Can recovering peers help others with opioid use disorder get treatment?

Though there are a number of effective treatments for opioid use disorder, engaging people in treatment remains one of healthcare’s most persistent and vexing challenge. The present study tested a new initiative in Chicago that has individuals in recovery from opioid addiction engage people in active opioid addiction in the community to help link them to treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The US is experiencing an unprecedented public health crisis with the current opioid epidemic. Though effective treatments exist, the vast majority of people struggling with addiction are not connected with treatment. There are numerous reasons for this, but some of the more common reasons include the complexity of navigating healthcare systems—particularly for individuals with little or no insurance—distrust of healthcare providers due to negative past experiences, fear of stigmatization, judgement, or punishment, and difficulty making it to appointments in active substance use.

This study tested a novel way to shepherd people to care through the utilization of peer outreach workers or have the ability to overcome some of these barriers to care by linking individuals to treatments and helping them navigate healthcare systems.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This pilot study investigated the feasibility of an intervention that utilizes peer outreach workers to identify out-of-treatment individuals with opioid use disorder and link them to treatment.

- READ MORE ON STUDY METHODS

-

Participants were recruited from several community ‘hot spots’ in the Chicago area identified by peer outreach workers as having high concentrations of opioid use and high rates of overdose. Target areas included specific neighborhoods, parks, bus stations, shelters, and fast-food restaurants.

Participants were 70 adults with opioid use disorder who were not currently in substance use disorder treatment. Most participants were male (73%) and African American (94%), and 6% were Hispanic. Nearly all were rated with high severity on a substance use disorder screener, and most (61%) had a history of opioid-related overdose, ranging from one to eight times; over half of these people (23/43, 53%) had received naloxone to counter an opioid overdose at least once.

Potential study participants were approached in the field by peer outreach staff who started a conversation by talking about the local heroin problem. They then explained that they were seeking individuals who use heroin, but are not currently in treatment, for a study with the goal of getting people into care. If the person expressed interest in participating, study staff phone-screened the prospective participant for study eligibility.

Once enrolled in the study, participants met with a treatment linkage manager who used motivational interviewing, discussed the benefits of treatment, engaged in problem solving about expressed barriers to treatment, and provided links to treatment. Linkage managers stayed in contact with participants who entered treatment to keep tabs on their status. If a participant dropped out of treatment, they would attempt to reengage them. For participants who didn’t initially want a treatment referral, the linkage manager maintained weekly contact for 30 days so that participants who changed their mind about treatment could be referred.

MEASUREMENT: The authors gauged the success of this novel, peer-outreach intervention by measuring, 1) the number of individuals who showed up to the first recovery management session following an interaction with a peer outreach worker, 2) the number of these individuals that were subsequently admitted to methadone treatment, and 3) of these individuals, how many of were still in methadone treatment at 30- and 60-day follow-up.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

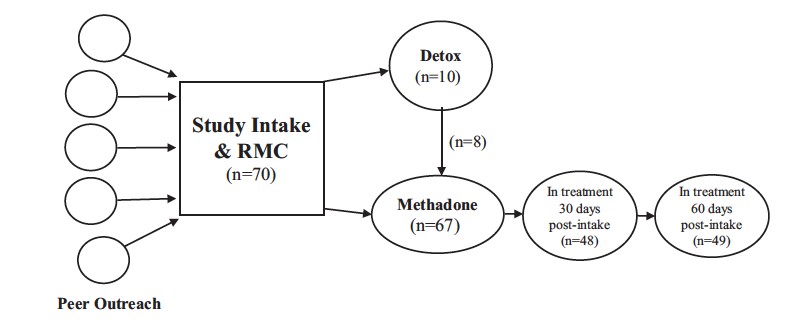

- • Over the course of 8 weeks, peer outreach workers identified 88 people actively using opioids. 72 were screened as eligible, and 70 showed to the treatment linkage meeting.

- Of those showing up to the treatment linkage meeting, nearly all (67/70, 96%) were admitted to methadone treatment, with a median time from initial linkage meeting to treatment admission of 2.6 days.

- The majority of participants were still in treatment at 30 and 60 days post-intake (69% and 70%, respectively).

- Researchers also identified a high-risk sub-group of participants who had previously received naloxone for an opioid overdose, and were younger and typically male. These participants had one third of the odds of being in treatment at 30 days post-intake compared with other participants.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings suggest that a peer outreach coupled with a treatment linkage and engagement intervention is a promising approach for identifying and engaging out-of-treatment opioid users in treatment. Relatedly, hospital emergency departments that link individuals to treatment following presentation for opioid overdose are thought to increase the likelihood individuals seek treatment. Utilizing peer recovery support staff in such medical settings (which often represent a rare point of contact with the healthcare system for individuals with opioid use disorder) may be of particular benefit.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As is typical in pilot studies such as this, there was a small sample size and the research was confined to a single research site. Additionally, the sample was mostly of one race and male. Future studies will need to replicate these findings in larger, more diverse samples, and in diverse settings.

- As noted by the authors, treatment options for participants were limited to methadone pharmacotherapy, which may have discouraged some participants. It is possible that individuals presented with a range of treatment options would be more likely to agree to treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study highlights the important role peers can play in the recovery process. Though not linking people to formal treatment, peer-based recovery support groups (e.g., AA, NA, SMART Recovery) can be a critical bridge to recovery for many because, like peer outreach workers, individuals in these groups have the ability to meet other people seeking recovery ‘where they’re at’. Additionally, many treatment systems now utilize peer recovery coaches who can be a valuable recovery resource. While more research is needed on these recovery supports for individuals with opioid use disorder before they can be recommended based on science, they are unlikely to be harmful and are worth trying.

- For scientists: The present study shows the great potential of peer outreach workers to help link individuals with opioid use disorder to treatment. More research is needed in this area to determine for whom, and under what conditions such interventions are most effective, and how these interventions can be manualized and disseminated.

- For policy makers: Opioid use disorder exacts a prodigious public health toll. Low cost interventions such as the one described in this study have tremendous potential to reduce mortality, engage individuals in treatment, and ultimately save in healthcare and other costs. Moreover, interventions such as this have the ability to engage typically hard to reach populations like individuals experiencing homelessness.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: It has long been appreciated by professional treatment providers that peers are uniquely positioned to meet patients ‘where they’re at’ (literally and figuratively) and build trust and rapport quickly. The present research underscores the valuable role peers might play in the recovery process, and highlights the case for peer outreach and recovery coach utilization in treatment systems.

CITATIONS

Scott, C. K., Grella, C. E., Nicholson, L., & Dennis, M. L. (2018). Opioid recovery initiation: Pilot test of a peer outreach and modified Recovery Management Checkup intervention for out-of-treatment opioid users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 86, 30-35. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2017.12.007