l

Sustaining recovery after an initial period of abstinence can be challenging, associated with relapse for some that occurs within the first 3 months after discharge. In addition to the use of empirically-supported mutual-help linkages and continuing care to help improve outcomes post-discharge, tailored strategies to enhance interventions may also be useful. Developing such personalized treatments requires identifying the key characteristics of individuals who have successfully maintained long-term recovery, as well as understanding the traits of those more prone to relapse. Incorporating strategies that take into account patients’ specific personality traits may be one such personalized approach.

Personality traits, broadly defined, refer to habitual patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that characterize an individual. The most widely validated framework for understanding “normal” personality is the Five-Factor Model, which includes five broad dimensions: Neuroticism (tendency toward negative emotions), Extraversion (tendency toward positive emotions), Openness (willingness to experience new things), Agreeableness (cooperativeness and compassion), and Conscientiousness (organization and dependability). In this study, the researchers examined whether these 5 personality traits, assessed at baseline, could predict both short-term and long-term recovery outcomes.

This longitudinal study used data from the Stavanger Study of Trajectories of Addiction, which tracked participants over 10 years in Norway. The study examined 208 people from 10 addiction treatment centers within the Stavanger University Hospital area. These centers provided both inpatient (where participants stayed for 3 to 12 months) and outpatient (where treatment could last several years) services for addiction. To be part of the study, participants had to meet specific criteria for harmful use, dependency, or gambling problems according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Participants joined the study when they began a new treatment episode between March 2012 and December 2016. The study then followed up on their recovery every year, particularly in the first and sixth to eighth years. Data was collected through several assessments in the first year and annually afterward.

At the start of the study, researchers gathered basic information about participants, like their year and country of birth, living situation, the age they first used substances, and their education level through an interview. Gender was noted by the research team. They also assessed personality traits during the first 6 months using a detailed questionnaire that looks at 5 main personality traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness based on responses to 240 questions, with answers rated on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The scores were adjusted based on Norwegian norms to see how participants compared to the average person.

