Continuing methadone treatment (versus withdrawal) during a prison term produces better one-year post release outcomes

Methadone in the treatment of opioid use disorder is shown to reduce illicit opioid use, injection drug use, and opioid-related overdose death rates. Although methadone treatment during incarceration has the potential to benefit prison populations with opioid use disorder, it is not widely implemented in correctional facilities. Incarcerated individuals taking methadone are often forced to taper off the medication or suffer withdrawal without medical supervision. Therefore, the long-term effects of methadone in this population are not fully understood. The current study showed that for individuals prescribed methadone before they were incarcerated, those who were still taking methadone prior to release had better 12–month outcomes than those not taking methadone.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

A relatively large percentage of incarcerated individuals (23% of state prisoners) report opioid use. Repeated opioid use can lead to tolerance, such that a greater amount of the substance is needed to feel its effects. When opioid use stops, after a while an individual loses the tolerance to the opioid’s effects, and overdose can occur if an individual then begins to use opioids again in amounts similar to those when they stopped. Overdose is of particular concern among inmates with opioid use disorder who return to opioid use after being released from incarceration. Methadone treatment during incarceration is shown to be a helpful way to reduce the risk of overdose and illicit opioid use after incarceration, but it isn’t widely implemented. Incarcerated individuals taking methadone are often forced to taper off the medication or suffer withdrawal without medical supervision. Therefore, the long-term effects of continued methadone treatment in incarcerated populations are not well–defined. In this study, researchers tested the effects of continued methadone treatment versus a forced, but gradual, medically-supervised taper among inmates on several outcomes. These included overdose, substance use, service utilization, and risky behaviors at 12 months after release from incarceration.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The research team conducted a randomized controlled trial between 2011 and 2014. The study sample consisted of 179 individuals incarcerated between 1 week and 6 months at the Rhode Island Department of Corrections. All participants had been enrolled in a methadone treatment program prior to their incarceration. Individuals were randomized to either receive the standard of care (i.e., tapered withdrawal protocol to cease methadone treatment after 1 week of incarceration; n=83) or to receive continued methadone treatment (n=96). Of those who receive the standard of care, 32 individuals were still undergoing the tapered withdrawal protocol at the time of their release and were therefore still receiving methadone. This is because some individuals had shorter jail sentences and they had served the full time of their sentence before they were fully tapered off of methadone. Therefore, the authors conducted separate analyses comparing 1) the randomized groups as assigned (n=83 vs. n=96; i.e., intent-to-treat analysis), and 2) groups based on whether or not an individual was receiving any methadone on the last day of incarceration (n=128 who received methadone vs. n=51 who did not receive methadone; i.e., as-treated analysis). Upon release, all participants were provided linkage to a methadone treatment program in the community, regardless of their assigned condition.

Participants were interviewed 12 months after release. Questionnaires assessed non-fatal overdose (medical examiner reports were used to assess fatal overdose) and emergency department utilization (confirmed via hospital records) in the 12 months since release, as well as substance use and HIV-risk behaviors (transactional sex and injection drug use) in the past 30 days. Re-arrest and re-incarceration were self-reported and confirmed with records from the Rhode Island Department of Corrections. Engagement and continuous enrollment (receiving treatment for >334 days) in methadone treatment were assessed via participant medical records from community methadone treatment programs and additional service use (inpatient, outpatient, 12–step) was evaluated by self-report questionnaire.

Participants had an average age of 33 and the study sample primarily consisted of White (79%) men (78%). Individuals receiving methadone on their final day of incarceration spent fewer days in jail (~30 days) than those who were not receiving methadone (~80 days). Participants receiving the standard of care went an average of 52 days without methadone during incarceration.

Intent-to-treat analysis: Individuals assigned to continue taking prescribed methadone and those assigned to the gradual taper had similar outcomes 12 months after incarceration, including substance use, overdose, service utilization, and risky behaviors.

