than 1,000 individuals were not exposed to a consequence frame and were only asked questions about stigma and policy support, in order to establish a baseline for comparison. Around 300 individuals were randomized to the other nine arms of the experiment as seen below:

Figure 2.

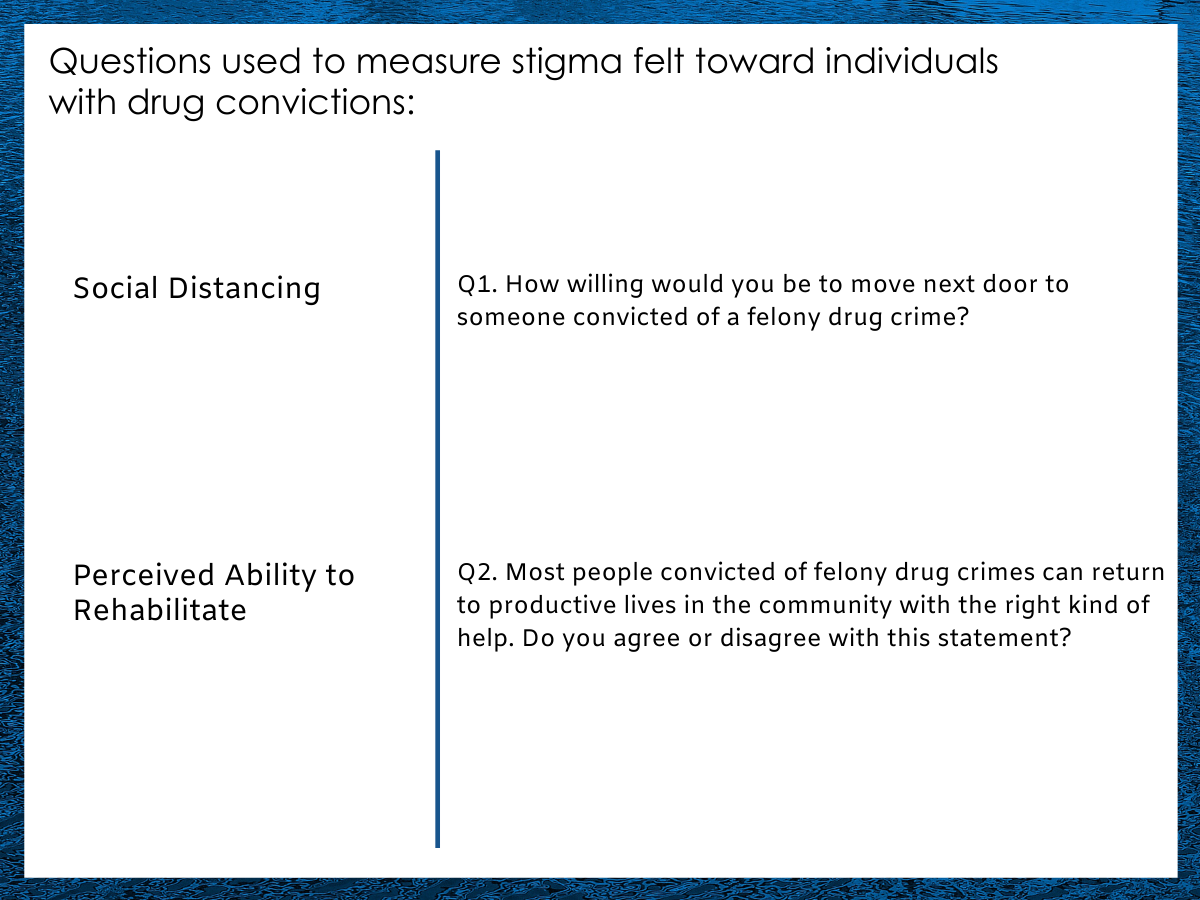

There were two items to measure stigma towards individuals with a felony drug conviction: a measure of social distancing and a measure of perceived ability to rehabilitate.

