Does drug court participation reduce mortality risk?

Criminal-justice involved individuals report high rates of substance use and are at an elevated risk of substance use-related mortality though research on the long-term effects of criminal justice interventions, such as drug courts, is limited. Drug court participation may involve alcohol and other drug treatment, drug testing, and case management, while individuals receiving usual court adjudication may still have access to these services, but without facilitation and oversight by the courts. In this study where individuals charged with non-violent drug offenses were randomly assigned to either drug treatment court or adjudication-as-usual, the research team found no difference in general or substance use-related mortality over a 15-year follow up period.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Opioid-involved overdose deaths are part of an ongoing public health crisis and are estimated to represent approximately two-thirds of all drug overdose deaths in the United States, which more than doubled between 1999 and 2014. Among those at an elevated risk for drug overdose deaths are formerly incarcerated individuals, who are over 4 times more likely than those without an incarceration history to die from a drug overdose.

Data from the Department of Justice estimate that between 2007 and 2009, nearly two-thirds (63%) of people in jails and over half (58%) of state prisoners met DSM-IV criteria for opioid and other drug use disorder, but only 22% and 28% of people in jails and prisons, respectively, participated in any type of drug treatment since admission. (Notably, however, these rates of treatment are higher than that of those in the general population). Researchers have also found that the leading cause of death among all prisoners following release from prison is related to drug use, particularly within the first two weeks after release.

Criminal justice involved individuals face unique challenges and barriers to accessing substance use disorder treatment. Researchers have therefore highlighted various intervention opportunities at multiple stages throughout the criminal justice process ranging from initial entry (arrest) to community reentry (probation, parole, or release). Drug courts are one such opportunity for intervention which offer people with substance use disorder an alternative option to incarceration, provided they agree to participate in treatment.

Previous research has focused on the effects of drug courts on recidivism. This research generally shows that those who participate in drug courts have lower rates of recidivism than those who do not participate in drug courts. Critical questions remain, however, about the impact of drug court participation on the lives of participants. In this study, researchers begin to address this evidence gap by examining the effect of drug treatment courts on long-term (15-year) mortality risk in a randomized trial.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a randomized controlled trial with 235 participants who were charged with non-violent drug offenses between 1997 and 1998 and assigned to either drug treatment court (n = 139) or adjudication as usual (referred to as “traditional adjudication” by the research team; n = 96) and followed for 15 years to assess long-term mortality risk.

Participants were adults with open cases in either District or Circuit Court in Baltimore who were in need of substance use disorder treatment (as assessed by the Addiction Severity Index) and who did not have a prior conviction of a violent offense.

Participants in the control condition underwent traditional adjudication but may have individually sought treatment for their substance use disorder or may have been required to participate in substance use disorder treatment as a condition of their probation. Researchers provided little additional information about the control condition.

Participants in the intervention condition – drug treatment court – were required to participate in some sort of substance use disorder treatment depending on their individual needs. There were four primary components of this drug treatment court including: Intensive probation supervision, drug testing, substance use disorder treatment, and judicial monitoring (see Figure 1 for details).

Figure 1. Four primary components of drug treatment court.

In cases of program non-compliance in drug treatment court, judges would provide various and increasingly severe sanctions ranging from more frequent status hearings, drug testing and curfew, to home detention or temporary incarceration. Severe non-compliance could result in the judge imposing the original sentence for the offense, which could end up being more severe than what would be imposed in adjudication as usual.

The two primary outcomes assessed in this study were 1) mortality and 2) substance use-related mortality. The research team assessed whether or not the participant died during the study follow-up period and if so, the number of years between the date of randomization and the date of death. Deaths were classified as substance use-related if the participants died from a drug overdose or poisoning, or from conditions where substance use is implicated as playing a significant role in the initial infection or disease progression (e.g., hepatitis, HIV, septicemia, etc.). Mortality rates were reported “per person year” – that is, the number of deaths in the sample divided by the total number of years the sample was followed (either until death or the end of the study’s 15-year follow-up period, whichever came first). The research team also reported participants’ demographics, number of prior arrests and convictions, and primary and secondary substance of choice.

Demographics, criminal justice involvement, and substance use disorder treatment data were obtained from the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services and the Baltimore Substance Abuse Systems, Inc., which coordinates substance use disorder services in Baltimore. Date and cause of death were obtained from the Maryland Vital Statistics Administration and the U.S. Social Security Death Index for the 15-year follow-up period.

