How might dialectical behavior therapy work for individuals with addictive behaviors?

Individuals with alcohol use disorder sometimes also struggle with behavioral issues like gambling problems, compulsive shopping and sexual behavior, and restrictive or binge eating. Dialectical behavior therapy—a treatment originally developed for individuals with borderline personality disorder—has shown evidence that it may also be effective for the treatment of alcohol use disorder, most likely because it provides individuals with skills that help them tolerate distress, improve emotion regulation capacity, and cultivate mindfulness. The authors of this paper explored whether dialectical behavior therapy treatment for alcohol use disorder may also lead to reductions in commonly co-occurring behavioral issues.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

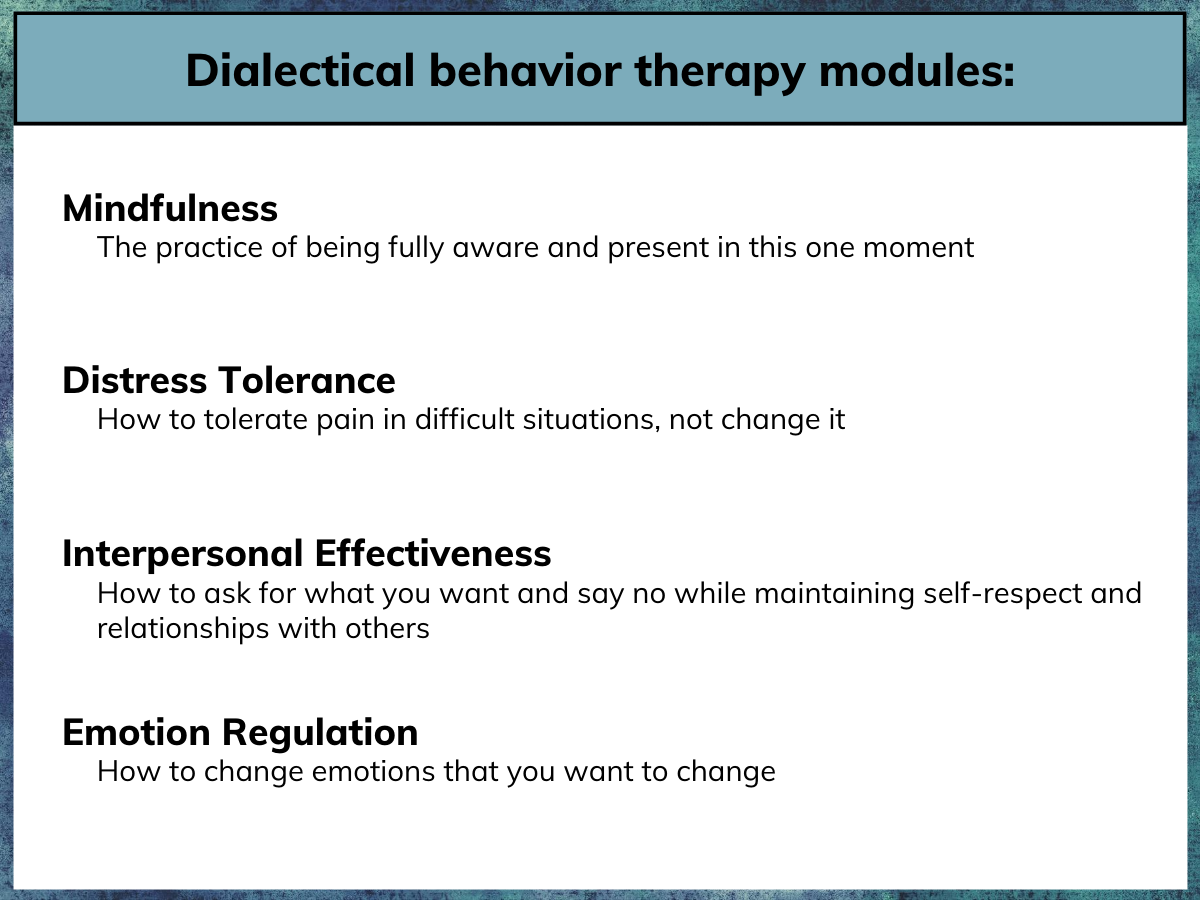

The adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy for alcohol and other substance use disorders was born out of evidence that patients with borderline personality disorder who were treated in this modality showed notable decreases of substance use behaviors. According to the dialectical behavior therapy model, reductions of harmful behaviors, including substance use, are linked to improvements in emotion regulation arising from the learning of cognitive and behavioral skills. Classic dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) includes four psychoeducational modules taught in a group format in combination with individual therapy. The modules are: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Though treatments like DBT are usually used to target specific conditions (e.g., borderline personality disorder, alcohol use disorder), this treatment may ultimately affect common underlying transdiagnostic causes and conditions, and thus could have general effects that lead to improvements in other domains. Based on this, the authors of this study, analyzed whether DBT treatment for alcohol use disorder might also give rise to improvements in a range of behavioral issues like problem gambling, compulsive shopping and sexual behavior, and restrictive and binge eating— issues that sometimes co-occur with alcohol use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

