Does recovery capital influence treatment benefit?

A recent randomized controlled trial showed that a motivational interviewing-based case management treatment resulted in better 12-month criminal justice outcomes among individuals in recovery residences, who were on probation or parole, but only for those who attended at least one treatment session. Qualitative data suggests that the level of ‘recovery assets’ (commonly referred to as “recovery capital”) participants have may have played a role in the effectiveness of the treatment. This secondary data analysis study examined that question.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Recovery residences can provide a safe, substance-free living environment to individuals currently on parole or probation who struggle with problematic substance use. Given the many challenges recovery residents face (e.g., meeting the expectations of the parole or probation agreement, adapting to the recovery residence environment, accessing needed services, developing plans for employment or job training, and enacting those plans), researchers developed an intervention that would provide case management support while also prompting participants to anticipate and respond to these various challenges. The goal of this intervention, which deployed case management services using a motivational interviewing style, was to help improve residents’ outcomes, which they defined broadly in terms of substance use outcomes, HIV risk, legal problems, and various secondary outcomes such as living arrangement, experience of psychiatric symptoms, and employment. To test the effectiveness of the new intervention, researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial, which showed better criminal justice outcomes one year after recovery residence entry in participants who received one or more motivational interviewing case management sessions vs. those receiving usual recovery residence services (e.g., referrals to services in the community).

While both groups showed improvement on other outcomes including substance use, the criminal justice outcome was better in the treatment group, but only when analyses were restricted to those completing at least one treatment session. When reviewing the audiotapes of the sessions completed for this randomized controlled trial, the investigators noted that substantial differences existed between participants in terms of their ‘recovery assets’, a concept grounded in the more widely known construct of recovery capital. Recovery capital has been defined by Granfield and Cloud as the internal and external resources that individuals can draw upon to initiate and maintain a recovery effort. Importantly, this definition also incorporates the existence of negative recovery capital factors that can impede progress, such as poor health and incarceration. Given the complexity of the challenges faced by criminal justice-involved individuals living in recovery residences, the researchers conducted analyses to explore the impact of recovery capital on the success of the intervention.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study is a secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled trial that involved 330 individuals living in recovery residences, all of whom were probationers and parolees. In the original study, participants were randomized, per house, to either receive motivational interviewing case management (149 residents from 22 houses) or usual recovery residence services (181 from 27 houses). The treatment was delivered by therapists with experience in motivational interviewing and case management who aimed to meet with participants three times during their initial month of residency at the recovery residence, and once monthly thereafter. Only the first meeting was required to be in person; subsequent check-ins could occur by phone. Treatment delivery proved difficult, with 30% of the participants assigned to the MI case management condition not receiving any treatment.

The outcomes of interest were six subscales of the Addiction Severity Index Lite. This is a clinician-rated scale that covers several domains, of which the investigators focused on experiences during the past 30 days for the following six domains: alcohol use (e.g., any, to intoxication, money spent, experiencing alcohol-related problems); drug use; employment (e.g., dollar amount earned, dollar amount received in support); legal status (e.g., currently on parole/probation, number of days engaged in illegal activities); medical (e.g., number of days experienced medical problems); and psychiatric status (e.g., experienced depression, anxiety, hallucinations, difficulty concentrating, suicidality). Outcome data were able to be collected on 81% of the participants 12 months after they started living at the recovery residence.

