What do inmates think about their prison-based opioid use disorder medication programs? Some perceived benefits and areas for improvement

Opioids are involved in 68% of all drug overdose deaths. Medications for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone, Suboxone, Vivitrol) are shown to reduce illicit opioid use, risky behaviors, and opioid-related overdose death rates. These medications may be particularly beneficial in correctional settings because inmate populations with opioid use disorder are at increased risk of overdose after being released from incarceration. To help guide program development in other correctional facilities, this study characterized the benefits and challenges experienced by incarcerated individuals who participated in Rhode Island’s state-wide inmate pharmacotherapy program.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Drug overdose is the leading cause of injury-related death in the United States. Rising overdose death rates are largely attributable to opioids, which were involved in 68% of the 70,000 drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2017.

The risk of opioid-related overdose is particularly high among inmate populations with opioid use disorder after being released from incarceration. This is because repeated opioid use can lead to opioid tolerance and the need for greater amounts of the substance to feel its effects. When incarcerated, individuals stop opioid use and, as a result, the tolerance to opioid’s effects is lost. If an individual is released from incarceration and starts to use opioids again in amounts similar to those when they stopped, overdose can occur because of a loss of tolerance.

Despite this increased risk of opioid-related overdose, resistance toward medication treatment in criminal justice settings continues to be an issue, and few jails and prisons have yet to implement medication treatment programs in the United States. Recognizing this increased overdose risk in inmate populations, the Rhode Island department of corrections was the first to implement a statewide program that provides access to all FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine-based formulations like Suboxone, and naltrexone-based formulations like Vivitrol) in criminal justice settings. This program was shown to decrease overdose death rates after incarceration, but few other U.S. jails and prisons have implemented comprehensive opioid use disorder medication programs like it. In an effort to further characterize the program’s benefits and guide the implementation of opioid use disorder programs in other correctional facilities, this study assessed the perceived benefits and challenges experienced by inmates participating in the Rhode Island pharmacotherapy program.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In this qualitative study, the authors conducted one-hour-long semi-structured interviews with forty inmates participating in the Rhode Island Department of Corrections opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy program. As part of the state-wide program, inmates diagnosed with opioid use disorder either initiated or continued the medication treatment of their preference at intake. Medications included (1) methadone, (2) buprenorphine – often prescribed with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone, and (3) naltrexone – often administered in its extended release form via injection (i.e. depot formulation) and known by the brand name Vivitrol. In addition to medication, inmates regularly attended group counseling sessions and received linkages to community pharmacotherapy programs in the community upon release. Qualitative interviews were conducted among 40 of the program’s patients and addressed participants’ attitudes toward opioid use disorder medications, experiences with medication treatment while incarcerated, perceived benefits/challenges of the program, substance use plans after release, and beliefs about fentanyl (an opioid for which misuse is associated with particularly high rates of overdose). Interviews were recorded and then coded by three researchers to identify trends in responses according to the study topics of interest.

Consistent with the broader population of inmates participating in Rhode Island’s medication program, 50% of this study’s participants were undergoing methadone treatment, 48% received buprenorphine treatment, and 2% received depot naltrexone. Half of the participants had initiated their pharmacotherapy before being arrested and the other half started medication during incarceration. Participants were predominantly white (83%) heterosexual (88%) men (70%), with a high-school education or greater (80%) and an average age of 37 years. Prior to incarceration, the majority of participants were using heroin (95%) and/or non-medical prescription opioids (75%), followed by cannabis (53%), benzodiazepines (30%), and alcohol (20%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Participants reported largely positive experiences with the medication program. Perceived benefits of the program included:

