Does providing feedback to therapists about their rapport with patients improve patient drinking outcomes?

A large body of research across numerous psychiatric conditions has shown that therapeutic alliance – the positive regard and cohesion between patient and therapist – is associated with better treatment outcomes. This study investigated whether alcohol use disorder treatment outcomes can be improved by providing therapists with information about patients’ perceptions of alliance, offering them an opportunity to improve the alliance, and thereby potentially improving outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Therapeutic alliance—the emotional bond and shared beliefs in the tasks and goals of treatment shared by therapist and patient—has been identified as an important mechanism of change, explaining improved outcomes across psychotherapeutic approaches. In the context of substance use disorder treatment, therapeutic alliance, especially when rated by patients early in treatment, is a consistent predictor of future treatment engagement, early improvements in treatment, and more positive post-treatment outcomes. It is assumed that therapeutic alliance mediates these outcomes, or said another way, therapeutic alliance is a causal link between the therapist’s actions and patient outcomes. It has also been suggested that providing therapists with feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance could provide an additional boost to treatment outcomes by helping providers make adjustments when the alliance is weak or waning.

Research to date, however, has been structured in such a way that we can’t know conclusively whether therapeutic alliance actually causes these better addiction treatment outcomes. This is because existing research on this topic has usually involved taking one or two measurements of therapeutic alliance during treatment (typically earlier) and testing associations between alliance and outcomes post-treatment and/or during follow-up. These kinds of research designs, though instructive, do not yield the type of data needed to provide causal evidence. Rather, to evaluate this, multiple assessments of both therapeutic alliance during treatment and alcohol use during and following treatment are needed. Further, the effects of providing therapists with feedback on patient perceptions of therapeutic alliance have not been explored in the context of an alcohol use disorder clinical trial.

The authors therefore sought to test whether providing feedback to therapists about their patients’ perception of therapeutic alliance in the context of alcohol use disorder treatment would lead to improvements in therapeutic alliance, and subsequently better patient drinking outcomes.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a randomized controlled trial with 155 participants receiving 12, weekly sessions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for alcohol use disorder to determine whether feedback improved therapeutic alliance and drinking outcomes during treatment, as well as over three-, six-, nine-, and 12-month follow-up. Typically in randomized controlled trials participants are randomized to a treatment condition, however, in this study all participants received the same treatment, and provided ratings of therapeutic alliance after each therapy session, while the six study therapists were randomized to either receive these ratings as feedback (feedback condition; patient n= 51), or not to receive such ratings (no feedback condition; patient n= 104).

All participants received 12 weekly sessions of standard Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for alcohol dependence, based on the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) through the research site’s outpatient clinical program. The 12-item California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (CALPAS) was used to obtain participants’ perception of the alliance immediately following each weekly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy session. Participants were aware that therapists might be given feedback on the alliance ratings they provided. Additionally, participants were asked to report their daily alcohol consumption since their last session. Participants’ alcohol consumption was also measured using self-report over the course of one year following treatment completion. Drinking data were converted into two primary outcomes of percent days abstinent, and percent heavy drinking days (defined as 4+/5+ drinks per day for women/men).

The study was divided into three phases. In Phase 1, none of the therapists received feedback, and in Phases 2 and 3, whether therapists received feedback was based on random assignment. Therapists were blind to the study hypotheses, trained on the study protocol, and supervised weekly, including reviews of audiotaped sessions to ensure compliance to the treatment manual.

For therapists in the feedback condition, feedback about therapeutic alliance was provided in weekly, in-person supervision sessions that also addressed clinical concerns and adherence to the cognitive behavioral therapy framework. Therapists in the feedback condition were encouraged to use suggestions on the feedback report. Furthermore, therapists were asked not to discuss alliance feedback scores with patients (unless brought up by the patient).

For therapists in the no feedback condition, supervision focused only on clinical concerns and adherence to the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy framework. Therapeutic alliance was not the focus of discussion unless a therapist expressed specific concerns about the alliance.

- Participant Criteria

-

Participants were people seeking outpatient treatment for alcohol use disorder. Study inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) being 18 and 65 years of age, 2) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for a diagnosis of current alcohol dependence, 3) living within commuting distance of the program site, and 4) basic reading skills. Exclusion criteria included: 1) currently having a psychotic disorder, 2) significant neurocognitive problems, or 3) receiving alcohol or other drug treatment in the past 12 months, excluding mutual-help groups. Other psychiatric disorders were not exclusionary, but those with a concurrent drug use disorder were only included in the study if they had a primary alcohol dependence disorder.

