Who is most likely to try nicotine replacement therapy while in addiction treatment?

Substance use disorder treatment programs may be able to help patients who smoke cigarettes and want to quit by incorporating smoking cessation treatment into their usual care. These individuals, however, tend to respond poorly even to state-of-the-art smoking cessation interventions. In this study, authors explored what factors were associated with using nicotine replacement therapy to improve how smoking cessation is offered and delivered in addiction treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Cigarette and other tobacco use are very common among individuals with substance use disorder, which increase their risk of disease and premature death. However, individual- and service-level barriers often impede individuals’ access to smoking cessation treatment while in substance use disorder treatment. Better understanding of how to reduce these barriers and whether integrating smoking cessation services into addiction treatment improves the uptake of these services (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy) remains a high priority.

Nicotine replacement therapy is the recommended first-line pharmacological treatment for smoking, and successful quit attempts improve when multiple forms of nicotine replacement therapy are used (e.g., patches, lozenges) – referred to as combination nicotine replacement therapy. Some have questioned whether individuals should attempt to quit smoking at the same time that they are addressing their alcohol and other drug use (i.e., substance use). Existing evidence, however, shows that smoking cessation, including the use of nicotine replacement therapy, during addiction treatment either does not affect substance use treatment outcomes or enhances treatment outcomes. So, for those who want to stop smoking during substance use treatment it doesn’t seem to hurt and may even help. Notably, though, research has not shown conclusively that quitting smoking causes enhanced substance use outcomes. There is also evidence to support that those in addiction treatment are motivated to quit smoking, which suggests that treatment substance use treatment programs are a potentially opportune way to reach and support people who are interested in quitting. Addiction treatment patients who smoke, however, tend not to respond as well as other types of smokers to empirically-supported smoking cessations interventions. That said, the use of nicotine replacement therapy in addiction treatment programs is inconsistent and often precluded by several barriers, such as access to training and support to provide smoking cessation treatment. Research on factors that make people more or less likely to engage with these cessation interventions can inform their content and how they are delivered in real-world settings (i.e., dissemination/implementation research). Improving the integration and effectiveness of smoking cessation services within addiction treatment would provide more comprehensive care for individuals who want to quit smoking while also addressing their substance use disorder.

Guillaumier and colleagues randomized 32 substance use disorder treatment programs in Australia to receive and implement either a nicotine replacement therapy based smoking cessation treatment or to continue care as usual. Findings from this initial study found that the comprehensive smoking cessation intervention delivered to patients in 17 programs and care as usual delivered to patients in 15 programs produced similar smoking cessation outcomes, with about 2% of patients with 7-day smoking abstinence, overall, in the short-term and 0% over the long-term. In the present study, the research team performed additional analyses on these participants to examine individual- and service-level predictors of nicotine replacement therapy use among patients enrolled across the entire group of 32 programs.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

