One Glass a Day? The Impact of Low Volume Drinking on Mortality Risk

This relationship between low level alcohol use & lower risk of death is often described as “J-shaped” because the morality risk with abstinence is thought to be greater than it is with low volume drinking, but then rises again as one increases alcohol use to medium & higher volumes.

The assumption is that if you don’t drink alcohol at all you are actually worse off than people who drink a little bit.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

There have been dozens of observational studies during the past 15-20 years suggesting that low levels of alcohol consumption may be associated with lower likelihood of early mortality by reducing risks of cardiovascular and coronary heart disease.

Importantly, however, some researchers have identified several problems with this body of studies, calling into question the validity of the relationship between low levels of alcohol consumption and reduced morality risk. One problem with these studies, for example, is that the abstainer groups often include individuals who were former drinkers, who may have quit drinking for any number of health reasons. These individuals are sometimes referred to as “sick quitters”. Including them in the abstainer group reduces the overall health of this group, and makes it more likely that they will be at risk for poor health outcomes.

This can make it look like people who don’t drink at all are more likely to die early than people who drink moderately.

However, at least some of these people are more likely to die early after they stopped drinking because they were unwell. While some studies adjust their results to account for this “sick quitter” bias, there are several other potential issues.

Examples of other biases include:

- employing shorter follow-up periods (so that there is insufficient time for any harmful effects of low volume drinking to manifest)

- excluding individuals with prior health problems (who might be more likely to be harmed by drinking, even at low levels)

- focusing on older individuals who are vulnerable to a host of other health factors that may be statistically correlated with little or no drinking over time

In the current study, Stockwell et al. highlighted these potential biases of the existing studies. They attempted to address this group of biases by conducting a series of meta-analyses (large combined analyses of several studies at once) that systematically investigated several of these biases that might make it appear as if low volume drinking reduces risk of premature death.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This series of meta-analyses used 87 studies with a total of 3,998,626 individuals through 2014 to examine the relationship between alcohol consumption and “all-cause” mortality (i.e., not due to any specific disease or disorder). Of these roughly 4 million individuals, 367,103 died during the period in which they were studied. Studies of individuals with a range of demographic characteristics were included, though studies were excluded if mortality (i.e., death) could not be separated from morbidity (i.e., disease). The primary independent variable (i.e., predictor) was average daily alcohol consumption in grams of ethanol. It is worth noting that what constitutes “a drink” depends on the country in which one lives (e.g., 14 g of pure ethanol per drink in the United States).

If needed, they defined one “drink” according to the country in which the study was conducted. Researchers used available study data to categorize individuals into several groups: lifetime abstainers; former drinkers and current abstainers; occasional drinkers (up to about one drink per week or less); low volume drinking (more than one drink per week but less than 2 drinks or 25 grams of ethanol per day); medium volume drinking (up to four drinks per day or 45 grams of ethanol per day); high volume (up to six drinks or 65 grams of ethanol per day); and higher volume drinking (more than six drinks or 65 grams of ethanol per day).

As done in prior work, researchers performed a meta-analysis to identify the relative risk of low volume drinking on morality across all 87 studies.

The unique analyses in this study were:

- a) to analyze four groups of studies based on the number of type of abstainer biases present (e.g., including former drinkers in the abstainer group along with lifetime abstainers)

- b) to analyze only studies where all potential biases were accounted for (i.e., only lifetime abstainers were included in the reference group, the alcohol measure was high quality, smoking status was controlled, and the average age of the study population was less than 60 years at intake and at least 55 at follow-up).

