Paying providers for good outcomes is better in theory than practice

Many healthcare systems are shifting from a fee-for-service payment model, where providers are paid based on the quantity of services provided, to a value-based payment model, which incentivizes quality and cost-efficiency. This study evaluated the impact of implementing one of these value-based payment models, “pay-for-performance”, in England’s treatment system, with providers paid based on outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Given the high and increasing costs of medical care in developed nations, many healthcare systems and health insurers have begun shifting from fee-for-service payment models, where providers are paid based on the volume of services provided, to value-based payment models, where providers are rewarded for high-quality and cost-efficient care. Some value-based payment models include accountable care organizations, bundled payment, and pay-for-performance schemes. Pay-for- performance schemes are reimbursement models where payment to the provider’s organization is linked to 1 or more quality measures. These quality measures might include process measures that reflect what a provider does to maintain or improve a patient’s health (e.g., initiating a patient with an opioid use disorder on medication treatment) or outcome measures that reflect the impact of the provider’s care on the health status of a patient (e.g., hospital readmission rate of a patient being treated for an opioid use disorder).

Implementing value-based payment models in the substance use disorder treatment system is especially attractive because the treatment system could theoretically be incentivized to deliver comprehensive care across a continuum rather than in acute episodes, better aligning with chronic disease management. Accordingly, these payment models could promote greater implementation of evidence-based treatments. However, even though studies have shown that implementing value-based payment models is promising in substance use disorder treatment, findings are mixed. In 2012, several organizational areas in England piloted a pay-for-performance scheme that paid providers based on patient outcomes. Evaluation of this program revealed that patients experienced worse outcomes, including lower treatment initiation and completion along with longer waiting times. In this study, researchers wanted to examine if this scheme had unintended consequences on the wider substance use disorder population rather than only those receiving treatment. Findings could provider further insight into a new payment model that many in the field see as innovative and promising.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used administrative claims data from 2009 to 2016 to examine whether a pay-for-performance scheme implemented in some areas of England led to unintended consequences in a wider population of individuals at risk for substance-related harm by comparing hospital admissions among individuals in areas where the scheme was implemented with hospital admissions among individuals where the scheme was not implemented.

In 2012, several organizational areas in England piloted a pay-for-performance scheme that paid providers based on patient outcomes. Theoretically, policymakers believed that this new payment model would incentivize the system to improve outcomes related to sustaining a patient’s recovery. The patient outcome measures that provider reimbursement was based upon were abstinence from the presenting (i.e., “primary”) substance, completing and remaining abstinent through the duration of treatment, and treatment readmission within 12 months of completion. Evaluation of this program revealed that patients experienced worse outcomes, including lower treatment initiation and completion along with longer waiting times. The pilot was discontinued in 2014 without national adoption of the scheme, partly due to these findings. It is possible that the pilot had an impact on individuals needing treatment for substance use disorder who did not receive treatment, perhaps due to lower initiation rates and longer wait times.

The study period was defined as 2009 to 2016, which allowed for approximately 4 years of data before the pay-for-performance scheme was implemented, 2 years of data during the scheme, and 2 years of data after the scheme. The data source was the Hospital Episode Statistics, which included clinical information, patient sociodemographics, and administrative information. Researchers defined the population of interest as individuals with at least 1 drug-related hospital admission during the study period using International Classification of Disease 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. The 3 outcomes of interest were the count of total hospital admissions, emergency hospitals admissions, and hospital admissions containing a substance-related diagnosis.

To compare the hospital admission outcomes for the areas that participated in the pay-for-performance scheme and the comparison areas, the research team examined the change in each of the 3 hospital admissions outcomes from the 4 years before implementing the scheme to approximately 2 years after implementing the scheme, when the pilot program ended. They then tested whether the areas that implemented the scheme showed a different degree of change (i.e., greater increase) over time than the comparison areas. For these primary analyses, they adjusted statistically for demographic and clinical factors that predicted hospital admission outcomes to isolate, as best they could, the effect of the pay-for-performance scheme.

