Are people with opioid use disorder interested in an innovative treatment option?

Opioid-involved overdose deaths are continuing to rise. A substantial proportion of individuals with opioid use disorder do not receive treatment and, for those that do, retention in treatment is low for those on medications for opioid use disorder with many still using illicit opioids. Innovative approaches are needed to address the opioid crisis. Injectable opioid agonist treatment (e.g., supervised injections of pharmaceutical substances similar to heroin) may be one such approach. In this study, researchers explored the perceptions of injectable opioid agonist treatment among people who regularly use opioids.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Despite expanding medications for opioid use disorder and increasing access to harm reduction services, overdose death rates continue to rise in the United States. Only 20% of individuals with opioid use disorder receive any treatment and only a third of these treated individuals receive medications, considered first line treatment for this disorder. In addition, although retention in treatment is higher for those on medications, in general, retention is still low and many continue to use illicit opioids. Taken together, these data suggest that more innovative strategies and treatment modalities are needed to increase initiation and engagement in treatment for those with opioid use disorder, especially in the context of a dangerous and uncertain illicit drug supply due to the emergence of synthetic opioids.

For those who have a severe opioid use disorder, prolonged history of injection heroin use, and unsuccessful opioid agonist treatment episodes with methadone (i.e., treatment refractory), injectable opioid agonist treatment is an available option in Canada and some European countries. Different from the harm reduction strategy of safe injection facilities where a person brings an illicit drug into the facility and is monitored for overdose, injectable opioid agonist treatment is a modality where the opioid is prescribed, and the person injects the drug under medical supervision typically 2-3 times per day. For those that are treatment refractory, this approach has demonstrated reductions in illicit heroin use and increased retention in treatment. However, it is considered a second line treatment with many restrictions for eligibility. In this study, researchers explored attitudes and preferences towards this approach among those who regularly use opioids and report lifetime history of injection drug use in Australia (a country that does not have access to injectable opioid agonist treatment), with a specific focus on participants’ interest in this approach and eligibility for it based on previous criteria. Understanding preferences may inform efforts to expand treatment engagement using the approach in the future.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In this study researchers conducted a cross-sectional survey of 344 people who reported regularly using opioids and a lifetime history of injection drug use in three cities in Australia to examine perceptions of supervised injectable opioid agonist treatment, focusing on interest in it, correlates of interest, reasons and preferences for interest/non-interest, and eligibility for the treatment based on criteria defined by researchers. This study adds to similar previous work among individuals participating in clinical trials by targeting a broader sample recruited from community-based organizations and drug treatment services.

The sample used in this study was derived from a previous study that examined perceptions of injectable extended-release buprenorphine and was limited to only those in the initial sample who reported lifetime injection drug use (n = 344).

Participants were recruited from a supervised injection facility, syringe service programs, drug treatment services, and through snowball sampling (i.e., existing study subjects recruit future subjects from among their acquaintances) in three Australian cities in three Australian states (Sydney, New South Wales; Melbourne, Victoria; Hobart, Tasmania). Interested participants were screened over the telephone and offered a small financial incentive to participate in the study. The survey was administered through a face-to-face interview and was conducted between December 2017 and March 2018.

