One game at a time: Can brain games help rehabilitate cognitive function during addiction treatment?

Substance use disorder is often accompanied by cognitive dysfunction, which can hinder treatment efforts. This study evaluates the potential for strategy training and brain gaming to improve cognition and everyday life functions in a sample of substance use disorder patients in residential treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Executive function (e.g., decision making, planning) problems are common in substance use disorder patients and this dysfunction increases risk of treatment drop-out. In addition, residential treatment-seekers often present with a history of head injury and psychiatric comorbidity, which can also negatively affect executive function and treatment outcome. Previous studies have attempted to test neuropsychological interventions for improving cognitive function with “drill and practice” or “strategy based” approaches (i.e. teaching effective cognitive strategies). Whereas “drill and practice” primarily targets improvement in cognitive test scores, “strategy based” approaches target functional outcomes (e.g., daily life functioning). Combining these approaches might be particularly effective, but it has yet to be studied in substance use disorder patients. To help fill this gap, this preliminary study investigated whether cognitive retraining (i.e. remediation), integrating both approaches, could improve executive functions, self-regulation, and quality of life among a representative sample of substance use disorder patients.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a controlled sequential groups trial of cognitive retraining in 33 women attending residential treatment for substance use disorder (substance abuse or dependence per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, 4th edition)). The women’s residential treatment facility was located in Sydney, Australia. All participants received treatment as usual (TAU), using the Therapeutic Community model of treatment. Participants were assigned to receive either cognitive remediation in addition to TAU (experimental group; n=16), or TAU with no additional intervention (control group; n=17). Participants were enrolled using a sequential groups design, in which the experimental group was recruited before the control group, helping to ensure that residential treatment participants in one group don’t share their study experience with participants in another group. Cognitive remediation occurred in 12 two-hour group sessions, held over the course of 4 weeks (3 sessions per week). The first hour of each session concerned education and training, with a strong emphasis on executive functions and self-regulation. Instructional modules used traditional instruction, education, exercises and roleplaying, modeled after various cognitive remediation interventions for improving cognition and mental strategies. The second hour consisted of group cognitive retraining on ipads, using a common ‘brain games’ application called Lumosity. Participants were instructed to use and practice strategies learned in hour-1 of the group sessions to complete investigator-defined Lumosity exercises during hour-2 of the sessions. All participants received a set amount of time to complete as many trials as possible. Participants were encouraged to share and discuss strategies useful for completing the exercises, which were sometimes integrated into the learning material. Various domains of executive function were assessed with neuropsychological tasks (performance-based measures sensitive to brain impairment) and self-report inventories (measures that can more closely capture problems with everyday function) at baseline (1 week before intervention) and follow-up (1 week after intervention), with similar assessment intervals for the control (29 days) and experimental (34 days) groups. Cognitive tests assessed working memory, response inhibition (the ability to suppress distracting information in order to attend to the information specifically related to the task), and set-shifting (ability to adjust tactics for handling new information and behaving purposefully to achieve a goal). The outcome measures assessed self-reported problems with executive functions, trait and behavioral aspects of self-regulation, (e.g., impulsivity, self-control, emotional control), craving for alcohol and other drugs, and quality of life.