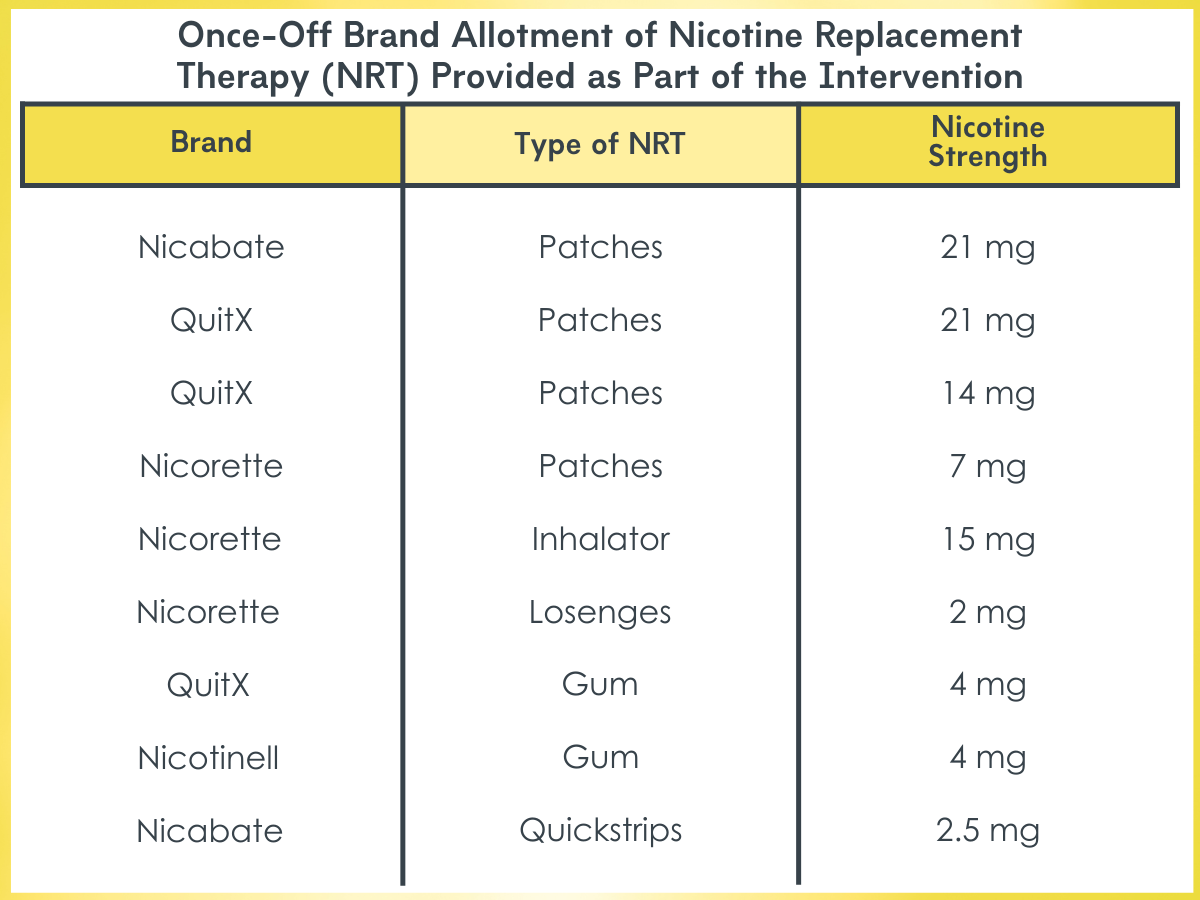

This study was part of a cluster randomized controlled trial in 32 addiction treatment programs in Australia, which were initially randomized to participate in a 12-week intervention program or to provide usual care (control group). All programs assisted with the recruitment of eligible clients who then completed online surveys at baseline (n=896), 8-week follow-up post-baseline (n=471), and 6.5-month follow-up post-baseline (n=427). Programs in the intervention group were provided free nicotine replacement therapy products and the resources and training needed to provide smoking cessation treatment. The current study was a secondary data analysis of that randomized controlled trial, including patients from all 32 programs – both intervention and control – to identify factors related to use of nicotine replacement therapy and other smoking cessation resources.

