Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT): Preliminary Evaluation of Effectiveness

The term “third-wave” is intended to distinguish these approaches from the more traditional forms of “second-wave” behavioral therapy, often simply called cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which focuses on understanding and challenging maladaptive thinking patterns.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

One group of novel treatments that have been applied to the treatment of SUDs are called “third-wave” (also known as “contextual”) behavioral treatments, including Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP, which has been reviewed in a prior RRI newsletter; see here), and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Although each use a different set of techniques and exercises, they have in common an emphasis on disconnecting from the influence of thinking on behavior.

The “first wave” of behavioral treatments were based almost entirely on pioneering behavioral theories such as classical conditioning and operant conditioning. It is important to note that some researchers believe that these newer treatments remain under the larger CBT umbrella and do not constitute a “new wave” of treatments. Although this discussion is beyond this research summary, this review highlights the similarities and differences between these more recently developed treatments and traditional CBT (see here).

When new treatments are developed, and alleged to help individuals with substance use disorders, it is important to investigate:

- a) whether they are effective

- b) whether they are effective compared to existing treatments

Such research will help determine whether it is worth the extra resources that it might take to implement this new treatment in substance use disorder (SUD) programs and clinics.

While there has been much research studying the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD), research on these newer approaches have only recently been conducted for individuals with SUD, and comparatively less is known about whether these treatments can help.

This study by Lee and colleagues presents the results of a meta-analysis (an analysis of several studies at the same time) on the small, but growing body of research on Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

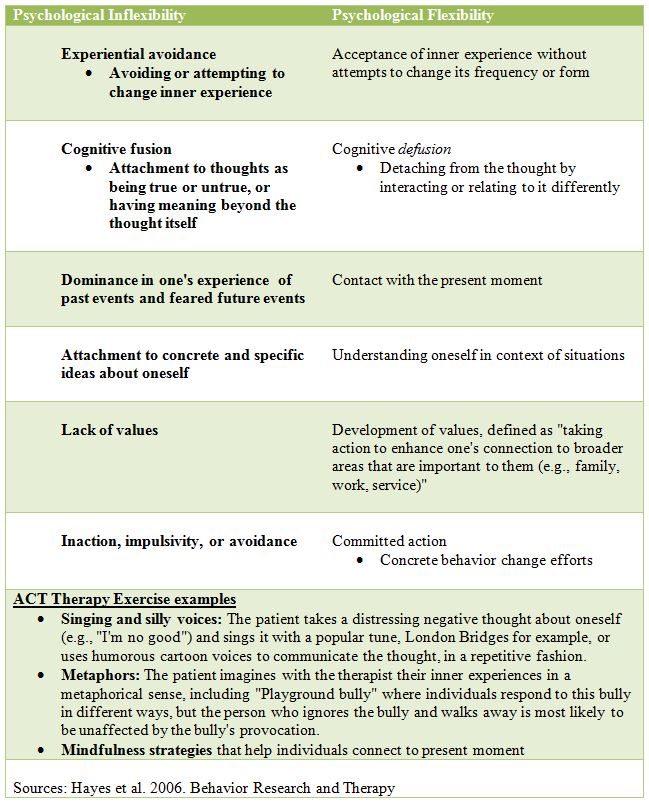

Lee and his co-authors conducted a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD). We will very briefly summarize the goals and processes in ACT. Unlike behavioral approaches that attempt to modify the forms of inner experience (e.g., constructing more “balanced” thoughts), the goal of ACT is to transition from psychological inflexibility to psychological flexibility, defined by ACT researchers, clinicians, and theorists as the “process of contacting the present moment fully as a conscious human being and persisting or changing behavior in the service of chosen values”. It is worth highlighting that self-report questionnaires assessing psychological flexibility defined in this way have been shown to be associated with quality of life, for example.

Note: ACT targets are not symptoms, such as substance use, but rather these six core processes, which are theorized to result in values-based action that is inconsistent with behaviors that impair functioning and well-being, thus indirectly reducing substance use.

To be included in the meta-analysis, the study of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) had to be a randomized controlled trial with a comparison to at least one other active treatment (i.e., no-treatment comparison conditions were not included) and measure substance use outcomes among individuals that had substance use disorder (SUD). In this paper, SUD included nicotine although traditional definitions separate nicotine from alcohol and other drugs.

The meta-analysis included 1386 participants; 58% were female and 85% White, and the mean age was 40 years old. Five studies focused on cigarette smoking, one on amphetatmines, two on opioid use, and two polydrug use; this summary focuses on the drug studies, in particular.