For their analysis, the authors used a statistical approach that allowed them to control for grouping effects in data (e.g., participants who all saw the same therapist). They examined changes in both therapeutic alliance and alcohol use during treatment and post-treatment, as well as their associations. Alcohol use was reported as percentage of days abstinent or percentage of days heavy drinking between each session and over three-, six-, nine-, and 12-month follow-up.

Due to their interest in the effects of therapeutic alliance feedback on overall therapeutic alliance scores and drinking outcomes, the authors only included data from participants who attended at least two sessions in their final analysis. The overall mean number of sessions attended was 9.8, and the mean number of days between sessions was 8.5. Patients with therapists in the feedback and no feedback conditions attended a similar number of sessions and had a similar number of days between sessions.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

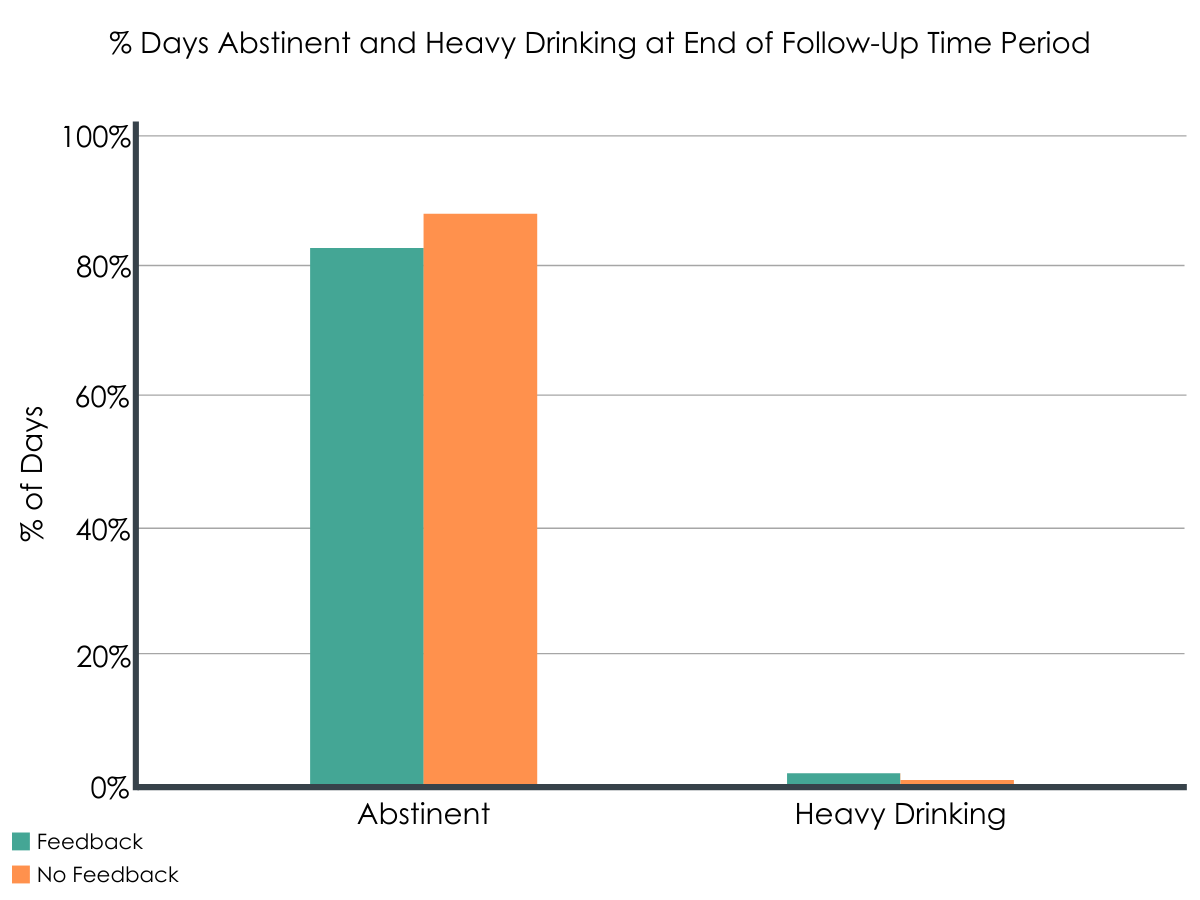

Figure 1.

Therapists found the feedback to be helpful.