Figure 3.

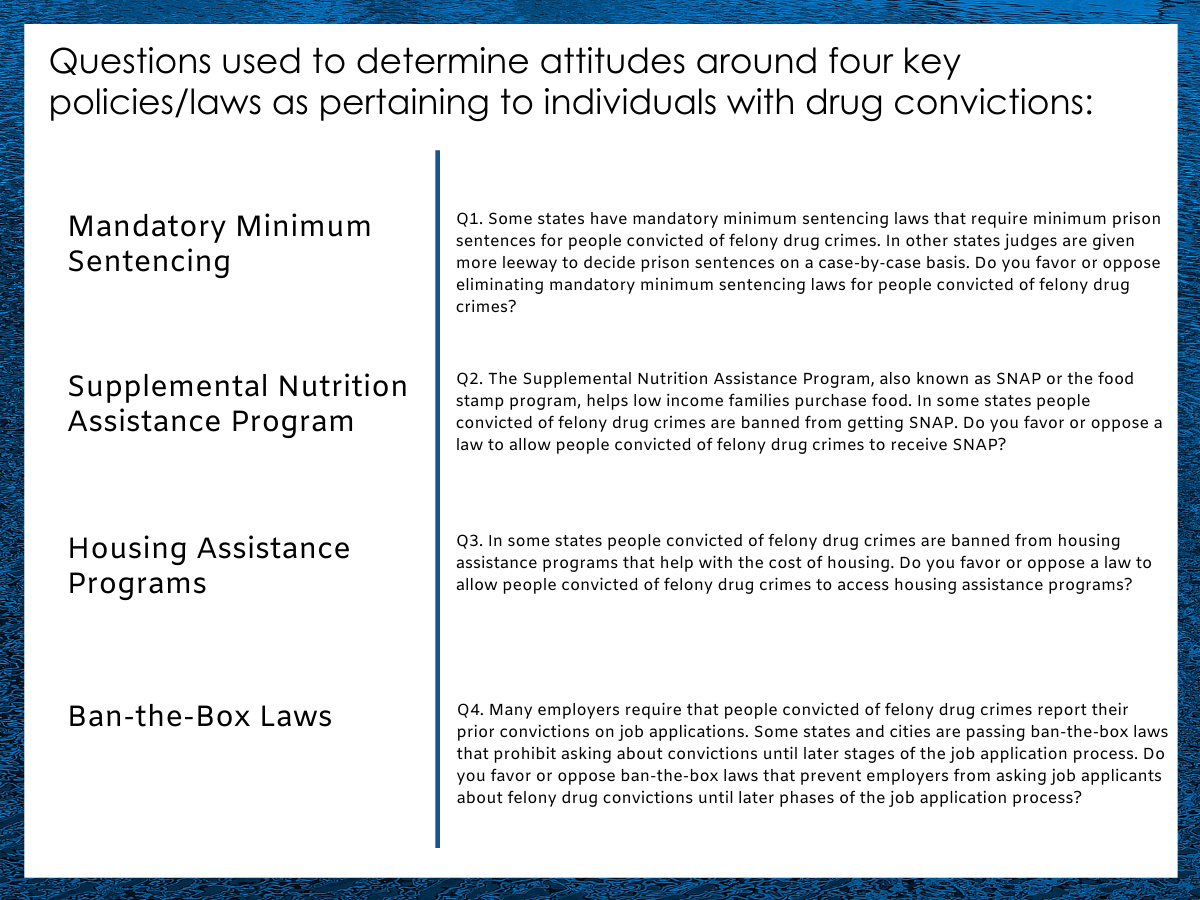

There were four items to measure support for four different policies. Study participants were given one sentence that briefly described the policy followed by asking if they favored or opposed the policy.

While all outcomes were measured on a five-point scale, authors transformed each of these into a dichotomous variable, meaning all study participants either supported or opposed the policies, were or were not willing to move next door to an individual with a felony drug conviction, and did or did not believe in the ability of that individual to return to a productive life after incarceration.

