Routine measurement of addiction patients’ treatment response and outcomes – implications for addiction treatment

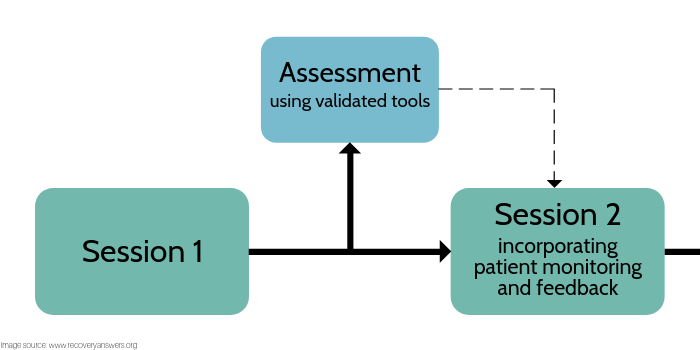

The value of using regular assessments to monitor patients’ progress in psychotherapy is well appreciated by clinical scientists. At the same time, the vast majority of treatment settings do not use such measurement. This is especially true in addiction treatment settings, which often utilize more unstructured group therapy formats and use counselors with limited formal training in empirically-supported interventions. Using a meta-analytic approach in which the authors statistically summarized the existing scientific literature on this topic, Lambert and colleagues sought to formally explore the potential benefits of routine clinical measurement, monitoring, and feedback in psychotherapy for a variety of disorders.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

While most people who attend psychotherapy will improve in terms of their functioning and subjective well-being, an estimated 5% to 10% of adults participating in psychotherapy clinical trials leave treatment worse off than they began. Also, concerningly, patients treated in clinical practice often don’t fare as well as those participating in clinical trials, most likely because standard clinical practice does not typically include built-in checks to ensure treatment is adherent to best practices. Further, even when empirically-supported psychosocial interventions for substance use disorder are disseminated in the real world, they don’t always produce outcomes better than treatment–as–usual (to read more about this, see papers from Morgenstern and colleagues and Wells and colleagues). Regularly measuring and tracking patient progress with standardized self-report scales throughout the course of treatment and providing clinicians and patients with this feedback and ways to address instances where the therapy is not “on track” may improve treatment outcomes. Though there have been a number of studies on this topic, this body of research had not been analyzed as a collective whole to test for the consistency of findings (i.e., a meta-analysis). Lambert and colleagues sought to address this gap by reviewing the work to–date and conducting a meta-analysis of reported findings. This study, while examining psychotherapy more generally among individuals with a range of disorders, could inform a similar approach for substance use disorder treatment specifically.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors focused on existing studies that utilized two widely–employed clinical tools for measuring and tracking patient progress:

- The Outcome Questionnaire-45 was conceptualized and designed to assess three domains of patient functioning, including symptoms of psychological disturbance (particularly anxiety and depression), interpersonal problems, and social role functioning. A computerized version of this measure can be used to statistically generate an expected recovery curve for differing levels of pretreatment disturbance, and uses this as a basis for identifying patients who are not making expected treatment gains and are at risk for a poor treatment outcome (starting with the second encounter). In conjunction with identifying deteriorating cases, the computerized Outcome Quesitonnaire-45 also provides a method for directing clinician problem solving with at-risk cases called the clinical support tool. The clinical support tool is composed of a problem-solving decision tree that systematically directs a clinician’s attention to factors that have been shown to be consistently related to patient outcome. A second measure, the Assessment for Signal Cases was developed to assist clinicians in going through this decision tree. The Assessment for Signal Cases is a 40-item patient self-report scale aimed at assessing the therapeutic alliance, motivation, social support, and negative life events. Rather than a total score, the Assessment for Signal Cases feedback to clinicians is provided for each assessment domain.

