Continuing care for adolescents – can telephone support by non-professionals help?

Adolescents are at high risk for dropping out of treatment, and even among those who do complete an initial period of treatment, most return to problematic substance use. Experts increasingly recognize the importance of “continuing care”– some type of support, which could be either professional or non-professional support that follows the primary treatment episode – to help adolescents maintain and build on gains made during initial treatment. Yet there are critical barriers that make it difficult for adolescents to obtain post-treatment recovery support. This study was a randomized trial that tested the effectiveness of an innovative continuing care approach that leveraged young adult volunteers to support adolescents by phone after residential treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The importance of providing continuing care to support long-term recovery from problematic substance use is increasingly being recognized. Adolescents in particular are a high-risk patient population, as they are particularly likely to return to problematic substance use following treatment. Unfortunately, they also face unique challenges in engaging with ongoing recovery support. Continuing care can be delivered clinically (i.e., in an outpatient setting) or via recovery support services, which may be delivered by professionals or non-professionals, such as mutual help groups (e.g., AA, SMART Recovery), recovery coaching, recovery high school services, collegiate recovery programs, or recovery community centers. For adolescents, the challenges that arise in engaging with recovery communities is the fact that many of these recovery support services do not explicitly target adolescents (e.g., recovery coaches may not have expertise working with adolescents, AA members tend to be older, with few adolescent members, thereby decreasing the peer-to-peer experience for adolescents), or that they may not be physically near them (e.g., there are only 40 recovery schools in the US). To overcome these barriers, Dr. Mark Godley and colleagues designed and evaluated a continuing care program that used briefly trained, non-professional volunteers to provide ongoing support via phone calls to adolescents leaving residential SUD care.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

403 adolescents (aged 12-20, most <17 years of age) attending at least 7 days of residential substance use disorder treatment at one of four treatment centers in Arizona and Illinois in the United States, were randomized to receive either “service as usual” or Volunteer Recovery Support for Adolescents (VRSA) in addition to service-as-usual after leaving residential treatment. Service-as-usual differed somewhat between treatment centers, but generally consisted of recommendations to participate in continuing care at an outpatient program in the adolescent’s home community as well as utilizing other recovery support services, such as mutual–aid groups. Oftentimes, residential treatment providers made the first continuing care appointment with patients to increase the likelihood that they might attend these services.

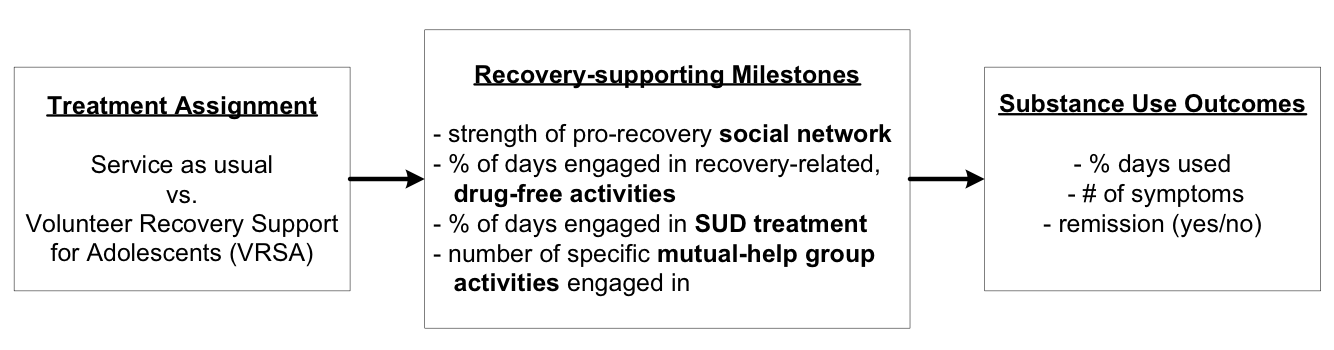

In addition to this level of continuing care linkage, VRSA provided additional check-in phone calls for an extended period of time. More specifically, VRSA was designed to add 9 months of continuing care to approximately 3 months of residential care. Participants in this group received weekly phone calls from health and human services students (who were 23 years old, on average, and received one 6-hour training session) for the first 3 months following discharge. After 3 months, the frequency of the phone calls was adjusted based on need, with a minimum of one call every other week. Phone calls were conversational in tone, lasted 15-20 minutes, encouraged spending time in substance-free pro-recovery activities and probed about substance use. Outcomes of interest (Figure 1) included both short-term goals that are predictive of sustained recovery (i.e., strength of the pro-recovery social network, engagement in sobriety related activities, engagement in SUD treatment, and level of involvement in mutual-help activities, e.g., speaking during meetings, having a 12-step sponsor) and substance-use specific outcomes.