- Prevented experiences of withdrawal during incarceration

- Decreased presence of illicit substances in the correctional facilities

- Improved overall environment at correctional facilities

- Fewer inmates feeling ill from withdrawal

- Less drug-related violence and enhanced feelings of safety

- Reduced staff burden

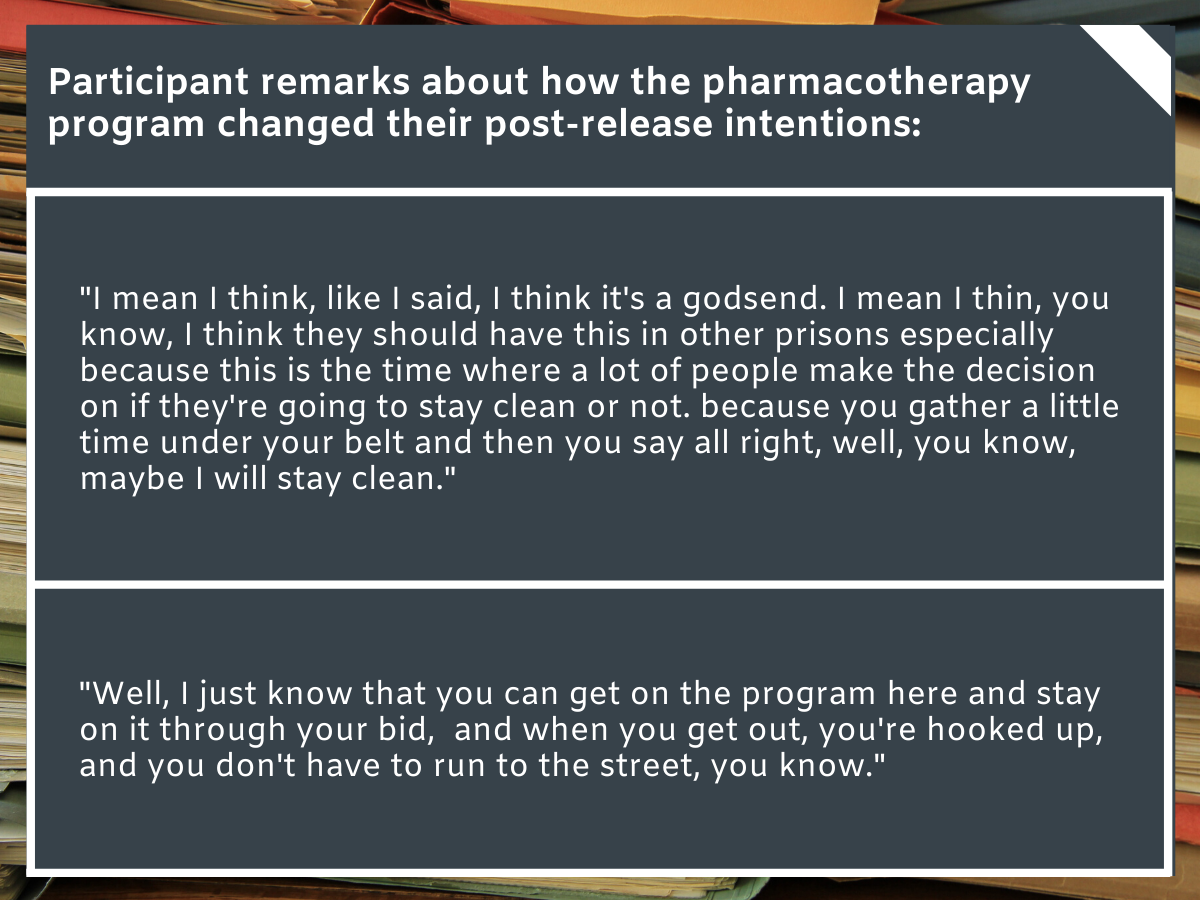

- Promoted healthy post-incarceration intentions

- Plans to continue pharmacotherapy

- Plans to refrain from substance misuse

Figure 1.