Three secondary analyses were conducted to potentially address some of the limitations of the primary analyses. These included restricting the comparison areas to 51 of the 141 organizational areas that were most similar to the intervention areas (i.e., matched comparison areas), restricting the defined population of interest to only those who had a qualifying admission (i.e., individuals with at least 1 drug-related hospital admission) in the intervention period, and restricting the defined population of interest to only those who had a qualifying admission (i.e., individuals with at least 1 drug-related hospital admission) in the pre-intervention period.

The parallel trends assumption, a critical feature for this type of analysis (called a Difference-Difference study design), states that although intervention and comparison areas may have different levels of the outcome of interest prior to the start of the pay-for-performance scheme, their trends in pre-treatment outcomes should be the same. In other words, there can be no evidence that hospital admissions trends were different for the hospitals that implemented the pay-for-performance scheme and the hospitals that did not before this scheme was implemented. This assumption was met for all primary analyses and nearly all secondary analyses except for the impact of the intervention on total hospital admissions when the population of interest is restricted to only qualifying admissions during the intervention period.

Eight organizational areas containing 37,964 individuals of interest participated in the pay-for-performance scheme from April 2012 to March 2014 and were purposively selected to be representative of an applicant sample of 29 areas, while 141 organizational areas containing 534,581 individuals of interest served as comparisons. The individuals in the intervention areas tended to be less racially and ethnically diverse and generally were of higher socioeconomic status compared to the non-intervention areas, although age and gender was similar. Matched comparison areas, a subset of the comparison areas that were selected based on type of substance upon admission and socioeconomic status, were more similar to intervention areas based of clinical characteristics and sociodemographic factors.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The pay-for-performance scheme was associated with an increase in total hospital admissions.