Therapists in the feedback condition endorsed finding the feedback valuable, indicating that they reviewed and considered the feedback provided in all cases. Further, in 93% of cases therapists perceptions of therapeutic alliance were consistent with the participant’s, and therapists rated the feedback as “considerably” or “very helpful” in their treatment of over 88% of cases. Also, therapists reported that they applied the feedback to a “considerable” or “great extent” in treatment of over 96% of their cases.

Therapeutic alliance increased through treatment, but didn’t differ between feedback conditions.

As might be expected, on average therapeutic alliance increased over the course of treatment. However, increases in therapeutic alliance did not differ by feedback condition, indicating providing therapists with feedback did not differentially improve therapeutic alliance.

Alcohol use reduced during treatment but largely didn’t differ between feedback conditions.

As anticipated, in general, there was a significant increase in percentage of days abstinent and decrease in percentage of days heavy drinking during treatment with such increases for percentage of days abstinent and decreases for percentage of days heavy drinking slowing toward the end of treatment.

Results showed no differences in alcohol use, however, between the feedback and no feedback conditions at the end of treatment (i.e., therapy session 12). Generally this was also true for drinking measures during treatment, with the exception of session seven (approximating the halfway point in treatment), in which contrary to the authors’ hypotheses, the no feedback condition had a higher percentage of days abstinent when compared to those in the feedback condition.

Therapeutic alliance in general did however predict within-treatment alcohol use outcomes.

Results indicated that the higher the therapeutic alliance scores were at the end of the previous session (relative to a person’s own mean), the higher the percentage of days abstinent and lower percent of heavy drinking days during the interval until the next session. Therapeutic alliance was also related to alcohol use at the end of treatment, such that the higher a participant’s overall mean alliance score, the higher the percentage of days abstinent and lower percentage of heavy drinking days they reported at the end of treatment.

Alcohol use increased over follow-up but was not associated with therapeutic alliance, nor did it differ by feedback condition.

Overall, results indicated a small but statistically significant* decline in percentage of days abstinent and a small but statistically significant increase in percentage of days heavy drinking over the course of the 12-month follow-up period, meaning participants’ drinking got slightly worse during the one-year post-treatment. This dip in drinking outcomes over time was similar for the feedback and no feedback groups. Further, therapeutic alliance ratings during treatment were not associated with change in percentage of days abstinent or percentage of days heavy drinking over follow-up.

*Statistical significance indicates that the chance of this finding being a result of chance is less than 5%. In other words, we can have a high degree of confidence this finding reflects a true effect.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found evidence suggesting a potential causal relationship in general between therapeutic alliance and within-treatment reduction in alcohol use among individuals receiving a 12-week course of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for alcohol use disorder, but that providing feedback to therapists about their patients’ rating of the therapeutic alliance did not differentially affect their patients’ subsequent therapeutic alliance or their during-treatment alcohol use outcomes. Furthermore, the authors did not find evidence that therapeutic alliance influenced alcohol use over 12-month follow-up.

Though the study design allowed the authors to test the effects of patients’ ratings of their therapeutic alliance with their therapist on alcohol use outcomes, it remains possible that other factors were influencing these findings. For instance, patients’ intrinsic motivation for treatment for alcohol use disorder has been found to influence the relationship between therapeutic alliance and alcohol changes. In other words, if a patient is highly motivated to change their alcohol use, the therapeutic alliance is generally perceived as very positive, because patients are very willing to do whatever the therapist suggests; but if they are resistant to change and treatment (e.g., they are in treatment because of an employer requirement of spousal mandate), patients are more oppositional and therapeutic alliance is rated as lower, all other things being equal. Also, previous work has shown therapeutic alliance may actually benefit patients by helping them build self-efficacy. Further, alliance in other recovery-related relationships is likely to confer benefit. These factors were beyond the scope of this study and were not explored.

Results of this study did not support the authors hypothesis that providing therapists with feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance would improve alcohol use outcomes, either during treatment, or over follow-up. As the authors noted, though, this study did not include procedures that could be used to assess what therapists actually did in response to the alliance feedback that they received following each session. In this regard, although therapists assigned to receive feedback got supervision on how to improve the therapeutic alliance, and the therapist survey data suggested that therapists valued the alliance feedback and reported that they incorporated it in their work with clients, there may have been considerable variability among the therapists in the degree and manner in which this happened.

