Do pregnant women with opioid use disorder receive the standard of care while incarcerated?

Medication treatment with methadone or buprenorphine is the standard of care for pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD). Oftentimes, women admitted to prisons and jails are pregnant and have an OUD. In this study, authors examined OUD treatment policies at prisons and jails in the U.S., and whether incarcerated women with OUD received these empirically supported medicines.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) among pregnant women has increased more than fourfold from 1999 to 2014, and incarcerated pregnant women are more likely to have OUD than their non-incarcerated counterparts. Traditionally, pregnant women with OUD have been treated with methadone because withdrawal is associated with increased fetal morbidity, miscarriage, and recurrence of OUD symptoms. Current guidelines recommend that pregnant women with OUD are treated with opioid agonist pharmacotherapy with either methadone or buprenorphine, which are associated with better outcomes for the mother and the baby.

The criminal justice system in the United States, particularly correctional facilities, has been resistant to opioid agonist medications largely due to a misunderstanding of the difference between dependence and addiction (e.g., daily dosing with an opioid agonist medication like methadone can produce physiological “dependence” but it does not produce “addiction”, which often involves compulsive drug-seeking behavior, impaired control over use, and use despite harmful consequences) as well as concerns over diversion, despite evidence that shows these medications in incarceration settings improve outcomes. Correctional facilities are constitutionally mandated to provide health care, although there is no oversight or mandatory standards to ensure quality care. In this study, authors estimated the number of pregnant women with OUD admitted to prisons and jails, assessed how they were treated upon entry, and described institutional policies that address this population. Findings from this study show the extent to which the standard of care for pregnant women with OUD is aligned with the healthcare provided in criminal justice settings.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a cross-sectional survey of 22 prison systems and six large jails in the United States that assessed their institutional policies on medications for OUD for pregnant women. Authors also used data from the Pregnancy in Prison Statistics (PIPS) study, a six-month epidemiological surveillance study of pregnant women with OUD admitted to a subset of these correctional facilities that had the largest numbers of incarcerated individuals.

The institutional policy survey was conducted in 2016 with all 22 prisons and six jails that participated in the broader PIPS study responding with information on policies and procedures related to how pregnant women with OUD are managed at the facility. Specifically, the survey asked about pregnancy testing upon admittance, initiation and continuation of OUD medications, types of OUD medications provided, detoxification practices, availability of OUD medications to non-pregnant women, and if the facility is accredited or has privatized its healthcare.

The epidemiological surveillance study was conducted over six months in 2016-2017 as a voluntary supplement to the PIPS study. Twenty prison systems (representing 38% of incarcerated females in the United States) and four jails chose to participate by providing monthly reporting on the number of pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) admitted to the facility and how they were treated. Each site had a designated person that reported the number of pregnant women newly admitted and in custody with OUD, if these women underwent detoxification, if these women initiated or continued OUD medication, and, if so, what type of medication was administered. Screening for OUD varied by facility, with some making this determination using urine drug tests and others using self-report. Data from the surveillance study was aggregated and de-identified, meaning that there were no demographics, birth outcomes, site-specific outcomes, or post-incarceration outcomes associated with the individuals.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Most prisons and jails offered medications for opioid use disorder (OUD); but only if a pregnant woman was previously on these medications.

