Characteristics of adults reporting non-prescribed use of buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a safe and evidence-based medication used to treat individuals with opioid use disorder; however, non-prescribed use of buprenorphine can undermine recovery while also marking risk for negative health outcomes. Little is known about relevant predictors, particularly among incarcerated individuals. Authors of this study analyzed data from a sample of incarcerated men and women in addiction treatment to examine predictors of non-prescribed buprenorphine use.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Buprenorphine (often prescribed in formulation with naloxone, known by the brand name Suboxone) is an effective treatment for opioid use disorder, yet concern remains in light of reports of non-prescribed use and risks associated with misuse of buprenorphine. Incarcerated individuals represent a particularly vulnerable group in the context of opioid use disorder and recovery. While little is known about the characteristics of individuals who use non-prescribed buprenorphine, or predictors of such use, even less is known regarding individuals currently or at risk of becoming incarcerated. Knowledge of these predictors could assist with targeted prevention programs and intervention. In this study, authors examine baseline data from a sample of 12,007 incarcerated men and women from a Department of Corrections Substance Abuse Treatment Program to examine characteristics of individuals who engage in non-prescribed buprenorphine use, and predictors of non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the year leading up to their incarceration. In so doing, the authors provide insight into who these individuals are and predisposing risk factors to inform prevention, practice, and policy recommendations for those currently or at risk of becoming incarcerated.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a cross-sectional survey and analysis of baseline data gathered from individuals upon admission to a Department of Corrections Substance Abuse Treatment Program in Kentucky. The primary aim of this study was to examine the prevalence of non-prescribed buprenorphine use among inmates in the year prior to their incarceration, and to examine predictors of said use to understand risk factors for unprescribed use and incarceration. The measured these variables and risk factors using clinician-administered semi-structured during their treatment intake and asking self-report survey questions. In the current analysis, authors included 12,007 individuals who had lived in Kentucky for more than six months in the previous year, were currently serving sentences greater than six months, with “good behaviors” for the past 60 days, and who were admitted to the voluntary six-month treatment program between 2016 and 2018.

Once admitted to the treatment program, participants completed baseline survey administered by a Department of Corrections clinician. Questionnaires included questions that assessed participant demographics (age, gender), alcohol and drug use (e.g., pre-incarceration use of drugs such as heroin and non-prescribed opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, and other synthetic drugs), severity and routes of administration (e.g., intravenous [IV] drug use), and physical health and infectious diseases (e.g., hepatitis C, HIV). The researchers also assessed how important treatment was to participants at admission, and the degree to which participants felt confident in their ability to remain abstinent from substances (“abstinence self-efficacy”). Finally, non-prescribed buprenorphine use was measured by asking participants, “In the 12 months prior to this incarceration, how many months did you use Subutex®, Suboxone®, or buprenorphine that was not prescribed for you?”. The researchers later collapsed responses to this question into a binary “never” vs. “any” (in the past year) score. The researchers then examined demographic characteristics of individuals who reported vs. denied non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year, as well as other correlates of non-prescribed use using the variables they assessed at baseline.

Participants in the study included 12,007 patients. Participants were 34.5 years old, on average; the majority of this sample was male (84.1%), White (84.5%), maintained at least part-time employment (63.6%), and held a high school diploma/GED (72.0%). The majority had also engaged in substance use disorder treatment, including inpatient detoxification, previously (71.0%). Reports of past year/pre-incarceration drug use was variable, with reports of alcohol (52.9%), cannabis (58.3%), non-prescribed opioid medications (45.8%), heroin (29.1%), amphetamine (51.9%), cocaine/crack (25.6%), hallucinogens (6.8%), synthetic drug (e.g., cannabinoids; 14.6%), and kratom use (.2%). Non-prescribed buprenorphine use, methadone, and sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines) were reported by 21.8%, 9.0%, and 26.7%, respectively.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

A total of 26.2% (n = 3,142) reported non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year and 21.8% reported non-prescribed buprenorphine in the past 30 days prior to incarceration.