In this study, the effect of VRSA on three substance use outcomes was evaluated: (1) the percentage of days adolescents reported using substances during the past 90 days, (2) the number of symptoms adolescents reported experiencing in the past month, using a checklist of symptoms of substance use disorder and substance-induced health and psychological disorders, and (3) whether or not they reached ‘remission’, which was defined as living in the community, being abstinent from all drugs and alcohol for the past month, and experiencing no substance use related problems. Adolescents were assessed at intake to residential treatment, and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after residential discharge.

Figure 1. Process by which VRSA was expected to support recovery from substance use problems.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

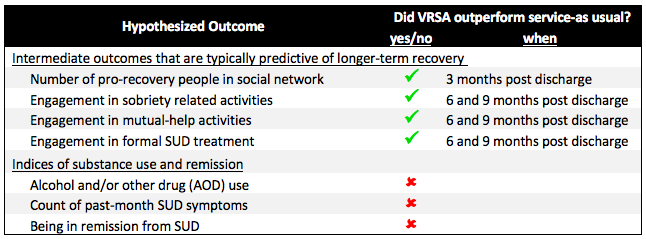

The two groups differed on indices that are typically predictive of sustained recovery, but not on substance use indices (Table 1). Namely, compared to standard care, participants who received VRSA phone calls reported a greater increase in the number of pro-recovery people in their lives, spent more time in drug-free sobriety activities, and engaged more in formal SUD treatment and mutual help group activities. The groups did not differ in terms of AOD use, experiencing substance problems, or achieving remission.

Effects were identified, however, that underscore the importance of the short-term milestones that were assessed. Namely, increases in the number of pro-recovery people in one’s network predicted decreased AOD use, which in turn predicted fewer substance use problems. Increased engagement in recovery management activities, both formal treatment and mutual-help groups, predicted increased rates of remission. The study also found a positive relationship between the number of calls completed by participants in the VRSA continuing care and both short-term milestones and substance use outcomes, but it is unclear if these effects are due to a dose-response relationship between VRSA engagement and recovery outcomes, or simply a reflection of greater recovery commitment in adolescents actively using VRSA.

Table 1. Effect on hypothesized outcomes (VRSA vs. control)

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

While the benefit of providing long-term continuing care for SUDs is increasingly recognized, many barriers exist to providing and accessing such care, particularly for adolescents. The Godley study reported promising effects for a relatively low-cost, low-barrier continuing care program. Importantly, in this approach, relatively young, but health-services interested non-professionals (i.e., health care undergraduate students) delivered care, using informal phone calls. The results of this study underscore the feasibility of providing support using non-professionals, and engaging substance using adolescents remotely via phone for a protracted period of time. Surprisingly, the effectiveness of this program was not clearly demonstrated, given the lack of group differences on substance use and remission, but effects on shorter term indices typically indicative of recovery are promising. Nevertheless, this suggests that the process of behavior change leading to reduced substance use and remission for adolescents may be different than what might be expected and current theory would predict. Specifically, while the VRSA intervention did in fact increase what was thought to be important intermediate milestones that would ultimately result in higher remission rates (e.g., increases in more recovery supportive peers in their social network and increased mutual-help activities etc., see Table 1), better substance use outcomes were not observed, even though the intermediate variables did increase. Consequently, the theory underlying youth behavior change may need closer scrutiny and more accurate specification to understand more about the factors that are driving remission among youth.