Participants also reported a number of ways to improve the program. Perceived challenges and suggestions for improving the pharmacotherapy program included:

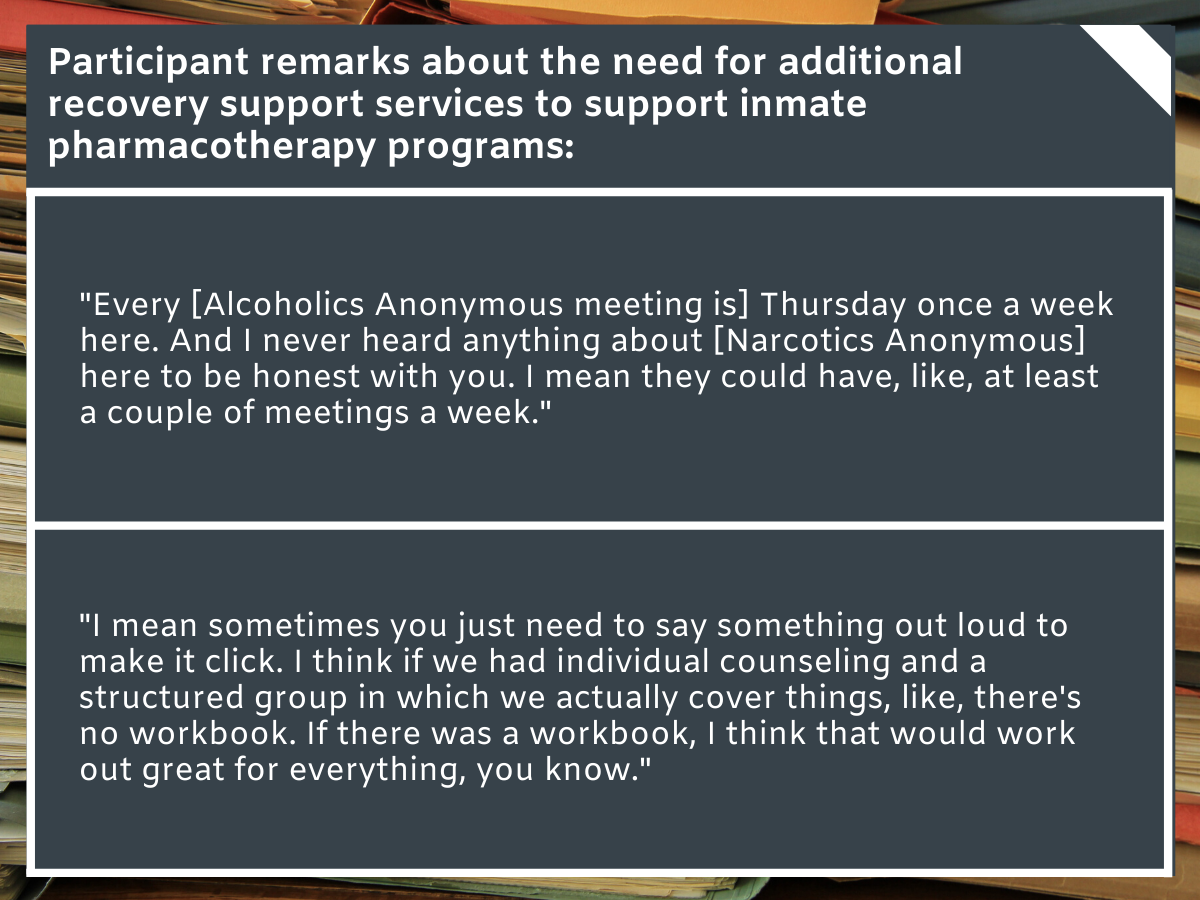

- Limited range of recovery support services offered at correctional facilities

- Need for a broader range of mutual help services (e.g., offering Narcotics Anonymous in addition to Alcoholics Anonymous

- Need for individualized counseling and structured group meetings

- Limited knowledge of addiction and medications among correctional facility staff

- Some staff were perceived as being outwardly opposed to medications or misinterpreting it as a way to ‘get high’

- Led inmates to feel stigmatized

- Some staff were perceived as being outwardly opposed to medications or misinterpreting it as a way to ‘get high’

- Anxiety and uncertainty about obtaining linkage to care and transitioning to community-based medication programs after release

- Need for inmate education about the transition process prior to discharge

- Demand for additional resources (e.g., contact information for community-based medication programs, discharge planner provided at intake) to help inmates plan their own transitions if needed

- Some participants reported extended wait times to receive their first dose of medication at correctional facilities