Compared to participants who reported no non-prescribed use in the past year, those who did were more likely to be younger, White, and to reside in rural and Appalachian regions of Kentucky. Individuals with non-prescribed use in the past year were also more likely to report prior IV drug use and a diagnosis of hepatitis B and C. Their substance use severity was also significantly higher, treatment history more extensive, and past-year substance use more prevalent across all measured classes except alcohol.

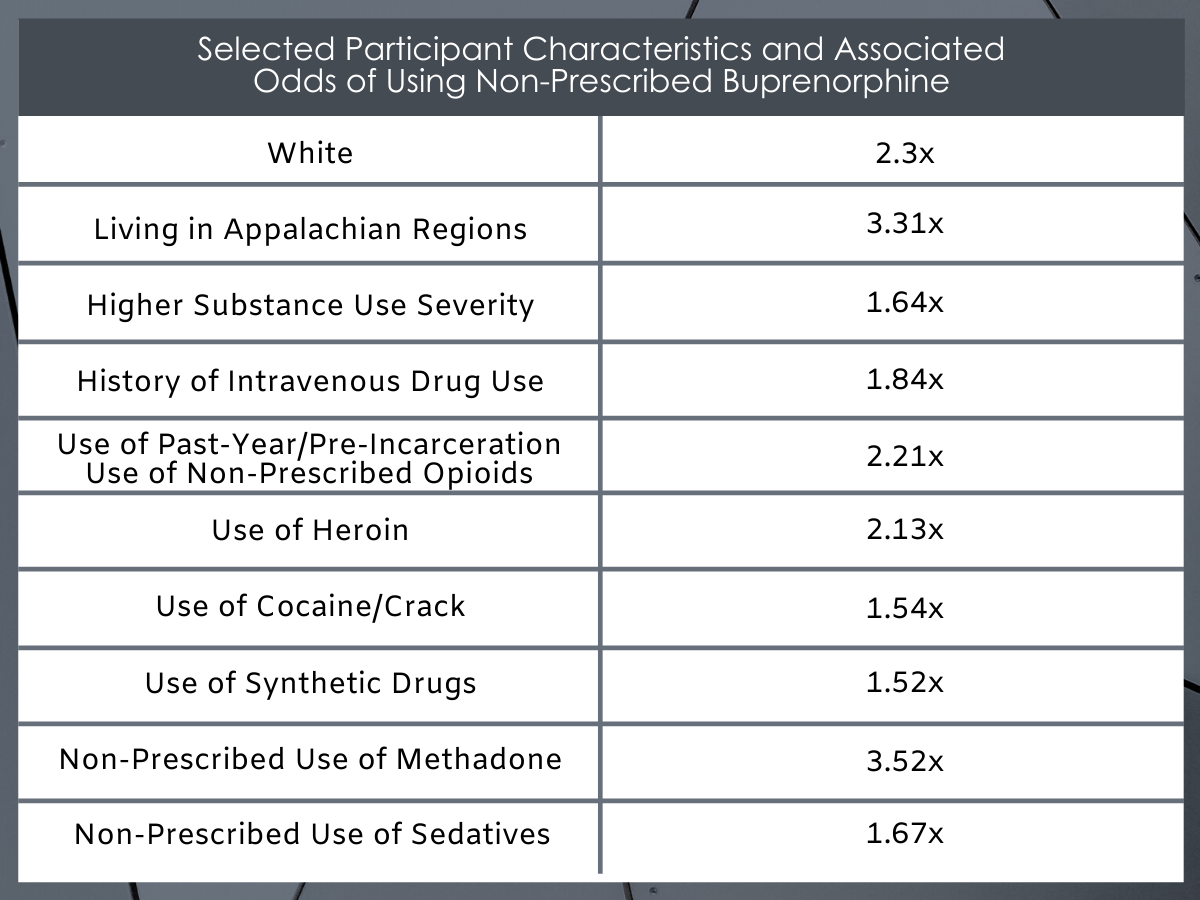

Figure 1. Odds are presented in the form of adjusted odds ratios, indicating increased or decreased odds of using non-prescribed buprenorphine based on specific characteristics, and while statistically controlling for other variables. Odd ratios >1 indicate increased chances of using non-prescribed buprenorphine (e.g., 2.52 = 2.52 times greater odds or 152% higher likelihood), while odds ratios <1 indicated decreased chances.

