One “bad apple” spoils the bunch? Opioid treatment race inequities across the US driven by those in New York City

The opioid overdose crisis has focused primarily on White individuals, though overdoses are increasing more in Black than White individuals. This national study of metropolitan areas found racial disparities in treatment completion, but the Big Apple was at the heart of it all.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Unlike former drug crises in the US, the current opioid overdose crisis has been characterized by its effects primarily on White families as portrayed in media headlines like the “In Heroin Crisis, White Families Seek Gentler War on Drugs.” Although 90% of those who tried heroin for the first time in the last decade were White, the largest increase in opioid-involved deaths were among individuals who identify as Black (25.2% more Black people had an opioid-involved death in 2017 compared to 2016). In fact, lethal drug poisonings – including but not limited to opioid-involved overdose – among individuals who identify as Black in urban US counties rose by 41% in 2016 compared to only 19% among Whites. These patterns point to questions regarding racial and ethnic differences in treatment completion rates in large metropolitan areas given that treatment completion is associated with a better prognosis. This study sought to determine if there are racial and ethnic disparities in first time treatment episode completion for patients reporting opioids as their primary substance in large metropolitan areas in the US. They probed further into which US cities, specifically, are accounting for these nationwide racial and ethnic disparities.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used data from the 2013 TEDS-D (Treatment Episode Dataset – Discharges) which is a national survey of mostly publicly–funded treatment programs. The sample was limited to adults whose primary substance was opioids living in a metropolitan statistical area (i.e., a geographic location with a high population density) with a population greater than one million. Residential and outpatient treatment settings were included. The variable of interest was race and ethnicity with categories that included non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian (including Pacific Islanders), and Other race or ethnicity. This variable was examined in relation to treatment completion, defined as “all parts of the treatment plan or program were completed,” and where non-completion included the designations of “left against professional advice” and “terminated by the facility” (SAMHSA, 2015). The statistical models tested were adjusted for gender, age, education, employment, living arrangement, treatment setting, medication for opioid use disorder, referral source, primary route of opioid administration, and the number of substances used at treatment admission. Adjusting for such variables in the tested models helps to determine the relationship between race and ethnicity and treatment completion independent of these other factors. The final sample consisted of 34,380 admissions located in 42 metropolitan areas.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

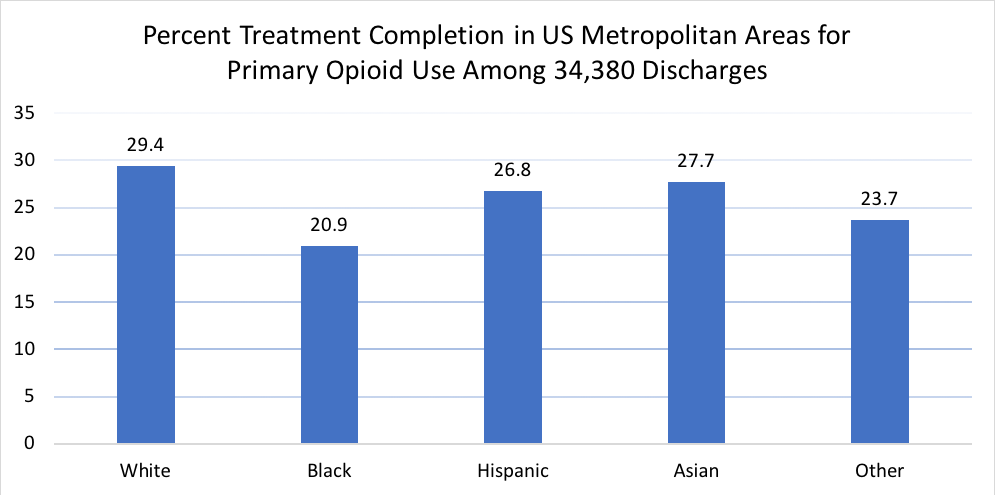

Treatment completion for primary opioid use varied significantly by race and ethnicity with White patients having the highest completion rate (29%) and black patients having the lowest (21%). Hispanic individuals were closer to Whites (27%) in terms of first episode treatment completion (see Figure below). Disparities persisted after controlling for confounding variables where Black patients were 82% as likely to complete treatment compared to White individuals and Hispanic patients were 81% as likely.

Source: Stahler & Mennis, 2018

A closer look revealed that only 3 of 42 metropolitan areas examined in the study showed significant racial and ethnic disparities in treatment completion for primary opioid use. In New York City (which accounted for 23% of all discharges in the sample), and the smaller cities of Buffalo, NY and Riverside, CA, patients with a Black race were significantly less likely to complete treatment than patients with a White race. Similarly, patients of Hispanic ethnicity were less likely to complete treatment than White patients in Riverside and New York City.