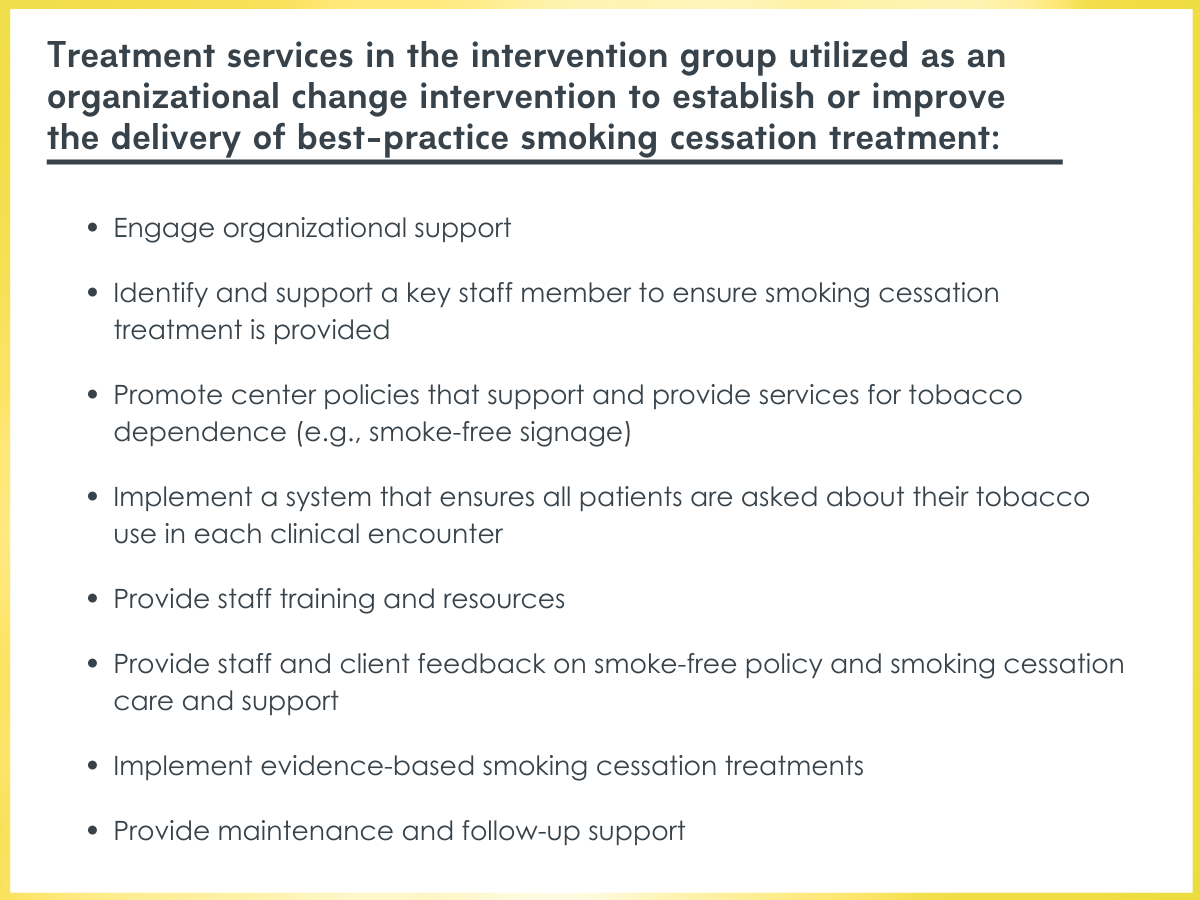

Treatment services utilized by programs in the intervention study condition.

The research team tested whether age, gender, Indigenous status, education, nicotine dependence severity, motivation to quit, intentions to quit, cessation self-efficacy, treatment program type (residential rehabilitation, counseling, opiate treatment program, or “other”), and intervention arm (intervention vs. control group) – all collected at baseline – predicted each of two outcomes: 1) any nicotine replacement therapy use and 2) combination nicotine replacement therapy use at 8-week and 6.5-month follow-ups. Notably, follow-up rates at 8-weeks and 6.5-months post-baseline were low (53% and 48%, respectively), which may introduce bias. Analyses to determine which factors were associated with nonresponse at each follow-up were not conducted (e.g., age, education, severity of nicotine dependence), so study findings should be interpreted considering this limitation. See Implications and Limitations below for more detail on follow-up rates.

Types of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) provided as part of the intervention.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Use of nicotine replacement therapy decreased over time.