For the analysis of “follow-up” assessments, the last assessment completed was used, which ranged from 2 to 18 months. Drop-out rates between the ACT condition and comparison group were similar (about 33% and 34%, respectively, across all 10 studies).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The meta-analysis of all 10 studies showed that Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) had a small benefit after the treatment and a medium benefit at follow-up. In terms of the actual ACT advantage, extrapolated from the statistics provided in the paper, approximately 61% of the ACT group were above the average outcomes for comparison groups after treatment delivery and 67% at the follow-up.

When examining only the five studies that focused on drug use disorders, the post-treatment effect was similar; however, authors did not report a comparison of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) to other treatments for individuals with drug use disorders at follow-up. Given the small number of studies, below we examine these five individual studies used in the meta-analysis in more detail.

Although the study is presented as a comparison of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) to other approaches, in the most exemplary study, Luoma and colleagues examined whether adding ACT (designed specifically to target feelings of shame) to residential SUD treatment-as-usual (TAU) for 68 individuals produced better outcomes than TAU (without ACT) for 65 individuals (see here). The residential program lasted roughly 28 days, and included group sessions on relapse prevention, life skills, and anger management for six days per week, as well as 2 hours of individual therapy per week which often focused on 12-step facilitation. Individuals randomized to receive ACT attended three groups, for 2 hours each, in full one week, instead of 6 hours of the TAU residential programming.

Results showed patients receiving Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) were 2 times more likely to be abstinent in a given week across 4 month follow-up after treatment discharge, and more likely to engage in continuing care treatment. Interestingly, they had slower reductions in shame than TAU during treatment, while less shame during treatment predicted more substance use after treatment and more shame during treatment predicted more continuing care attendance.

In other words, more shame measured at the end of treatment was associated with better outcomes during the follow-up. Authors suggested that Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) may have facilitated patients’ fully experiencing and accepting shame, leading to greater motivation to engage in healthy behaviors and use recovery supports after treatment. As such, in this study, ACT may have enhanced traditional 12-step-based treatments through mindfulness and acceptance exercises.

Also, closer examinations of the four other studies in this meta-analysis for individuals with drug use disorders show that Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) and an intensive 12-step facilitation had similar effects on outcomes of methadone-maintenance treatment seeking individuals with opioid use disorder (see here), and that ACT led to greater likelihood of successful extended methadone detoxification for patients with opioid use disorder (but similar rates of opioid use; see here).

As a stand-alone treatment, Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) led to better 18-month abstinence rates than cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in a small sample of female prisoners in Spain (see here), and had similar benefit compared to CBT for individuals with amphetamine use disorders (see here),

To this point, Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) studies have focused on specialized populations such as female prisoners in Spain and individuals in methadone maintenance or long-term detoxification. The Luoma et al. study suggests ACT may have promise as a tool to enhance existing substance use disorder (SUD) interventions, but this research is still in very early stages.

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

As research is conducted on a new treatment intended to help individuals with substance use disorder (SUD), a meta-analysis can provide a summary of this research – using statistics rather than conveying a general sense of the findings – often across a range of settings and samples.

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) may be a helpful approach for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD), and none of the studies included in the meta-analysis for those with drug use disorder suggested ACT is harmful. More research is needed, however, before broader implications for the treatment and recovery field can be offered.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This meta-analysis was limited because it was conducted on a small number of studies. As authors suggest, their findings should be considered preliminary.

- Also, there are no randomized controlled trials of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) for individuals with alcohol use disorder, marijuana use disorder, or cocaine use disorder specifically, though the Luoma et al. study examined patients in residential treatment; it is likely some of these patients met criteria for these disorders, though specific substance use disorder (SUD) was not assessed as part of the study.

NEXT STEPS

Trials of Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) for individuals with addiction appear to be ongoing. Next steps involve studies on whether and how ACT is helpful for individuals with a range of addictions, and in a range of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment settings.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: If Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) -based mindfulness and acceptance strategies are engaging, this review suggests they are unlikely to do harm, and may help.

- For scientists: Although meta-analyses have many advantages, in the non-nicotine studies, ACT was delivered in a variety of ways (e.g., compared as a stand-alone treatment to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) among female prisoners vs. as an adjunct to an intensive residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment program). Also, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the usefulness of ACT for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) with a meta-analysis until more studies can be included. ACT appears to hold promise as a treatment for individuals with addiction and certainly warrants rigorous investigation.

- For policy makers: Given the promise shown by Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT), consider funding studies that evaluate its efficacy in enhancing treatment and recovery outcomes for individuals with substance use disorder (SUD).

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: If you find your patients are engaged by ACT-based mindfulness and acceptance strategies, this review suggests they are unlikely to do harm and may improve outcomes. ACT theory suggests it could help by facilitating patients’ full experience of painful emotions that motivate ongoing engagement in care.

CITATIONS

Lee, E. B., An, W., Levin, M. E., & Twohig, M. P. (2015). An initial meta-analysis of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for treating substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend, 155, 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.004