- Some delays among new medication patients

- Caused withdrawal

- Diminished patients’ perceptions of the medication’s benefits

- Delays among prior medication patients seeking to continue their treatment during incarceration

- Due to lack of coordination between community providers and the department of corrections (e.g., obtaining medication records)

- Some delays among new medication patients

Figure 2.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

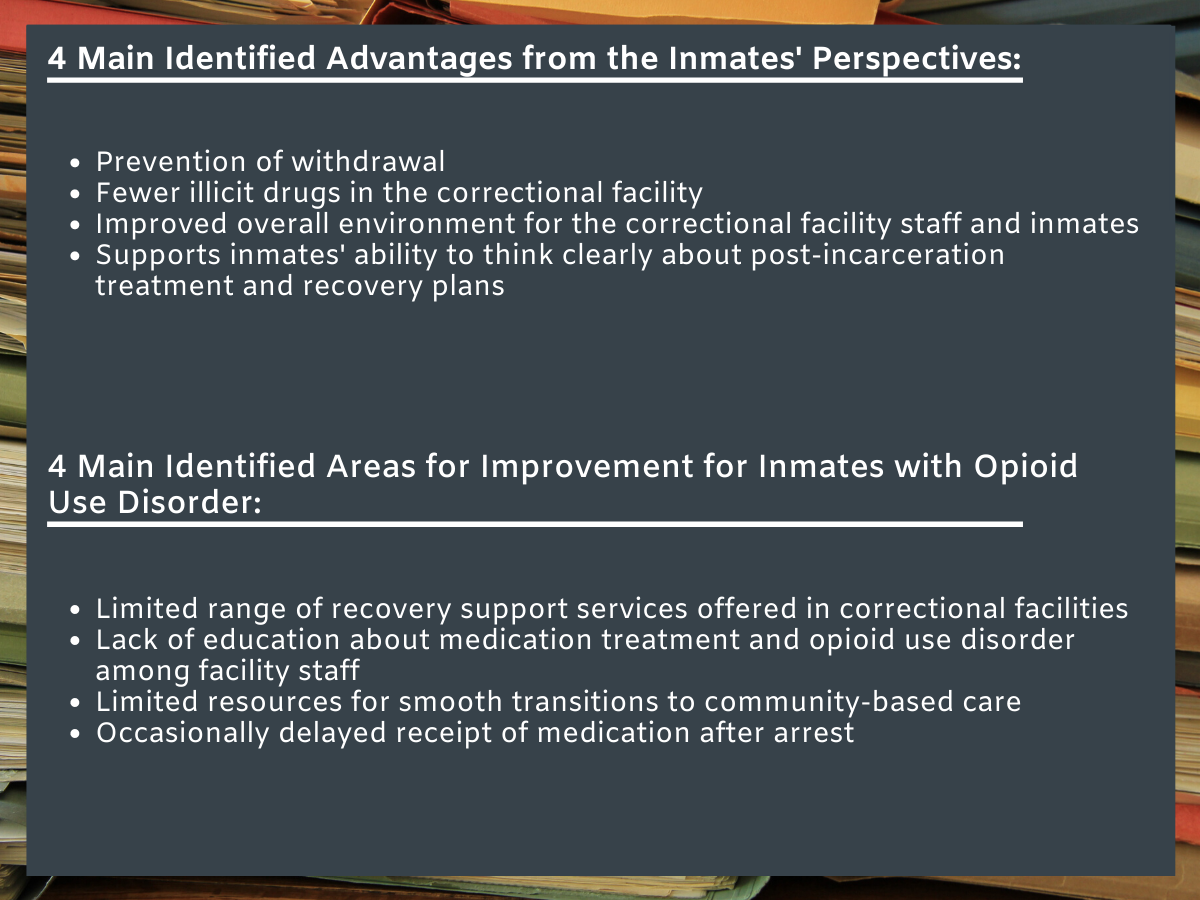

This study found generally positive experiences among inmates participating in the Rhode Island Department of Corrections opioid use disorder medication program, highlighting the feasibility and patient acceptance of comprehensive medication treatment programs in correctional facilities. As expected, one of the reported benefits of the program was management of withdrawal symptoms.