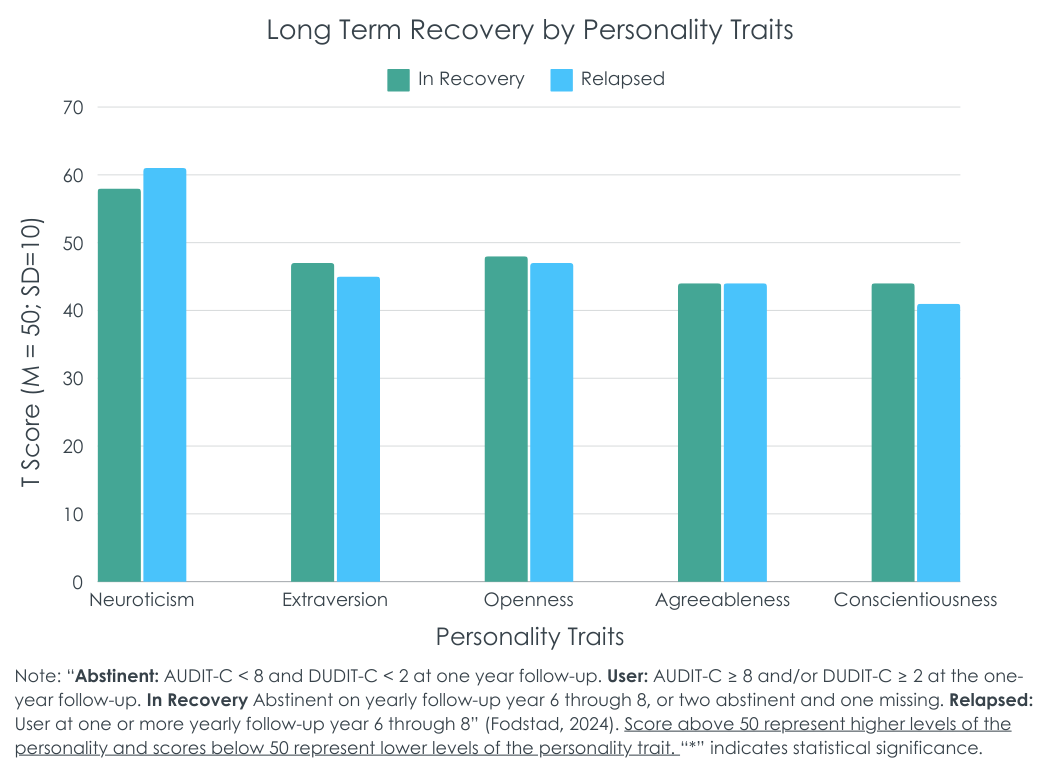

Participants completed a screener to measure alcohol use (AUDIT-C) and other drug use (DUDIT-C). Recovery in the short term (1-year post-treatment) was defined by specific scores indicating either abstinence/lower-risk use (AUDIT-C < 8 and DUDIT-C < 2) or non-lower risk use (AUDIT-C >= 8 and/or DUDIT-C >=2). Long-term recovery was examined at 3 time points: 6, 7, and 8 years post-treatment. If they were in the abstinence/lower-risk group on at least 2 of 3 annual follow-ups (they could be missing one), they were considered “recovered”, referred to here as “in recovery”. If they were in the continued use group at 1 or more of the 3 follow-ups, they were classified as relapsed. Participants with 2+ missing follow-ups were excluded from the final analysis.

Analyses examined how each of the 5 personality traits measured in the first 6 months of treatment predicted alcohol and drug use 1 year after entering treatment, as well as 6-8 years after entering treatment, in two ways. In the first they examined whether traits were associated with a dichotomous indicator. Participants were 25-28 years old (depending on the group) at the beginning of the study, 57-63% men, and began to use substances, on average, at 13 years old.

