Smoking interventions can help individuals in addiction treatment quit cigarettes, although questions remain about cessation effects on treatment outcomes

Many with direct professional and personal addiction experience feel that individuals with substance use disorder who smoke cigarettes should not attempt to quit at the same time they are addressing their alcohol and drug use problems. Smoking cessation efforts during addiction treatment, they theorize, could distract individuals from focusing on resolving their more immediate alcohol/drug concerns, or might increase stress, triggering alcohol/drug craving and relapse. At the same time, it is important to know which smoking cessation interventions are best for those who do, in fact, want to quit at the same time. This meta-analysis took an empirical look at how individuals with current or former substance use disorder fare in response to various smoking cessation interventions, both in terms of cigarette smoking and substance use outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

People with alcohol and other drug use disorders (i.e., substance use disorder [SUD]), are 2-4 times more likely to smoke than individuals in the general population. Health risks from cigarette smoking, of course, are numerous and well documented. Relative to heath risks and the negative impact on functioning from alcohol and other drugs like opioids, cocaine, and cannabis, however, cigarette health risks are typically far less immediate. It is possible that participation in smoking cessation interventions could dilute the focus on SUD treatment and recovery efforts, or lead to increases in stress which, in turn, could lead to increased risk for SUD relapse, which can have immediate fatal consequences. Indeed, some treatment professionals, administrators, and individuals with current or resolved substance use problems believe smoking cessation interventions may be risky if delivered at the same time people are addressing their alcohol and drug use. While many studies suggest SUD treatment participants who smoke are willing to quit cigarettes at the same time as receiving SUD treatment (i.e., simultaneous treatment), others show that, if given the choice, patients would prefer to stop smoking after their SUD stabilizes (i.e., sequential treatment). In part due to these concerns, SUD treatment programs seldom offer smoking cessation interventions, and some might even discourage individuals from attempting to quit at this critical juncture. Thus there are two important questions: 1) For individuals in SUD treatment who want to quit, what are the best strategies to help them? and 2) For those who participate in smoking cessation interventions, how does this affect their alcohol and other drug use outcomes? This systematic review published in the Cochrane Database, which requires a very high level of scientific rigor, summarized 34 studies of smoking cessation interventions among individuals with current or former SUD, to help answer these two questions.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The meta-analysis included 34 studies of 5,800 individuals aged 15 or older “undergoing inpatient or outpatient SUD treatment” or “in SUD recovery” while simultaneously participating in a study of a smoking cessation intervention. Of these 34 studies, 12 of the studies targeted individuals “in treatment” for SUD and 22 targeted individuals “in recovery” from SUD. Study authors used the terms “in treatment” or “in recovery” without defining specifically how studies were categorized into one or the other.

Authors assessed the effectiveness of psychosocial approaches (e.g., talk therapies), pharmacotherapies including nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., nicotine patch or gum), or both. They were only able to examine alcohol and other drug outcomes in 11 of these 34 studies – i.e., in 23 of the studies, the findings did not include alcohol/drug outcomes. Study comparison conditions consisted of a range of different “usual care” comparison groups including, for example, another intervention that is less intensive (e.g., brief advice or monitoring) or referral to smoking cessation programs.

Authors broke down the studies to explore whether different factors affected the results; that is, to examine if the smoking cessation intervention was more effective or impacted substance use outcomes for some types of individuals but not others (i.e., moderation effects). Of the 34 studies, 11 tested a pharmacotherapy, including nicotine replacement treatments like nicotine patches or gum, as well as prescription medications like varenicline (also known and marketed by the brand name Chantix in the United States), 11 tested psychosocial approaches which ranged widely in intensity (e.g., ranging from a single 30–minute session to 12 sessions), and 12 looked at combined pharmacotherapy/psychosocial approaches.