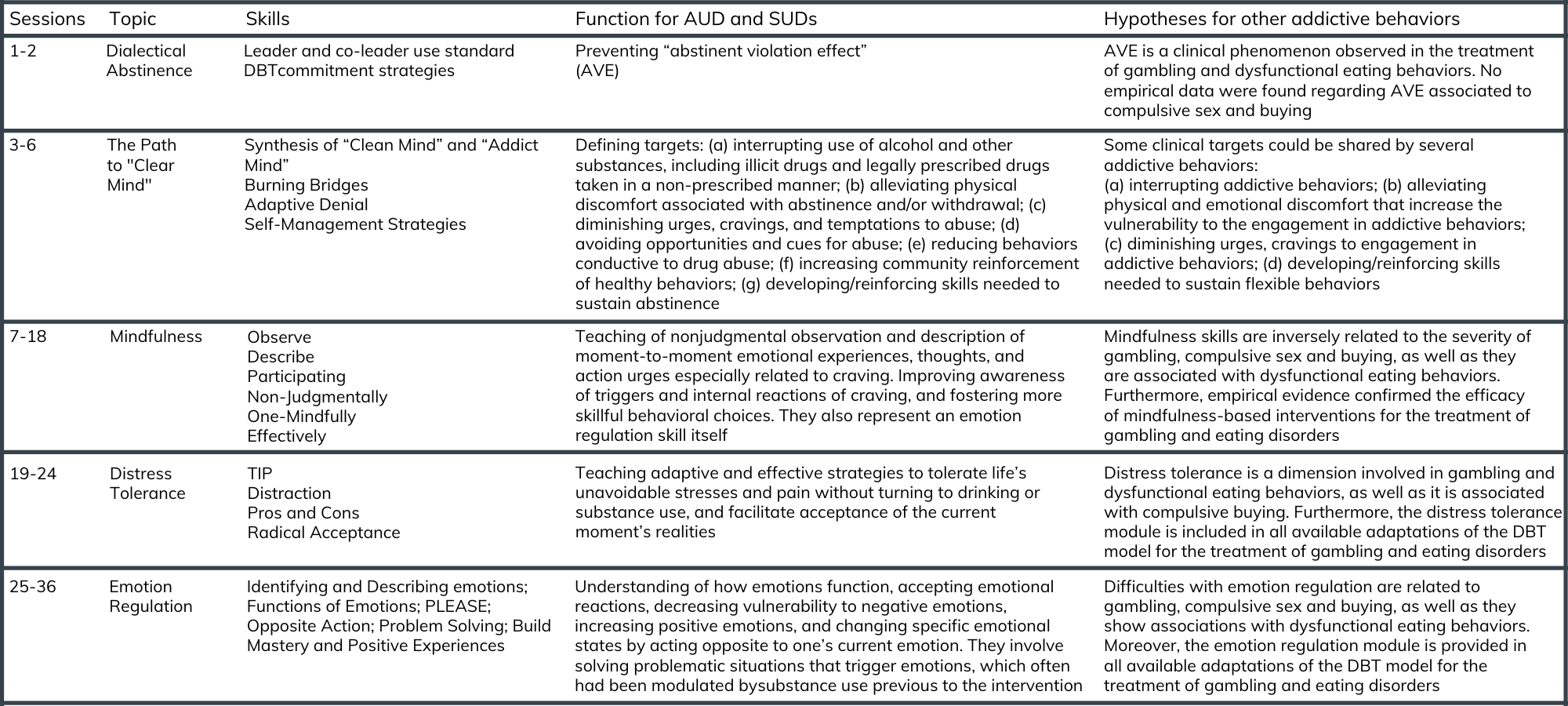

This was a secondary analysis of data from an uncontrolled clinical trial (i.e., it had no comparison group) of dialectical behavior therapy for alcohol use disorder conducted with 186 individuals recruited from a hospital-based alcohol and other drug detoxification unit in Milan, Italy. Immediately following discharge from the detoxification unit, all participants received a condensed, 3-month version of the dialectical behavior therapy skills training program developed for the treatment of alcohol use disorder and concurrent substance use disorders (the full dialectical behavior therapy skills training protocol usually takes ~6 months to complete). Treatment was provided on an outpatient basis and had two phases: 1) an intensive phase that consisted of five sessions a week for the first month, and 2) a post-intensive phase with two sessions a week for the subsequent two months. Each session was three hours long; the total number of sessions was 36.

Dialectical behavior therapy skills designed to specifically target substance use problems were incorporated in the treatment, including behavior chain analyses when participants engaged in ineffective behaviors (e.g., alcohol or substance use, gambling and binge or restrictive eating) or failed to engage in effective behaviors (e.g., they exhibited difficulties in skills use). Consistently with other DBT for substance use disorder programs, the intervention did not present interpersonal effectiveness skills because the goal is to present the most relevant skills for addressing substances in a relatively short period.

Notably, the treatment did not involve complementary individual therapy as is typical in dialectical behavior therapy, or the use of diary cards, which are used by individuals receiving classic dialectical behavior therapy to help them keep track of their emotions and behaviors during treatment. However, as is typical in dialectical behavior therapy, participants were assigned homework with worksheets in each group session and asked to complete and bring these to subsequent sessions for check-in.

Study measures included, 1) the Addiction Severity Index, 2) the Shorter PROMIS Questionnaire, a self-report instrument for simultaneous assessment of 16 addictive behaviors including, use of alcohol, tobacco, illegal drugs, prescription drugs, gambling, sex, dominant and submissive relationships, shopping, food binging, restriction, caffeine, work, exercise, and compulsive helping, 3) the Difficulties In Emotion Regulation Scale, and 4) the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II, a self-report scale assessing psychological flexibility and emotional avoidance behaviors (referred to in this paper as experiential avoidance).