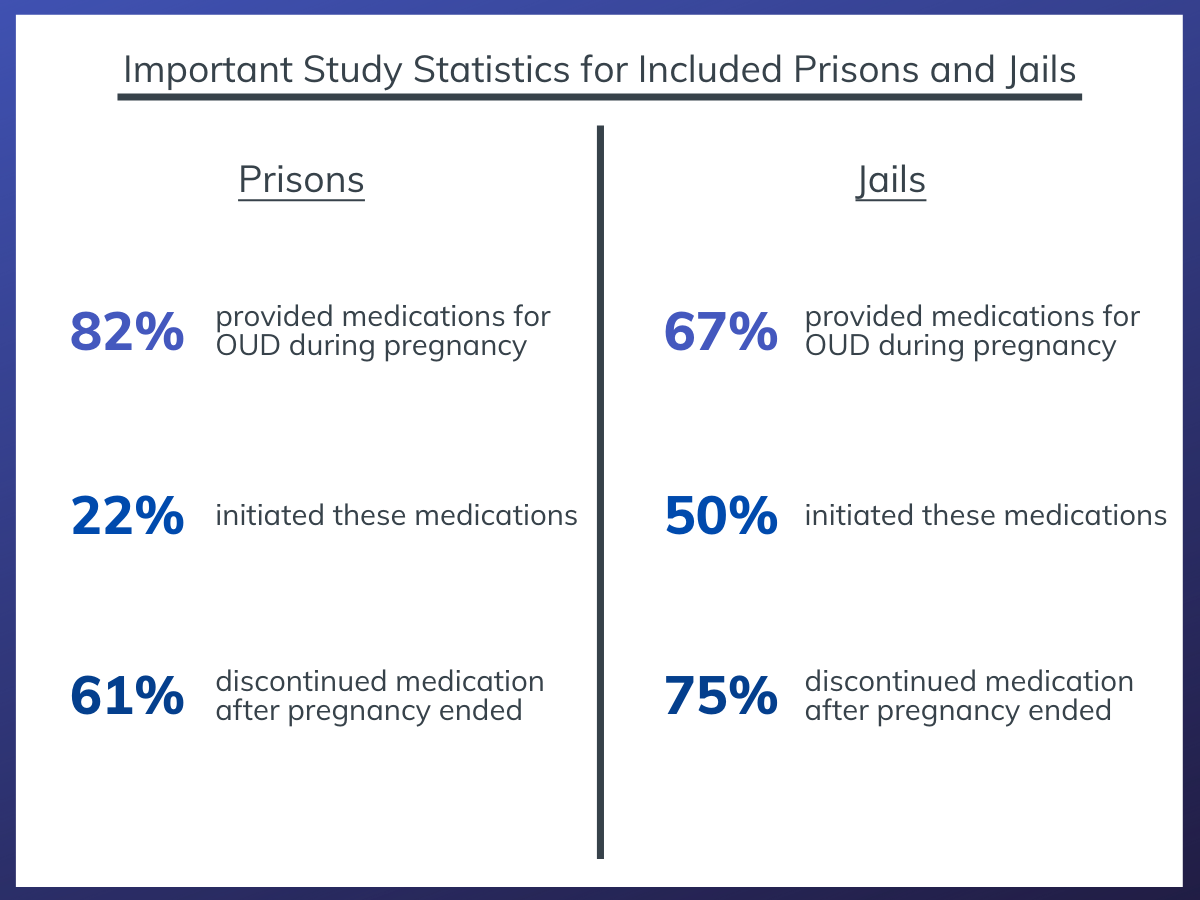

Overall, 82% of prisons and 67% of jails provided medications for OUD in pregnancy. However, only 22% of prisons and 50% of jails initiated these medications. In other words, the majority of correctional facilities required that a pregnant woman with OUD be on medication for this condition before they entered the facility in order for them to be continued on the medication. The predominant form of OUD medication used was methadone and, of the facilities that offered OUD medications, 26% of prisons and 75% of jails offered both methadone and buprenorphine.

Most prisons and jails discontinued OUD medications after pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Of the correctional facilities that offered medications for OUD, 61% of prisons and 75% of jails discontinued the medication after the pregnancy ended. Only 18% of prisons and 17% of jails made OUD medications available to non-pregnant women.

More than one-third of pregnant women with OUD were managed by opioid withdrawal.