Other continuing care options for adolescents that have been tested include text messaging and check-in sessions delivered in person or via phone. Regarding text-messaging, Gonzales and colleagues conducted a pilot study in 80 adolescents and young adults and found that adolescents receiving 12-weeks of daily text messages – including monitoring, encouragement, and recovery activity facilitation messages – were less likely to have a positive urine test for their primary drug of choice, more likely to participate in recovery-related behaviors, and reported greater confidence in abstaining from substance use during recovery. Kaminer and colleagues tested a 5-session active aftercare intervention in 177 adolescents, which was delivered in person or via phone, and found a lower risk of relapse in the active aftercare condition. The Godley study adds to this literature by testing an intermediate treatment option between these two models, where VRSA is less automated than the text-messaging intervention tested by Gonzales and more conversational than the 5-sesssion treatment tested by Kaminer. The Godley study is also the largest RCT to date on testing a continuing care option for adolescents.

- LIMITATIONS

-

The Godley study was a large scale, multi-site randomized controlled trial, which is the gold standard for testing the effectiveness of a treatment. Limiting generalizability of the study findings were two main issues: (1) study participants were recruited from residential treatment programs that were strongly 12-step based; outcomes may be different in settings with a less 12-step supportive structure. (2) Very few female participants were included in the study (65 female adolescents, 16% of the sample). While reflective of the overall prevalence of SUD, it nevertheless limits insights into whether or not this treatment approach worked similarly in male and female adolescents, which is particularly relevant here, as sex differences in response to continuing care for adolescents have been noted previously.

There were also a few limitations particularly relevant to other scientists. These include the fact that this trial does not appear to have been registered prior to recruitment on ClinicalTrials.gov, as is typical practice for large-scale RCTs; no single primary outcome was defined, possibly making results vulnerable to increases in “false positive” results due to running multiple statistical tests; and a less than state-of-the-art approach was used to address missing data (i.e., median replacement), although this is a minor concern given the study’s excellent retention rate (≥93% at each assessment).

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: Continued support after residential treatment is important, especially for adolescents, who are at high risk of relapse. This support can take many shapes – formal outpatient treatment, engagement with mutual-help groups, and/or working with recovery coaches, to name just a few. This study shows that even brief, conversational phone calls with non-professionals can help engage adolescents in recovery supportive behaviors. Whether or not increases of these behaviors ultimately result in improved substance use outcomes remains to be seen. In adults, current evidence suggests that it should. The lack of findings in this study, however, raise the question if the same is true for adolescents. Keep in mind that participants in this study were participating in inpatient care, which suggests a high severity profile. Improving recovery-related behaviors may be more effective in less severe cases. Apart from the promise of this specific treatment approach, results underscore that continuing care can take many shapes, thereby providing many options to find the right match. Be sure to ask your treatment program (or treatment programs you are considering) about the continuing care options they recommend or directly help provide linkage for as part of their discharge planning. Providing linkage to continuing care is a good indicator of quality treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Continued care cannot be achieved solely via formal treatment due to finite clinical resources available in U.S. health care systems. Fortunately, a growing number of options are emerging that can help provide additional recovery support, including online and mobile supports. It may be helpful to help patients explore existing options to help them identify approaches that may work for them.

- For scientists: Adolescents continue to be a high-risk group, who face many barriers in obtaining continued recovery support over a longer period of time. While promising, the Godley findings call for more research to test if this (or a similar/enhanced) approach can impact downstream substance use outcomes, or if other intermediate milestones need to be targeted to produce improved substance use outcomes in this population. Note that the present study involved relatively high severity patients (i.e., patients participating in residential treatment), and theorized mechanisms of behavior change may well work as hypothesized in less severe adolescents. More research on this issue is necessary. Further research is necessary to test different treatment approaches, which may leverage and combine different types of interactions (e.g., in-person, phone, video, website, app, texting). Given that the goal is to provide long-term continuing care to cut short the chronic, relapsing nature of substance use disorder, the question of dose is a particularly important one to address in this context (e.g., how long should support last? How frequent should it be?)

- For policy makers: Providing continuing care for adolescents with SUDs is made difficult by several challenges, but even relatively low-cost approaches (e.g., phone calls from non-professionals) can make an important difference. Despite this, however, youth substance use outcomes in this large study did not improve more than regular continuing care as usual. This was a more severe residential sample of treated youth; testing in less severe outpatient samples remain to be studied to determine whether such an approach as VRSA can make a difference there.

CITATIONS

Godley, M. D., Passetti, L. L., Hunter, B. D., Greene, A. R., & White, W. L. (2019). A randomized trial of Volunteer Recovery Support for Adolescents (VRSA) following residential treatment discharge. J Subst Abuse Treat, 98, 15-25. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2018.11.014