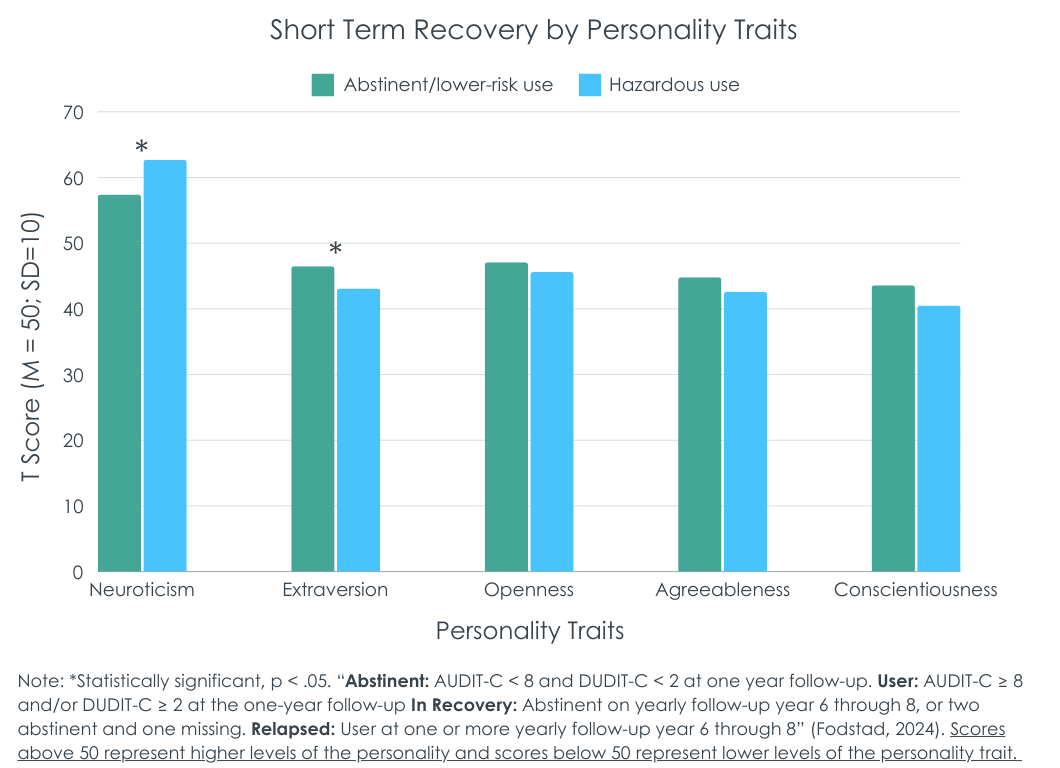

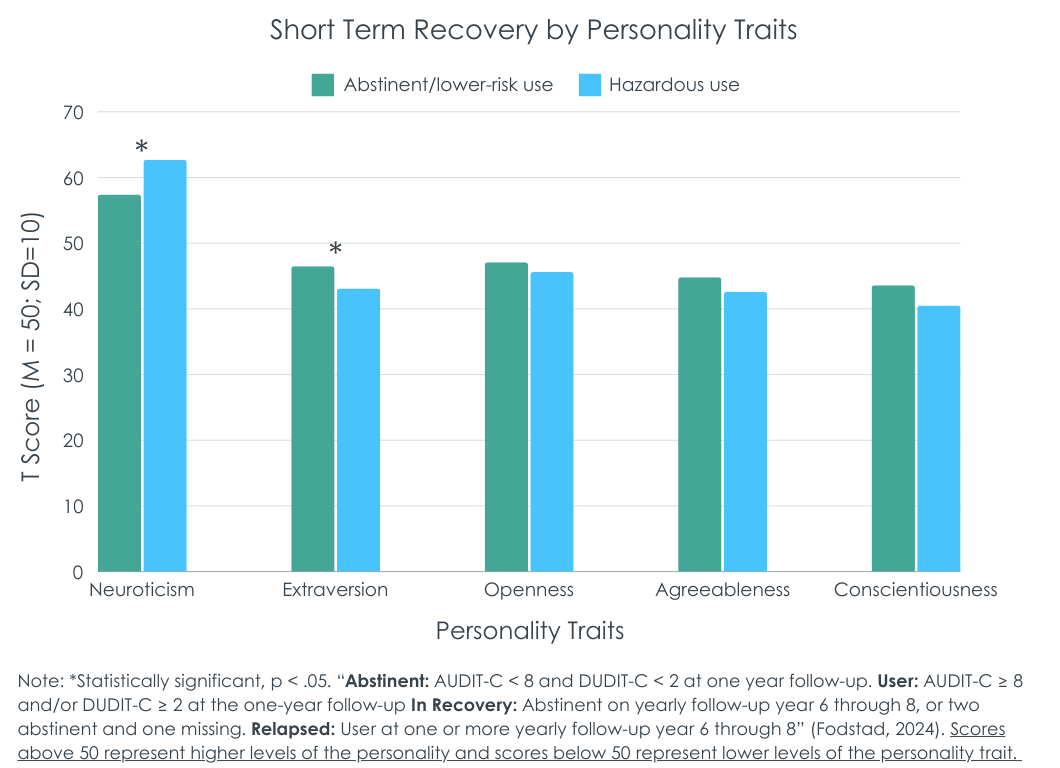

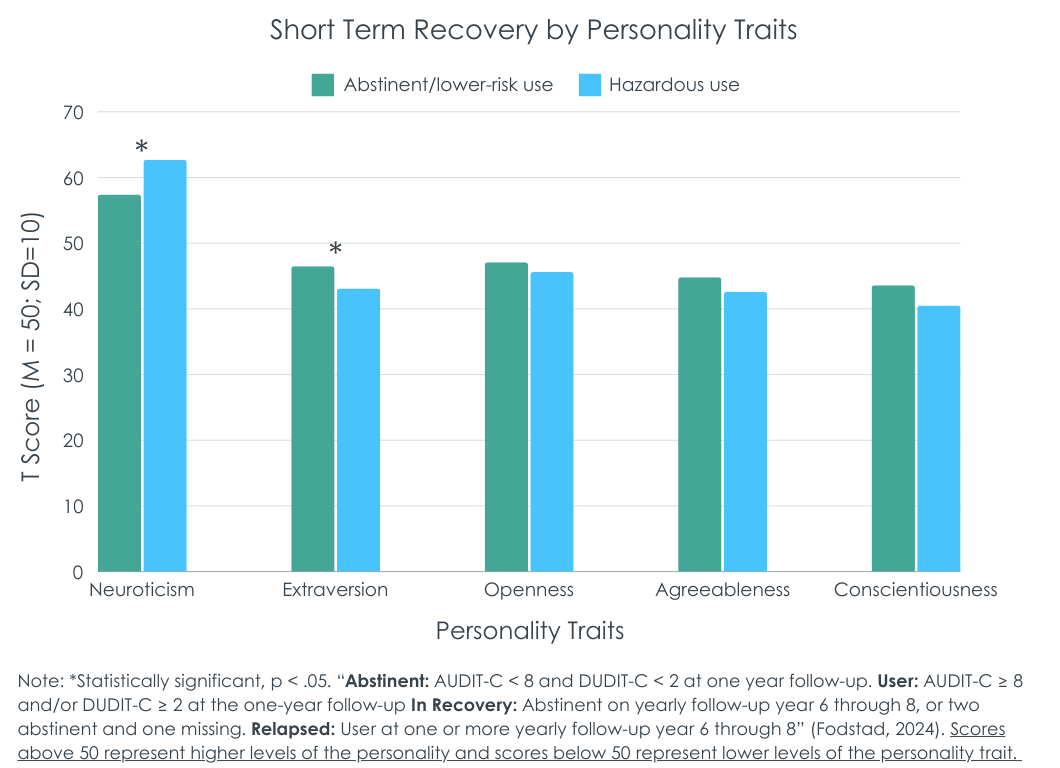

Lower neuroticism and higher extraversion predicted short-term abstinence/lower-risk use

Higher levels of neuroticism were associated with a lower likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use (see figure below). Conversely, higher levels of extraversion were associated with a higher likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use.

