Asking recovering individuals how to measure recovery capital

Resources used to initiate or sustain recovery are often referred to as recovery capital. Measuring such complex concepts with a single survey can be difficult and existing measures have not focused on diversity. This study examined more diverse populations.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Recovery capital is a broad concept that aims to capture all the potential resources an individual could use in their recovery journey (i.e., their process of recovery from a substance use disorder). The recovery capital framework proposes that there are both intangible and tangible resources at several levels of one’s environment: the individual level (one’s own personal resources such as motivation to change; coping skills), the interpersonal level (the social resources one has access to as a result of relationships and interactions with others), and the community level (the resources one has access to as a result of where they live, work, and play).

Measuring such a broad and complex concept with a survey can be difficult and existing recovery capital measures were developed with fairly similar samples. While existing measures are still helpful for understanding recovery, they may be missing key aspects of the recovery journey for different population sub-groups. Indeed, there is a growing body of addiction treatment and recovery research that indicates that many groups of individuals experience very different recovery journeys due to their personal characteristics and experiences, especially minorities. That is, individuals that are part of distinct ethnic or racial, income or education (socioeconomic), gender, and sexual minority status may have or prioritize different recovery resources than what is captured in our current recovery capital measures.

The researchers in this study wanted to engage key recovery stakeholders, from a wide variety of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds, in the survey development process. They involved these recovery stakeholders to see if there were additional sources of recovery capital that they had not considered and if there were better ways to capture recovery capital among these diverse populations. In this study, they report on their process and key findings from the work to develop the novel Multidimensional Inventory of Recovery Capital.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