Figure 4.

Baseline national attitudes (without consequence frames) were calculated for stigma and policy support. Authors measured the effect of adding different consequence frames compared to attitudes without any framing. They also examined whether adding a narrative and an image to these frames impacted the attitude and policy support outcomes. In their analysis, authors did not adjust for any sample demographic characteristics (a statistical technique to make the groups more similar so that any difference could be better attributed to differences in the vignettes) because demographics were comparable across all the groups and closely represented the United States adult population.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Stigma was high and support for less punitive policies was low at baseline.

For the group that was asked about the stigma and policy support questions without a consequence frame (the control group), only 29% of respondents were willing to move next door to an individual with a felony drug conviction despite the fact that 72% believed this population could return to productive lives after incarceration. The majority of respondents did not support less punitive policies:

- 45% supported eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing for felony drug crimes.

- 41% supported removing restrictions to SNAP.

- 40% supported removing restrictions on public housing.

- 42% supported enacting employment ban-the-box policies.

The ‘Social Justice’ and ‘Impact on Children’ consequence frame had an impact on stigma.

Participants who read the ‘Social Justice’ (37%) and ‘Impact on Children’ (41%) frames were more likely to be willing to move next door to an individual with a felony drug conviction compared with control participants (29%), though the ‘Social Justice’ frame was associated with participants having lower beliefs (62%) that the individual could return to productive lives after incarceration compared with the control group (72%). There were no significant differences between the ‘Public Safety’ frame and control.

The ‘Social Justice’ and ‘Impact on Children’ consequence frame was associated with support for less punitive policies.

Participants who read the ‘Social Justice’ (55%) and ‘Impact on Children’ (54%) frame were more likely to support ban-the-box policies than the control group (42%). Participants who read the ‘Social Justice’ frame (54%) were more likely to support eliminating mandatory minimums compared with the control group (45%). The ‘Public Safety’ frame was not associated with a change in policy support and there was no effect of the consequence frames on removing restrictions on SNAP and public housing.

The addition of a sympathetic narrative and either an image of a white or black male had marginal effects on stigma and policy support.

Overall, for all participants who read one of the consequence frames, adding a sympathetic narrative had no effect on the stigma or policy support measures compared to reading only a consequence frame (i.e., without an additional sympathetic narrative). Only among participants assigned to the ‘Social Justice’ frame, the additional sympathetic narrative increased respondents’ perceived belief that an individual with a felony drug conviction could lead a productive life (74% with the narrative vs. 62% without the narrative). Within the ‘Public Safety’ frame, the additional sympathetic narrative led to a slight improvement in support for removing public housing restrictions.

When examined across all consequence frames, the race of the young man in the sympathetic narrative – black vs. white — had no effect on stigma or public support. However, within the ‘Social Justice’ frame, if the individual in the sympathetic narrative was White, it elicited greater perceptions for rehabilitation (79% vs. 70%) and more support for removing restrictions to SNAP (55% vs. 43%) than if the individual in the narrative was black.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study showed that individuals with felony drug convictions are a highly stigmatized population which is likely translating into lower public support for less punitive policies that could improve social determinants of health among this population. Employing a ‘Social Justice’ or ‘Impact on Children’ consequence frame may aid campaigns and policy advocacy efforts aimed at reducing this stigma.

Message framing is an important strategy for influencing the perceived agency of individuals with substance use disorders as well as to garner public support for criminal justice reform and controversial evidence-based public health interventions. Findings from this study suggest that highlighting the consequences of an inequitable criminal justice system or the major long-term impact on children of those incarcerated has the potential to reduce stigma and increase support for less punitive policies. In turn, this can improve social determinants of health, such as employment, housing, and food security, for individuals and their families. We know that words matter in describing highly stigmatized conditions like substance use disorders as language has been shown to play an important role in framing how society thinks about substance use and recovery. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary.