The primary smoking outcome was abstinence over a particular period of time (e.g., 7 days or 30 days) and the primary substance use outcome was also abstinence over a particular period of time. For both outcomes, authors looked only at the final follow-up point; that is, the longest amount of time between when participants finished treatment and when they were assessed for the last time. This final follow-up point varied widely depending on the study, but was generally about 6 months.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

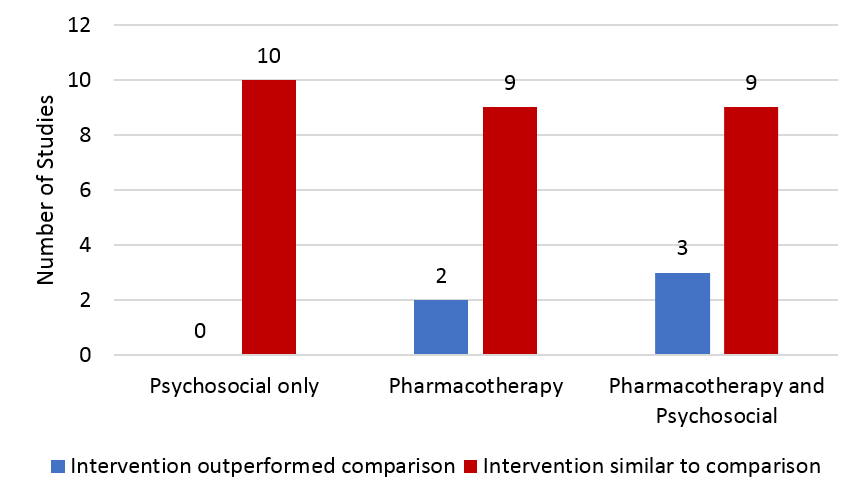

Compared to “usual care”, participants receiving smoking cessation were more likely to be abstinent from cigarettes only if the cessation intervention was pharmacotherapy, or a combined pharmacotherapy/ psychosocial approach. On average, psychosocial approaches did no better than the usual care comparison groups. The advantages for both pharmacotherapy and pharmacotherapy plus psychosocial approaches were almost 2 times greater for the smoking cessation groups. This means that someone would have a 2 times greater likelihood of being abstinent from cigarettes at the last assessment compared to those who received only usual care. One important note is that when separated out by type of pharmacotherapy, only nicotine replacement therapies (e.g., nicotine patch), and not prescription medications, were better than usual care at helping people maintain smoking abstinence. The figure below shows a count for number of studies where the intervention outperformed the comparison on smoking abstinence. The meta-analysis findings take into account how many individuals were in each study. Thus, smoking cessation intervention participants may not do any better than comparison participants in a given study. When all the studies are examined at the same time like is done in meta-analyses such as this one, we learn that, overall, the average smoking cessation participant does in fact benefit from these interventions provided that the intervention consists of pharmacotherapy or a combined pharmacotherapy/psychosocial intervention.

Note: One psychosocial study could not be analyzed due to insufficient information.

In 11 studies where substance use outcome data were reported (eight of which were “recovery” samples and three of which were “treatment” samples), participants had similar rates of alcohol and other drug abstinence irrespective of whether they received the smoking cessation intervention or usual care. When compared by type of SUD, those with alcohol use disorder who participated in smoking cessation interventions did as well as those with other drug use disorders.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This meta-analysis showed that individuals with current or former SUD who are willing to participate in a smoking cessation intervention can benefit, particularly from nicotine replacement therapies (e.g., nicotine patch) and combined pharmacotherapy/psychosocial approaches. Those who received these smoking cessation interventions had smoking abstinence rates 2 times greater than those who did not receive these interventions.

The answer to how participating in these cessation interventions affect SUD treatment outcomes is less clear, however. In the studies where alcohol and other drug use were reported (only 11 of the 34), those who received a smoking intervention had similar abstinence rates compared to those who did not – in other words, their substance use outcomes did not appear to be negatively affected by participating in smoking interventions. This is important. At the same time, it is not clear whether participants were actively participating in treatment, had active SUD (e.g., still using substances or abstinent/without symptoms less than 3 months) or were in early (3-12 months abstinent or otherwise without SUD symptoms) or sustained remission (12+ months abstinent or without SUD symptoms).