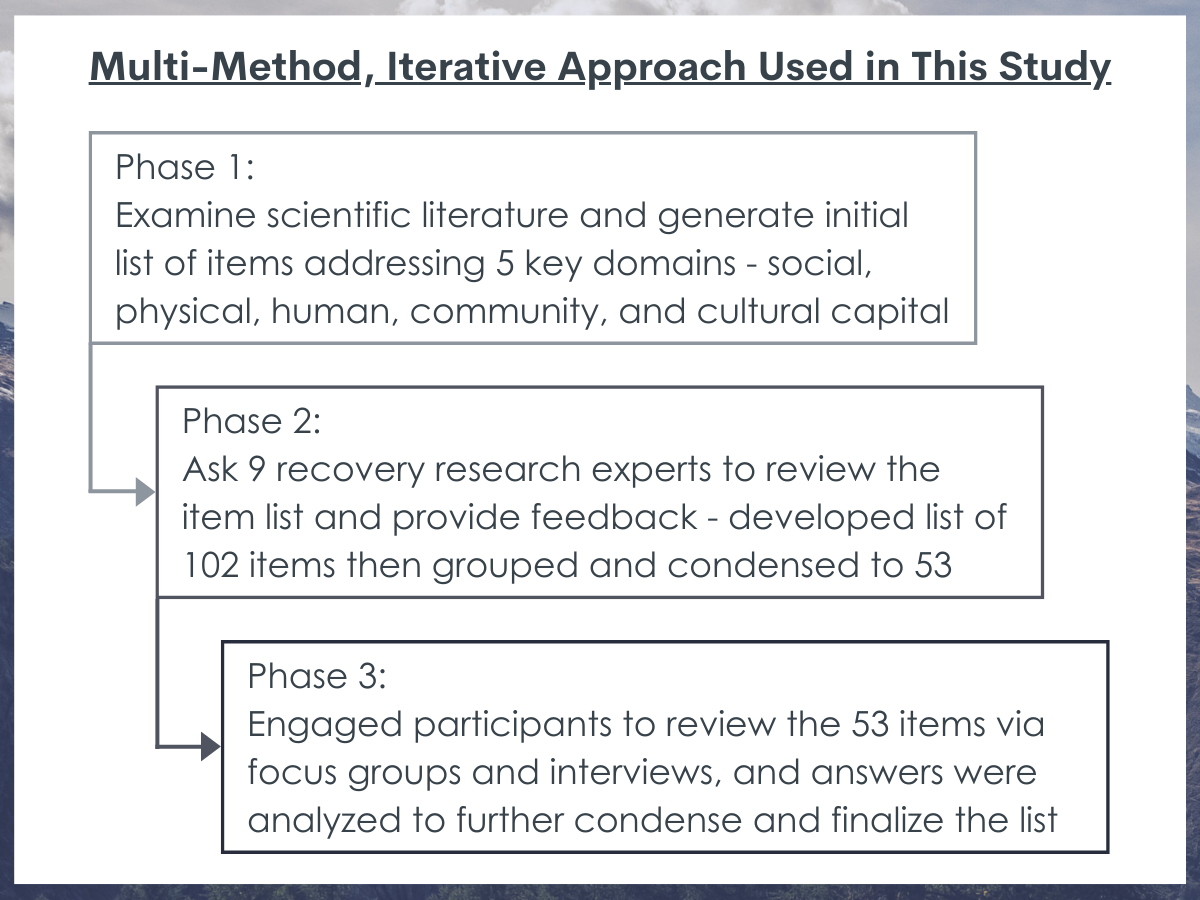

The researchers used a multi-method, iterative approach to this study. First, they examined the scientific literature to organize empirical elements from one of the initial recovery capital frameworks developed by Cloud and Granfield in 2008. They used this framework to generate an initial list of items that addressed each of the 5 domains used: social, physical, human, community, and cultural capital. They also considered both positive and negative elements for the items, so that they would capture both resources and barriers to building recovery capital.

In the second phase, they asked 9 recovery research experts to review the item list and provide feedback. After this phase, they developed a list of 102 items which they grouped and condensed to a list of 53 items to present in the third phase.

In the third phase, they engaged participants in reviewing a list of 53 items for the tool through a series of focus groups and interviews. In these structured focus groups and interviews, a researcher facilitated the activity by reading each item aloud and asking participants to share their feedback. The researchers also asked participants to complete a brief set of surveys so they might better understand their responses based on several key individual characteristics. These surveys included: demographics, treatment history, prior problem severity, and current alcohol and drug use. The research team analyzed the interview and focus group data using a type of applied qualitative analysis, the framework approach, with the aim of finalizing a list of items for their scale.

The two groups of participants engaged in the qualitative (third) phase of the study were: (1) Service providers in any aspect of the substance use disorder treatment and recovery field; and (2) People in recovery from alcohol use who had resolved a problem with alcohol for at least 30 days. To ensure they had a diverse group of recovering participants, the researchers used a special form of sampling, called quota sampling, to get individuals with diverse incomes, races, and ethnic identities.

The resulting sample that researchers sought feedback on the recovery capital tool from included 9 service providers and 23 individuals in recovery from alcohol use. The sample was primarily cisgender female (58%) and around one quarter of respondents (26%) identified their sexual orientation as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or ‘other.’ People of color comprised just under half of the recovery sample (43%) and of the total sample (39%). Low-income individuals were nearly half (47.8%) of the recovery sample and 35.5% of the total sample. Most of the recovery sample (61%) identified as having resolved their alcohol problems for two years or more, while 13% had resolved their problems for between 1 and 2 years. There was also diversity between participants‘ recovery pathways. For example, in the recovery subsample, 35% of participants had attended inpatient treatment for alcohol problems and 52% had attended outpatient treatment. Additionally, just under half (48%) attended self-help groups in the past 30 days, and 30% had never attended self-help groups. Around one fifth of recovering participants (22%) had attended both inpatient and outpatient treatment in addition to self-help groups, but 17% had no experience with inpatient or outpatient treatment or self-help groups. Finally, just under half of recovering participants reported occasionally using alcohol or other drugs (44%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Stakeholder perspectives resulted in many changes to initial survey items.