Additionally, most patients reported high levels of therapeutic alliance with little room for improvement on the scale measuring alliance (known as a ‘ceiling effect’), which could have made it more difficult to identify any potential benefit for feedback group patients. Finally, it is unclear how treatment drop out may have affected results, or if number of sessions attended was associated with therapeutic alliance. For example, it may be that individuals who dropped out of treatment early did so because they were feeling low therapeutic alliance.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Therapists were randomized to study condition, but for randomization to work, typically at least a sample size of 60 is required (for a two-group study). Only six therapists were included in this study and were randomized to conditions. Given this very small number, it is highly likely that therapists across the two conditions under investigation (feedback vs no feedback) could have differed on other important dimensions (e.g., degree of empathic skills) that could have influenced the outcomes beyond whether they received feedback or not about their patients’ ratings of therapeutic alliance.

- Four of the six therapists in the study started in the no feedback condition, and ended up in the feedback condition, which may have inadvertently unblinded therapists to the goals of the research.

- Within treatment and follow-up alcohol use was not verified using laboratory methods.

- No objective measure of therapeutic alliance was used, such as a rater reviewing therapy session tapes.

- What therapists actually did in response to the alliance feedback that they received following each session was not measured.

- Patient motivation and therapeutic alliance can interact in complex ways, and patients’ intrinsic motivation was not controlled for.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: It was found that better therapeutic alliance led to better within-treatment alcohol use outcomes, in general. Therapeutic alliance, however, was not associated with alcohol use over 12-month follow-up, nor did giving therapists feedback about their patients’ perceptions of the therapeutic alliance differentially effect alcohol use outcomes within treatment or over follow-up. Additionally, therapists receiving feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance did not lead to improvements in therapeutic alliance. This suggests that providing therapists with feedback about their patients’ perceptions of being on the same page as their therapist so that the therapist can constructively alter their in-session behavior, doesn’t seem to positively affect patients’ subsequent therapeutic alliance, or alcohol use outcomes. Yet, therapeutic alliance in general is a good thing. Thus, to the extent possible, finding a therapist who feels like a good fit may improve treatment retention and ultimately alcohol use outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: It was found that greater therapeutic alliance led to better within-treatment alcohol use outcomes, although it’s possible other factors not assessed such as patient motivation could have influenced these results. Therapeutic alliance, however, was not associated with alcohol use over 12-month follow-up, nor did therapist feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance effect alcohol use outcomes within treatment or over follow-up. Additionally, therapists receiving feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance did not lead to improvements in therapeutic alliance. This suggests that providing therapists with feedback about their patients’ perceptions of being on the same page as their therapist so that the therapist can constructively alter their in-session behavior, doesn’t seem to positively affect patients’ subsequent therapeutic alliance, or alcohol use outcomes. Yet, therapeutic alliance in general is a good thing. Thus, to the extent possible, helping connect patients with a therapist who feels like a good fit may improve treatment retention and ultimately alcohol use outcomes.

- For scientists: It was found that greater therapeutic alliance led to better within-treatment alcohol use outcomes, although it’s possible other factors not assessed such as patient motivation could have influenced these results. Therapeutic alliance, however, was not associated with alcohol use over 12-month follow-up, nor did therapist feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance effect alcohol use outcomes within treatment or over follow-up. Additionally, therapists receiving feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance did not lead to improvements in therapeutic alliance. Ultimately, how therapists used the feedback in this study was at their discretion. Future research might consider development of specific guidelines derived from a database of clinical cases that consists of patterns of feedback over the course of therapy and associated therapeutic action that followed from them.

- For policy makers: It was found that greater therapeutic alliance led to better within-treatment alcohol use outcomes, although it’s possible other factors not assessed such as patient motivation could have influenced these results. Therapeutic alliance, however, was not associated with alcohol use over 12-month follow-up, nor did therapist feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance effect alcohol use outcomes within treatment or over follow-up. Additionally, therapists receiving feedback about patients’ perceptions of therapeutic alliance did not lead to improvements in therapeutic alliance. Though therapeutic alliance did not affect long-term alcohol use outcomes in this study, cultivating therapeutic alliance will always be an important component of any therapy, and likely gives rise to numerous benefits not investigated in this study. Treatment outcomes may be improved by incentivizing treatment programs to improve therapeutic alliance.

CITATIONS

Maisto, S. A., Schlauch, R. C., Connors, G. J., Dearing, R. L., & O’Hern, K. A. (2020). Effects of therapist feedback on the therapeutic alliance and alcohol use outcomes in the outpatient treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(4), 960-972. doi: 10.1111/acer.14297