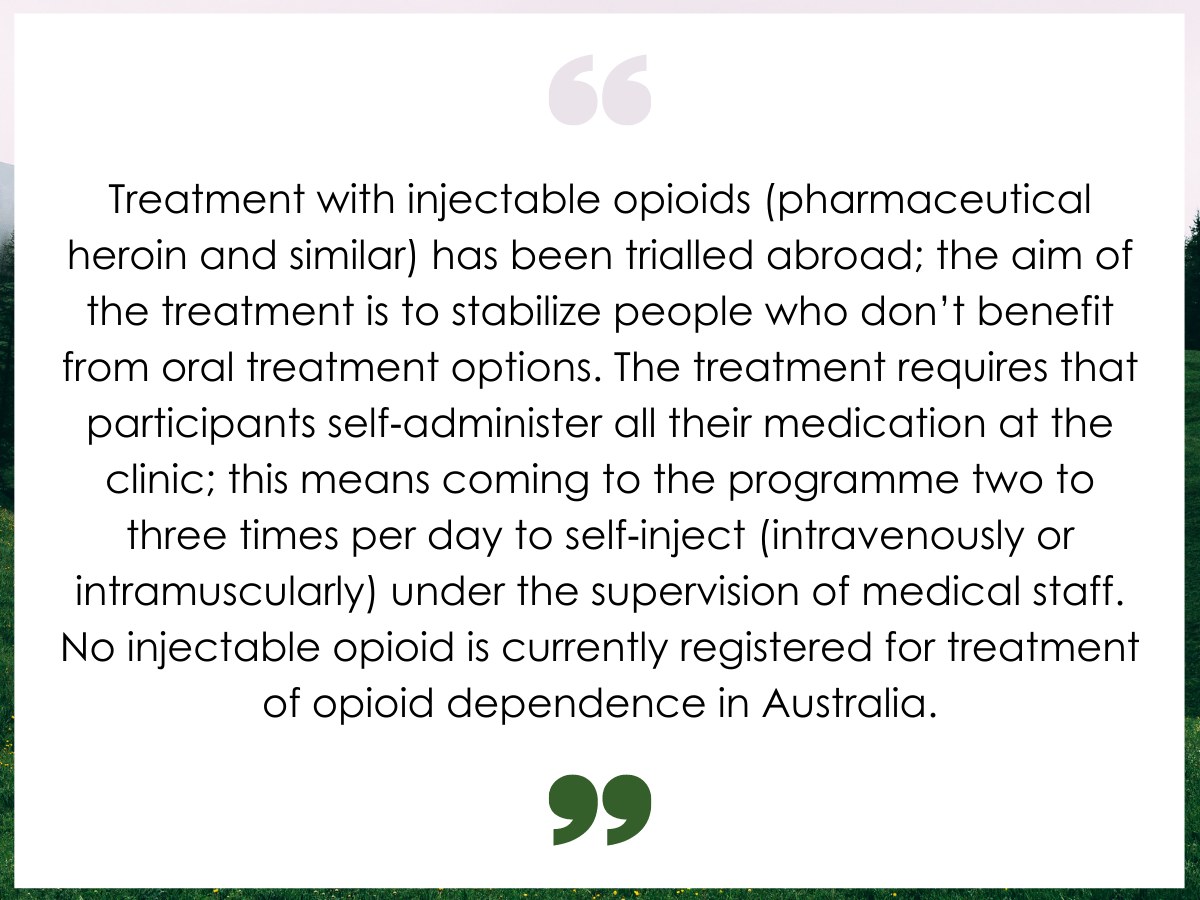

Figure 1. Participants were asked to read a vignette describing injectable opioid agonist treatment.