Results showing that using a ‘Social Justice’ or ‘Impact on Children’ consequence frame can help reduce stigma and increase support for less punitive policies suggest that contextualizing the life circumstance of individuals with felony drug convictions may be an effective communication strategy. Shifting the consequences of these punitive policies onto the children of individuals who have felony drug convictions may have elicited a more sympathetic response from study participants. Thus, a focus on the ripple effect of a felony drug conviction on other family members may increase the effectiveness of campaigns targeting stigma and policy reform.

Figure 5.

Likewise, shifting the responsibility of an individual’s felony drug conviction onto an unjust system that disproportionately affects marginalized populations may have changed respondents’ beliefs and attitudes. Thus, message framing that highlights the systemic injustices in the criminal justice system may also serve as a communication strategy to reduce stigma and increase support for policy reform aimed at improving social determinants of health. Conversely, this type of framing may come with unintended consequences, as study results suggest that the ‘Social Justice’ frame may also have heightened awareness of the immense challenges that those with felony drug convictions face, decreasing the perception that this population is capability of rehabilitation.

An unsettling finding is that, in the ‘Social Justice’ frame, respondents were more likely to perceive whites with felony drug convictions as able to lead a productive life and more likely to support removing SNAP restrictions for whites compared with blacks. The magnitude of these racial differences was not trivial and indicates a bias based purely on race that warrants further investigation to understand more about what may explain such differential racial attitudes.

Another important finding is that only the ‘Public Safety’ consequence frame with the addition of the narrative had an impact on public support for removing restrictions on public benefit programs and this policy reform was only supported by a minority of respondents in all study groups. This suggests that the public may perceive those with felony drug convictions responsible for the hardships in their lives and unworthy of access to government benefits, except when to deny these individuals access to such programs would be a threat to public safety. These findings highlight that there may be multiple levels of stigma and discrimination affecting formerly incarcerated individuals with felony drug convictions, such as criminal history, substance use, and race.

Of note, the results also show that, regardless of whether consequence frames and sympathetic narratives are used, the majority of the public does not support less punitive policies for individuals with felony drug convictions that would mitigate barriers to improving wellbeing, highlighting persisting obstacles to garnering widespread support for removing restrictions that may improve the social determinants of health in this population. Thus, simply providing evidence framed in the inequitable and widespread consequences of criminal justice involvement for potential substance users is unlikely to sway public opinion to achieve majority support.

More studies testing these critical questions can improve our understanding of people’s beliefs and attitudes toward individuals with felony drug convictions so that communication campaigns and dissemination of evidence-based policy interventions are maximally effective.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Even though authors recruited from a nationally representative sample by tapping into a survey research panel that used probability-based sampling, the random sample chosen from 25,000 households only had a response rate of 52%, and authors did not account for how respondents may have differed from the original, representative sample. Individuals that chose to participate in the experiment may have been very different from those that did not (i.e., more extreme attitudes toward public health policies). We cannot, therefore, assume that these results generalize to the entire population of US adults.

- The sample frame of participants eligible to be picked for this web-based survey covered 97% of households. This means that some households were not eligible to be selected for the survey and other groups of people like those that are homeless, incarcerated, or institutionalized are also not eligible, thus further affecting the national representativeness of this study.

- The sympathetic narrative used in this study portrayed an individual who developed an opioid use disorder after being prescribed opioids as a result of a work-related injury. However, this may not be the pathway to an opioid use disorder for many people. Studies have shown that stigma may be reduced when individuals were depicted as having less control over their initial exposure to opioids.

- The study participants were measured on stigma and policy support after a single exposure to a consequence frame. However, real-world experience would likely consist of multiple exposures from a variety of sources. When study conditions do not accurately reflect conditions in the real world, it is unclear how well these results generalize to real-life situations.

