“Proceed with caution”: Replication study refutes causal relationship between medical marijuana laws and reduction in opioid overdose mortality rates

Medical marijuana has been touted as a solution to the U.S. opioid overdose crisis since a 2014 paper by Bachhuber et al. reported that from 1999 to 2010, states with medical marijuana laws experienced slower increases in opioid overdose deaths compared to states that didn’t have medical marijuana. This research received substantial attention in the scientific literature and popular press, and cannabis industry advocates then argued that individuals with opioid use disorder can use cannabis to reduce or stop opioid use. To inform key policies on the intersection between cannabis laws and opioid use, Shover and colleagues sought to replicate Bachhuber et al.’s original work, and, using the same methods, to extend the analysis through to 2017.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

There is a pressing need to examine any clinical and public health solutions that could potentially curb the current opioid public health crisis. Medical marijuana has been touted by some as a potential solution since Bachhuber and colleagues reported that from 1999 to 2010 states with medical marijuana laws experienced slower increases in opioid overdose deaths. That research received substantial attention in the scientific literature and popular press and served as a talking point for the cannabis industry and its advocates. This is in spite of caveats from the authors and others to exercise caution when interpreting the findings of this paper. In the study summarized here, Shover and colleagues sought to replicate Bachhuber et al.’s findings, and using the same methods, to extend the analysis through to 2017 to highlight the risk of using population level data to draw conclusions about individual responses to policies and interventions.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Opioid overdose deaths were identified in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER). Other variables including annual state unemployment rate (because unemployment is thought to hamper opioid use disorder recovery) and presence of prescription drug monitoring program (which can help reduce misuse of opioid medications), pain management clinic oversight laws (which can reduce over-prescribing of opioid medications), and laws requiring or allowing pharmacists to request patient identification were obtained from the sources cited in the original paper by Bachhuber and colleagues. The authors also reviewed the legal literature to assess the effects of potential inaccuracies in the data sources in the original paper. To assess the association between new cannabis laws implemented since 2010, Shover and colleagues created a model that included indicator variables for three kinds of cannabis laws: (i) presence of a recreational cannabis law and medical cannabis law, (ii) medical cannabis only with no restriction on THC content, and (iii) medical cannabis but only low-THC.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

For the original 1999–2010 time period, authors found a 21.1% decrease in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 individuals in the population associated with the introduction of medical marijuana laws. None of the other variables investigated in their statistical model (i.e., annual state unemployment rate, and presence of the following: prescription drug monitoring program, pain management clinic oversight laws, and law requiring or allowing pharmacists to request patient identification) were associated with opioid overdose death rate. These findings were similar to the original Bachhuber analysis.