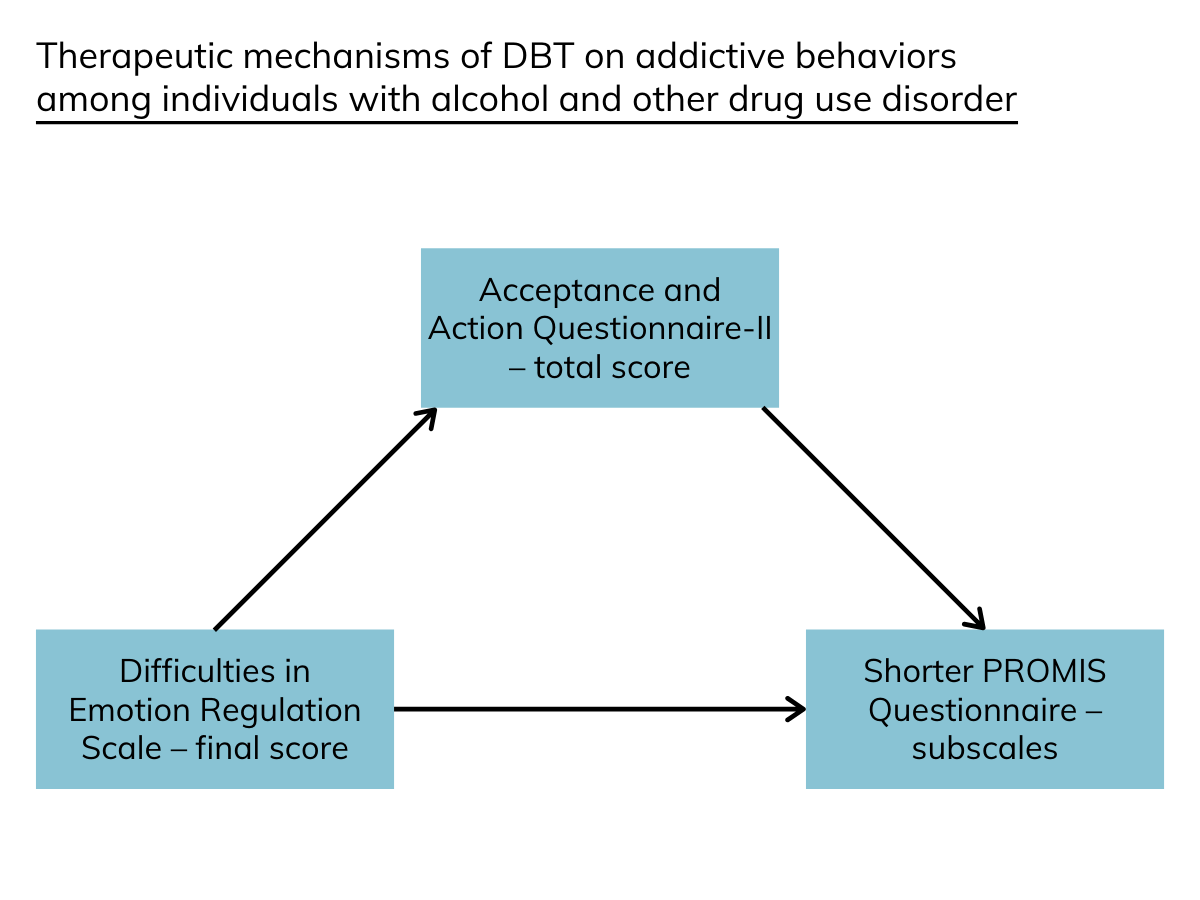

The authors explored within-participant change in these measures from beginning to end of dialectical behavior therapy treatment using paired t-tests. They also explored the potential reasons for the changes by testing for mediation – causal chains in which one variable affects a second variable that, in turn, affects a third variable (an example would be exposure to a therapy leading to an increase in coping skills, which in turn leads to reductions in alcohol use).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

From pre- to post-treatment, the authors observed a small effect size improvements in gambling (d= –0.26), compulsive sexual behavior (d= –0.32), compulsive spending (d= –0.32), binge eating (d= –0.30), and restrictive eating (d= –0.27). Also, a large effect size improvement was seen in emotion regulation (d= –1.17), and a medium effect size improvement was observed in emotional avoidance (d= –0.71).

Figure 2. Description of the DBT program and it’s uses for alcohol and other drug use disorder.

Additionally, pre- to post-treatment improvements in difficulties with emotion regulation predicted statistically significant but relatively small effect size decreases in gambling (R2= .08), sex (R2= .05), shopping (R2= .14), food binging (R2= .12) and food restriction (R2= .08). In other words, while these changes may be statistically reliable (the chances of the observed effect being a result of random chance are less than 5%), their association with real-world change may be modest.

Figure 3.