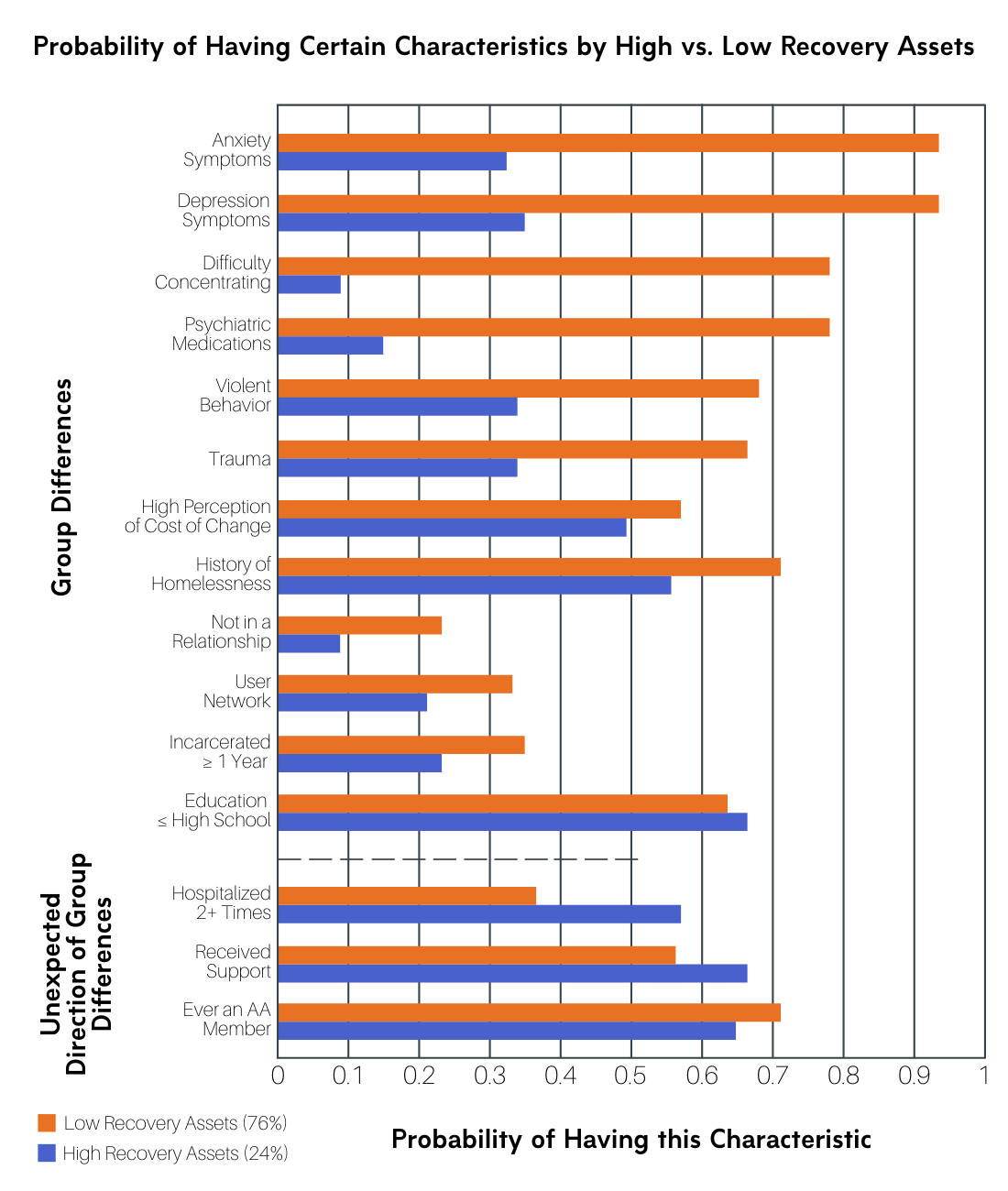

In this secondary data analysis, participants were further divided into residents with high (79 residents, 24%) vs. low (251 residents, 76%) recovery capital. To do so, the researchers used an exploratory data analysis technique called “latent class analysis”, which divided study participants into groups based on 25 indicators of recovery capital, as assessed at baseline. These indicators included broad factors (i.e., demographics), targeted outcomes (e.g., alcohol and drug use, social network support, criminal justice involvement), and related constructs (e.g., past trauma, psychological and physical health, motivation for change).

Next, the authors tested if this grouping (high vs. low in recovery capital) influenced treatment effects. A complicating factor was that treatment delivery was not successful in many cases. To capture the effect of not receiving treatment, the authors conducted the same set of analyses three times, each time using a different cut of the treatment group: using all participants randomized to the treatment group; including only those who completed at least one session (75%); and including only those completing at least three sessions (55%).

Study participants were predominantly male (74%), on average 39+/-12 years of age, most frequently White (47%), African American (24%) or Hispanic (19%), and frequently had no more than a high school education or less (64%). Just over one-third (38%) of participants were mandated to live in a recovery residence as a condition of their parole/probation. Most study participants met diagnostic criteria for DSM-IV ‘drug dependence’ (81%), some for ‘alcohol dependence’ (36%). The most commonly used substances were methamphetamines (41%) and alcohol (35%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

First, there was a clear differentiation between those high in ‘recovery assets’ (24%) vs. low (76%). The most defining features of this difference pertained to psychiatric symptoms, lifetime trauma, and hospitalizations. Contrary to the researchers’ expectations, and contrary to the ‘high recovery capital’ label, participants in the ‘high recovery capital’ group were more likely to have been hospitalized two or more times, more likely to have received rather than given support, and less likely to have been an AA member.

Figure 1.

For those with low recovery capital, participants who received the motivational interviewing-based case management did not do any better than those receiving services-as-usual on any of the outcomes.

For those with higher recovery capital, on the other hand, participants who received the motivational interviewing-based case management generally did better than those receiving services-as-usual. For those assigned to the motivational interviewing case management group, whether or not they actually attended a treatment session, they had better mental health at the 12-month follow-up compared to those assigned to services-as-usual. For those assigned to the motivational interviewing case management group and attending at least one session, they had better mental health and legal outcomes. Finally, for those assigned to the motivational interviewing group and receiving at least three sessions, they had better mental health, legal, and drug (but not alcohol) use outcomes.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Perhaps most vividly, this secondary data analysis highlights that the vast majority of recovery residence residents who were ex-offenders on probation or parole had very low levels of recovery assets (76%). Moreover, these low levels of recovery assets were largely defined by the presence of impeding factors, such as the experience of psychiatric symptoms and a history of trauma, where particularly the presence of depression and anxiety symptoms is noteworthy. These occurred in >93% of the low recovery asset participants. This finding suggests that the clinical profile of the majority of those living in the recovery residences on parole/probation is complex and they are likely to face many psychosocial challenges.