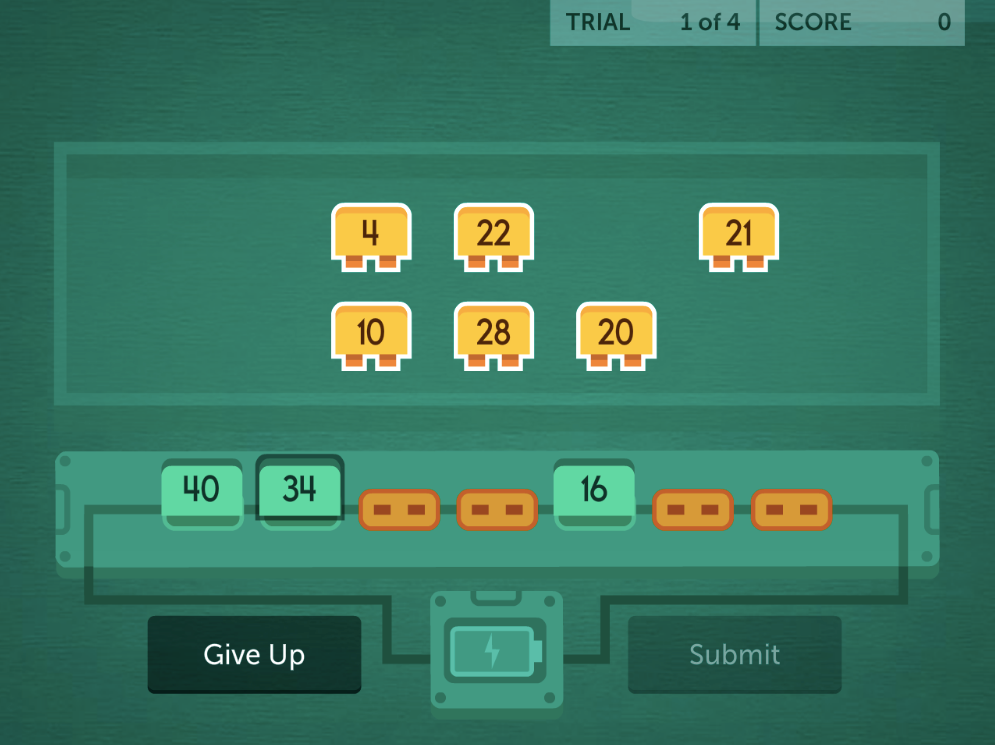

The image above depicts an example of one of the brain games offered by Lumosity, in which players have to solve a number sequence (acquired from Lumosity’s Facebook page).

All participants were abstinent for 7 or more days upon study enrollment and remained abstinent during study participation. To maintain a representative treatment population, individuals were not excluded for a history of head injury (55%) or psychiatric comorbidity (67% current Axis-I based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edition, or DSM-IV). Experimental and control groups were similar in terms of age, education, pre-morbid intelligence, employment, marital status, psychiatric comorbidities, prior episodes of unconsciousness/concussion, and hospitalization after head injury. Primary substance of misuse did not significantly differ between groups. However, a large proportion of the experimental group reported methamphetamine (50%) as their primary substance, whereas the control group primarily reported alcohol (35%) followed by methamphetamine (29%). A history of regular polysubstance use was common across groups (82% of all participants). Treatment duration at baseline was significantly longer for the experimental group (median = 67 days) than the control group (median = 25 days).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Performance-Based Outcomes: The intervention had a positive effect on inhibition.

Relative to the control group, the intervention group showed greater improvement on a neuropsychological test of response inhibition, controlling for baseline performance.

Self-Reported Outcomes: The intervention improved executive function, self-regulation, and quality of life.

Regarding self-report inventories, the intervention group showed a greater reduction in self-reported problems with daily tasks requiring executive functions, better improvements in quality of life, larger reductions in impulsivity and greater improvements in self-control (self-regulation), controlling for baseline measures.

Influential Factors: Duration of treatment and assessment interval influenced self-regulation outcomes.

Treatment duration and the time elapsed between baseline and follow-up had a small but statistically significant effect on impulsivity and self-control, respectively; longer durations and testing intervals were associated with better scores.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

What is noteworthy about this line of substance use disorder treatment research is that the brain training strategies are not directly linked to substance use, per se. Typically, in treatment, there are obvious connections to what one is learning in treatment and its role in preventing future problems. This is different. Studies like these lend insight to potential mechanisms for enhancing treatment and provide an important foundation for future research. Executive functions are necessary for effectively regulating goal-oriented behaviors in everyday life (e.g., performing a job; budgeting finances). Rehabilitating executive functions in substance use disorder patients might also enhance self-regulation and quality of life. Although executive dysfunction often accompanies substance use disorder, this study suggests that cognitive rehabilitation programs have the potential to enhance executive function, both performance-based and inventory-based measures, and increase quality of life. Despite this improvement, performance-based executive function did not show improvement in all domains. Whereas response inhibition improved, working memory and set-shifting did not. Retraining strategies and exercises that address individual categories of executive function in greater detail may be needed to sufficiently rehabilitate all areas of dysfunction. For example, previous studies have shown that working memory retraining can decrease delay discounting (a person’s ability to forgo smaller immediate awards for larger later rewards). Nonetheless, the current study’s surveys assessing the more functional everyday aspects of executive ability showed overall improvement and quality of life significantly increased, pointing to real-world implications. Not excluding individuals for a history of head trauma or psychiatric comorbidity also prioritizes translation to realistic treatment populations, which can ultimately broaden clinical application in subsequent research.