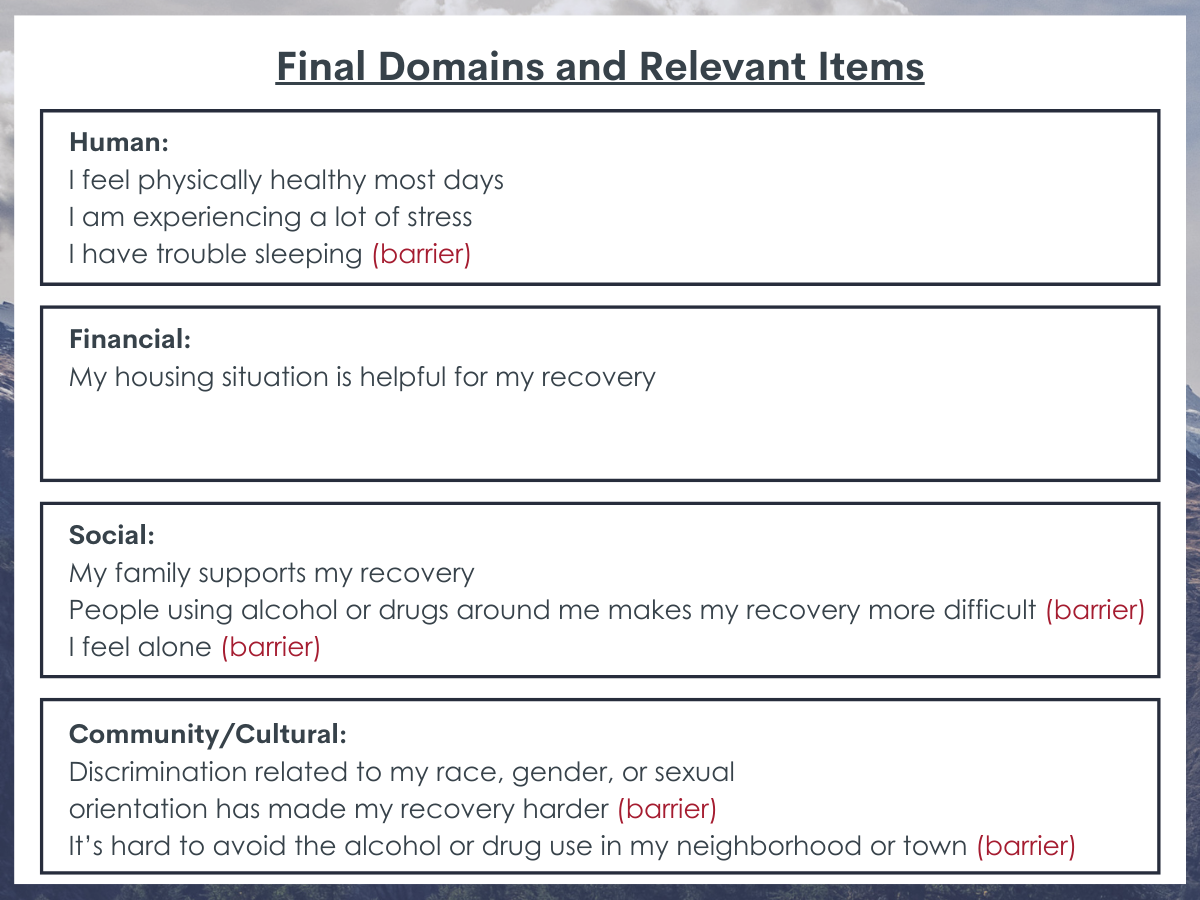

The Multidimensional Inventory of Recovery Capital developed by the researchers in this study through the multi-step process was 49 items.