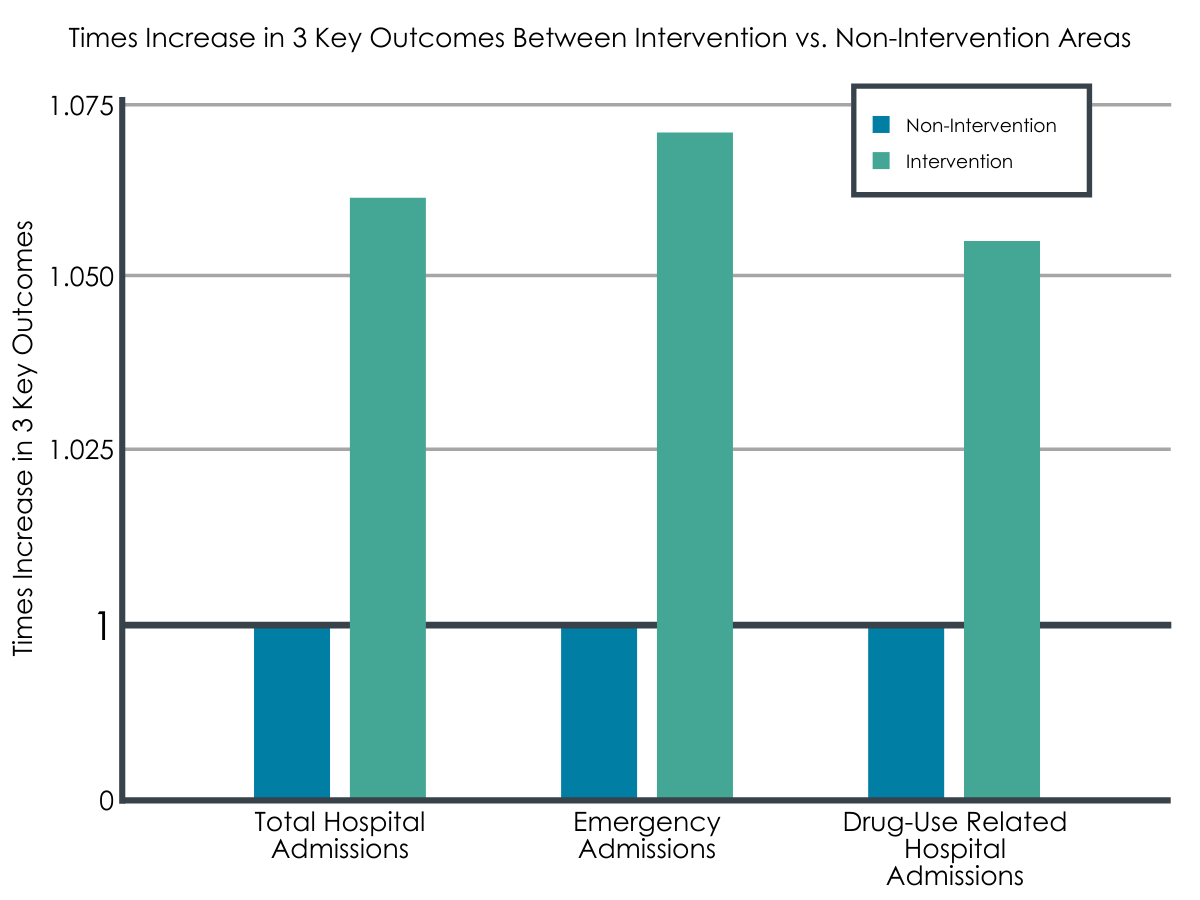

For individuals with a need for substance use disorder treatment initially residing in an intervention area, annual total hospital admissions were 1.064 times higher compared with non-intervention areas, corresponding to 0.062 annual total hospital admissions per person. Secondary analyses were similar to the primary analysis.

The pay-for-performance scheme was associated with an increase in emergency admissions.

For individuals with a need for substance use disorder treatment, based on having at least 1 drug-related hospital admission during the study period, initially residing in an intervention area, annual emergency hospital admissions were 1.073 times higher compared with non-intervention areas, corresponding to 0.045 annual emergency hospital admissions per person. Secondary analyses were similar to the primary analysis.

The pay-for-performance scheme was associated with an increase in drug use-related hospital admissions.

For individuals with a need for substance use disorder treatment initially residing in an intervention area, annual hospital admissions including a substance-related diagnosis were 1.055 times higher compared with non-intervention areas, corresponding to 0.013 annual substance-related admissions per person. Secondary analyses differed. The analysis restricting the population of interest to only those with a qualifying admission during the intervention period had higher admissions than the primary analysis whereas the analysis restricting the population of interest to only those with a qualifying admission during the pre-intervention period showed no difference between intervention and non-intervention areas.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study used a rigorous study design to show that a pay-for-performance scheme implemented in England, where providers were paid based on patient outcomes of abstinence from presenting substance, abstinent completion of treatment, and treatment readmission within 12 months of completion, likely had the unintended consequence of leading to worse outcomes for the entire population at risk for substance-related harm beyond only those seeking substance use disorder treatment.

Previous studies evaluating this pay-for-performance scheme revealed lower treatment initiation and longer wait times for intervention areas. These previous findings could explain the current findings of this study in that access to treatment was diminished in these areas, leading to unmet treatment need that may have resulted in increased hospitalizations. This scheme incentivized abstinence, which may have conflicted with the goals of patients considering treatment, resulting in them forgoing treatment. Future research should explore how alignment of patients’ goals with the pay-for-performance scheme affects outcomes.

Although the difference between the outcomes of interest may be small for a given individual, the public health implications are noteworthy. The researchers estimated that there were 3,352 additional emergency admissions in the 8 intervention areas during the intervention period, equivalent to a minimum of $2.8 million in additional hospital expenditures. In the post-intervention period, there was little difference in the hospital admissions of intervention and non-intervention areas, increasing confidence that the pay-for-performance scheme was, in fact, responsible for the poorer outcomes. If these findings were replicated after nationwide adoption of the pay-for-performance scheme, the economic and clinical burden on England would be substantial.