When each of the above-mentioned variables were entered into the statistical model together, the researchers found that most of them were correlated with non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year. Notably, the percent increase in the likelihood of buprenorphine misuse varied cross different geo-demographic and clinical variables. Specifically, a higher percentage increase in the likelihood of non-prescribed use was associated with White race, residing in Appalachian regions, higher substance use severity, history of intravenous drug use, and past-year/pre-incarceration use of non-prescribed opioid pain relievers, heroin, cocaine/crack, synthetic drugs, and non-prescribed use of methadone and sedatives. By far the strongest correlates with non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year were White race, Appalachian residence, and past-year use of heroin, non-prescribed opioid pain killers, and non-prescribed methadone use. Appalachian residence has been linked to opioid misuse and attributed to economic downturn, rurality, and limited access to treatment. As such, this is consistent with findings that the majority of non-prescribed buprenorphine use motivated by individuals’ desire to manage withdrawal symptoms.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study provides a breakdown of the characteristics of incarcerated individuals in Kentucky who self-report non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year. Based on their reports, buprenorphine appears more common among younger White men who reside in rural and Appalachian regions of Kentucky.

As would be expected, the prevalence of non-prescribed buprenorphine use was also higher among individuals who reported more severe substance use in the past year, including use of illicit drugs or illicit use of prescription drugs (e.g., prescription opioids, methadone, sedatives). Notably, non-prescribed buprenorphine use was also associated with lower abstinence self-efficacy, indicating lower confidence in these individuals’ perceived ability to stop and abstain from substance use. Thus, individuals who misused buprenorphine in the past year tended to be more severe on other measures. Greater severity might also indicate greater motivation to change, yet lower self-efficacy is an important barrier to address.

The results of this study require follow up in the region to explicate the pattern of results observed. On the one hand, these results could point to possible barriers to buprenorphine treatment, including under-prescription of buprenorphine among Kentucky residents, and participants’ decision to secure and use buprenorphine without prescription in attempt to medicate themselves. On the other hand, non-prescribed buprenorphine use might be accounted for by recreational use of the drug by itself, in combination with other drugs, or as one of several options among polysubstance using individuals. Although reasons for non-prescribed use were not measured in the current study, they have been reported elsewhere among non-incarcerated samples. That is, while many individuals have been shown to misuse buprenorphine to experience pleasurable effects (“get high”), it is far more common for individuals to use buprenorphine to stave off opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The cross-sectional nature of this study and reliance on single-item self-report measures limits directional and causal inference.

- Reliance on self-reports collected by clinicians staffed by the Department of Corrections could have led to response bias (e.g., underreporting of criminal drug activity).

- The authors asked about use of buprenorphine that was not prescribed to them but not about misuse of prescribed buprenorphine. This likely led to an underestimate of the prevalence of non-prescribed buprenorphine use, which includes situations where individuals misuse their own prescription.

- Relatedly, authors did not gather information about dosing, frequency, or duration (e.g., days, continuous/discontinuous intervals) of non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the prior year.

- The authors were unable to account for the participants’ motives for taking buprenorphine (which have been reported in other studies), or for participants’ histories of treatment using buprenorphine (e.g., whether they had received prescriptions for MAT in the past, or their history of successful/unsuccessful treatment).