They also found that improvements in emotional avoidance (i.e., they became more willing and able to face difficult feelings) explained the relationship between difficulties with emotion regulation and food binging, food restriction, and shopping. In other words, being more able to face and address feelings subsequent to baseline levels of emotion dysregulation, largely drove reductions in food binging and restriction behaviors, and shopping. Additionally, reductions in emotional avoidance partially explained the relationship between difficulties with emotion regulation and compulsive shopping, meaning facing difficult feelings partially accounted for reductions in this behavior. There were however no mediation effects for gambling, or compulsive sexual behavior.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Dialectical behavior therapy is a well-established first-line treatment for borderline personality disorder that has also demonstrated some promise for the treatment of addiction. Because dialectical behavior therapy teaches individuals a broad array of skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, the authors of this paper hypothesized its benefits may generalize to problem behaviors that aren’t necessarily the main target of alcohol use disorder treatment, such as gambling problems, compulsive shopping and sexual behaviors, and restrictive and binge eating.

Using a modified dialectical behavior therapy skills treatment, the authors observed statistically significant, though fairly modest, decreases in gambling and compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive shopping, and binge and restrictive eating from pre- to post-treatment. With respect to gambling and dysfunctional eating behaviors, these findings are in line with emerging literatures speaking to the potential of dialectical behavior therapy adaption for the treatment of gambling problems and restrictive and binge eating disorders.

However, findings from this study do not constitute evidence of the benefits of DBT for alcohol use disorder or for these co-occurring behavioral problems among individuals with AUD since this was a single group trial without a comparison group. More rigorous comparative trials are needed before we can have confidence that DBT is at least on par with other treatments for these conditions, or actually superior.

The analyses also showed that pre- to post-treatment improvements in addictive behaviors were positively linked to changes in difficulties with emotion regulation. This evidence is consistent with dialectical behavior therapy principles that assume that engagement in maladaptive or dysfunctional behaviors is often driven by problems regulating emotions.

Considering the authors’ exploration of causal chains (i.e., mediation effects), their analyses found significant effects of pre- to post-treatment changes of emotional avoidance on the relationships between improvements in difficulties with emotion regulation and the decrease of severity of compulsive shopping and dysfunctional eating behaviors. This improvement might be linked to the learning and practice of dialectical behavior therapy behavioral and cognitive skills, as demonstrated in the treatment of substance-related behaviors. At the same time, there were no mediation effects for gambling, and compulsive sexual and shopping behaviors, which undercuts this hypothesis. It is possible that other, unmeasured factors were driving this change in this study, or as the authors note, gambling, and compulsive sexual and shopping behaviors might have different precursors to compulsive shopping and binge and restricting eating behaviors, and therefore respond differently to DBT skills training.

Dialectical behavior therapy is part of what is known as the third wave of psychological treatments, following behavioral therapies (1st wave) and cognitive behavioral therapy (2nd wave). Other third-wave therapies include acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Though none of these third-wave treatments were originally developed to address addiction, they are increasingly being used in their treatment or adapted for the treatment of substance use disorder. For instance, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy was adapted into mindfulness-based relapse prevention. While there are not data to suggest these treatments are better than existing first line treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy, evidence exists suggesting they may be as effective, and they can also address specific areas of need (e.g., shame, emotion dysregulation) and can be important parts of comprehensive treatment and recovery plans.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study did not include a control or comparison group, so it can’t be known if observed outcomes are a result of the dialectical behavior therapy treatment or some other unmeasured factor such as general improvements across time.

- The interpersonal effectiveness module of classic dialectical behavior therapy was excluded. Given individuals with substance use disorders often have interpersonal and assertiveness skills deficits, this set of skills would likely be beneficial to individuals with substance use disorder.

- Only a small portion of participants with alcohol use disorder met diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder or eating disorders, which reduces confidence in the reliability of the estimates of the effects in those sub-groups.