Figure 3.

Medications like methadone and buprenorphine alleviate withdrawal symptoms and craving without producing the euphoria associated with short acting opioid (e.g., heroin) misuse. By reducing illness and discomfort associated with withdrawal, medications might allow inmates to focus on post-incarceration plans for bettering their lives, which could ultimately reduce rates of recidivism.

The program also helped inmates feel more capable of refraining from substance use and continuing treatment after being released from incarceration. Indeed, previous studies show that initiating pharmacotherapy in correctional settings can promote recovery-focused behaviors after being released from incarceration, including continued medication receipt as far out as one year post release.

Inmates believed that the medication program reduced the prevalence of illicit substances circulating within the correctional facility. This finding requires additional research, as perceptions could be due to an actual decrease in the demand and supply of illicit substances or diminished attention toward illicit substances among patients as a result of managing withdrawal/craving.

Inmates thought the program enhanced the prison/jail environment for staff and other inmates. By reducing illicit substance use and experiences of withdrawal in the correctional facility, staff were thought to be less burdened and drug/withdrawal facilitated violence was perceived as less prominent. Therefore, the program’s benefits might extend beyond the patient population to enhance feelings of safety and reduce staff workload.

In addition to noting the benefits of the state-wide program, many had suggestions for improving it. More specifically, many inmates noted a need to educate correctional-facility staff about addiction and pharmacotherapy, and to offer a broader range of recovery services. Though additional research is needed to identify optimal interventions for minimizing stigma among stakeholders, providing staff with a basic understanding of addiction/medications could help to minimize negative attitudes toward medication treatment and inmates who seek it, and could possibly help reduce perceived experiences of stigma among inmates. Furthermore, offering a broader range of recovery services might ultimately facilitate treatment and recovery.

While more research is needed, initial studies suggest mutual help (e.g., narcotics anonymous, alcoholics anonymous, SMART recovery) participation is associated with better outcomes among individuals taking buprenorphine over and above their adherence to the medication. Inmates in this study noted that facilities offered a limited range of recovery services (e.g., only offering alcoholics anonymous) and wished additional services were available. Offering a variety of services in correctional facilities would allow inmates an opportunity to identify the services they like and benefit from most, and incorporate these services into their post-release plans.

Some participants communicated uncertainty around the process of transitioning from the correctional facility’s pharmacotherapy program to a community-based program. It may be helpful to work with inmates on the transition process at earlier stages of incarceration, providing them with resources to spearhead their own transition to community care, and scheduling their first appointment to facilitate patient planning and continued treatment in the community, and prevent opioid misuse and related overdose deaths post incarceration.

Although the majority of inmates reported timely receipt of medication, some patients noted delayed treatment in the correctional facility. Based on this study’s findings, ensuring timely medication treatment might help individuals to reap the full benefits of pharmacotherapy. Developing a set of regulations that ensures coordination between community providers and the department of corrections might also help facilitate medication receipt among pharmacotherapy patients wishing to continue treatment post arrest.

Given the increased risk of opioid-related overdose in inmate populations, and the demonstrated ability of comprehensive medication programs in criminal justice settings to reduce overdose rates, detailed characterization of such programs is essential for adopting and implementing them more broadly.

By documenting inmate perspectives on the program, this study provides important information for developing successful medication programs in additional correctional facilities.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This is a qualitative study and, although qualitative research provides a deeper understanding of phenomena in a naturalistic setting, it lacks statistical representation and does not speak to causal effects. Furthermore, interviews were only conducted with 40 inmates. Although the researchers made an effort to ensure this sample was representative of the broader population of Rhode Island program participants, additional research is needed to confirm the generalizability of these results.

- This study was conducted in Rhode Island and the majority of participants were white heterosexual men. More research is needed to determine if these inmate perceptions would extend to incarcerated populations in other states and with different demographics.