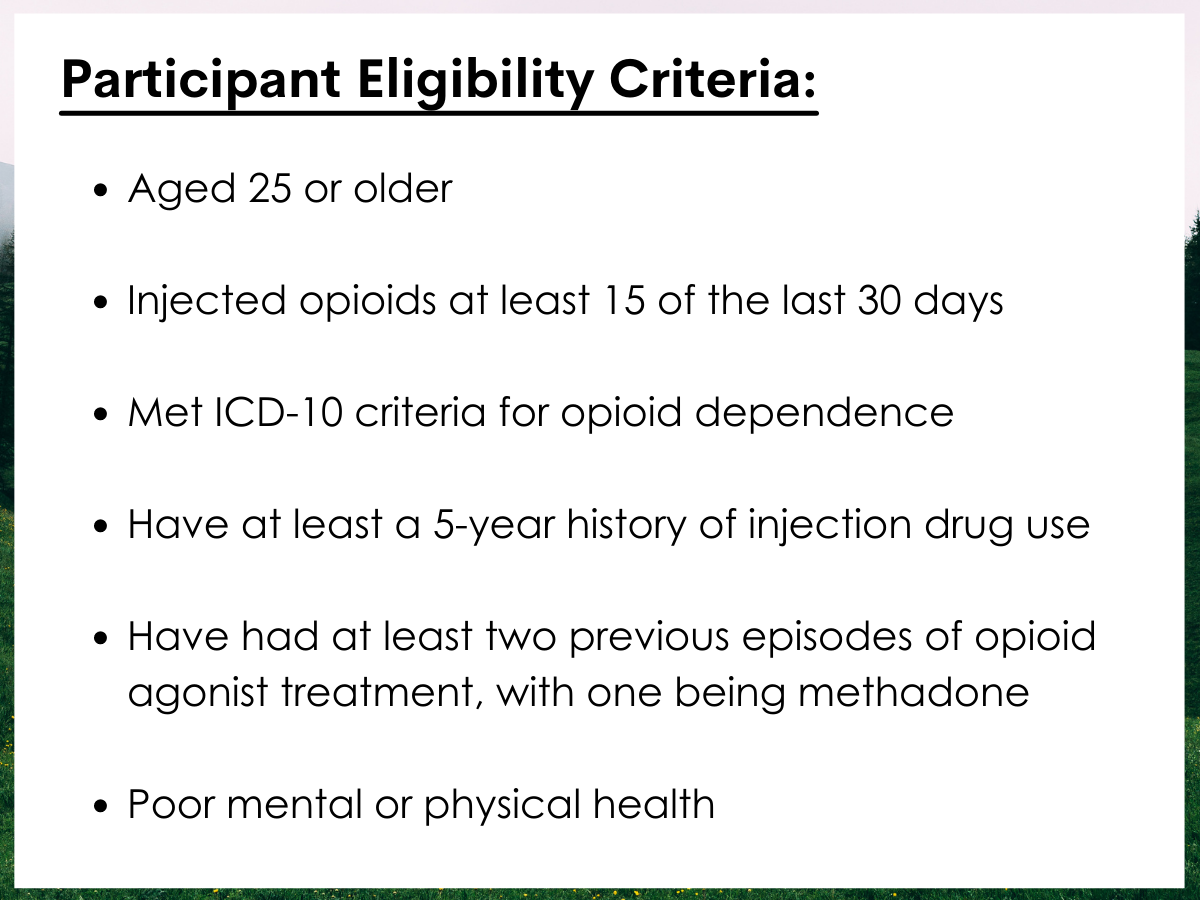

To gauge interest in injectable opioid agonist treatment, study participants read a vignette that described this treatment option. They were then asked if they would be interested in the treatment approach. Participants were also asked about medication and travel preferences, reasons for interest/non-interest in the injectable opioid agonist treatment, and perceptions on who should be offered it. Notably, participants picked from a list of options that was not mutually exclusive (i.e., they could choose more than one) rather than responding to open-ended questions from the interviewer. Other information collected from participants included measures of depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), physical health (EQ-5D-5L), substance use and treatment history, and opioid dependence (CIDI). The researchers combined commonalities from European and Canadian guidelines for the injectable opioid agonist treatment as well as documented eligibility criteria from several clinical trials to come up with a consensus set of eligibility criteria, which included:

Figure 2.

Additional exclusion criteria included frequent benzodiazepine use (use on at least 20 of the past 28 days) and hazardous alcohol consumption (a score of 4 or greater for males and 3 or greater for females on the AUDIT-C). These are considered exclusion criteria in some cases because of the medical risk of combining multiple central nervous system depressants (e.g., opioids and alcohol).

In addition to descriptive statistics, other statistical procedures were used to identify correlates of being interested in the treatment, controlling for age, gender, and Australian state. Meeting eligibility criteria was categorized by those that were interested and the treatment approach and those that were not interested. Even though there was a minimal amount of missing data, rather than not include these people in the analysis, statistical modeling was used to reduce potential bias from any missing data.

The sample analyzed in this study had a mean age of 41.5 years and was predominantly male (64%), met criteria for moderate to severe depression (57%), and had poor physical health (50%), and a slight minority met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (45%). Only 9% reported paid employment, 30% reported current homelessness, and 39% reported criminal activity in the past year. Regarding substance use, most participants reported past month heroin (66%) and methamphetamine use (54%), met criteria for opioid dependence (87%), had injected opioids in the past 12 months (94%), had injected opioids in 14 of the last 28 days (52%), and reported that it had been more than 5 years since first injection (97%). Regarding treatment history, most study participants were currently receiving opioid agonist treatment (55% on methadone and 11% on buprenorphine), had an average treatment duration on the medications of 2 years, and reported an average of 3 previous treatment episodes.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