The majority of participants in the study were male (74%), Black (89.4%), and approximately 35 years old at the time of randomization. The median number of prior arrests and convictions were 10.0 (range 0-55 arrests) and 4.0 (range 0-24 convictions), respectively.

The research team used an intent-to-treat approach, meaning that all participants who were randomized were included in the analyses, even if they did not receive the intervention to which they were assigned (e.g., drug treatment court) or were not followed up. Due to treatment waiting lists, some participants assigned to the intervention condition were re-arrested or found non-compliant before beginning treatment and therefore did not receive substance use disorder treatment.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Heroin was the primary (77.9%) or secondary (88.5%) substance of choice among study participants and rates of medication use for opioid use disorder (OUD) were low.

Data regarding participants’ substance of choice was only available for a subset of the sample (66.2% of drug treatment court and 31.3% of traditional adjudication participants) but suggested that 77.9% and 88.5% of participants reported heroin as their primary or secondary substance, respectively. The proportion of individuals in the intervention (89.1%) and control (86.7%) conditions who reported heroin as their primary or secondary substance of choice did not differ between groups. There was no difference in the use of medication for opioid use disorder (referred to as “methadone maintenance” in the study) between the intervention and control condition, which was used by less than 10% of participants in each condition.

Approximately 1 in 5 participants died during the follow up period.

Overall, 20.9% of participants (n = 49) in the study died in the 15 years following randomization, with the average age of death equaling 46.6 years old, and the median time to death following randomization equaling 5.2 years. Participants who were older at the time of randomization were at a higher risk of death due to any cause as well as due to substance use-related causes during the 15 year follow up. Researchers also found higher rates of substance use disorder deaths among individuals with a higher number of prior convictions at the time of randomization.

Approximately half of participants who died during the follow-up period died from substance use-related causes.