- The majority of participants received either buprenorphine (e.g., Suboxone) or methadone. Though a low prevalence of naltrexone (e.g., Vivitrol) patients is consistent with the broader population of inmates participating in Rhode Island’s medication program, additional research that oversample for naltrexone patients is needed to better understand antagonist medication attitudes in correctional settings. Differences between methadone and buprenorphine patients also demand further investigation.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The Rhode Island department of corrections recently implemented a statewide program offering medications for opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings. Previous studies have shown its ability to reduce overdose risk among inmates after incarceration, and this study furthers our understanding of corrections-based treatment by looking at inmate perceptions. Inmates participating in the program noted its usefulness for preventing withdrawal, decreasing the prevalence of illicit drugs in the correctional facility, improving the overall facility environment for staff and inmates, and facilitating healthy plans for treatment and recovery after release. Inmates also noted areas for improvement, including the need for more in-house recovery support services, addiction education among staff, additional resources to aid transitions to community-based medication treatment, and timely receipt of medication after arrest. Studies like this provide important information to help guide other correctional facilities looking to implement their own pharmacotherapy programs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This qualitative study evaluated patient perceptions among inmates participating in the first state-wide opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy program in prison/jail settings. Patient reported benefits included prevention of withdrawal, decreased demand and supply of illicit drugs in the correctional facilities, general improvements in facility environments, and ability to develop a healthy plan for treatment and recovery after incarceration. Reported suggestions for improvement included offering more diverse in-house recovery support services, educating staff about addiction and medication treatment to reduce patient stigma, providing resources at the front end of incarceration to aid transition to community-based providers, and timely receipt of medication upon incarceration. A limited number of U.S. jails and prisons have implemented comprehensive opioid use disorder medication programs to date, and studies like this provide necessary information to guide program development in additional facilities around the nation. Partnering with criminal justice systems may help ensure smoother transitions between incarceration and community-based systems of care.

- For scientists: This qualitative study evaluated the perceived benefits and challenges of inmates participating in the Rhode Island’s opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy program for correctional facilities. Patients had generally positive perceptions of the program, reporting that pharmacotherapy not only prevented withdrawal, but also decreased demand/supply of illicit drugs in the correctional facilities, improved facility environment for inmates and staff, and promoted recovery-focused post-incarceration plans for treatment and recovery. Inmates also noted program challenges, suggesting the need for additional recovery support services, more staff education on pharmacotherapy to reduce stigma, additional information about transitioning to community-based treatment, and more timely first-dose receipt. Given the Rhode Island program’s demonstrated ability to reduce overdose rates, additional research in this area is essential to help address the opioid overdose epidemic. Previous studies suggest that medication treatment in criminal justice settings may also enhance community-based treatment engagement, and reduce rates of injection drug use and relapse up to 12 months post incarceration. Integrating recovery support services (e.g., mutual help organizations) into criminal justice programs is also shown to benefit long-term outcomes (e.g., reduced recidivism) Therefore, additional research is needed to determine whether a program like this one can be implemented in other facilities around the nation. Given patient concerns and previous studies highlighting stigma among stakeholders, research is also needed to identify effective interventions for stakeholders that address stigma against patients who use medication.

- For policy makers: In 2016, Rhode Island implement the first statewide program offering all FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder in criminal justice settings. Previous studies demonstrate this program’s ability to reduce overdose prevalence post incarceration, and the current study highlights additional benefits from a patient perspective. Results suggested a high level of inmate support for the pharmacotherapy program, highlighting its feasibility and adoptability in correctional facilities. Inmates also noted its usefulness for preventing withdrawal, decreasing the prevalence of illicit drugs in prison, improving the facility environment, and facilitating healthy post-incarceration plans. Importantly, inmates also noted some areas for program improvement (e.g., pharmacotherapy education for staff, coordination between community providers and the department of corrections). Studies like this provide important information to help guide the expansion of these lifesaving programs, and inform the development of new policies and regulations to ensure optimal pharmacotherapy programs in the criminal justice system.

CITATIONS

Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Peterson, M., Clarke, J., Macmadu, A., Truong, A., Pognon, K., … & Stein, L. (2019). The benefits and implementation challenges of the first state-wide comprehensive medication for addictions program in a unified jail and prison setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.016