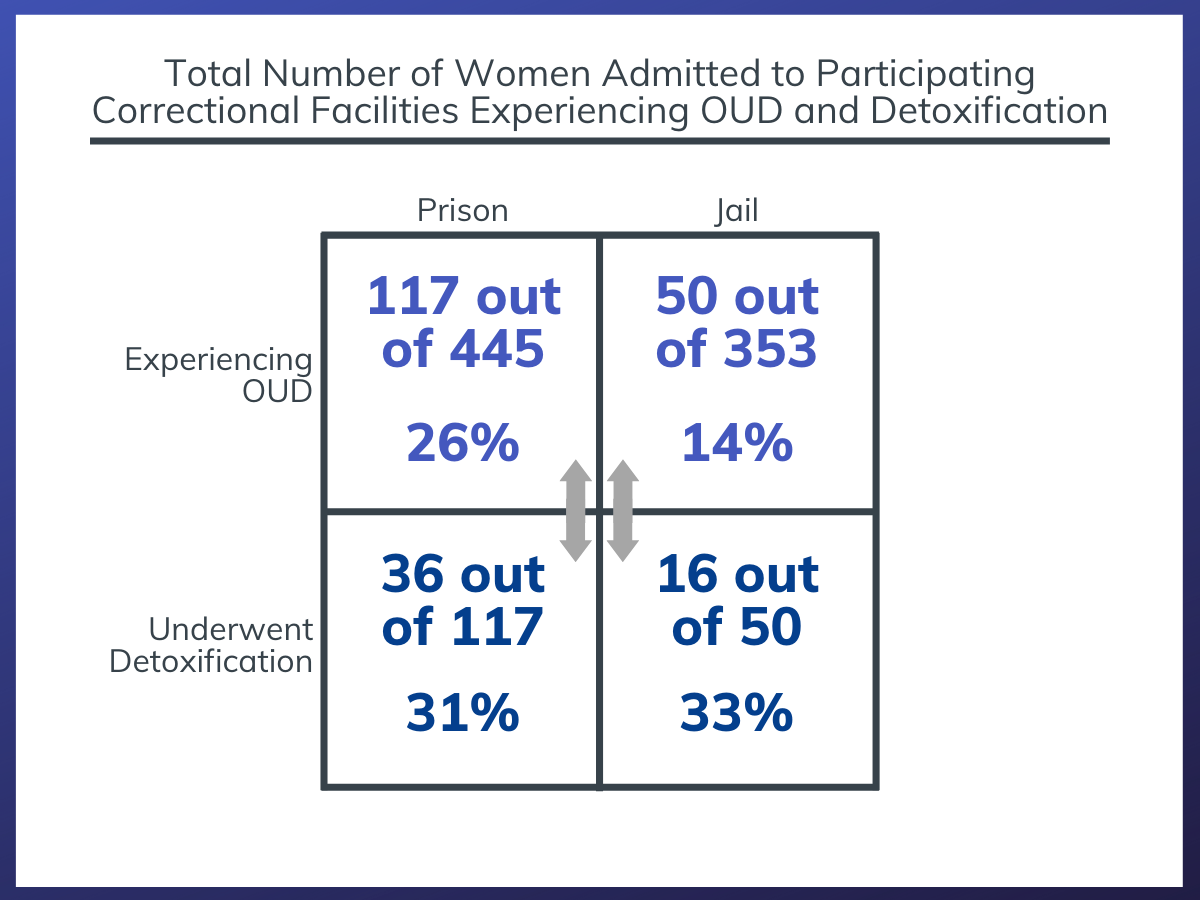

Four hundred forty-five pregnant women were admitted to participating prison systems during the six months of the surveillance study, with 117 (26%) being reported as having an OUD. Three hundred fifty-three pregnant women were admitted to participating jails, with 50 (14%) being reported as having an OUD. One-third (31%) of pregnant women with OUD admitted to prisons underwent detoxification, with 14% of these women undergoing opioid withdrawal without supportive medications. A similar percentage admitted to jails (33%) went through detoxification. Of those who were started or continued on OUD medications, 79% were on methadone and 21% were on buprenorphine.

Figure 2. The total number of women admitted to participating prison systems during the study period, the percentage who were experiencing OUD, and the percentage of them who went through detoxification.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Figure 3.

This study showed that, while most prisons and jails offer opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as an option to pregnant women with OUD, the majority require that the individual already be on the medication prior to incarceration in order to receive it while in prison or jail. In addition, the majority of prisons and jails in the study discontinued OUD medication after the pregnancy ended. Nearly one-third of study participants did not receive the correct clinical standard of care, instead being managed by medically supervised withdrawal (i.e. detoxification).