Most importantly, this secondary data analysis highlights the potential importance of recovery capital in how individuals might respond to treatment and recovery services. Recovery capital played a pivotal role in recovery residence residents’ ability to benefit from the treatment under investigation – motivational interviewing case management. This treatment was found to be insufficient to help those in recovery residences with low recovery resources. Given that the lack of such resources was the norm rather than the exception in this group, this finding implies that this particular intervention is insufficient for the majority of its intended target group and those who are most in need. As such, these findings add to the growing bulk of evidence that indicates that among those living in recovery residences with high psychiatric severity, a disproportionally high number struggle with achieving abstinence and are less likely to benefit from social support.

While previous research has highlighted the importance of addressing the perceived challenges of abstinence, especially for high psychiatric severity residents, the examined motivational interviewing case management treatment did not appear to be able to impact the target population sufficiently. More efforts are needed to help individuals in recovery who have little available recovery capital. Perhaps linkage to recovery community centers, or connections with recovery coaches, who are increasingly used in emergency room and primary care settings, may be able to further support them.

For those high in recovery resources, the treatment appeared to be beneficial, at least for those who were ready and willing to participate in it. Importantly, “high in recovery resources” is a very relative term, as even those in this ‘high’ resources group struggled with homelessness (55%) and had a history of trauma (33%).

- LIMITATIONS

-

- While the classification into groups with high vs. low recovery capital is thought-provoking, comparing these groups analytically thereafter, and interpreting the results, is made difficult by the fact that some variables acted in a counter-intuitive fashion. For example, having been an AA member was more common in the low recovery capital group, even though AA represents social network support. These complexities make it difficult to understand the group differences.

- While the sample size restrictions for the treatment group make sense, it should be noted that the grand equalizer of randomization is no longer in effect for those sub-sample comparisons. That is, clinical trials use randomization to ensure that the only systematic difference between two groups of people is the treatment they received. Thus, any differences found between groups after the treatment can then be attributed to the treatment, not other factors that might also be related to the observed outcome. In the case of this study, it is possible, if not likely, that the control group continued to contain participants who were unwilling/unable to participate in treatment. Thus, in comparing the subset of the treatment group who completed at least 3 treatment sessions to the control group, willing and able participants in the treatment group were compared to a mix of control participants, some of whom may have been willing and able, while others may not have been.

- The comparison that showed the most treatment differences, that is treatment participants with 3+ sessions vs. control, tested within the high recovery capital group, is an effect that describes a very small subset of the overall sample (i.e., n≈16; the 24% sub-sample of the n=65 treatment group participants who were retained for the 12-month assessment). It is not clear whether this group of participants with high recovery capital and the highest levels of treatment engagement meaningfully generalizes to the population of individuals with criminal justice histories living in recovery residences.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Building recovery capital is an important means to support the initiation and maintenance of recovery efforts. The lack of such recovery capital can render even intensive, very specifically tailored support insufficient, underscoring the importance of building recovery capital from multiple angles.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Motivational interviewing case management may be beneficial to recovery residence residents on parole/probation who do not struggle with psychiatric comorbidities. The treatment manual is freely available upon request from one of the developers of this treatment, Dr. Jane Witbrodt. Linkages to community services that can assist with medical, mental health, legal, and employment issues would provide important additional support. Recovery community centers may be great venues to provide support on multiple of these dimensions.

- For scientists: There continues to be an unmet clinical need for supporting individuals with substance use disorder who are on parole/probation and have psychiatric comorbidities. Novel approaches to support them need to be developed, and existing and emerging practices that explicitly support the building of recovery capital need to be further researched so as to determine their effectiveness. Important examples of existing approaches in need of further study are recovery coaches and recovery community centers, as highlighted by a recent Request-for-Applications by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has already been supporting research on such recovery systems of care for some years.

- For policy makers: Even recovery residences require some financial resources. For those in recovery residences on parole/probation, it is particularly challenging to find a job given their criminal justice history. Rewarding workplaces for taking on individuals on probation/parole could make an important difference in enabling them to earn enough to afford a beneficial living environment, such as a recovery residence. Additionally, a higher level of care appears to be increasingly indicated for individuals on probation or parole who struggle with substance use who have significant psychiatric difficulties.

CITATIONS

Witbrodt, J., Polcin, D., Korcha, R., & Li, L. (2019). Beneficial effects of motivational interviewing case management: A latent class analysis of recovery capital among sober living residents with criminal justice involvement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 124-132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.017