On average, the experimental group had somewhat longer treatment durations and 5 additional days between baseline and follow-up assessment, generally warranting caution when interpreting outcomes. Given that these variables had a small but significant influence on self-reported measures of impulsivity and self-control, the effect of intervention on self-regulation is not entirely clear. Nonetheless, the suggested benefits of the intervention on inhibitory control, everyday executive function problems, and quality of life were not influenced by treatment duration or assessment interval. Therefore, this study at least demonstrates the potential for cognitive retraining programs to improve executive abilities, providing an important first step in an area of research that has great potential. Though few cognitive retraining studies have looked at recovery outcomes, those that have suggest retraining, and subsequent cognitive improvement, may be associated with improved recovery outcomes, such as reduced drug craving and substance misuse, fewer psychiatric symptoms, and improvements in self-regulation. Further research will be essential to determining the full extent of cognitive retraining’s effects on long-term recovery.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Training modules for group sessions were derived from various training programs. Although the cognitive remediation battery has been used in other clinical populations, it has not yet been tested in substance use disorder populations. Given that the efficacy of Lumosity as a cognitive remediation battery for addiction treatment populations has yet to be validated, and that the training modules were not based on a single standard program, further study is needed to determine if findings can be replicated and if remediation programs directed specifically at SUD populations may be more beneficial.

- This study was conducted with a relatively small sample of women in Australia. Additional research is needed to determine if these findings would be observed across culture, sex, and with larger populations. Given variable presentation of multiple different substance use disorders, additional investigations are needed to determine if cognitive remediation’s benefits differ by disorder.

- Given group differences in treatment duration and assessment interval, and the influence of these variables on measures of self-regulation, the effect of intervention on self-regulation is unclear. Matched-controlled designs will help clarify the effects of cognitive retraining programs on specific aspects of executive function and related processes.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Although substance use disorder patients often show signs of cognitive dysfunction, this impairment can improve, and changes might be seen regardless of other psychiatric problems and former head injuries. While cognitive retraining research is in its early stages, it is possible that these interventions can aid cognitive rehabilitation in important areas of function and have a positive impact on quality of life. Although more research is needed, learning cognitive strategies and applying them while exercising the brain could potentially help to support treatment and recovery. At the very least, these retraining programs are unlikely to hinder outcomes. If accessible, they may be worth a try. Future research will help to develop and test ideal cognitive remediation programs, and help identify who in particular is likely to benefit the most from them. This study provides a good foundation for the next steps in a promising line of work.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Addiction is accompanied by dysfunction in a variety of mental, physical, and psychosocial domains. Many of these problems can negatively impact the course of treatment and its outcomes. Addressing multiple areas of dysfunction in substance use disorder patients is necessary for a comprehensive rehabilitation approach and can ultimately benefit long-term recovery. As the first study to look at neuropsychological intervention in substance use disorder patients with psychiatric and head injury comorbidities, outcomes are encouraging and suggest that engaging patients in strategy-based training and cognitive exercise (i.e. cognitive remediation) may help to alleviate cognitive dysfunction and improve quality of life. Studies like these also lend valuable insight to treatment approaches that might be applicable to the general treatment-seeking population. Despite its promise, cognitive remediation training requires further study before it can be widely and reliably used in clinical settings. Still, it offers a promising potential avenue for enhancing treatment.

- For scientists: Executive dysfunction commonly accompanies substance use disorders, as do psychiatric comorbidities and a history of head trauma, which collectively, negatively impact treatment. This study suggests the potential for cognitive remediation programs that integrate “drill and practice” as well as “strategy based” training to enhance executive ability and quality of life in everyday functions despite comorbidity. As the first investigation of neuropsychological intervention in substance use disorder patients with psychiatric and head injury comorbidities, this preliminary work emphasizes the need for more research that prioritizes translation to realistic patient populations. It is important to examine whether current interventions can be enhanced to yield the greatest gains, and to establish a standardized, reliable, and valid program that can be used in substance use disorder research to realize the scope of its benefits. The necessary duration and schedule of training needed to reap these benefits and the treatment stages at which patients are most sensitive to intervention effects require identification via randomized control-matched investigation.

- For policy makers: Substance use disorder patients often present for treatment with cognitive deficits, psychiatric comorbidities, and medical histories indicative of prior head trauma. All of these factors can have a negative impact on treatment outcome. As a first look at neuropsychological intervention in substance use disorder patients with these common overlapping factors, this study demonstrates the potential for retraining programs to enhance functioning and emphasizes the need for additional cognitive rehabilitation research that prioritizes clinical translation to real-world patients. Studies in other clinical populations show the benefits of cognitive retraining and this study supports its potential for use in substance use disorder patients. Given national initiatives to enhance substance use disorder treatment, prevention, and recovery, additional funding is needed to explore the full potential of cognitive remediation for facilitating substance use disorder treatment outcomes.

CITATIONS

Marceau, E. M., Berry, J., Lunn, J., Kelly, P. J., & Solowij, N. (2017). Cognitive remediation improves executive functions, self-regulation and quality of life in residents of a substance use disorder therapeutic community. Drug and alcohol dependence, 178, 150-158.