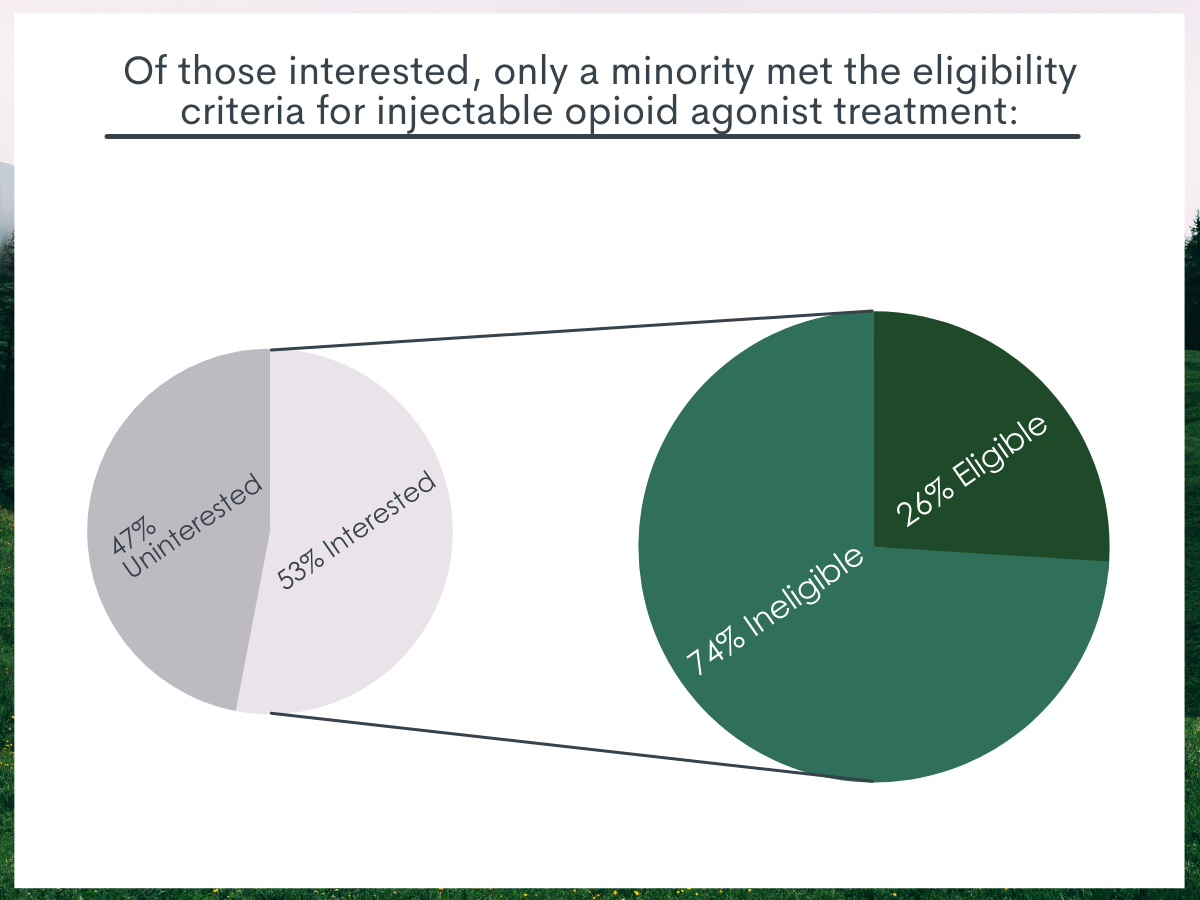

About half of study participants were interested in injectable opioid agonist treatment although only a minority met eligibility criteria.

After reading the vignette describing injectable opioid agonist treatment, 53% reported being interested in this treatment option. However, among those interested, only 26% met eligibility criteria. When additional exclusion criteria were applied regarding frequent benzodiazepine use and hazardous alcohol use, only 9% of those interested met eligibility criteria.

Figure 3.

Those interested in injectable opioid agonist treatment reflected a higher-risk population.

The odds of being interested in this treatment approach were 1.8 times higher for males, 1.6 times higher for those having moderate to severe depression, 10.9 times higher for those who reported injecting opioids in the past 12 months, 1.8 times higher for those who reported regularly injecting opioids in the past 28 days, 6 times higher for those who reported past month heroin use, and 3 times higher for those who met criteria for opioid dependence. Also, those interested had more previous treatment episodes. In contrast, the likelihood of being interested in the injectable opioid agonist treatment was lower for those who were currently in opioid agonist treatment, especially for those on buprenorphine.