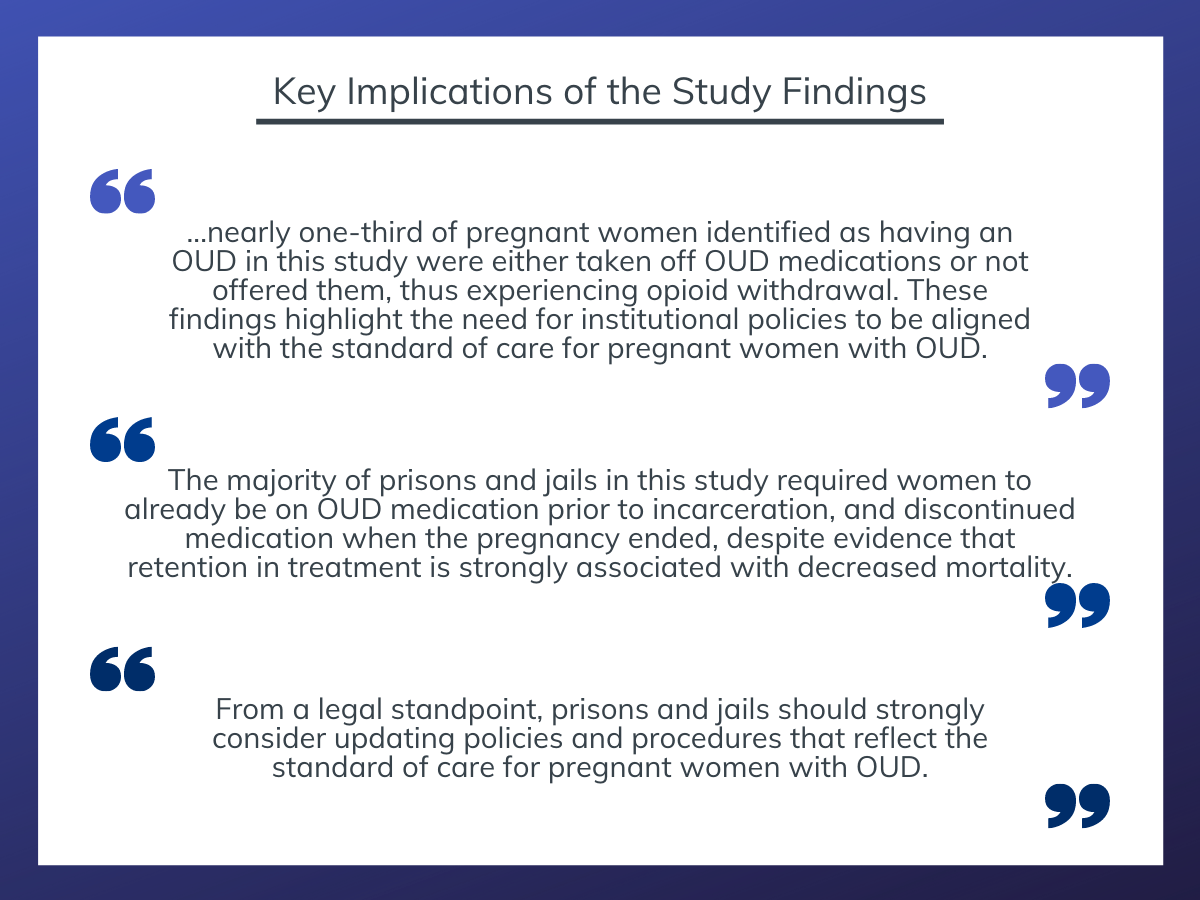

It is concerning that, despite the established, evidence-based standard of care of continuing opioid agonist pharmacotherapy and the recommendations against opioid withdrawal in pregnancy, not all prisons and jails in this study provided this treatment modality. In fact, nearly one-third of pregnant women identified as having an OUD in this study were either taken off OUD medications or not offered them, thus experiencing opioid withdrawal. These findings highlight the need for institutional policies to be aligned with the standard of care for pregnant women with OUD.

The majority of prisons and jails in this study required women to already be on OUD medication prior to incarceration, and discontinued OUD medication when the pregnancy ended, despite evidence that retention in treatment is strongly associated with decreased mortality. Treatment for OUD in the general population is already low as only 20% of those with OUD receive any treatment and only a third of these treated individuals receive medication. Post-incarceration overdose risk is extremely high and pregnant women with OUD are at greatest risk for overdose in the postpartum period.

Taken together, these data suggest that OUD medication should be initiated, not just continued, in correctional facilities and should not end after pregnancy.

The criminal justice system offers a vital touchpoint to initiate OUD medications for a high-risk population with this medical condition. Linkages to OUD medication upon release, along with psychological and social services, are highly likely to enhance outcomes for the mother and the baby. Policies and procedures that deliver this system of care will reflect person-centered treatment that prioritizes the well-being of the pregnant women, whereas a pregnancy-only approach to OUD medications prioritizes the well-being of the fetus.

The type of OUD medication that most pregnant women in this study used was methadone, which has traditionally been the standard of care for this population. However, buprenorphine has shown similar effectiveness while decreasing the chance for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), an expensive consequence of opioid dependence in pregnancy. In addition, the risk of NAS has been shown to be similar on both high and low doses of buprenorphine. There are also fewer regulations that impede implementation of buprenorphine in a criminal justice setting, and continuation of buprenorphine post-incarceration may be a better option due to decreased burden on the individual (i.e. buprenorphine can be prescribed by a doctor whereas methadone is only distributed at licensed opioid treatment providers (OTP) which initially require daily visits to the OTP). Buprenorphine may be underutilized in correctional facilities. Furthermore, extended-release versions of buprenorphine (injectables and implants) have recently emerged and would decrease concerns about diversion in this setting. Importantly, treatment should be individualized as more severe cases may respond better to methadone.