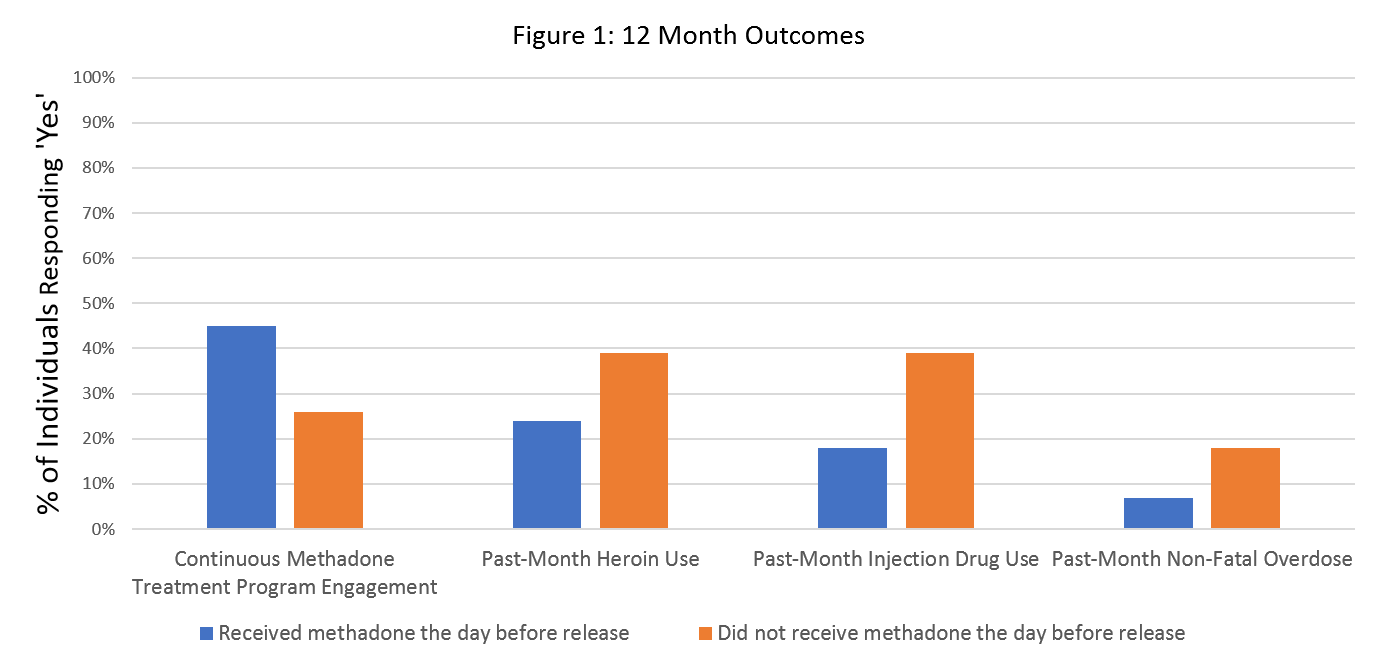

As-treated analysis: Evaluation of groups based on actual methadone treatment (i.e., individuals assigned to the methadone treatment group and individuals assigned to the tapered withdrawal program who had not completely ceased methadone use at the time of release) revealed methadone’s long-term beneficial effects. Relative to individuals who did not receive methadone on the last day of incarceration, individuals who were taking prescribed methadone were less likely to report past-month heroin use, injection drug use, and non-fatal overdose, and were more likely to report continuous engagement in a methadone treatment program over the 12-month study period. Figure 1 below illustrates these effects.

Figure 1.

The groups had similar rates of past-month use of non-heroin substances and rates of re-arrest and re-incarceration in the 12 months following release. Those who received methadone and those who did not receive methadone also had similar rates of 12-step program, residential/outpatient treatment, detoxification, pharmacotherapy, and emergency department service use at any time during the past 12 months.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study suggests that providing ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration may have long-term positive effects up to 12 months post–release to the community. Individuals enrolled in methadone treatment, who continued to receive methadone during incarceration, exhibited lower rates of non-fatal overdose, heroin use, and injection drug use. Consistent with the outcomes of this study, methadone treatment itself is associated with reductions in illicit opioid use, injection drug use, and overdose death rates. Conflicting with previous research, continued methadone treatment did not have an effect on re-arrest or re-incarceration. However, incarceration and arrest are heavily influenced by state/local policies. Therefore, methadone treatment during incarceration may have the potential to reduce recidivism outside of Rhode Island.

Importantly, all participants were receiving methadone treatment prior to incarceration and were provided linkage to a community methadone treatment program upon release. However, notably, individuals who discontinued methadone treatment during incarceration were less likely to report continued engagement in a methadone treatment program post–release. A minimum of 12 months of continuous methadone treatment is advised for optimal recovery outcomes. Therefore, if tapered withdrawal/detoxification during incarceration decreases the likelihood of continued methadone treatment after release, despite linkages to methadone treatment programs, individuals may not reap the maximum benefits of their pharmacotherapy and may be at increased risk for engaging in dangerous substance use behaviors and overdosing following release.

Although the intent-to-treat analysis failed to reveal any long-term effects of methadone, a proportion of the individuals assigned to the tapered withdrawal condition did not reach the end of the taper protocol, and thus were still receiving methadone prior to release. The as-treated analysis compared those who were fully tapered off of methadone prior to their release, relative to those who received continuous methadone throughout incarceration regardless of group assignment. Comparison of these groups demonstrated the long-term beneficial effects of methadone, regardless of fluctuations in dose (maintained, increased, or decreased during incarceration).

Most critically, the past-month (non-fatal) overdose rate at 12-months post-discharge was almost 1 in 5 in the group not receiving methadone, compared to only 1 in 13 in the methadone continuation group. Put another way, the overdose risk for the group tapered off of methadone was 157% higher than those inmates continuing to take it.