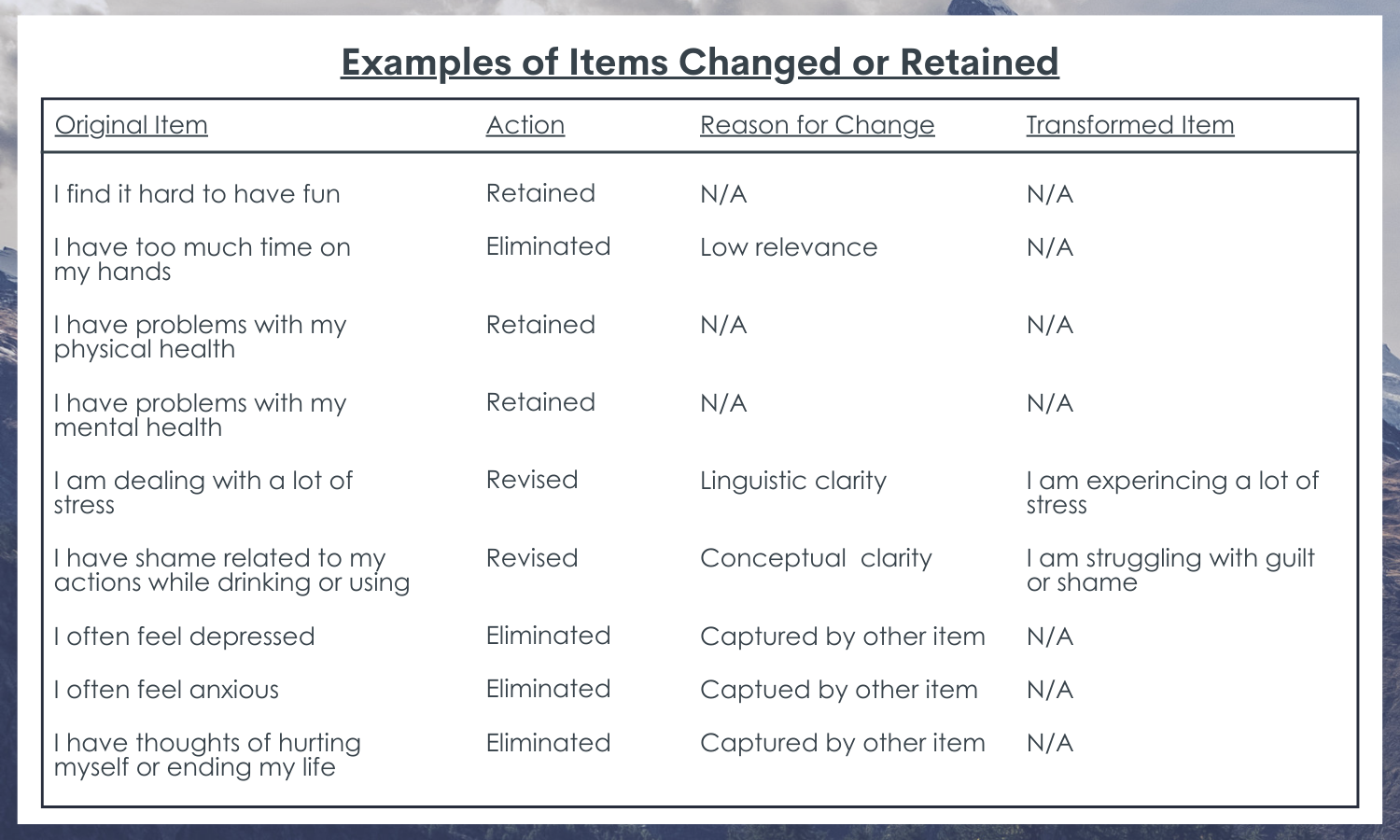

As a result of their testing process, 10% of the items the researchers initially proposed were kept without any changes. Some of the unchanged items that were widely agreed on by participants were measures of physical health and the importance of being part of a recovery community. Some items were also kept but reworded. For example, some items were reworded to reflect more of an active role of those in recovery versus passive roles (e.g., to remove suggestions of one being “helped by” others). Participants also felt that questions that placed a value judgement, for either their own or other’s behavior, could be reworded. For example, they suggested changing how others’ substance use was asked about in the survey to remove statements about others’ “problem” substance use.

Recovery stakeholder characteristics were related to only few, albeit key, changes to survey items.