In New York City – from which 23% of the total sample derived – treatment completion rates among White patients who use heroin versus other opioids were about the same (41% heroin and 40% other opioids), but were significantly lower among Black patients (26% heroin and 43% other opioids) and Hispanic patients (24% heroin and 33% other opioids). A similar pattern was observed in the entire dataset.

Treatment completion rates varied widely across metropolitan cities, ranging from 9% in Baltimore to 52% in Hartford. Completion percentages for patients who identified as Black varied from 0% in Kansas City to 60% in Denver, with a similar range for Hispanic patients varying from 4% in Baltimore to 79% in Nashville.

Other factors associated with lower odds of treatment completion overall for primary opioid use included homelessness and using more than one substance. Factors associated with greater odds of treatment completion were being over the age of 50, 12 or more years of education, full-time employment, having attended residential treatment, being referred by the criminal justice system, having other drug or alcohol treatment providers, and having been referred to treatment by one’s employer.

Of the 34,380 total discharges in the sample, only 27.8% completed their first episode of treatment for primary opioid use.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment completion vary geographically and are unevenly distributed across the US. Location disparities may reflect differences in local policies and programs, historical practices towards racial and ethnic groups, cultures of substance use, substance availability, insurance coverage policies, and characteristics of treatment programs that may be specific to certain metropolitan areas. A number of approaches have been proposed to address racial disparities in treatment outcomes such as expanding services to address housing instability (i.e., recovery residences); improving staff acculturation competency, reducing wait times, expanding drug courts given the over representation of African Americans in the criminal justice system, improving trauma-informed care and addressing co-occurring mental health problems.

Leaving treatment early may increase the risk for lethal drug poisoning, therefore, collaborations between treatment programs and harm reduction programs based on a continuing care model may create life-saving opportunities and downstream treatment re-engagement.

Only 27% of discharges (which did not include people using medication long term since they were not discharged) used the current standard of opioid use disorder (referred to in the study as medication assisted treatment, or MAT, which generally refers to buprenorphine or methadone) which shows there should be a greater availability for access to medications in treatment settings.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Severity of opioid use disorder, co-occurring mental health problems and health insurance are related to treatment outcomes but were not available for analysis in the study.

- Patients who used long term medications for opioid use disorder were not included in the analysis because they were not discharged from a program (i.e., their treatment participation was ongoing). It is possible that more Black patients used long term medication thus inflating the disparity in discharge rates.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This national study of treatment completion in metropolitan areas found that racial and ethnic disparities for primary opioid use were mainly driven by New York City (which accounted for 23% of all discharges) and two smaller cities. Premature termination from treatment for opioid use disorder can increase the risk of relapse, ongoing opioid use and harms related to overdose, including death. Inquiring about the treatment completion rate for programs before entering may be an indicator of program quality.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study only highlights the racial and ethnic disparities in treatment completion for primary opioid use disorder in metropolitan cities (New York City was a driver). If you see room for quality improvement when it comes to the outcomes of minority patients, consider incorporating recovery residences into your treatment model (or partnering with local organizations that can help), improving staff cultural competency knowledge and training, and reducing wait times. Also, from a case-management approach it may be helpful to work with local law enforcement and criminal justice officials to prioritize drug courts over incarceration given the over–representation of African Americans in the criminal justice system, improve trauma-informed care and addressing co-occurring mental health problems, and partner with local harm reduction organizations. Although not all of these approaches are empirically tested as a quality improvement approaches to reduce disparities, experts hypothesize they may yield improved equality in treatment and public health outcomes.

- For scientists: This study of US metropolitan cities found racial minority patients were less likely to complete treatment for primary opioid use. There are several promising areas of research that may increase minority retention engagement and improve their outcomes. These include engaging with providers who can prescribe the opioid agonist medication, buprenorphine and its more common formulation buprenorphine/naloxone, local harm reduction services, as well as residential vs. outpatient treatment as Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to receive residential treatment. Addressing health disparities for Black individuals with opioid use disorder remains a critical scientific priority.

- For policy makers: This national study of metropolitan publicly funded treatment centers found that only 27.8% of discharges completed their first episode of treatment for primary opioid use. Further, only 27% were using medications for opioid use disorder like buprenorphine/naloxone, the standard of care to reduce opioid use and opioid overdose risk. Given the increased risk of fatal drug poisoning after leaving treatment, policies that support dissemination and implementation of medications for opioid use disorder and collaborations between treatment programs, linkage of individuals to harm reduction programs, and linkage to recovery residences based on a continuing care model are likely to save lives and help individuals build resources that can help sustain positive health behavior change (i.e., recovery capital).

CITATIONS

Stahler, G. J. & Mennis, J. (2018). Treatment outcome disparities for opioid users: Are there racial and ethnic differences in treatment completion across large US metropolitan areas? Drug and Alcohol Dependence,190, 170-178.