- The Partners for Change Outcome Management System is a routine outcome monitoring system that uses two ultra-brief scales (four items each): the Outcome Rating Scale and the Session Rating Scale. The Outcome Rating focuses on mental health functioning, modeled after the domains of outcome measured by subscales of the Outcome Questionnaire-45. The Session Rating Scale is designed to assess the therapeutic alliance. Because of its brevity, this system is clinician–friendly and allows ratings of mental health status and therapeutic alliance to be typically collected in the presence of the therapist. This facilitates the discussion of assessment results by the patient and therapist in session.

The authors reviewed studies that met all of the following eligibility criteria: (a) use of Outcome Questionnaire System or Partners for Change Outcome Management System for providing mental health feedback, (b) the intervention was provided to a mental health sample (without restrictions on diagnoses), (c) the intervention provided was a recognizable psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and eclectic psychotherapy) with no restrictions on treatment setting or modality (individual, group, and couple), and (d) patients were assigned (not necessarily randomly) either to a psychotherapy with feedback condition or to a psychotherapy without feedback condition. Additionally, to be included in the meta-analysis, studies needed to report patient outcomes and statistics needed for calculating treatment effects.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review of the Outcome Question System

Of the 15 identified studies reviewed, 11 (73%) found a statistically significant difference between the assessment and feedback group, and the treatment–as–usual control on the primary outcome variable (Outcome Question-45). The practical implication of this finding is that clinics and practitioners are highly likely to find implementing feedback in routine care will reliably enhance patient outcomes for patients who are not–on-track (i.e., about one-third of most clinician’s caseload).

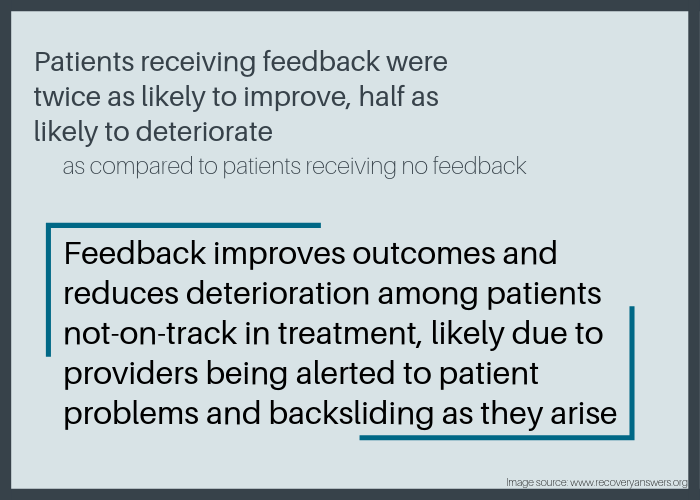

Meta-analysis of these 15 studies showed that the progress feedback intervention outperformed treatment–as–usual in the total sample by a very small but statistically significant effect at the end of the treatment. Results showed, however, that the Outcome Question System feedback did not reduce the number of patients who deteriorated, or increase the number of improved patients at the end of therapy, compared to treatment–as–usual (i.e., no assessment or feedback). Perhaps not surprisingly, the effects were better when the authors focused on patients who were clinically not-on-track (i.e., not improving in treatment or predicted to have poor outcomes). The meta-analysis showed that these patients receiving feedback were about half as likely to deteriorate versus those receiving no feedback, and were almost twice as likely to improve. In other words, feedback appears to prevent patient deterioration and improve outcomes for patients who are not–on-track in treatment, most likely because treatment providers are being alerted to patient problems and backsliding as they arise.

Figure 2.

Of the eight studies utilizing the clinical support tool, the analyses showed a significant benefit of feedback plus a clinical support tool on the rate of deteriorating patients, with those receiving feedback plus a clinical support tool being approximately two-thirds less likely to deteriorate. Feedback with the clinical support tool was also associated with higher rates of improvement, with those receiving feedback plus clinical support tool being 2.4 times more likely to improve.

Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review of the Partners for Change Outcome Management System

Across the nine studies reviewed, six (67%) reported a statistically significant difference between Partners for Change Outcome Management System feedback and treatment–as–usual conditions. That is, patients receiving Partners for Change Outcome Management System assessment and feedback fared better than those getting treatment–as–usual (i.e., no assessment or feedback).