They conducted these analyses systematically to determine the impact of controlling for these potential biases, and to determine the most accurate estimate possible of drinking on mortality.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

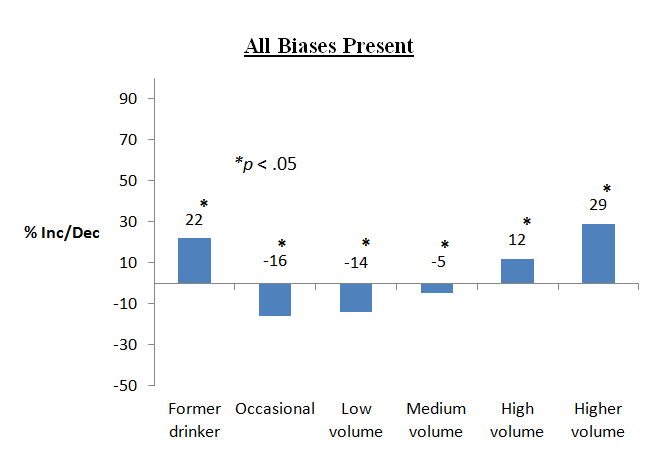

This study replicated the prior finding that, when biases like those detailed above were not controlled, low & medium volume drinkers had reduced risk of mortality compared to abstainers & former drinkers had the greatest mortality risk.

When the reference group was occasional drinkers (one drink or less per week), all individuals except low volume drinkers had an increased mortality risk. In other words, occasional drinkers (one drink or less per week) and low volume drinkers (more than one per week but less than two per day) had similar risks

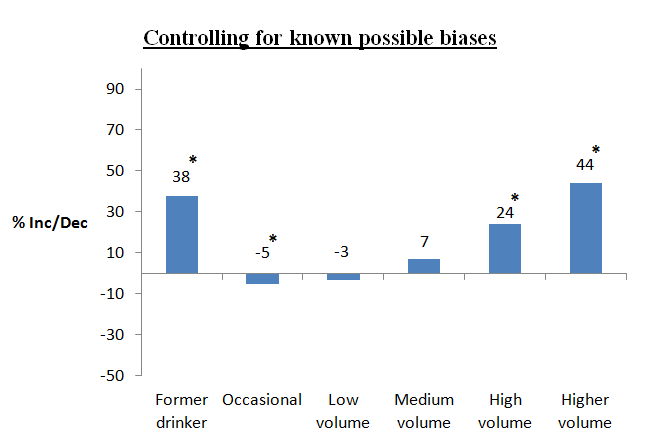

When studies controlled for age at intake, study sex, whether the study was conducted in a primarily White or Non-white country, the quality of the drinking measure used, and former and occasional drinker biases, occasional and low volume drinkers continued to show reduced morality risk compared to abstainers.

However, when analyses also controlled for how long the study was conducted, whether the study included/excluded participants that were ill at baseline, and, within each study, for race/ethnicity and smoking status, the association between occasional as well as low volume drinking and reduced mortality disappeared.

High and higher volume drinking, as well as being a former drinker, continued to pose increased mortality risk.

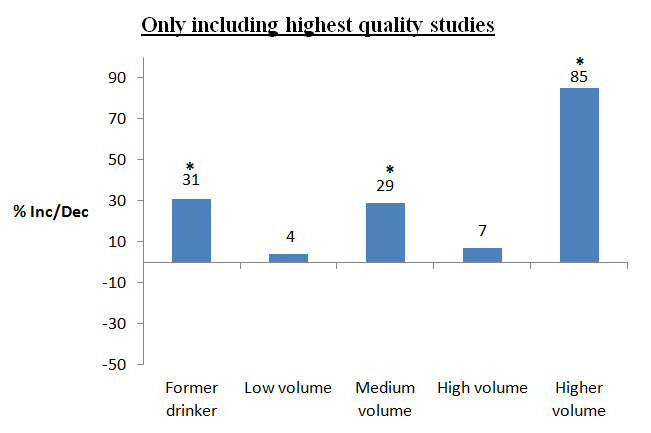

Importantly, when analyses investigated only the 13 studies that were not biased by including former or occasional drinkers in the reference group, a reduced morality risk for individuals who consumed low volume alcohol, on average, was not observed. When only the six highest quality studies were analyzed, the observed risk of drinking was relatively linear.