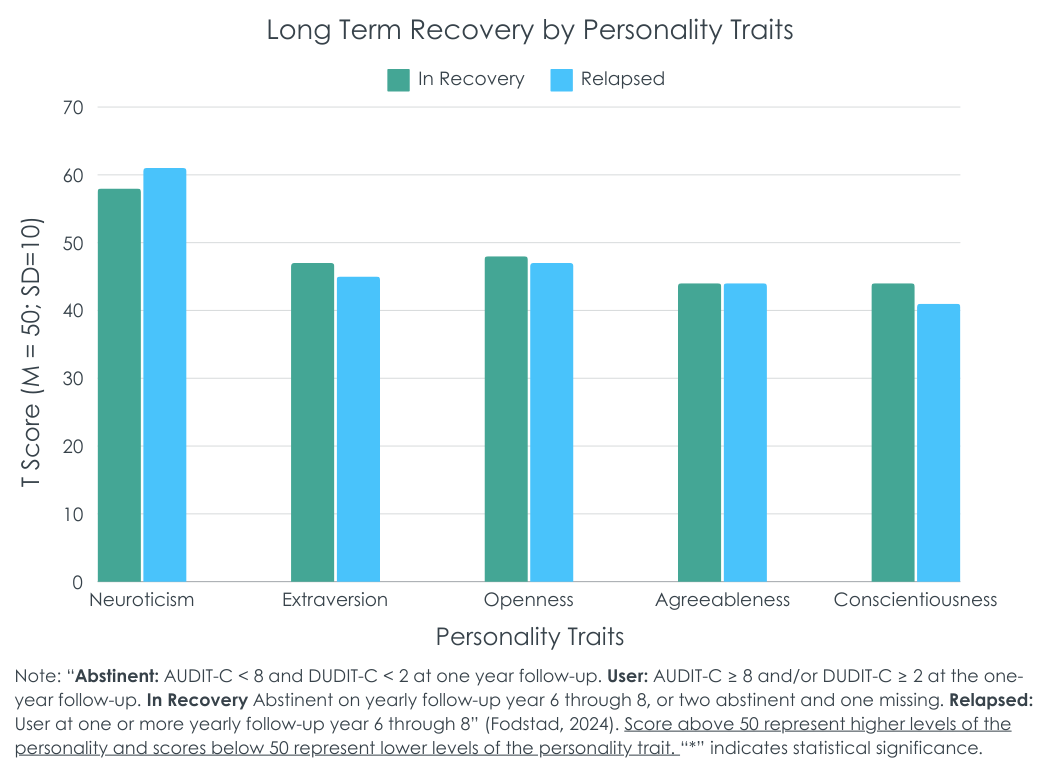

Personality traits were not associated with substance use at long-term follow-up

Substance use 6 to 8 years post-treatment was not associated with any of the 5 personality factors measured during the first 6 months of the study. However, subsidiary analyses showed that higher levels of anxiety and vulnerability, both facets of neuroticism, were associated with lower likelihood of recovery, defined as abstinence/lower-risk use at 2 of the 3 follow-ups. Conversely, higher levels of self-discipline, which is a facet of conscientiousness, was associated with greater likelihood of recovery.

Positive outcomes for alcohol use tended to be lower-risk drinking and for drug use tended to be abstinence

When examining personality trait effects on abstinence (any use) and degree of substance use separately at 1-year follow-up, higher neuroticism, lower extraversion, and lower conscientiousness predicted drug abstinence while greater openness predicted the degree of drug use when present. Higher neuroticism predicted both alcohol abstinence and more alcohol use when present while conscientiousness predicted more alcohol use when present (but not abstinence).

When examining these patterns for 6-8 year follow-up trajectories, the effect of higher extraversion on drug abstinence decreased over time. The effects of lower neuroticism, higher extraversion, and higher conscientiousness on alcohol abstinence also decrease over time. In other words, the effects of personality traits during Year 1 become more muted by the 6-8 year follow-ups.