For example, in one study individuals defined as being “in treatment” had between 2 and 12 months of abstinence, and in another they had at least 1 year of abstinence. Such individuals are more readily associated with a “recovery” than “treatment” sample. On the other hand, for example, in one study individuals defined as being “in recovery” were recruited from residential treatment programs. Also, substance use outcome data from 23 of the 34 smoking cessation interventions were not analyzed because the original studies did not report these substance use data in their findings. Therefore, it is not clear if the findings from the 11 studies – where there was no effect of receiving a smoking cessation intervention on substance use outcomes – generalize to individuals in SUD treatment overall. Finally, these studies measured participants a maximum of 12 months after receiving the smoking cessation intervention, but more commonly 3-6 months later, so we do not have a good sense of the long-term effects on substance use. Taken together, these issues make it difficult to determine whether participating in smoking cessation interventions will help, harm, or have no effect on substance use outcomes for individuals in SUD treatment or early SUD recovery (e.g., within the first 3 months of change but not attending treatment).

A meta-analysis published in 2004 (12 years before this one) by Prochaska and colleagues suggested those who participated in smoking cessation interventions had slightly better substance use outcomes than those in comparison groups. While it is not possible to determine exactly what accounted for the different findings between these two meta-analyses, one possibility is that in the 2004 meta-analysis, smoking cessation participants virtually always received more treatment – including evidence-based psychosocial approaches like cognitive-behavioral therapy where they might be learning new skills they were not otherwise learning in SUD treatment. Here then, it would not be quitting smoking, per se, that is directly causing the better substance use outcomes, but rather the new skills they are exposed to via smoking cessation treatment which can also be deployed to reduce SUD relapse risk. Also, this advantage does not appear until many months after receiving the smoking cessation intervention. Therefore, when smoking cessation rates are at their highest, substance use outcomes are similar; it is not until later when this slight advantage emerges suggesting it is unlikely quitting cigarettes that leads to improved SUD outcomes.

Studies like the Prochaska meta-analysis have been used as rationale for banning cigarette smoking in some treatment programs. Overall, though, banning smoking as a policy is not an evidence-based application of the existing research on smoking cessation interventions outlined here. The data are not strong that quitting smoking helps individuals quit alcohol or other drugs. Also, of note, in many of these studies individuals wanted to quit and volunteered for a study knowing that they would be encouraged to do so. Given the selectiveness of such samples, their outcomes cannot be generalized to confirm a universal mandated smoking cessation intervention for patients that are smokers at the time of their alcohol/drug treatment. At the same time, it is possible that banning smoking in publicly funded SUD treatment programs will be a barrier to SUD treatment participation, which is particularly relevant for individuals in lower socioeconomic strata given their financial limitations in being able to access private treatment programs. This is an important empirical question for further study.

That said, the take-home message from these studies offers some preliminary good news: Individuals can be offered smoking cessation during SUD treatment without fear that this will negatively impact their substance use outcomes. This adds to other good news from a recent study conducted by the Recovery Research Institute using a nationally-representative sample of individuals in recovery from an alcohol/drug problem. Results showed that more people than ever with alcohol/drug problems are quitting cigarettes, and those who resolved their problem more recently are quitting sooner than those who resolved their problem longer ago. These findings potentially reflect changing policies and norms related to cigarette smoking.

One question not addressed in this meta-analysis was whether it might be better to wait to engage in a smoking cessation intervention until someone has stabilized in recovery from their alcohol/drug problems. One study by Joseph and colleagues in individuals with alcohol use disorder found that this was the case – it was better to wait. Another study in individuals with cannabis use disorder, however, found waiting may lead to lower engagement with smoking cessation and, therefore, a missed opportunity.

There remain some important questions around what types of smoking cessation interventions are best. Even in the studies where those receiving well-designed interventions did better than those in the comparison condition, it is difficult to help individuals with SUD quit cigarettes. For example, in the study from this meta-analysis with the largest benefit from smoking cessation, which included combined buproprion (also known by brand names Zyban and Wellbutrin), a nicotine inhaler, psychosocial counseling, as well as contingency management which rewarded individuals for cigarette abstinence, just 22% were abstinent from cigarettes for 7 days at the end of treatment. This is descriptively lower than in a smoking cessation trial for individuals without SUD or other psychiatric disorder where a group receiving buproprion and a very brief (less than 10 minute) weekly psychosocial counseling but no contingency management or nicotine replacement had 30% with 7-day abstinence. Indeed, the data in this meta-analysis suggest nicotine replacement therapies are likely to help. While psychosocial approaches on their own are unlikely to help, contingency management which rewards individuals for cigarette abstinence often help as covered in a prior Research Bulletin summary.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The strength of a meta-analysis is that authors can synthesize and aggregate the results of many studies at the same time – providing an overview of findings in a research area. This can also be a weakness, as small study differences, like the type of pharmacotherapy or psychosocial approach, can be obscured. Authors do their best to look at these factors, but often times there aren’t enough studies with enough people to examine every important question.