The meta-analysis of nine studies showed that the Partners for Change Outcome Management System shows a statistically significant and small-to-moderate benefit in comparison with the treatment–as–usual across the studies assessed. The Partners for Change Outcome Management System feedback, however, does not have a significant benefit in contrast to treatment–as–usual on reducing the number of deteriorating patients (OR= .97), although those receiving feedback were approximately twice as likely to improve (OR= 2.11). It should be noted, though, that the clinical results appeared to vary as a function of patient, clinician, and/or method variations. Within this set of nine studies, four were conducted outside of the United States and three of these studies did not show an advantage for feedback.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings from this review and meta-analysis support the use of routinely and formally measuring and monitoring patients’ engagement with treatment and their psychological state as they undergo a course of psychotherapy, particularly for individuals who are not faring well in therapy.

Implementation of assessment and feedback may double patients’ chances of improvement, which represents a massive gain for very little expenditure, both in terms of time required and cost. Evidence supports the Outcome Questionnaire System and the Partners for Change Outcome Management System with adults across treatment modalities (e.g., individual, couple, and/or group) and clinical settings, although other monitoring systems with similar features may be equally as effective.

Broadly speaking, the use of recovery outcome management systems can alert clinicians to patient risk and help detection of patient worsening in psychotherapy. Further, systems like the Assessment for Signal Cases and Clinical Support Tool can serve as vital signs of patient progress and be useful for eliciting provider/patient discussions in session.

This review and meta-analysis was not focused on substance use disorder per se, although results are also applicable to addictions treatment. The findings here suggest that, for substance use disorder patients most at risk for poor treatment response, a suite of clinical tools including patient outcome monitoring, feedback to patient and clinician, and associated clinical support tools would likely improve outcomes and could make a measurable difference in patients’ lives.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The body of research reviewed relies solely on single self-report measures. That is, objective measures confirming participants’ self-report were not included. Thus, there is risk that participant bias may have affected results.

- Relatedly, across all the studies reviewed here is that the same measure was used to track progress and to quantify the end-of–treatment outcome. Although it would be ideal to assess mental health status at the beginning and end of treatment using several standardized measures, this was rarely done. As a result, effect sizes reported here may be inflated.

- Limiting the literature search to the English language may mean studies were missed.

- The authors of this review and meta-analysis were also responsible for the development of the Outcome Question-45, which represents a conflict of interest, thus introducing some risk for bias.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The authors’ findings highlight the importance of regular assessment to monitor the progress of treatment, and the value of providing this information as provider/patient feedback. Currently this is not widely practiced in addictions treatment, except perhaps in some higher quality programs. When looking for treatment programs, ask if patient progress is routinely assessed using standardized measures.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The authors’ findings highlight the importance of regular assessment to monitor the progress of treatment, and the value of providing this information as provider/patient feedback. Currently this is not widely practiced in addictions treatment. Integrating regular assessment of patient engagement with treatment and treatment progress, and providing this information as provider/patient feedback has the potential to markedly improve patient outcomes.

- For scientists: The authors’ findings highlight the importance of regular assessment to monitor the progress of treatment, and the value of providing this information as provider/patient feedback. Currently, this is not widely practiced in addictions treatment. Future research needs to be conducted across a wider range of treatment settings and patient populations, thus illuminating the limits of these practices and clarifying the factors that maximize patient gains. Future research should also test whether such an approach improves patient outcomes specifically in substance use disorder treatment relative to treatment–as–usual.

- For policy makers: The authors’ findings highlight the importance of regular assessment to monitor the progress of treatment, and the value of providing this information as provider/patient feedback. Currently, this is not widely practiced in addictions treatment. Policies requiring this kind of monitoring have the potential to improve treatment outcomes, and as a result, public health. Such policies also have the potential to bring down managed care costs by improving treatment and creating better provider accountability.

CITATIONS

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 520-537. doi: 10.1037/pst0000167