Of the 87 studies included in the meta-analysis, 65 included former drinker biases, and 50 occasional drinker biases. Though not related to recovery per se, this suggests our understanding of prior research on alcohol and mortality risk may have been hindered by the difficulties of studying the impact of a naturally occurring behavior like alcohol consumption.

As authors of this study noted, even when these limitations are not fully adjusted for, occasional drinkers (one drink or less per week) still appear to have the same health benefit as low volume drinkers. This raises doubt about low volume drinking as a true causal therapeutic agent in the reduction of cardiovascular problems and death. For example, individuals with higher incomes tend to be more likely to drink alcohol – these individuals may have better access to health care and other resources that can help ward off disease and disability (e.g., social support).

In other words, the apparent cardio-protective effect of alcohol would actually be accounted for by any number of health-promoting factors associated with have higher income. The limits of population-level, correlation studies are not a new phenomenon. One real world case, for example, is the body of well-controlled, correlation studies that showed those taking vitamin E had reduced chances of several negative health outcomes compared to individuals who do not take the vitamin. When trials were conducted where individuals were actually randomized to take vitamin E, however, the vitamin did not promote any reductions in the likelihood of developing serious health conditions whatsoever.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

This study is critically important because some doctors have begun to recommend patients consume 1 to 2 drinks per night (particularly wine) to help reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. The merits of this practice are uncertain given myriad health risks of drinking.

Alcohol, for example, is a Group 1 carcinogen according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC; i.e., it is known to cause cancer).

Thus, if a statistical relationship between low volume drinking and reduced morality risk could be attributed to factors other than alcohol consumption itself, the practice would certainly not be ethically sound from a health science perspective. In that case, recommending low level alcohol use would not actually increase longevity and may actually make people ill through increasing the risk of cancer. Another possibility is that the most methodologically rigorous studies will continue to show a relationship between low volume drinking and better health outcomes.

If this is the case, then more funding and efforts should be directed toward identifying the mechanisms (i.e., why this is happening) so that modern medicine can capitalize on this observed benefit (e.g., creating systematic medical recommendations and developing new medications). If drinking is truly related to decreased mortality, it would be important to know: a) the precise dosing range, b) how often people would need to drink and for how long before benefits are experienced, c) to which subgroups of the population these potential benefits might apply; and d) any contraindications against use and potential negative interactions (e.g., with medications).

This study calls into question the idea that low volume drinking (e.g., “1 to 2 glasses of wine per night”) is good for one’s health, particularly for individuals that may have a history of an alcohol problem or alcohol use disorder.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The main limitation of this study is that alcohol consumption was self-reported in the individual studies of the larger meta-analyses, and not validated by a biophysiological measure of consumption (i.e., a “biomarker”). In many cases, this is difficult, if not impossible given the very short half-life of ethanol in the blood stream, but an important limitation to mention nonetheless.

NEXT STEPS

Next steps include using this methodologically rigorous approach to investigate the association between low volume drinking and specific diseases or disease-states.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: The study raises serious doubt about the adage that low volume drinking is good for your health. It is important to encourage your loved one to consider not only the risks of alcohol use on their ability to initiate and sustain recovery, but also the risks of drinking even small amounts of alcohol on their overall health and well-being.

- For scientists: This study represents an important example of how even high quality research published in reputable journals can be susceptible to bias and critical methodological limitations that can lead to misleading and potentially harmful conclusions Given the immense social, health, and economic burden associated with alcohol use, future studies should attempt to build on the approach here in order to accurately model the long-term effects of drinking on health outcomes.

- For policy makers: The study raises serious doubt about the notion that low volume drinking is good for your health. Clear policies that continue to curb overall rates of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking in particular (e.g., limiting alcohol outlet density and raising taxes) should be strongly considered.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The study raises serious doubt about the notion that low volume drinking is good for your health. It is important to discuss with your patients not only the risks of drinking on their ability to initiate and sustain recovery, but also the risks of drinking even at small doses on their overall health and well-being (e.g., increased risk of cancer at low consumption levels).