- The authors judged the quality of the evidence to be low because many studies did not provide enough details about the methods that they used.

- There were other limitations summarized in “What are the Implications of These Findings?” such as being able to analyze alcohol and other drug outcomes in only 11 of the 34 studies.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This meta-analysis, a study of many studies, showed that individuals in treatment for, or in recovery from, substance use disorder (SUD) can benefit from cigarette smoking cessation interventions. Nicotine replacement therapies, with or without additional psychosocial treatment like talk therapies, may work best. The available research suggests that for those willing to quit cigarettes, it is unlikely to harm their substance use outcomes, but there is insufficient evidence to indicate that quitting cigarettes can directly lead to improved SUD outcomes. Additional important questions remain, regarding how quitting cigarettes will affect SUD treatment outcomes over the long-term, and how mandated cessation or prohibiting smoking in SUD treatment programs could put some people off from accessing those programs at all.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This meta-analysis, a study of many studies, showed that individuals in treatment for, or in recovery from, substance use disorder (SUD) can benefit from cigarette smoking cessation interventions. Nicotine replacement therapies, with or without additional psychosocial treatment like talk therapies, may work best. The available research suggests that for those willing to quit cigarettes, it is unlikely to harm their substance use outcomes, but there is insufficient evidence to indicate that quitting cigarettes can directly lead to improved SUD outcomes. Additional important questions remain, regarding how quitting cigarettes will affect SUD treatment outcomes over the long-term, and how mandated cessation or prohibiting smoking in SUD treatment programs could put some people off from accessing those programs at all. At this point, it is recommended to offer individuals smoking cessation in SUD treatment and recovery support service settings while following closely how cessation impacts their substance use for those who choose to engage in smoking cessation.

- For scientists: This meta-analysis, a study of many studies, showed that individuals in treatment for, or in recovery from, substance use disorder (SUD) can benefit from cigarette smoking cessation interventions as well. Nicotine replacement therapies, with or without additional psychosocial treatment like talk therapies, may work best. The available research suggests that for those willing to quit cigarettes, it is unlikely to harm their substance use outcomes. The researchers note here that many of the studies were of low quality based on Cochrane System standards. Specifically, most studies did not provide sufficient methodological detail to assess these different biases. Additional important questions remain, regarding how quitting cigarettes will affect SUD treatment outcomes over the long-term, and how mandated cessation or prohibiting smoking in SUD treatment programs affect treatment participation. Given the public health significance of cigarette smoking among individuals in SUD treatment and recovery, these are research questions ripe for scientific investigation.

- For policy makers: This meta-analysis, a study of many studies, showed that individuals in treatment for, or in recovery from, substance use disorder (SUD) can benefit from cigarette smoking cessation interventions. Nicotine replacement therapies, with or without additional psychosocial treatment like talk therapies, may work best. The available research suggests that for those willing to quit cigarettes, it is unlikely to harm their substance use outcomes, but there is insufficient evidence to indicate that quitting cigarettes can directly lead to improved SUD outcomes. Additional important questions remain, regarding how quitting cigarettes will affect SUD treatment outcomes over the long-term, and how mandated cessation or prohibiting smoking in SUD treatment programs could put some people off from accessing those programs at all. These questions are particularly important for individuals in lower socioeconomic strata whose options for SUD treatment are limited. Policies prohibiting smoking, based on the available evidence, are premature at this stage.

CITATIONS

Apollonio D, Philipps R, Bero L. Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance use disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD010274. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010274.pub2