This study found, among participants within the first year following treatment, that higher neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of hazardous/harmful substance use, while lower neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of being in recovery (defined in this study as abstinence/lower-risk use on at least 2 of the 3 long term follow-ups at years 6-8 after entering treatment). High neuroticism is strongly associated with not only substance use disorder, but also depressive and anxiety disorders. It is likely that those with lower neuroticism had less likelihood of experiencing mental health challenges either due to psychiatric disorder or in response to stressful life events. Such individuals with reduced mental health burden may be better able to maintain or expand on gains made during addiction treatment. Other studies too show that individuals high in neuroticism, measured as “negative emotionality”, do not improve as much as their counterparts on abstinence self-efficacy during treatment and may benefit from additional attention to their confidence when faced with risky situations (e.g., through additional role plays when addressing assertive drink/drug refusal skills). On the other hand, those high in extraversion may have more robust social networks and/or better able to engage with recovery supports in the community, many of which, like mutual-help groups, rely on peer support and promote better outcomes when participants socialize with other members. Those lower in extraversion may need additional support with these recovery support activities more dependent on social interaction.

Importantly, personality traits did not predict substance use outcomes 6-8 years after treatment. This may actually be good news. It suggests that over the long-term individual personality traits measured early in the recovery process do not predict long-term outcome. Furthermore, many models of recovery, such as 12-step approaches, actually prescribe and emphasize the need to change personality structure in order to get and stay in long-term remission and so many of those successfully in recovery in this study may have purposively enacted such personality change in the course of their recovery. Future work examining personality and long-term recovery might re-assess traits to examine whether certain shifts (e.g., reduced neuroticism) are associated with better recovery outcomes.

Strategies to help individuals with higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of extraversion may improve short-term recovery outcomes. However, long-term recovery outcomes do not depend as much on personality traits measured early in recovery. This is potentially good news as positive recovery outcomes can be achieved irrespective of one’s personality traits measured early in recovery. This may be because successful recovery can be considered in some respects achievable with ongoing concerted efforts to change one’s personality.

Fodstad, E. C., Erga, A. H., Pallesen, S., Ushakova, A., & Erevik, E. K. (2024). Personality traits as predictors of recovery among patients with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209360.

l

Sustaining recovery after an initial period of abstinence can be challenging, associated with relapse for some that occurs within the first 3 months after discharge. In addition to the use of empirically-supported mutual-help linkages and continuing care to help improve outcomes post-discharge, tailored strategies to enhance interventions may also be useful. Developing such personalized treatments requires identifying the key characteristics of individuals who have successfully maintained long-term recovery, as well as understanding the traits of those more prone to relapse. Incorporating strategies that take into account patients’ specific personality traits may be one such personalized approach.

Personality traits, broadly defined, refer to habitual patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that characterize an individual. The most widely validated framework for understanding “normal” personality is the Five-Factor Model, which includes five broad dimensions: Neuroticism (tendency toward negative emotions), Extraversion (tendency toward positive emotions), Openness (willingness to experience new things), Agreeableness (cooperativeness and compassion), and Conscientiousness (organization and dependability). In this study, the researchers examined whether these 5 personality traits, assessed at baseline, could predict both short-term and long-term recovery outcomes.

This longitudinal study used data from the Stavanger Study of Trajectories of Addiction, which tracked participants over 10 years in Norway. The study examined 208 people from 10 addiction treatment centers within the Stavanger University Hospital area. These centers provided both inpatient (where participants stayed for 3 to 12 months) and outpatient (where treatment could last several years) services for addiction. To be part of the study, participants had to meet specific criteria for harmful use, dependency, or gambling problems according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Participants joined the study when they began a new treatment episode between March 2012 and December 2016. The study then followed up on their recovery every year, particularly in the first and sixth to eighth years. Data was collected through several assessments in the first year and annually afterward.

At the start of the study, researchers gathered basic information about participants, like their year and country of birth, living situation, the age they first used substances, and their education level through an interview. Gender was noted by the research team. They also assessed personality traits during the first 6 months using a detailed questionnaire that looks at 5 main personality traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness based on responses to 240 questions, with answers rated on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The scores were adjusted based on Norwegian norms to see how participants compared to the average person.

Participants completed a screener to measure alcohol use (AUDIT-C) and other drug use (DUDIT-C). Recovery in the short term (1-year post-treatment) was defined by specific scores indicating either abstinence/lower-risk use (AUDIT-C < 8 and DUDIT-C < 2) or non-lower risk use (AUDIT-C >= 8 and/or DUDIT-C >=2). Long-term recovery was examined at 3 time points: 6, 7, and 8 years post-treatment. If they were in the abstinence/lower-risk group on at least 2 of 3 annual follow-ups (they could be missing one), they were considered “recovered”, referred to here as “in recovery”. If they were in the continued use group at 1 or more of the 3 follow-ups, they were classified as relapsed. Participants with 2+ missing follow-ups were excluded from the final analysis.