Due to the nature of the study, we are not sure whether the women who underwent detoxification wanted OUD medication but were denied this option by institutional policy and procedures or they were offered OUD medication but elected to decline it. Stigma and misunderstanding around these medications are pervasive, affecting individuals with OUD, providers that can prescribe OUD medications, and institutions that can facilitate access to OUD medications. For pregnant women, there is also a fear of their babies experiencing NAS. Clinicians treating pregnant women with OUD in criminal justice settings should engage in shared decision making and patient education with a realization of the power imbalance and decreased autonomy that define these settings. From a legal standpoint, prisons and jails should strongly consider updating policies and procedures that reflect the standard of care for pregnant women with OUD.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The policy survey took place in 2016 although the paper was published four years later. During this time period, there has been an increase in the utilization of medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) in prisons and jails. Survey findings may not accurately reflect the current policies of these correctional facilities towards pregnant women with OUD.

- Of the original sample that participated in the policy survey, two prison systems and two jails did not participate in the voluntary surveillance study. This likely led to selection bias meaning that the correctional facilities that chose to participate in the survey were likely more attuned to addressing pregnant women with OUD. The findings from this study, therefore, might overestimate how well prisons and jails were doing at the time with respect to providing OUD medications to pregnant women.

- Pregnant women admitted to the prisons and jails were not clinically diagnosed with OUD. Instead, they were screened for this condition, and how each institution made this determination varied.

- This study used de-identified aggregate data meaning that there were no demographics, birth outcomes, site-specific outcomes, or post-incarceration outcomes associated with the individuals in the surveillance study. Therefore, many important questions beyond the scope of the study remain unanswered. For instance, we are not sure whether women were offered OUD medication and refused or did not have the option of OUD medication.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study showed that, while most prisons and jails offer opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as an option to pregnant women with OUD, the majority require that the individual already be on the medication prior to incarceration. In addition, the majority of prisons and jails in the study discontinued OUD medication after the pregnancy ended. Nearly one-third of study participants did not receive the standard of care, instead being managed by withdrawal (i.e. detoxification). Medication treatment with methadone or buprenorphine for pregnant women with OUD is a well-established, evidence-based treatment modality that is considered the standard of care in this population. The postpartum period is a particularly dangerous time for women with OUD. Learn more about pregnancy, substance use, and recovery here.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study showed that, while most prisons and jails offer opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as an option to pregnant women with OUD, the majority require that the individual already be on the medication prior to incarceration. In addition, the majority of prisons and jails in the study discontinued OUD medication after the pregnancy ended. Nearly one-third of study participants did not receive the standard of care, instead being managed by withdrawal (i.e. detoxification). Comprehensive treatment for OUD during pregnancy offers a unique opportunity to deliver lifesaving, recovery-supportive interventions. Clinicians treating pregnant women with OUD in criminal justice settings should engage in shared decision making and patient education with a realization of the power imbalance and decreased autonomy that define incarceration settings. The type of medication selected should be individualized, but buprenorphine may be a good option based on existing data.

- For scientists: This study used a cross-sectional survey on institutional policies and procedures and an epidemiological surveillance study to show that, while most prisons and jails offer opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as an option to pregnant women with OUD, the majority require that the individual already be on the medication prior to incarceration. In addition, the majority of prisons and jails in the study discontinued OUD medication after the pregnancy ended. Nearly one-third of study participants did not receive the standard of care, instead being managed by withdrawal (i.e. detoxification). Aggregate de-identified data was used, so racial inequities, birth outcomes, or post-incarceration outcomes could not be assessed. Also, for the women who underwent detoxification, it is unclear whether they chose not to use OUD medication or were not provided with this option. Future studies should explore these research questions along with studying institutional barriers for not providing medication treatment to pregnant women with OUD, and strategies to enhance post-partum outcomes given the increased risk for overdose associated with this time period.

- For policy makers: This study showed that, while most prisons and jails offer opioid use disorder (OUD) medications as an option to pregnant women with OUD, the majority require that the individual already be on the medication prior to incarceration. In addition, the majority of prisons and jails in the study discontinued OUD medication after the pregnancy ended. Nearly one-third of study participants did not receive the standard of care, instead being managed by withdrawal (i.e. detoxification). As methadone and buprenorphine have been established as the most effective treatment for OUD in pregnant women, there may be legal ramifications to not providing this standard of care in these settings. The criminal justice system is a vital touchpoint to increasing utilization of OUD medications among a population that is disproportionately impacted by severe OUD. Wraparound reentry services, such as housing and employment support, should also be strongly considered to decrease recidivism and improve individual outcomes. This type of comprehensive, evidence-based treatment for a marginalized population has the potential to reduce health and racial-ethnic inequities and promote social justice.

CITATIONS

Sufrin, C., Sutherland, L., Beal, L., Terplan, M., Latkin, C., & Clarke, J.G. (2020). Opioid use disorder incidence and treatment among incarcerated pregnant women in the United States: results from a national surveillance study Addiction, [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/add.15030.