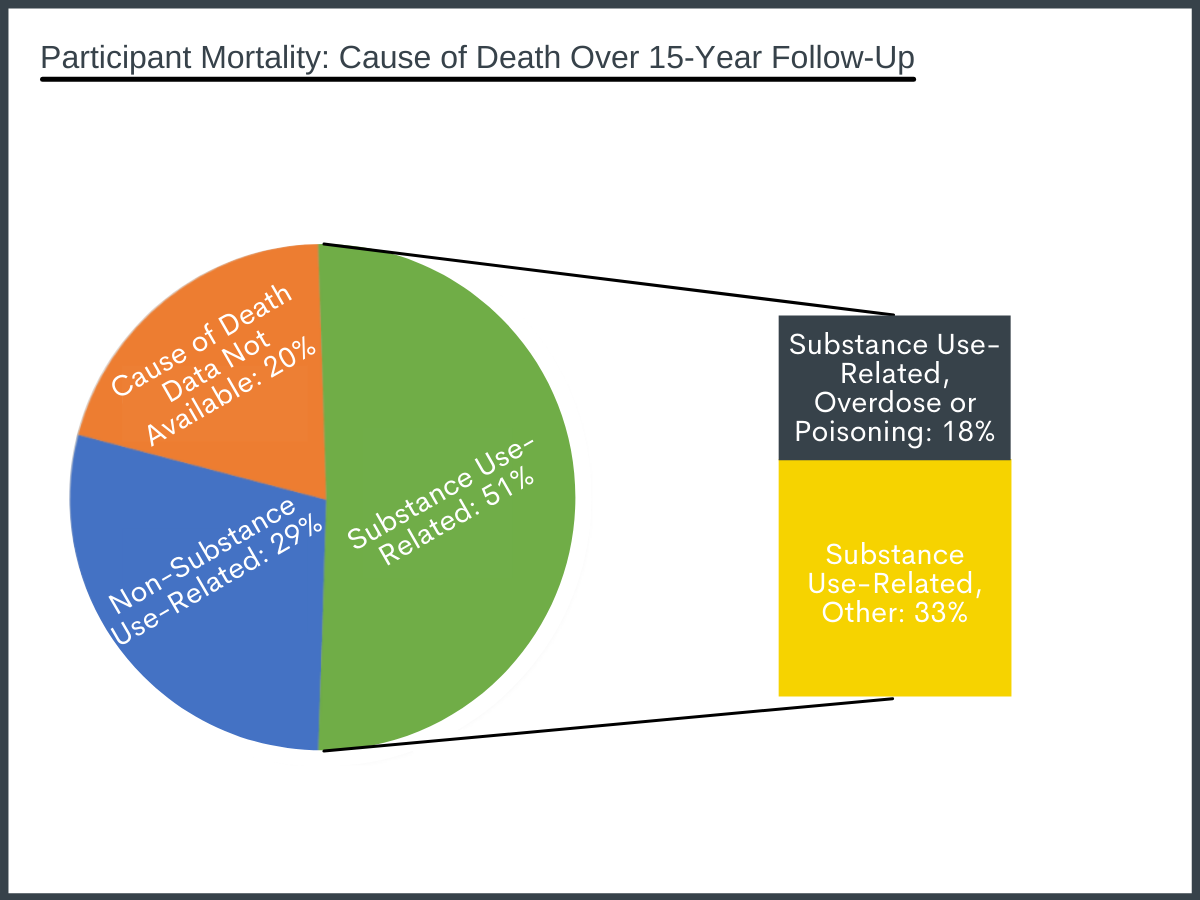

Cause of death data were available for 39 (79.6%) of the 49 participants who died during the follow-up period. Of the 39 participants for whom cause of death data were available, 25 participants (64%) died due to substance use-related causes. Approximately one third (36%) of substance use-related deaths were attributed to drug overdoses or poisoning, and 64% to substance use-related diseases.

Figure 2. Participant mortality: Causes of death for the n = 49 participants who died over 15-year follow up period.

Rates of death did not differ between the drug treatment court and adjudication as usual conditions.

Rates of death due to any cause did not differ between the drug treatment court (23.0%; 1.7 per person year) and adjudication as usual (17.7%; 1.3 per person year) groups when controlling for age. Similarly, there was no difference in rates of substance use-related death between the two study conditions when controlling for age and number of prior convictions. Notably, however, 12 participants for whom cause of death or count of prior conviction data were not available were excluded from the substance use-related mortality analyses.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Approximately one in five (20.9%) participants in this study died during the 15 years following randomization, with half of all deaths occurring within approximately 5 years following randomization. The participants who died during the follow up period were approximately 46 years old on average, which, according to the research team, is approximately 26 years shorter than the average life expectancy for Black men in the United States and for the general population in the city of Baltimore. This finding is consistent with what has been reported elsewhere, which is that formerly incarcerated individuals are a high-risk population at an elevated risk for mortality, including from overdose and other substance use-related causes of death.

The majority of participants in the sample reported heroin as their primary or secondary substance, but only a small minority (<10%) of participants in each group received medication for OUD (in this case, methadone). The FDA did not approve Buprenorphine for the treatment of OUD until 2002 and naloxone until 2010. Thus, at the time participants were enrolled in the present study (1997-1998), methadone was the only option for medication treatment for opioid use, and its use was not widespread in this sample.

Medication for opioid use disorder is known to be an effective treatment for opioid use disorder and is the strongest tool available to reduce opioid-involved overdose death. There may have been a reduction in substance use-related deaths in this study if a larger proportion of this predominately opioid-primary sample had used medications, including the newer medications available today.

Indeed, medication for opioid use disorder is effective for reducing risk of death from opioid use and is more widely used in drug courts today than when participants in this study participated in drug treatment court; however, it is still largely underutilized. In a national survey of availability of, and barriers to, medication for opioid use disorder in U.S. drug courts, responses from 93 courts across 47 states (as well as Washington DC and Puerto Rico) indicated that while 98% of courts serve individuals with opioid use disorder, only 47% offer methadone or buprenorphine, and only 56% offer methadone, buprenorphine or naloxone. In this particular national survey, medication costs and court policies were commonly cited barriers to drug treatment court participants having access to medication treatments. The authors specifically cited opposition to medication for opioid use disorder at the court administration, judicial and political levels as reasons why medications were not more widely available and accessible to drug court participants. Thus, an important component of efforts to reduce mortality among individuals in drug treatment courts needs to involve educating court administrators, judges, and politicians about the merits of, and stigma around, the use of medication treatment for opioid use.

Finally, while this study did not find a difference in mortality rates between drug treatment court and adjudication as usual, drug courts have shown to have other positive effects, including reduced recidivism which, among other benefits, reduces criminal justice costs. For example, using the same sample of participants in this study, researchers found that those in the drug treatment court condition had fewer arrests, charges and convictions across the 15-year study period, which is consistent with other research.