Analyses examined how each of the 5 personality traits measured in the first 6 months of treatment predicted alcohol and drug use 1 year after entering treatment, as well as 6-8 years after entering treatment, in two ways. In the first they examined whether traits were associated with a dichotomous indicator. Participants were 25-28 years old (depending on the group) at the beginning of the study, 57-63% men, and began to use substances, on average, at 13 years old.

Lower neuroticism and higher extraversion predicted short-term abstinence/lower-risk use

Higher levels of neuroticism were associated with a lower likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use (see figure below). Conversely, higher levels of extraversion were associated with a higher likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use.

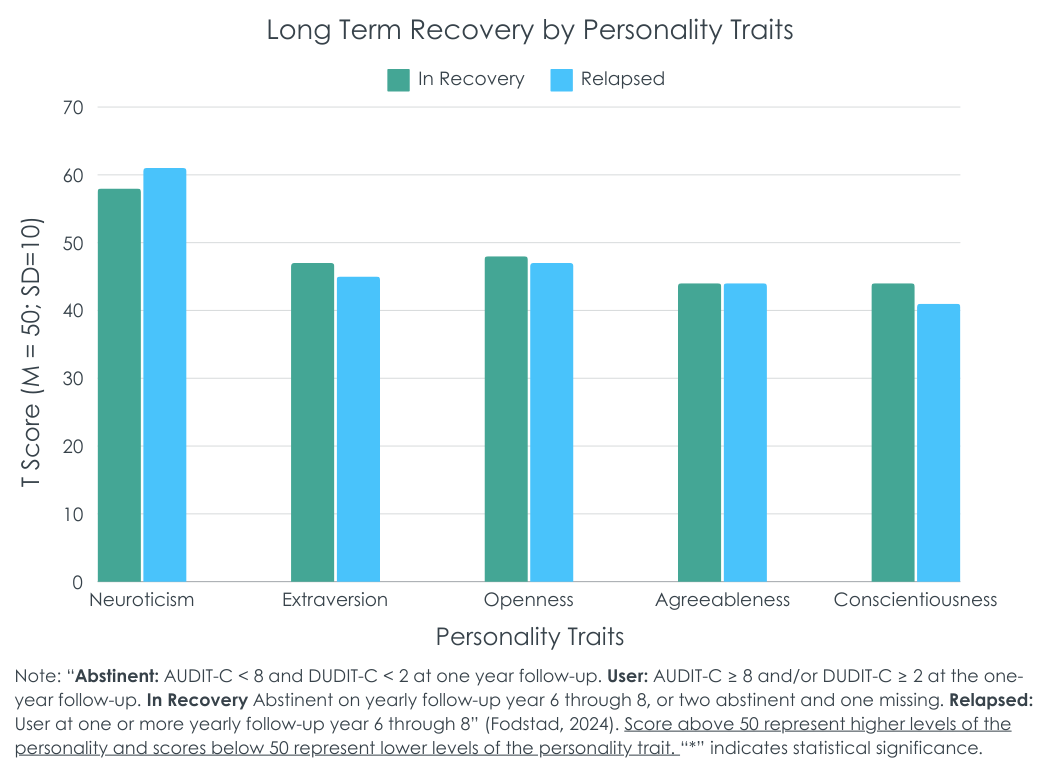

Personality traits were not associated with substance use at long-term follow-up

Substance use 6 to 8 years post-treatment was not associated with any of the 5 personality factors measured during the first 6 months of the study. However, subsidiary analyses showed that higher levels of anxiety and vulnerability, both facets of neuroticism, were associated with lower likelihood of recovery, defined as abstinence/lower-risk use at 2 of the 3 follow-ups. Conversely, higher levels of self-discipline, which is a facet of conscientiousness, was associated with greater likelihood of recovery.

Positive outcomes for alcohol use tended to be lower-risk drinking and for drug use tended to be abstinence

When examining personality trait effects on abstinence (any use) and degree of substance use separately at 1-year follow-up, higher neuroticism, lower extraversion, and lower conscientiousness predicted drug abstinence while greater openness predicted the degree of drug use when present. Higher neuroticism predicted both alcohol abstinence and more alcohol use when present while conscientiousness predicted more alcohol use when present (but not abstinence).

When examining these patterns for 6-8 year follow-up trajectories, the effect of higher extraversion on drug abstinence decreased over time. The effects of lower neuroticism, higher extraversion, and higher conscientiousness on alcohol abstinence also decrease over time. In other words, the effects of personality traits during Year 1 become more muted by the 6-8 year follow-ups.