- The exclusive focus on Kentucky residents was a strength for local purposes but may limit generalizability.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Over one in four of incarcerated Kentucky residents admitted to the Department of Corrections substance use treatment program reported non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year. There were many factors related to non-prescribed buprenorphine use; however, the characteristics and behaviors most associated with non-prescribed buprenorphine use were White race, Appalachian residence, and past-year use of heroin, non-prescribed opioids, and non-prescribed methadone use. Individuals reporting non-prescribed buprenorphine use were also more likely to be younger, male, and report lower confidence in their ability to stop and abstain from drug use. Lack of confidence might be related to previous failed attempts to abstain, and/or greater substance use disorder severity among these individuals. Fortunately, evidence-based treatment is available and can assist with increasing individuals’ confidence, skills, and recovery potential. In addition, building in accountability and other supports, such as attendance at Narcotics Anonymous meetings, can significantly increase the chances of buprenorphine treatment success.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Over a quarter of inmates admitted to a voluntary substance use treatment program in Kentucky reported non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the year leading up their incarceration. There were many factors related to non-prescribed use. However, the strongest correlates of non-prescribed use were White race, Appalachian residence, and past-year use of heroin, non-prescribed opioids, and non-prescribed methadone use. In addition, these individuals were more likely to be younger, evidenced more severe substance use, and more extensive treatment histories. Thus, their lack of confidence in abstaining from substance use might relate to the severity of their current use, previous failed treatment attempts, and/or lack of access to desired medications like buprenorphine. In addition to preventing recreational buprenorphine use, which is critical, efforts are also needed to expand providers’ reach, increase prescription access, and support medication adherence in rural settings to prevent avoidable misuse among those seeking buprenorphine to aid in their recovery. These efforts might also include expanded treatment options, including buprenorphine injections, to limit risk for non-prescribed buprenorphine use.

- For scientists: Over 25% of inmates (n = 3,142) admitted to a Kentucky-based substance use disorder treatment program reported non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the year leading up to their incarceration. Though most variables examined were correlated with non-prescribed buprenorphine use, White race, Appalachian residence, and past-year use of heroin, non-prescribed opioids, and non-prescribed methadone use produced the highest odds ratios. Given the profile of the individuals reporting non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the current study, misuse may represent another form of recreational drug use, another substance used in conjunction with others among polysubstance using individuals, and/or use of buprenorphine for recovery purposes in the absence of a prescription. Unfortunately, due to the limitations inherent with this study, it is not possible to distinguish from among these possibilities.Though reported among non-incarcerated samples, future research is needed examine reasons for non-prescribed buprenorphine use among incarcerated individuals specifically. In addition, the narrow definition of non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the current study does not include non-prescribed use of buprenorphine following an initial prescription (e.g., misuse of one’s personal and legitimate prescription). An expanded definition is needed to derive more accurate estimates of prevalence. Lastly, future self-report studies benefit from having non-correctional staff administer de-identified surveys, in addition to providing explicit privacy and confidentiality protections, to reduce possible participant response bias. Caution is also warranted with regard to characterizing prevalence vs. incidence (i.e., proportion or rate of new “cases” or behaviors) in future research to ensure accurate reporting and limit undue concerns regarding buprenorphine prescription (e.g., fear of non-prescribed buprenorphine use or diversion).

- For policy makers: Over one in four Kentucky inmates voluntarily admitted to substance use treatment reported non-prescribed buprenorphine use in the past year. As displayed in Figure 1, there were several characteristics and behaviors related to the likelihood of non-prescribed buprenorphine use. At a glance, the profile of individuals most at risk for non-prescribed buprenorphine use included younger White men residing in rural and Appalachian regions of Kentucky. These individuals also reported more extensive and severe substance use, previous substance use treatment, and were more likely to report chronic and infectious disease and intravenous drug use. From a public health perspective, these findings provide critical insight into high-risk geographic regions as well as individual profiles that might become the target of enhanced prevention efforts. While the results of this study do not include reasons for buprenorphine misuse, which are varied, increasing provider and prescription access to these individuals within high-risk geographic regions might help offset preventable risk for non-prescribed buprenorphine use among those seeking to use buprenorphine as prescribed. Additional policy recommendations might include funding allocations to support expansion of prescription access to rural areas, including diverse treatment options such as injectable buprenorphine to prevent buprenorphine misuse, as well as integration of buprenorphine treatment into correctional facilities.

CITATIONS

Smith, K. E., Tillson, M. D., Staton, M., & Winston, E. M. (2020). Characterization of diverted buprenorphine use among adults entering corrections-based drug treatment in Kentucky. Drug and alcohol dependence, 208, 107837. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107837