There was variation in willingness to travel and most preferred treatment solely with an injectable substance similar to heroin.

Among those interested in this treatment approach, there was a wide variation in willingness to travel. Whereas 38% were willing to travel a total of 30 minutes or less to administer injectable medication 2-3 times per day under medical supervision, another 22% would have been willing to travel more than 90 minutes. A majority (69%) of those who were interested solely preferred an injectable opioid similar to heroin, not reflective of the current standard of care which typically includes an oral medication at night to prevent opioid withdrawal.

Reasons for interest in injectable opioid agonist treatment were primarily therapeutic.

Among those interested, their stated reasons aligned with its demonstrated benefits of decreasing illicit opioid use, improving health, and reducing criminality. Given a list of potential options provided by the research team and the ability to pick 1 or more of these options, 44% said that the injection treatment would help them stay off other opioids, 42% said that it would allow them to inject opioids in a healthier way, 40% said it would help them stay off injecting illicit drugs, and 40% said it would allow them to avoid trouble with the police. In contrast, only 19% – the least commonly selected reason for interest – said that it would provide them with a high that other medications do not.

Reasons for not being interested in injectable opioid agonist treatment were related to a rigid delivery system.

Among those not interested, stated reasons for not being interested had to do with the structure of how the treatment is delivered. Given a list of potential options provided by the research team and the ability to pick 1 or more of these options, 40% did not like the idea of coming to a clinic more than once a day, 30% felt like there would be less flexibility in their treatment, 24% were concerned that they could not get off injectable medication in the long run, and 19% said that it would not allow them to travel for work or holiday.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this cross-sectional survey of 344 people who regularly use opioids and have a history of injection drug use, approximately half believed that injectable opioid agonist treatment would be a good treatment option for them, though only 1 in 4 would meet eligibility criteria for this treatment modality and only 1 in 10 after excluding those based on frequent use of depressant drugs (benzos, alcohol). Those interested in this approach reflected a higher-risk population, and reasons for being interested were largely therapeutic; reasons for non-interest centered on the rigid structure of delivering the treatment.

Innovative approaches to address opioid use disorder are needed to reduce harms and improve outcomes. The treatment gap for people with the disorder – in the U.S. estimated to be roughly 80% of those who have it but do not receive treatment – cannot be entirely explained by lack of access to medications, such as methadone and buprenorphine. Some people are resistant or reluctant to engage with this treatment option. Others are not retained in traditional agonist opioid treatments or continue to use illicit opioids while in treatment. Injectable opioid agonist treatment, usually with diamorphine (also known as heroin) or hydromorphone (also known as Diluadid), may be a second line treatment option for those who have a severe opioid use disorder, have a long history of injection heroin use, and had an unsuccessful episode of opioid agonist treatment with methadone (i.e., treatment refractory). For those that are treatment refractory, this approach has demonstrated reductions in illicit heroin use, increased retention in treatment, and reduced criminality.

Among those interested in injectable opioid agonist treatment, the stated reasons for this interest were primarily therapeutic. Motivations were aligned with its demonstrated benefits, such as reducing illicit opioid use, improving health, and reducing contact with law enforcement. Despite this being a potentially controversial treatment option, the least stated reason among participants for using it was that it would allow them to be to obtain a high that other medications would not provide. Even so, delivery of this treatment option is highly structured and takes place under medical supervision.

This highly structured delivery of care was the most cited reason among study participants for not being interested, which consisted of nearly half the study sample. Among those interested, there was a wide variation in willingness to travel and medication preferences did not align with the current standard of care. These findings highlight both the need for a menu of options to treat opioid use disorder and the importance of person-centered care, which could increase treatment utilization. For instance, study participants who were not interested in this approach and preferred autonomy and flexibility in their treatment may be candidates for injectable extended-release buprenorphine. Clinicians can engage in shared decision making with their patients to facilitate this matching of individual characteristics with medication formulations. Integration of peer support into this shared decision-making process could strengthen the trust between patient and provider, further improving treatment outcomes.

