What the US Can Learn From the UK About Opioid Treatment in Prisons

In the US, criminal justice populations have higher rates of opioid use disorder than the general population and are at especially high risk for drug overdose death. The prison system, however, has traditionally been opposed to including evidence-based agonist medications like Suboxone and methadone in their drug treatment programs. This United Kingdom-based study investigated if receiving Suboxone or methadone before release increases or decreases risk of death after release.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Agonist medications for opioid use disorder, like buprenorphine (often referred to by its brand name Suboxone), and methadone increase rates of drug test-validated periods of opioid abstinence by 70% or more compared to placebo in gold-standard randomized controlled trials. Naturalistic studies find that taking these medications are associated with a 50-75% decreased risk of death – a majority of which is accounted for by decreased risk of overdose death specifically. Individuals in jails and prisons deserve special attention, however, because their rates of opioid use disorder are six times higher than in the general population. They may also be at particularly high risk of overdose because their acquired tolerance for opioids goes down while in prison if not on an agonist medication. Then, upon release, if they use an amount of opioid similar to before their prison time, they could overdose and die because their bodies are no longer used to that larger amount. Furthermore, whatever routine they had before imprisonment (i.e., from whom they purchased opioids) may be thrown off upon release. For example, they may need to obtain drugs from a new source who sells a more potent form of their opioid of choice. Relatively less is known about the effects of receiving opioids agonist medications while in jail or prison on their outcomes after release. This is what was investigated in this study conducted in the United Kingdom (UK).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The study by Marsden and colleagues used observational data from more than 15,000 prison releases in the UK among 12,260 individuals with opioid use disorder according to the prison electronic database for those who sought treatment. Authors collected data from September 2010 to October 2014 in 39 prisons that provided treatment as part of the Integrated Drug Treatment System, which included medication for opioid use disorder. Individuals volunteered to be prescribed medication or not, based on feedback from a clinical assessment and their preference. Officials attempted to link all individuals in the prison-based drug treatment with services post-release. Of note, all individuals in the prison system-based treatment program were included in the study unless they chose to “opt-out” – this is different than most longitudinal studies where individuals must consent to be included.

- MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Participants were categorized into one of two groups:

1) Medication “exposed” (i.e., Medication) if they were prescribed 20+ mg of methadone, or 2+ mg of Suboxone on the morning of their release

2) Medication “unexposed” (i.e., No medication)

Death for any reason (i.e., “all-cause mortality”) in the 4 weeks after release was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were drug overdose death (based on the coroner’s report and death certificate) in the 4 weeks after release, and death for any reason and drug overdose death during the period starting 4 weeks after release and end 1 year after release.

Participants were primarily male and 35 years of age, on average. As might be expected since individuals chose to receive medication or not (i.e., self-selection), and more help seeking is generally related to greater perceived severity/difficulty, in most cases the Medication group was significantly more severe including higher rates of injecting drugs (72% vs. 56%), benzodiazepine use (25% vs. 18%), and cocaine use (41% vs. 35%). For problem alcohol use, however, the Medication group had a significantly lower rate (29% vs. 36%).

In comparing the Medication and No Medication groups, authors adjusted statistically for several variables to try and isolate the comparison between the groups, and increase the confidence that receiving medication was causally related to the higher or lower death rates observed. These variables were: sex, age, drug injection use, problem alcohol use, benzodiazepine use, cocaine use, and having been transferred from one prison to another.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