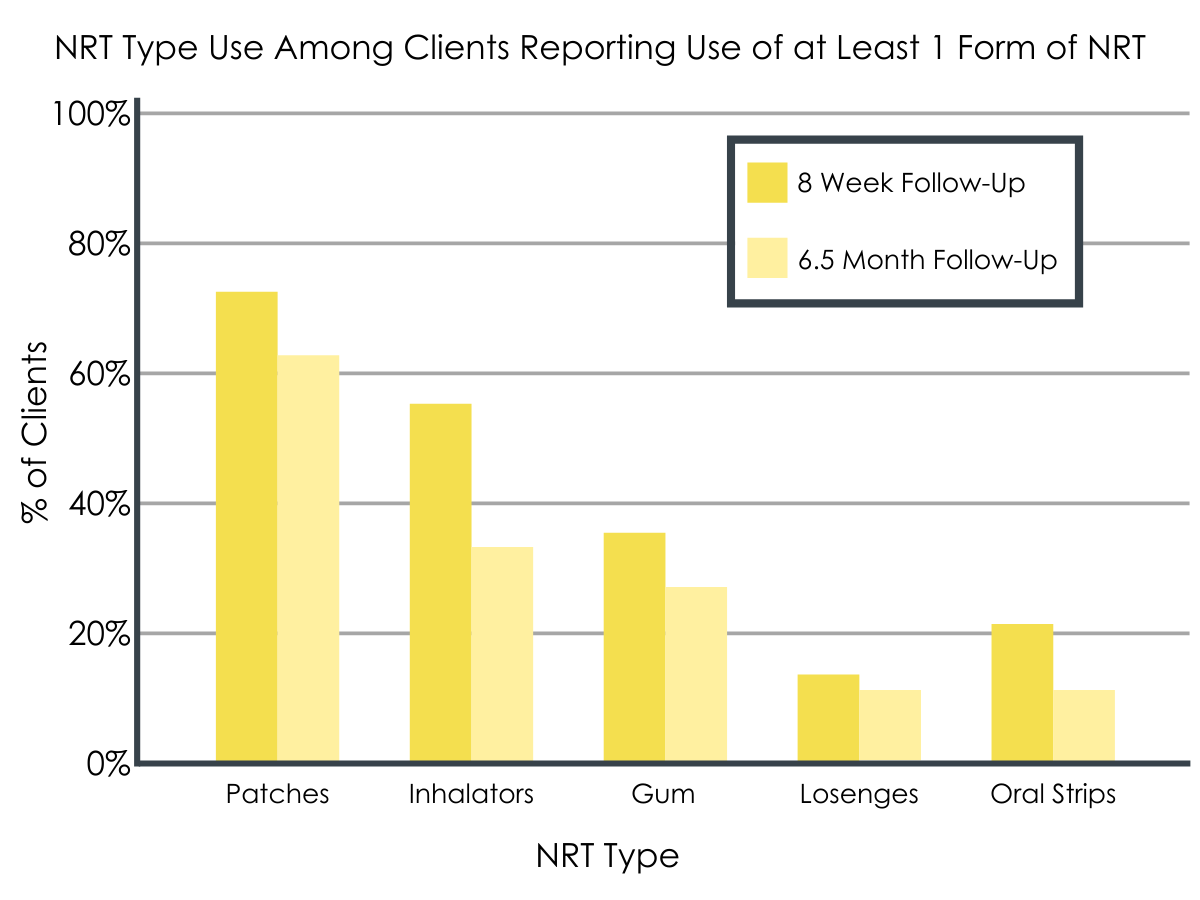

At 8-week follow-up, 57% of participants reported using any form of nicotine replacement therapy. Of those, 51% also reported combination nicotine replacement therapy use. The use of nicotine replacement therapy was reduced at the 6.5-month follow-up, with 33% of participants reporting using at least one form. Of those, 45% endorsed using combination nicotine replacement therapy. At both timepoints, patches were the most popular form of nicotine replacement therapy, followed by inhalators and gum.

NRT type use among clients reporting use of at least 1 form of NRT.

Predictors of nicotine replacement therapy use.