Overall, the researchers found that there were not large differences in how participants responded to the proposed survey items by their income or racial/ethnic identity. They did, however, find some different responses by recovery pathway of respondents. For example, the researchers found that an item on spirituality, “I have a spiritual practice that helps me in recovery”, was interpreted differently by those who had positive engagement with 12-step meetings (spiritual focus for recovery) and those who did not.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study used a systematic, qualitative approach to elicit and synthesize responses to proposed recovery capital scale items from 9 practitioners and 23 individuals in recovery. The work highlights the importance of thoughtful stakeholder involvement when creating a scale to understand recovery processes. That is, although the initial aspects of scale development involved pulling together items from the scientific literature and recovery research expert review, the researchers in this study found that their approach identified key wording changes that might help participants engage more with completing a survey and may help them respond more accurately to questions about their recovery capital. As well, this work is a reminder that capturing the diversity of participants’ racial/ethnic background, treatment history, and lived experience in measures of recovery capital should be sensitive to the idea that important recovery resources for some, may not be prioritized as highly for others.

Overall, the findings indicate that more nuanced work that prioritizes stakeholder involvement in all aspects of the research process, is needed to understand the recovery process and recovery capital among diverse populations.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Results reflect a single small group of stakeholder participants and results may vary across other samples of similar groups as opinions are likely to vary.

- The sample of those in recovery were only those who had recovered from alcohol use disorder alone or in combination with other drugs. This may limit the use of this new recovery capital scale among individuals who are in recovery journeys from other substances. Specifically, there are a variety of differences between those recovering from alcohol, a legal substance, and other illicit substances in terms of the nature of the consequences, stigma, and structural barriers, to name a few.

BOTTOM LINE

This study of responses to proposed recovery capital scale items from key recovery stakeholders reveals how important it is to engage individuals with experience in the issue at hand, in the process of creating new measurement tools. This type of research is necessary so that scientists can ensure that measures capture what they are meant to capture and in a way that will reduce participant confusion or bias.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The concept of recovery capital can be an important one to use to frame a recovery journey in that it asks the question: What are one’s resources and barriers for recovery? Asking your loved one about what they see as their strengths and barriers for their recovery, may help family members and friends show support for each other and identify areas to more actively assist in another’s recovery journey. It is important to remember, however, that any different levels of recovery capital, or gaps in recovery capital, do not reflect shortcomings of the individual. These are simply areas where one may need scaffolding through additional community or social supports. Knowing where there are resources and barriers is the first step in the recovery process and individuals may see other factors as resources than the ones that the traditional recovery capital model identifies.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: A recovery capital measure, like the one discussed in here, can be helpful to understanding where a client has resources and barriers for their recovery. Areas of resources can be used to build upon their success in their recovery journey, while areas of barriers can indicate where a client may need additional supports or linkages to care within the larger system of care or the community. Assessing recovery capital and providing those key linkages may be the first step to providing a client with a supported recovery pathway outside the clinical setting, through a model of measurement, planning, and engagement. Additionally, it will be important to discuss with clients where they might have unique sources of recovery capital (or barriers to building it) that are not captured on standardized recovery capital measures, as these will also be areas that can used (or addressed) in their recovery journey.

- For scientists: The kind of work presented by the authors of this study is vital to moving the addiction recovery field forward. Presenting not only the modified scale, but how the researchers went about making those modifications and highlighting how they involved stakeholders can support other research teams in providing a roadmap for doing this type of work in their own research endeavors. There are also several ways that this research could be advanced, including by replicating the process used here to examine whether individuals with different recovery pathways (e.g., from substances other than alcohol) perceive a need for different types of recovery capital items. One other way to advance this work, as suggested by one of this study’s participants, is to continue the use of qualitative research and consider how more open-ended items could be incorporated into the assessment of recovery capital. Finally, examining how well this scale can explain or predict recovery outcomes, as well as its sensitivity to change over time, among different recovering populations will be an important next step.

- For policy makers: The research approach presented in this study, that of systematically involving key recovery stakeholders in measurement development, is important to moving the addiction research and practice field forward. Funding to support this work – that is, to support the research team as well as provide compensation for stakeholder participants offering their time and expertise – will help to continue the infrastructure needed to develop and validate evidence-base measurement tools.

CITATIONS

Bowen, E., Irish, A., LaBarre, C., Capozziello, N., Nochajski, T., & Granfield, R. (2022). Qualitative insights in item development for a comprehensive and inclusive measure of recovery capital. Addiction Research & Theory, 1-11. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2022.2055002