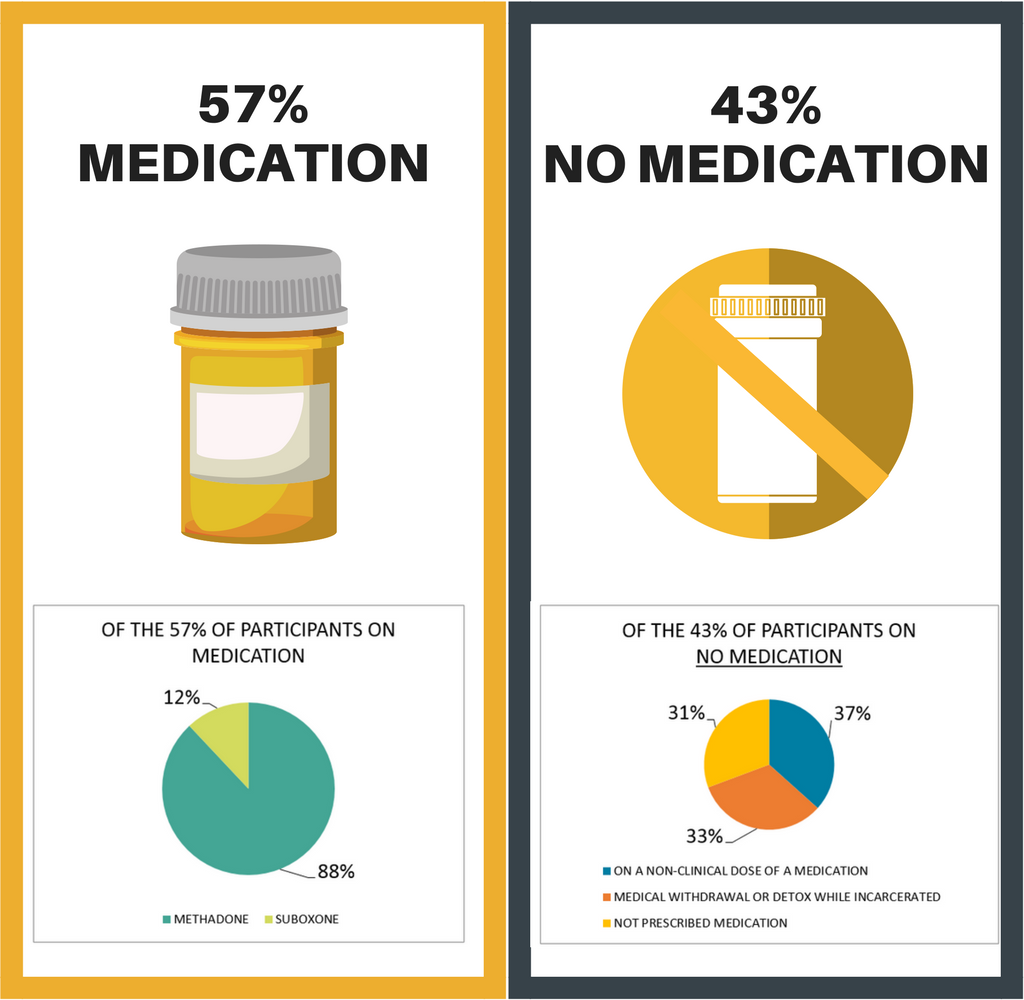

More than half were taking a medication on the day of their release. The pie chart below describes the treatment breakdown of the Medication vs. No Medication groups. For individuals in the Medication group, the median (i.e., average) methadone dose was 40mg and median Suboxone dose was 16mg.

In the first year after release, of the 12,260 individuals, there were 160 deaths (24 in the first month), 102 of which were drug overdose death (18 of which were in the first month). For the 24 deaths in the first month, 6 were in the Medication group and 18 in the No Medication group – after adjusting for other individual variables (e.g., history of injection drug use), the Medication group had a 75% lower likelihood of death. With respect to the 18 drug overdose deaths specifically, 3 were in the Medication group and 15 in the No Medication group – after adjusting for other variables as was done for all deaths, the Medication group had an 85% lower likelihood of drug overdose death.

There were other important findings in this study. First, the groups had similar rates of any death and drug overdose death after the first month, so it appears the benefits of receiving medication in prison may be most important in the first month but disappear over time. This is true even though the Medication group had 2.5 times greater odds of attending a treatment appointment in the month after release. In fact, attending treatment was unrelated to chance of death, and the benefits associated with receiving medication remained even when analyses adjusted for treatment attendance. This series of results indicates that benefits associated with receiving medication in prison on early death rates are probably not due to their greater likelihood of attending a community treatment appointment upon release.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT?

This real-world study of medications for opioid use disorder in the prison population in the UK showed that being prescribed methadone or Suboxone at clinically meaningful levels was associated with a substantially lower likelihood of death, including but not limited to drug overdose death, in the first month after release. These findings are critically important because prison systems in some other countries, including the United States, have traditionally been resistant to integrating opioid agonist medications like Suboxone and methadone into their drug treatment programs.