Importantly, these benefits require further study. This is in part because, although all participants were receiving methadone treatment prior to incarceration and therefore likely had severe opioid use disorder, the as-treated analysis may have resulted in a more severe population of individuals in the tapered withdrawal condition. Those individuals assigned to the taper condition who did not fully taper prior to release likely had shorter jail sentences and therefore, may have been a less severe criminal justice population. Including these individuals in the methadone group for the as-treated analysis could have ultimately contributed to better outcomes among the methadone group. Therefore, additional research is needed to identify the long-term effects of methadone, independent of criminal justice severity. Nonetheless, studies looking at the short-term effects of continued methadone treatment clearly show its benefits during incarceration. Introducing inmates to opioid use disorder medication (starting inmates on medication for the first time) during incarceration and providing ongoing care up-to release is also shown to benefit inmate outcomes (e.g., lower rates of relapse and re-incarceration).

Despite the demonstrated benefits of ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration, many jails and prisons do not allow individuals the opportunity to continue opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy – detoxification protocols are standard care.

By showing the long-term positive effects of providing inmates with continued access to methadone during incarceration, this study extends the current literature and provides important information for guiding evidence-based policies in the context of correctional facilities.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Duration of incarceration varied among inmates and, as a result, some of the participants assigned to the standard care group were not fully tapered off of their methadone prior to release. Given that some correctional facilities do not follow a taper protocol and instead abruptly stop methadone treatment upon incarceration, studies are needed in these environments to determine if the tapering protocol masked or reduced the effects of continued methadone treatment.

- This study was conducted in Rhode Island and the majority of participants were White men. Additional research is needed to determine if these outcomes extend to inmate populations in other states and with different demographics.

- Inmates in this study had prison sentences of 6 months or less. Furthermore, sentence duration differed between those who fully tapered off of methadone and those who continued to receive methadone. Additional research, controlling for sentence duration and assessing populations with longer sentences, is needed.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study suggests that ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration may help individuals to avoid overdose, illicit opioid and injection drug use, and to continue engagement in a methadone treatment program up to 12months after release into the community. Therefore, individuals receiving methadone prior to incarceration might benefit from a correctional facility with policies that support ongoing methadone treatment while serving a sentence. At present, some jails and prisons do not allow individuals to continue medication treatment for opioid use disorder during incarceration. By showing the long-term positive effects of providing inmates with continued access to methadone, this study provides important information that can ultimately guide effective changes in correctional facility policies that support opioid use disorder recovery and lower rates of opioid-related overdose.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study suggests that ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration may help reduce rates of overdose, illicit opioid use, and injection drug use as far out as 12 months post–release into the community. Ongoing treatment during incarceration may also encourage continued engagement in a methadone treatment program over the year following release, permitting the continued care necessary for optimal recovery outcomes. At present, some jails and prisons do not allow individuals to continue pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during incarceration. Studies like this demonstrate the long-term positive effects of continued substance use disorder treatment in correctional facilities and inform the policy changes needed to support long-term recovery among opioid use disorder patients.

- For scientists: This study suggests that ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration may help individuals to avoid overdose, illicit opioid and injection drug use, and to continue engagement in a methadone treatment program up to 12 months after release into the community. Investigation was limited to prison sentences of 6 months or less in the state of Rhode Island and detoxification procedures among the control group did not permit full discontinuation of methadone among all participants prior to release. Additional research is needed to determine if the tapering protocol masked or reduced the effects of continued methadone treatment and to replicate these findings in prison populations with varying demographics. By showing the long-term positive effects of continued opioid agonist treatment during incarceration, research can continue to guide the development of new evidence-based policies.

- For policy makers: This study suggests that ongoing methadone treatment during incarceration may help reduce rates of overdose, illicit opioid use, and injection drug use up to 12 months after release into the community. Ongoing treatment during incarceration may also increase continue engagement in a methadone treatment program, which permits the continued care needed for optimal recovery outcomes. At present, some jails and prisons do not allow individuals to continue pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder during incarceration. Policy reforms are needed to permit ongoing methadone (and Suboxone) treatment in correctional facilities among those inmates undergoing pharmacotherapy at the time of incarceration. Policies that permit the ongoing use of methadone during prison terms may ultimately help address the opioid epidemic by reducing rates of opioid misuse, injection drug use, and overdose on release. By showing the long-term positive effects of continued methadone access during incarceration, this study provides important information for guiding effective evidence-based policy changes to aid the national response to the opioid epidemic.

CITATIONS

Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., McKenzie, M., Macmadu, A., Larney, S., Zaller, N., Dauria, E., & Rich, J. (2018). A randomized, open label trial of methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal in a combined US prison and jail: Findings at 12 months post-release. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 184, 57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.023