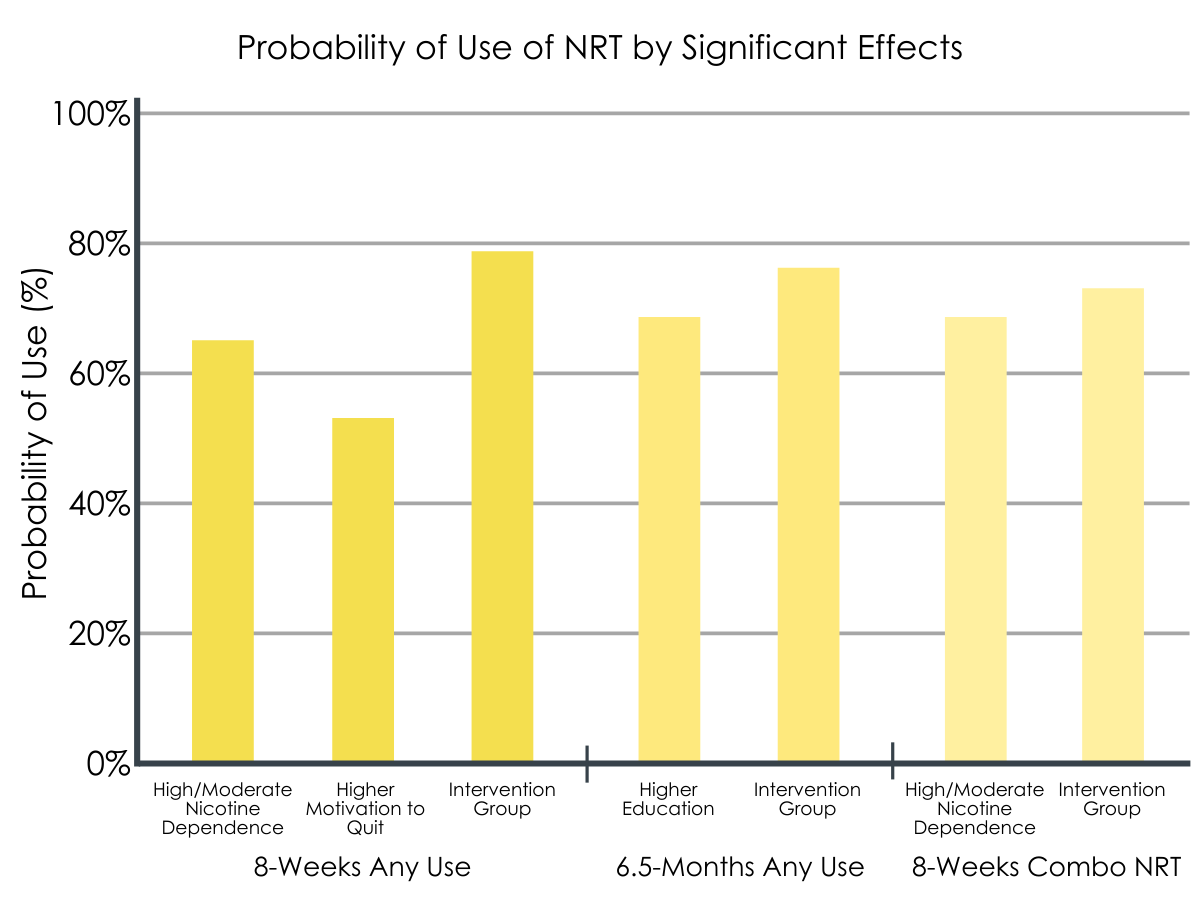

Participants were more likely to use at least one form of nicotine replacement therapy at 8-week follow-up if they were from an intervention service (vs. control service), had higher levels of nicotine dependence, or were more motivated to quit. Any use of nicotine replacement therapy at 6.5-month follow-up was predicted by being in an intervention service or greater levels of education.

Being in an intervention service or having higher nicotine dependence also predicted using combination nicotine replacement therapy at 8-week follow-up. However, no factors were associated with combination nicotine replacement therapy at 6.5-month follow-up.