Even though this sample may not represent those with opioid use disorder in general, nor the population with opioid use disorder in the United States or other countries, findings may provide an initial estimate for the demand for a treatment option like this. These findings also show that strict eligibility criteria will likely exclude many people who are interested in this treatment approach, as only 26% of those who were interested were eligible with the most common reasons for ineligibility being insufficient frequency of current injection opioid use and insufficient history of prior opioid agonist treatment attempts. Future studies should use more representative samples from the community to quantify probable treatment demand and better understand people’s preferences and perceptions of this approach. Future research and monitoring may also inform broadening the eligibility criteria for it to increase treatment utilization among those with treatment refractory opioid use disorder.

Stigma and misunderstanding around opioid agonist treatments such as methadone, and to a lesser degree buprenorphine, are pervasive, with many believing that this treatment option is “substituting one addiction for another.” An injectable opioid, such as heroin, is likely to have even more stigma associated with its adoption as a treatment option. Consequently, introducing an innovative approach like this is likely to be more successful if system-wide interventions to address negative attitudes are developed pre-emptively.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Caution should be taken in generalizing these findings as this study used a convenience sample of people in three cities in Australia where information on ineligible participants was unavailable, and those without access to a telephone and those from rural areas were not represented.

- This was a hypothetical scenario where participants were unlikely to have any real-world experience to inform their preferences.

- Study participants read a vignette that described injectable opioid agonist treatment. Depending on the language used in this vignette, different assumptions may be made, as has been shown in other studies.

- The criteria used to determine if study participants were eligible for injectable opioid agonist treatment was primarily drawn from commonalities in clinical trials and guidelines, which may be more restrictive than criteria used in clinical practice.

- The survey taken by study participants was administered using a face-to-face interview and asked individuals to recall events in the past, possibly making the ultimate findings vulnerable to some degree of social desirability bias and recall bias.

BOTTOM LINE

In this cross-sectional survey among 344 people who regularly use opioids and have a history of injection drug use, approximately half believed that injectable opioid agonist treatment would be a good treatment option for them, though only 1 in 4 would meet eligibility criteria for this approach. Those interested reflected a higher-risk population, and reasons for being interested were largely therapeutic whereas reasons for non-interest were primarily related to the rigid structure of delivering the treatment.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: For many people, opioid use disorder is a chronic, relapsing disorder that may take several treatment attempts to achieve remission and responds best to medication. Yet even these medications are unable to keep the majority of those suffering engaged in treatment. Severe opioid use disorders that have not responded to a variety of medication treatment modalities (e.g., buprenorphine, methadone) may benefit from injectable opioid agonist treatment, which has been shown to improve outcomes for this high-risk population.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: For many people, opioid use disorder is a chronic, relapsing disorder that may take several treatment attempts to achieve remission and responds best to medication. Yet even these medications produce relatively low treatment retention. Severe opioid use disorders that have not responded to a variety of treatment modalities may benefit from injectable opioid agonist treatment, which has been shown to improve outcomes for this high-risk population. This study found that those interested in this treatment were motivated for therapeutic reasons, potentially mitigating the concern of patients choosing this treatment option merely to get “high” at taxpayers’ expense.

- For scientists: This study used a cross-sectional survey on a convenience sample and asked participants about a hypothetical scenario in which they were likely to have little to no experience to inform their attitudes and preferences. More representative studies are needed to quantify probable treatment demand and better understand people’s preferences and perceptions of injectable opioid agonist treatment. Findings highlighted a misalignment of preferences with the current delivery system for this approach, which may benefit from further exploration. Due to the limitations of studying this treatment using randomized control trials, other types of study designs may be needed to provide better estimates of relative effectiveness and clinical and public health impacts.

- For policy makers: Innovations are urgently needed to address the opioid crisis, where overdose deaths continue to rise, and the illicit drug supply remains dangerous and uncertain. Injectable opioid agonist treatment may be one these innovations, which has shown promising results in Canada and some European countries. This study found that perceptions of participants largely reflected policy where the approach is limited to those with more severe opioid use disorder and for whom other treatments had not worked. In addition, motivations to use this treatment option were primarily therapeutic and aligned with the demonstrated benefits of the approach.

CITATIONS

Nielsen, S., Sanfilippo, P., Belackova, V., Day, C., Silins, E., Lintzeris, N., . . . Larance, B. (2020). Perceptions of injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) among people who regularly use opioids in Australia: findings from a cross-sectional study in three Australian cities. Addiction, [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1111/add.15297