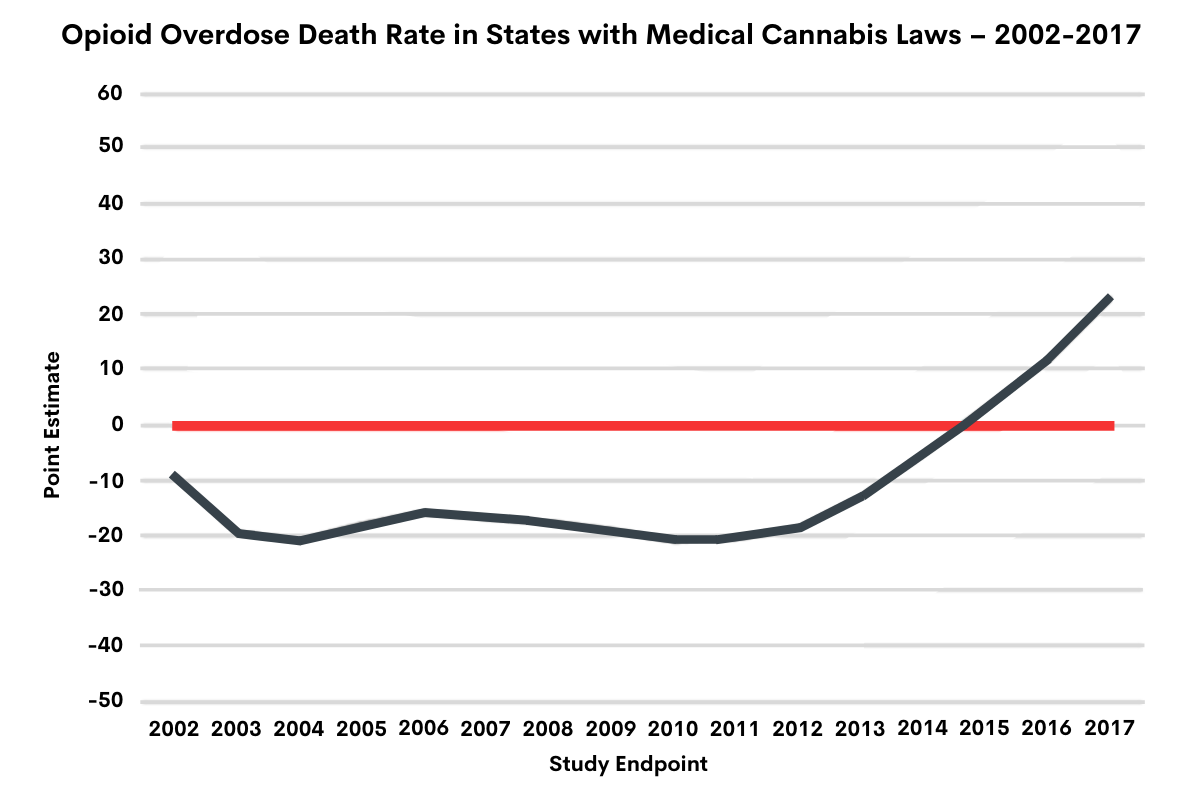

Interestingly however, using the full 1999-2017 dataset, the authors found that the direction of the effect reversed for medical marijuana laws, such that states passing a medical marijuana law experienced a 22.7% increase in overdose deaths.

Figure 1. Source: Shover, Davis, Gordon, & Humphreys, 2019. Changes in the direction of the association between medical marijuana laws and opioid overdose deaths from 2002-2017. From 2002-2004, the line trends downwards suggesting fewer opioid related deaths in states with medical marijuana laws. From 2005-2012, however, the line appears to flatten out, and then from 2013 onwards the line trends upwards, suggesting medical marijuana laws are associated with greater opioid overdose deaths. The authors highlight that this changing trend is most likely simply a result of random statistical variability one observes in this kind of population-level data. In other words, they suggest that the observed associations are most likely due to chance.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

As Shover and colleagues note, the mechanism theorized to describe a causal relationship between medical marijuana laws and opioid overdose deaths rests on several premises: (i) cannabis is more available in states with medical cannabis laws; (ii) people in these states substitute cannabis for opioids, whether for pain management, intoxication, or both; and (iii) this substitution occurs on a large enough scale to impact the population-level overdose mortality estimates. Under this model, states with highly restrictive medical cannabis laws limited to low-THC products would be expected to have a weaker association than states with comprehensive medical cannabis, while states with recreational cannabis would be expected to have a stronger association. The authors’ results do not support this, as after adjusting for more and less restrictive types of cannabis law (recreational and medical or low-THC only), states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws still had a positive association with opioid overdose deaths.

Taken together, the results of this reanalysis suggest broader access to cannabis associated with medical marijuana laws is not associated with lower opioid overdose death rates. Unmeasured variables likely explain any previously observed associations (e.g., state incarceration rates and practices, naloxone availability, and the availability of insurance and addiction treatment services). Also, people using medical marijuana are only about 2.5% of the population, making it unlikely that they can significantly alter population-wide measures. These findings also highlight the risk of falling into what is known as the ecological fallacy, a failure in reasoning that arises when an inference is made about an individual based on aggregate data for a group. Finally, these results highlight the necessity of being more systematic about testing causal relationships when using research to inform public policy.

- LIMITATIONS

-

The limitations of this study are the same as Bachhuber and colleagues’ original study:

- Causal inferences cannot be made based on this kind of population-level data.