Probability of use of NRT by significant effects.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The study by Guillaumier and colleagues showed that an organization change intervention that provides nicotine replacement therapy and the associated structural support and training to addiction treatment programs can improve the uptake of nicotine replacement therapy. Individuals in both control and intervention services reported using nicotine replacement therapy at both follow-up surveys, though intervention services were more likely to endorse nicotine replacement therapy uptake – both any form of use and combination therapy. That said, few participants in this study quit smoking, including those receiving and using the provided smoking cessation services.

Encouragingly, patients with more severe nicotine dependence were consistently more likely to initiate nicotine replacement therapy, suggesting that clients who are heavy smokers and in need of more cessation support may be more motivated to use the additional care provided when available. This notion is also consistent with the Health Belief Model, which describes that a person’s beliefs about the seriousness of a disease can lead to acting upon these feelings to reduce their risk – in this case, the uptake of nicotine replacement therapy. Education level was also related to nicotine replacement use at 6.5-month follow-up, but this finding was not found at the 8-week follow-up. Because it is an inconsistent finding, with the 6.5-month follow-up asking about the time period covered also at the 8-week follow-up, it is difficult to fully unpack this potential relationship.

Notably, participants in this study by Guillaumier and colleagues ultimately had very low rates of smoking abstinence, regardless of whether they were in the intervention or control group. Thus, there is a disconnect between improving the uptake of nicotine replacement therapy among individuals in substance use disorder treatment and the fact that uptake of nicotine replacement therapy alone does not seem to improve smoking cessation outcomes. Taken together, these findings indicate alternative approaches may be necessary to maximize the benefit of integrating smoking cessation services into addiction treatment (e.g., focusing on individuals who are motivated to quit smoking). For example, social mechanisms of behavior change may help promote sustained cessation efforts over time, as one study found that participants who chose to engage in an online discussion forum related to smoking cessation had greater 30-day smoking abstinence rates. Incorporating smoking cessation services into different settings (e.g., recovery community centers), other than addiction treatment programs, may also be an effective way to reach people who are motivated to quit smoking as many smokers with substance use disorder prefer to stop a little while after stabilizing in their substance use recovery. This option may be particularly beneficial to reach individuals in recovery, as evidence shows that people who have addressed their substance use disorder often quit smoking sooner.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Response rates at 8-weeks (53%) and 6.5-months (48%) were low, which may introduce bias. Further, analyses were not conducted to determine which factors (e.g., age, education) may be associated with nonresponse.

- Findings from this study are limited to the uptake of nicotine replacement therapy among individuals in addiction treatment. Data on rates of smoking cessation from this work are presented elsewhere.

- The research team acknowledged that participants were using nicotine replacement therapy tools with insufficiently low levels of nicotine according to guidelines for its clinical effectiveness. This suggests a need for improving staff training and education in this area in future iterations of this organization change intervention.

- Individuals receiving treatment from a control group service did not receive free nicotine replacement therapy, which limits the utility of comparing the uptake of nicotine replacement therapy in intervention vs. control services.