This study found, among participants within the first year following treatment, that higher neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of hazardous/harmful substance use, while lower neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of being in recovery (defined in this study as abstinence/lower-risk use on at least 2 of the 3 long term follow-ups at years 6-8 after entering treatment). High neuroticism is strongly associated with not only substance use disorder, but also depressive and anxiety disorders. It is likely that those with lower neuroticism had less likelihood of experiencing mental health challenges either due to psychiatric disorder or in response to stressful life events. Such individuals with reduced mental health burden may be better able to maintain or expand on gains made during addiction treatment. Other studies too show that individuals high in neuroticism, measured as “negative emotionality”, do not improve as much as their counterparts on abstinence self-efficacy during treatment and may benefit from additional attention to their confidence when faced with risky situations (e.g., through additional role plays when addressing assertive drink/drug refusal skills). On the other hand, those high in extraversion may have more robust social networks and/or better able to engage with recovery supports in the community, many of which, like mutual-help groups, rely on peer support and promote better outcomes when participants socialize with other members. Those lower in extraversion may need additional support with these recovery support activities more dependent on social interaction.

Importantly, personality traits did not predict substance use outcomes 6-8 years after treatment. This may actually be good news. It suggests that over the long-term individual personality traits measured early in the recovery process do not predict long-term outcome. Furthermore, many models of recovery, such as 12-step approaches, actually prescribe and emphasize the need to change personality structure in order to get and stay in long-term remission and so many of those successfully in recovery in this study may have purposively enacted such personality change in the course of their recovery. Future work examining personality and long-term recovery might re-assess traits to examine whether certain shifts (e.g., reduced neuroticism) are associated with better recovery outcomes.

Strategies to help individuals with higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of extraversion may improve short-term recovery outcomes. However, long-term recovery outcomes do not depend as much on personality traits measured early in recovery. This is potentially good news as positive recovery outcomes can be achieved irrespective of one’s personality traits measured early in recovery. This may be because successful recovery can be considered in some respects achievable with ongoing concerted efforts to change one’s personality.

Fodstad, E. C., Erga, A. H., Pallesen, S., Ushakova, A., & Erevik, E. K. (2024). Personality traits as predictors of recovery among patients with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209360.

l

Sustaining recovery after an initial period of abstinence can be challenging, associated with relapse for some that occurs within the first 3 months after discharge. In addition to the use of empirically-supported mutual-help linkages and continuing care to help improve outcomes post-discharge, tailored strategies to enhance interventions may also be useful. Developing such personalized treatments requires identifying the key characteristics of individuals who have successfully maintained long-term recovery, as well as understanding the traits of those more prone to relapse. Incorporating strategies that take into account patients’ specific personality traits may be one such personalized approach.

Personality traits, broadly defined, refer to habitual patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that characterize an individual. The most widely validated framework for understanding “normal” personality is the Five-Factor Model, which includes five broad dimensions: Neuroticism (tendency toward negative emotions), Extraversion (tendency toward positive emotions), Openness (willingness to experience new things), Agreeableness (cooperativeness and compassion), and Conscientiousness (organization and dependability). In this study, the researchers examined whether these 5 personality traits, assessed at baseline, could predict both short-term and long-term recovery outcomes.

This longitudinal study used data from the Stavanger Study of Trajectories of Addiction, which tracked participants over 10 years in Norway. The study examined 208 people from 10 addiction treatment centers within the Stavanger University Hospital area. These centers provided both inpatient (where participants stayed for 3 to 12 months) and outpatient (where treatment could last several years) services for addiction. To be part of the study, participants had to meet specific criteria for harmful use, dependency, or gambling problems according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Participants joined the study when they began a new treatment episode between March 2012 and December 2016. The study then followed up on their recovery every year, particularly in the first and sixth to eighth years. Data was collected through several assessments in the first year and annually afterward.

At the start of the study, researchers gathered basic information about participants, like their year and country of birth, living situation, the age they first used substances, and their education level through an interview. Gender was noted by the research team. They also assessed personality traits during the first 6 months using a detailed questionnaire that looks at 5 main personality traits: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness based on responses to 240 questions, with answers rated on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The scores were adjusted based on Norwegian norms to see how participants compared to the average person.