- Even if an association is observed between two measures, one cannot make assumptions about individual’s behavior based on population-level trends.

- Additionally, in these kinds of replication analyses, authors are restricted by available data. In other words, they are limited in the type of research questions they can answer.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: A study published in 2014 showed an association between medical marijuana laws and reduced overdose deaths that informed policy and public discourse. In light of the possibility that these population level correlations were being inappropriately applied to individual behavior, the authors of the current study tested and found that when extended further, medical marijuana laws were statistically associated with increases in overdose. This doesn’t mean that marijuana laws are causing overdose, but rather it highlights that these findings are probably a function of statistical chance, and other complex factors. More rigorous research focused on individual behavior is needed to inform cannabis policy, especially as it pertains to the current opioid crisis. The authors also highlight interpretation errors made by individuals who cited the original paper as evidence that medical marijuana prevents opioid deaths. This paper is a reminder to be wary of buying into rhetoric, especially on highly charged debates like medical marijuana. Based on Shover and colleagues’ findings, as yet there is no reliable or convincing evidence suggesting medical marijuana laws are related to opioid death rates.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: A study published in 2014 showed an association between medical marijuana laws and reduced overdose deaths that informed policy and public discourse. In light of the possibility that these population level correlations were being inappropriately applied to individual behavior, the authors of the current study tested and found that when extended further, medical marijuana laws were statistically associated with increases in overdose. Further, the authors found evidence suggesting Bachhuber and colleagues’ original study that showed an association between medical marijuana laws and opioid death rates was likely a result of normal variability over time and statistical chance. They also highlight misapplication of research findings by individuals who cited the original paper as evidence that medical marijuana prevents opioid deaths. This paper is a reminder to be wary of buying into rhetoric, especially on highly charged debates like medical marijuana. Based on Shover and colleagues’ findings, as yet there is no reliable or convincing evidence suggesting medical marijuana laws are related to opioid death rates.

- For scientists: A study published in 2014 showed an association between medical marijuana laws and reduced overdose deaths that informed policy and public discourse. In light of the possibility that these population level correlations were being inappropriately applied to individual behavior, the authors of the current study tested and found that when extended further, medical marijuana laws were statistically associated with increases in overdose. Further, the authors found evidence suggesting Bachhuber and colleagues’ original study that showed an association between medical marijuana laws and opioid death rates was a result of random variability and statistical chance. They also highlight misapplication of research findings by individuals who cited the original paper as evidence that medical marijuana prevents opioid deaths. This paper is a reminder to be wary of buying into rhetoric, especially on highly charged debates like medical marijuana. Although it is highly unlikely that medical marijuana laws influence opioid overdose death rates, there is a pressing need for research into factors that could actually potential be influencing opioid death rates such as availability of naloxone and buprenorphine (often prescribed in combination with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), criminal justice policy, and resources in the community that facilitate recovery from opioid use disorder.

- For policy makers: A study published in 2014 showed an association between medical marijuana laws and reduced overdose deaths that informed policy and public discourse. In light of the possibility that these population level correlations were being inappropriately applied to individual behavior, the authors of the current study tested and found that when extended further, medical marijuana laws were statistically associated with increases in overdose. The authors also found evidence suggesting Bachhuber and colleagues’ original study was a result of random variability and statistical chance and highlight the misapplication of research findings by individuals who cited the original paper as evidence that medical marijuana prevents opioid deaths. This paper is a reminder to be wary of buying into rhetoric, especially on highly charged debates like medical marijuana. It also is a reminder that correlation is not causation, and to be wary of falling into the ecological fallacy when interpreting population level findings. Specifically, the ecological fallacy is a failure in reasoning that arises when an inference is made about an individual based on aggregate data for a group. For these reasons, using epidemiological data to understand individual level behavior can lead to misapplication of research findings and policies that are not evidence-based despite best intentions. Current data does not support the use of medical marijuana to address the opioid crisis.

CITATIONS

Shover, C. L., Davis, C. S., Gordon, S. C., & Humphreys, K. (2019). Association between medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality has reversed over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A, 116(26), 12624-12626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116