BOTTOM LINE

An organization change intervention was used to provide nicotine replacement therapy and the necessary training and support needed to implement smoking cessation care into addiction treatment services. The researchers found that over half of clients seeking treatment for substance use disorders used some form of nicotine replacement therapy at 8-week follow-up, and of those, half used combination nicotine replacement therapy – the most effective form. A third of clients used any form of nicotine replacement therapy at 6.5-month follow-up, and among those, slightly less than half used combination therapy. Receiving treatment from an intervention service, having more severe nicotine dependence, and endorsing greater motivation to quit predicted any use of nicotine replacement therapy use at 8-week follow-up, but only level of nicotine dependence and being in an intervention service were predictive of using combination therapy. However, despite the significant uptake of nicotine replacement therapy in the intervention group, and consistent with the bulk of research showing poor response to first-line smoking cessation treatments in this population, smoking abstinence rates were ultimately very low and no different across both intervention and control groups. This suggests uptake of nicotine replacement products by themselves is not enough. Developing and testing novel, innovative approaches or targeting specific groups most likely to benefit may be the next best steps for smoking cessation in substance use disorder treatment research.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Individuals who are seeking addiction treatment and also smoke cigarettes and are motivated to quit could benefit from a treatment program that integrates smoking cessation care into their usual care, particularly services that provide nicotine replacement therapy to their clients. This ideally would also include a program that could assist with securing nicotine replacement therapy post-discharge (if applicable). However, it is also important to know that, to date, the outcomes (e.g., smoking abstinence) of receiving nicotine replacement therapy alone are poor, and individuals may need added supports to increase their likelihood of sustaining smoking abstinence over time.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Findings from the present study show that integrating smoking cessation services into addiction treatment may increase the use of nicotine replacement therapy; however, this alone ultimately did not lead to improved smoking abstinence rates. Some alterations could be considered in future iterations of this organizational change intervention to improve its effectiveness. For example, it may be beneficial to connect patients to Quitline to support their cessation efforts in addition to providing nicotine replacement therapy. It may also be beneficial for programs to expand the organization intervention model presented here to ensure that patients are up-taking a clinically effective dose of nicotine replacement therapy. That said, because smoking abstinence rates were very low among these participants, it is also important to consider the resources devoted to integrating smoking cessation services. Alternative approaches could be considered to maximize its benefit, which may include introducing patients to smoking cessation, enhancing their attitudes toward quitting at a later date, or focusing on their smoking cessation expectancies. Different settings, other than substance use disorder treatment programs, could also be considered for targeted smoking cessation, particularly community and clinical services that are used by individuals in substance use disorder recovery. People in recovery often quit smoking sooner after they resolve their substance use disorder, so providing smoking cessation services outside of treatment programs would increase access these services and also reach people who are well positioned for smoking cessation.

- For scientists: In this study, the research team used a rigorous cluster randomized controlled trial design with 32 addiction treatment services. However, the level of nonresponse at each follow-up has the potential to threaten both external validity (i.e., reduces the generalizability of these findings to those who completed follow-up) and internal validity (i.e., if study drop-outs with worse nicotine replacement therapy uptake were more likely to be in the intervention, the intervention effect might be due to attrition rather than the intervention itself). Thus, replication of this research with improved response rates is needed to identify the factors associated with the uptake of nicotine response therapy while in addiction treatment. Better understanding of the reasons why some individuals used one form of nicotine replacement therapy while others used multiple, which is more clinically effective, would inform future iterations of this organizational intervention. This is a potential avenue for future research. Another fruitful area of research would be to expand the organizational intervention and randomize various levels of smoking cessation care provided (e.g., fully integrated into care, available but not integrated into care), which would help guide policy makers to support the level of integration needed to maximize its effectiveness in supporting smoking cessation. However, because smoking abstinence rates were ultimately very low in this sample, future research could consider focusing these efforts on individuals who are motivated to quit smoking, which would provide treatment programs a better understanding of how to most effectively target and help individuals in addiction treatment who also want to quit smoking.

- For policy makers: Additional funding is needed in this area to ensure that settings providing addiction treatment services are equipped to integrate smoking cessation care and support clients who are also motivated to quit smoking. Health care systems could facilitate this dissemination of care by ensuring that sufficient staff are available to support this integration. Funding dedicated to research that improves upon the current approach of providing nicotine replacement therapy alone may ultimately lead to improved smoking cessation in addiction treatment.

CITATIONS

Guillaumier, A., Skelton, E., Tzelepis, F., D’Este, C., Paul, C., Walsberger, S., . . . & Bonevski, B. (2021). Patterns and predictors of nicotine replacement therapy use among alcohol and other drug clients enrolled in a smoking cessation randomised controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors, 119: 106935. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106935