Participants completed a screener to measure alcohol use (AUDIT-C) and other drug use (DUDIT-C). Recovery in the short term (1-year post-treatment) was defined by specific scores indicating either abstinence/lower-risk use (AUDIT-C < 8 and DUDIT-C < 2) or non-lower risk use (AUDIT-C >= 8 and/or DUDIT-C >=2). Long-term recovery was examined at 3 time points: 6, 7, and 8 years post-treatment. If they were in the abstinence/lower-risk group on at least 2 of 3 annual follow-ups (they could be missing one), they were considered “recovered”, referred to here as “in recovery”. If they were in the continued use group at 1 or more of the 3 follow-ups, they were classified as relapsed. Participants with 2+ missing follow-ups were excluded from the final analysis.

Analyses examined how each of the 5 personality traits measured in the first 6 months of treatment predicted alcohol and drug use 1 year after entering treatment, as well as 6-8 years after entering treatment, in two ways. In the first they examined whether traits were associated with a dichotomous indicator. Participants were 25-28 years old (depending on the group) at the beginning of the study, 57-63% men, and began to use substances, on average, at 13 years old.

Lower neuroticism and higher extraversion predicted short-term abstinence/lower-risk use

Higher levels of neuroticism were associated with a lower likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use (see figure below). Conversely, higher levels of extraversion were associated with a higher likelihood of abstinence/lower-risk use.

Personality traits were not associated with substance use at long-term follow-up

Substance use 6 to 8 years post-treatment was not associated with any of the 5 personality factors measured during the first 6 months of the study. However, subsidiary analyses showed that higher levels of anxiety and vulnerability, both facets of neuroticism, were associated with lower likelihood of recovery, defined as abstinence/lower-risk use at 2 of the 3 follow-ups. Conversely, higher levels of self-discipline, which is a facet of conscientiousness, was associated with greater likelihood of recovery.

Positive outcomes for alcohol use tended to be lower-risk drinking and for drug use tended to be abstinence

When examining personality trait effects on abstinence (any use) and degree of substance use separately at 1-year follow-up, higher neuroticism, lower extraversion, and lower conscientiousness predicted drug abstinence while greater openness predicted the degree of drug use when present. Higher neuroticism predicted both alcohol abstinence and more alcohol use when present while conscientiousness predicted more alcohol use when present (but not abstinence).

When examining these patterns for 6-8 year follow-up trajectories, the effect of higher extraversion on drug abstinence decreased over time. The effects of lower neuroticism, higher extraversion, and higher conscientiousness on alcohol abstinence also decrease over time. In other words, the effects of personality traits during Year 1 become more muted by the 6-8 year follow-ups.

This study found, among participants within the first year following treatment, that higher neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of hazardous/harmful substance use, while lower neuroticism was associated with greater likelihood of being in recovery (defined in this study as abstinence/lower-risk use on at least 2 of the 3 long term follow-ups at years 6-8 after entering treatment). High neuroticism is strongly associated with not only substance use disorder, but also depressive and anxiety disorders. It is likely that those with lower neuroticism had less likelihood of experiencing mental health challenges either due to psychiatric disorder or in response to stressful life events. Such individuals with reduced mental health burden may be better able to maintain or expand on gains made during addiction treatment. Other studies too show that individuals high in neuroticism, measured as “negative emotionality”, do not improve as much as their counterparts on abstinence self-efficacy during treatment and may benefit from additional attention to their confidence when faced with risky situations (e.g., through additional role plays when addressing assertive drink/drug refusal skills). On the other hand, those high in extraversion may have more robust social networks and/or better able to engage with recovery supports in the community, many of which, like mutual-help groups, rely on peer support and promote better outcomes when participants socialize with other members. Those lower in extraversion may need additional support with these recovery support activities more dependent on social interaction.

Importantly, personality traits did not predict substance use outcomes 6-8 years after treatment. This may actually be good news. It suggests that over the long-term individual personality traits measured early in the recovery process do not predict long-term outcome. Furthermore, many models of recovery, such as 12-step approaches, actually prescribe and emphasize the need to change personality structure in order to get and stay in long-term remission and so many of those successfully in recovery in this study may have purposively enacted such personality change in the course of their recovery. Future work examining personality and long-term recovery might re-assess traits to examine whether certain shifts (e.g., reduced neuroticism) are associated with better recovery outcomes.

Strategies to help individuals with higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of extraversion may improve short-term recovery outcomes. However, long-term recovery outcomes do not depend as much on personality traits measured early in recovery. This is potentially good news as positive recovery outcomes can be achieved irrespective of one’s personality traits measured early in recovery. This may be because successful recovery can be considered in some respects achievable with ongoing concerted efforts to change one’s personality.

Fodstad, E. C., Erga, A. H., Pallesen, S., Ushakova, A., & Erevik, E. K. (2024). Personality traits as predictors of recovery among patients with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 162. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2024.209360.