Nonetheless, caution must be taken when interpreting this, and other studies’ findings, as an indication of the effectiveness of all drug courts, especially given the participants were in the court system in the late 1990’s – over 20 years ago. Drug courts differ also in their composition, services offered, populations served, community resources available, and state and other local laws. All of these factors likely influence the efficacy of drug treatment courts not only on mortality, but other substance use-related outcomes as well. Moreover, even the same drug court will evolve over time. For example, as noted above since this study has been conducted, the very same drug treatment court studied in 1997 and 1998 has implemented many changes, including: expanding access to medication for OUD, mandatory Naloxone training and prescriptions, increased length of program, and expanded aftercare options, among other changes, all of which could have an impact on long-term mortality. Thus, we can only safely conclude that this particular drug court as it was structured between 1997 and 1998 showed no difference in long-term mortality rates between drug treatment court and adjudication as usual participants.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Participants were randomized in 1997 and 1998. Drug courts, including the specific one studied here, have since changed in ways that could have an effect on mortality rates, particularly in a sample of individuals whose primary or secondary substance is heroin. For example, advances in, and increased access to, medication for OUD could have an impact on mortality rates if this study were repeated today.

- Cause of death data were not available for 10 (approximately 20%) of the 49 people who died during the follow up period. The findings that there were no differences in general or substance use-related mortality between the drug treatment court and adjudication as usual conditions must be considered alongside this limitation.

- Primary substance data were available only for 66.2% of the drug treatment group and 31.3% of the comparison adjudication as usual group. The research team points out that missing primary substance data was unrelated to morality risk or other baseline characteristics. It remains possible, however, that opioid primary individuals were more likely to be missing. Given twice as many in the comparison group were missing data, the comparison group may have had more opioid primary individuals, placing this group at greater risk, on average, for overdose (and overdose death) from the outset. Thus, while we would expect opioid primary individuals to be equal across groups given random assignment, whether the groups were in fact equal at baseline on this key characteristic is not known.

BOTTOM LINE

Criminal justice involved individuals with SUD face multiple and varied risk factors for various substance use-related consequences, including premature mortality.

Evaluating the effectiveness of drug courts is essential for finding ways to mitigate poor substance use outcomes in criminal justice involved individuals. Although this study did not demonstrate a difference in mortality rates between drug treatment court and adjudication as usual conditions, drug treatment courts have evolved in many ways in the 20+ years since participants in this particular study were randomized. Specifically, more treatment options (e.g., buprenorphine and naloxone) shown to reduce opioid use-related deaths are now available and could therefore impact mortality rates if this study were conducted using a similar population today. Still, caution must be taken when interpreting the effects of drug treatment courts, as each individual drug court is unique in its composition, services offered, populations served, community resources available, and state and other local laws. Nonetheless, increased availability of, and access to, medication treatment for opioid use disorder in drug courts (the majority of which serve individuals with opioid use disorder) is likely an important part of initiatives to reduce mortality rates among criminal justice involved individuals.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Current or former criminal justice involved individuals with substance use disorder and their families should be aware of the elevated risk for general and substance use-related mortality, particularly during the period of time following release. They may also wish to ask relevant criminal justice personnel about the availability of drug courts, and the services offered as part of drug court participation.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treatment professionals who work with current or former criminal justice involved individuals with SUD should be aware of their elevated risk for substance use-related mortality, particularly during the period of time following release. Educating criminal justice involved patients with opioid use disorder about the benefits of medication treatment and encouraging them to ask relevant personnel about how to access medications may be one way to reduce mortality rates in this high-risk population.

- For scientists: Additional research is needed to assess the effect of drug courts on long-term substance use-related outcomes, including mortality. Given that the structure, scope, and prevalence of drug courts, as well as treatment options and accessibility, vary throughout the United States, researchers can increase the impact of their studies by taking these factors into account when evaluating the relationship between drug courts and substance use-related outcomes. Given this degree of heterogeneity among drug courts, it could be beneficial to study the effectiveness of certain components of drug treatment courts (e.g., availability of and attitudes toward medication treatment, specific components of judicial monitoring, etc.) on substance use-related outcomes rather than comparing individual drug treatment courts as a whole.

- For policy makers: More funding for drug courts and related research could help identify the ways in which drug courts improve, or fail to improve, substance use-related outcomes in order to better serve criminal justice involved individuals with substance use disorder, and ultimately, mitigate their elevated risk for substance use-related death. Given the large proportion of criminal justice involved individuals with opioid use disorder, ensuring that medication for these disorders is available, accessible, and encouraged, is likely to have a positive effect on this vulnerable population. Education about the benefits of medication for opioid use disorder, including the stigma surrounding its use, could help develop more effective laws and guidance for drug courts so that they could better serve individuals with substance use disorder.

CITATIONS

Kearley, B. W., Cosgrove, J. A., Wimberly, A. S., & Gottfredson, D. C. (2019). The impact of drug court participation on mortality: 15-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 105, 12-18. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2019.07.004