It seems, however, that the Medication group’s propensity to attend treatment after prison may be accounted for by their greater overall severity, which could make them more willing to engage in treatment. This treatment attendance did not reduce their likelihood of death during the year after release, though its effect on other outcomes (e.g., substance use, psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, employment, criminal recidivism) is unclear from this study. Also, receiving medication while in prison was not associated with reduced chance of death after the first month. While it is not clear what factors would lead to ongoing decreased risk of death, studies of medications for opioid use disorder over the long term suggest remaining on agonist medications like methadone or Suboxone are associated with better opioid outcomes and reduced overdose death risk based on dozens of well conducted studies.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The groups were not randomly assigned to receive medication for opioid use disorder. Therefore, the benefits of medication on reduced death rate cannot be entirely attributed to the medication itself. It may be, for example, that because the medication group was more severe, they were more motivated to change their substance use and other aspects of their lifestyle. That said, when all individual differences between the medication and non-medication group are considered together, it seems unlikely that the medication group had better outcomes because they had a more favorable prognosis, given that their history of injection drug use and benzodiazepine use would place them at greater risk for overdose.

- While authors were able to control for several individual factors, many psychological, social, and biological factors known to be risk and protective factors for substance use disorder outcomes (e.g., motivation, self-efficacy, family history of substance use disorder, environmental risks including drinkers and drug users in one’s social network) were not measured here.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps include conducting studies like these in other settings – namely in other countries outside the UK. If possible, studies should randomize individuals to a standardized medication protocol for methadone and/or Suboxone so that any differences between medication and non-medication groups can be attributed more fully to being prescribed medications. In a study conducted in the United States, individuals involved in the criminal justice system had better opioid outcomes when receiving the extended release injection form of naltrexone, known by brand name Vivitrol – however, these individuals did not take the medication while in prison, but rather while living in the community, making the sample an imperfect comparator to this study where individuals were taking medication while in prison. More research is needed on how to help individuals in the criminal justice system remain on medication, particularly during the first year of treatment, where risks for relapse and overdose remain quite elevated.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: For individuals with an opioid use disorder in jail or prison, receiving opioid agonist medications like methadone and Suboxone are likely to decrease your chances of overdose death and death more generally following release. This study took place in the United Kingdom, however, and countries differ in their integration of these medications in prison-based drug treatment programs.

- For scientists: This naturalistic evaluation of agonist medication for opioid use disorder in the United Kingdom prison system showed that, even after adjusting for several potential confounders, individuals choosing to receive agonist medication in prison had lower rates of all-cause mortality as well as drug overdose mortality in the first month post-release, compared to those whose treatment did not include medication. While more work is needed on the effects of both agonist and antagonist medication in criminal justice settings, given the large accumulation of evidence in the general population that agonist medications in particular help lower risk for overdose and death, it may be helpful to work with policy makers to integrate medications into prison-based drug treatment. In addition, future research might help determine what is needed to maintain the benefit of medication on overdose death beyond the first month post-release.

- For policy makers: This naturalistic evaluation of methadone and Suboxone for opioid use disorder (i.e., agonist medication) in the United Kingdom prison system showed that individuals receiving agonist medication in prison had lower rates of drug overdose death and death more generally, compared to those whose treatment did not include medication. While more work is needed on the effects of medication in criminal justice settings, given the large accumulation of evidence in the general population that agonist medications in particular help lower risk for overdose and death, it may be helpful to work with scientists to integrate medications into prison-based drug treatment using the evidence to inform decision making.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For clinicians working with individuals who have an opioid use disorder and are currently in jail/prison (or are part of the criminal justice system), receiving agonist medications like methadone and Suboxone are likely to decrease their chances of overdose death and death more generally following release from prison.

CITATIONS

Marsden, J., Stillwell, G., Jones, H., Metcalfe, C., Hickman, M., Cooper, A., & … Shaw, J. (n.d). Does exposure to opioid substitution treatment in prison reduce the risk of death after release? A national prospective observational study in England. Addiction, 112(8), 1408-1418.