- The absence of follow-up evaluations after the end of treatment is an additional limitation of the study. No conclusions can be drawn on the effects of dialectical behavior therapy following treatment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Dialectical behavior therapy is a skills-based treatment that is increasingly being employed for the treatment of substance use disorders. Because DBT teaches individuals a broad array of skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, the authors of this paper hypothesized its benefits may generalize to problem behaviors that aren’t necessarily the main target of alcohol use disorder treatment but may be driven by many of these same underlying mechanisms. They observed statistically significant, though small effect size reductions in gambling and compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive shopping, and binge and restrictive eating from pre- to post-treatment. Further, improvements in compulsive shopping and binge and restrictive eating were related to reductions in emotional avoidance. DBT is part of a suite of newer cognitive behavioral treatments, along with acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, that when tested for the treatment of addiction, generally do as well as cognitive behavioral therapy, and may be particularly helpful for addressing specific vulnerabilities including problems regulating emotions and accepting situations/circumstances that can’t be changed. These promising clinical approaches bear consideration when exploring treatment options for substance use disorders.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Dialectical behavior therapy is a skills-based treatment that is increasingly being employed for the treatment of substance use disorders. Because DBT teaches individuals a broad array of skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, the authors of this paper hypothesized its benefits may generalize to problem behaviors that aren’t necessarily the main target of alcohol use disorder treatment. They observed statistically significant, though small effect size reductions in gambling and compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive shopping, and binge and restrictive eating from pre- to post-treatment. Further, improvements in compulsive shopping and binge and restrictive eating were related to reductions in emotional avoidance. DBT is part of a suite of newer cognitive behavioral treatments, along with acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, that when tested for the treatment of addiction, generally do as well as cognitive behavioral therapy, and may be particularly helpful for addressing specific vulnerabilities including problems regulating emotions and accepting situations/circumstances that can’t be changed. These promising clinical approaches have potential utility in the treatment options for substance use disorders.

- For scientists: Dialectical behavior therapy is a skills-based treatment that is increasingly being employed for the treatment of substance use disorders. Because DBT teaches individuals a broad array of skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, the authors of this paper hypothesized DBT may have transdiagnostic benefits that generalize to problem behaviors that aren’t necessarily the main target of alcohol use disorder treatment. They observed statistically significant, though small effect size reductions in gambling and compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive shopping, and binge and restrictive eating from pre- to post-treatment. Further, improvements in compulsive shopping and binge and restrictive eating were related to reductions in emotional avoidance. Dialectical behavior therapy is part of a suite of newer cognitive behavioral treatments, along with acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, that when tested for the treatment of addiction, generally do as well as cognitive behavioral therapy, and may be particularly helpful for addressing specific vulnerabilities including problems regulating emotions and accepting situations/circumstances that can’t be changed. More research is needed comparing third-wave treatments for substance use disorder to current first line treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and explore ancillary effects of these interventions on co-occurring psychological conditions. It may be that DBT works well for certain sub-groups of patients, such as those with intense emotion regulation difficulties, but more research is needed to confirm such treatment matching hypotheses.

- For policy makers: Dialectical behavior therapy is a skills-based treatment that is increasingly being employed for the treatment of substance use disorders. Because dialectical behavior therapy teaches individuals a broad array of skills for emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness, the authors of this paper hypothesized its benefits may generalize to problem behaviors that aren’t necessarily the main target of alcohol use disorder treatment. The researchers observed statistically significant, though small, effect size reductions in gambling and compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive shopping, and binge and restrictive eating from pre- to post-treatment. Further, improvements in compulsive shopping and binge and restrictive eating were related to reductions in emotional avoidance. DBT is part of a suite of newer cognitive behavioral treatments, along with acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, that when tested for the treatment of addiction, generally do as well as cognitive behavioral therapy, and may be particularly helpful for addressing specific vulnerabilities including problems regulating emotions and accepting situations/circumstances that can’t be changed. Although it seems unlikely that DBT will outperform existing treatment approaches, it could nevertheless engage more people in treatment as it may attract certain individuals interested in its novel focus that incorporates new ideas about emotion regulation and mindfulness.

CITATIONS

Cavicchioli, M., Rammela, P., Vassena, G., Simone, G., Prudenziati, F., Sirtori, F., . . . Maffei, C. (2020). Dialectical behaviour therapy skills training for the treatment of addictive behaviours among individuals with alcohol use disorder: The effect of emotion regulation and experiential avoidance. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 46(3), 1-17. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2020.1712411