- This is a 10-arm experiment with six outcome measures (the two stigma questions and the four questions on policy support). Therefore, there were many hypotheses tested, and authors did not control statistically for conducting multiple tests at once, increasing the chance that statistically significant findings may have been a result of chance.

- When measuring public support for specific policies, the study participants were only given a brief description of each policy. Participants may not fully understand the implications of maintaining versus changing the policy.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that individuals with felony drug convictions are a highly stigmatized population which is likely translating into lower public support for less punitive policies that could improve social determinants of health among this population. Findings suggest that focusing on racial and economic disparities (a “Social Justice” frame) or on the long-term negative impact on children (an “Impact on Children” frame) may aid campaigns and policy advocacy efforts aimed at this stigma. Framing and language matter: the words family and friends use around substance use can influence what the general public views as potentially effective criminal justice policies and how individuals with a substance use disorder feel they are perceived and supported. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that individuals with felony drug convictions are a highly stigmatized population which is likely translating into lower public support for less punitive policies that could improve social determinants of health among this population. Findings suggest that focusing on racial and economic disparities (a “Social Justice” frame) or on the long-term negative impact on children (an “Impact on Children” frame) may aid campaigns and policy advocacy efforts aimed at this stigma. Patients with both criminal justice involvement and substance use disorders may experience increased stigma beyond what is already a highly stigmatized condition, which could translate into less opportunity to improve social determinants of health. Greater perceived stigma could also make it less likely for individuals with substance use disorder to seek treatment. Factors that support sustained recovery and increased wellbeing, such as gainful employment, stable housing, and food security, could be especially difficult for this population to access. In addition, message framing and the language we use to talk about substance use disorders matters. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary.

- For scientists: This study used a 10-arm randomized experimental design with participants recruited from a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Results revealed that individuals with felony drug convictions are a highly stigmatized population which is likely translating into lower public support for less punitive policies that could improve social determinants of health among this population. Findings suggest that focusing on racial and economic disparities (a “Social Justice” frame) or on the long-term negative impact on children (an “Impact on Children” frame) may aid campaigns and policy advocacy efforts aimed at this stigma. An unintended consequence of the ‘Social Justice’ frame was a decreased perception that those with felony drug convictions are less capable of rehabilitation compared to controls, perhaps through a heightened awareness of the immense challenges that those with felony drug convictions face, although this was attenuated by a sympathetic narrative of a white male compared to a black male. Stigma at the intersection of race, substance use, and criminal justice involvement appears complex, warranting further studies. Even though there are limitations in the generalizability of these results, authors illustrate that message framing may reduce public stigma and increase public support for less punitive policies, which would likely improve social determinants of health in this population. An emerging field of study are the social determinants of health as they relate to sustaining recovery from substance use disorder and decreasing recidivism, which would likely be improved by these less punitive policies. Research at the intersection of politics, the social determinants of health, and substance use is desperately needed to overcome ideological stigma-related barriers that hinder the implementation of evidence-based policy interventions.

- For policy makers: This study showed that individuals with felony drug convictions are a highly stigmatized population which is likely translating into lower public support for less punitive policies that could improve social determinants of health among this population. Findings suggest that focusing on racial and economic disparities (a “Social Justice” frame) or on the long-term negative impact on children (an “Impact on Children” frame) may aid campaigns and policy advocacy efforts aimed at this stigma. If policymakers prioritize research and media campaigns that reduce stigma and support policies that improve the social determinants of health (e.g. gainful employment, stable housing, food security) for those that have a history of incarceration, this may be a more cost-effective option than restrictive, punitive policies that may increase recidivism, negatively impact families, and perpetuate mass incarceration. In addition, message framing and the language we use to talk about substance use disorders matters. For more information on destigmatizing language, please see the RRI’s Addictionary.

CITATIONS

Bandara, S.N., McGinty, E.E., & Barry, C.L. (2020). Message framing to reduce stigma and increase support for policies to improve the wellbeing of people with prior drug convictions. International Journal of Drug Policy, 76, 102643. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102643