A previous evaluation of this pilot program also revealed significant implementation issues, such as increased administrative burden and challenges in reorienting a system to focus on abstinence, which may explain the observed detrimental patient outcomes. Beyond implementation issues, other challenges of pay-for-performance schemes include providers selecting patients that are likely to have better outcomes (also known as cherry-picking). This was minimized in this pilot program by using risk-adjusted payments and basing these payments on an assessment by an independent agency. Nevertheless, selecting patients who are likely to do better in treatment, such as individuals with less severe disorders, has been seen in other performance-based payment models in the substance use disorder field.

Even though the findings from this study may not support widespread adoption of pay-for-performance schemes in England, generalizing these findings to treatment systems in other countries should be done with caution. Pay-for-performance schemes and other value-based payment models may offer promise in a treatment system that is fragmented, oftentimes delivers care that is not evidence-based, and incentivizes acute episodes of treatment. These innovative payment models that focus on provider accountability and care coordination may incentivize a comprehensive continuum of care that aligns well with a chronic disease management treatment model. In addition, these payment models can be designed to encourage integration, incentivize early interventions at vital touchpoints, and address social determinants of health. In fact, value-based payment models are recently emerging in the United States, such as the Addiction Recovery Medical Home Alternative Payment Model and the Patient-Centered Opioid Addiction Treatment Alternative Payment Model.

Given these theoretical advantages of value-based payment models, including pay-for-performance schemes, more research is needed to better understand the implementation challenges and the most appropriate designs for these payment models. It may be that implementing pay-for-performance schemes based on process measures or a mixture of process and outcomes measures are more feasible than ones based on outcomes measures.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Generalizing study findings to other healthcare systems should be done with caution, especially to the United States where value-based payment models may be more effective in addressing a more fragmented and siloed treatment system.

- The wider population with substance use disorder was defined as individuals with at least 1 drug-related hospital admission during the study period, which represents only a subset of this population limited to those who have both utilized the healthcare system and received a substance-related diagnosis.

- Participation in the pay-for-performance scheme was not randomized. Therefore, the treatment systems in areas that elected to participate in the scheme may have been different than the comparison areas on factors not accounted for in this analysis.

- There could have been differential changes between the intervention and non-intervention sites not captured by this analysis, such as differential trends in the type or severity of substance use disorders.

- A significant number of individuals were dropped from the analysis because of missing data. If these individuals were different from those included in the analysis, this could introduce bias into the study.

BOTTOM LINE

This study examined whether a pay-for-performance scheme implemented in some areas of England led to unintended consequences in a wider population of individuals at risk for substance-related harm by comparing hospital admissions among individuals in areas where the scheme was implemented with hospital admissions among individuals where the scheme was not implemented. The study found that the pay-for-performance scheme that paid treatment providers based on patient outcomes likely had the unintended consequence of leading to worse outcomes for the entire population at risk for substance-related harm beyond only those seeking substance use disorder treatment.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study did not provide support for a pay-for-performance scheme in England, although these and other value-based payment models may offer promise in treatment systems like the United States where reimbursement of services is done by a mix of public and private entities rather than single payer system. It may be important to understand how treatment programs are reimbursed for their services, and whether the types of treatments they provide fit well with your needs.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study did not provide support for a pay-for-performance scheme in England, although these and other value-based payment models may offer promise in treatment systems like the United States where reimbursement of services is done by a mix of public and private entities rather than single payer system. Implementing these new payment models may be challenging from the provider perspective. Preliminary data suggests more work is needed to understand how and whether these types of payment models are feasible, cost-effective, and improve patients’ outcomes.

- For scientists: Many healthcare systems are shifting from fee-for-service payment models to value-based payment models, and these types of payment models have many theoretical advantages for the substance use disorder field. Future research might conduct qualitative investigation to help better understand the motivations, experiences, and implementation challenges of program managers and clinicians reimbursed under this type of program model. Future research might also examine different designs of pay-for-performance schemes, such as schemes that are based on process measures or a mix of process and outcomes measures.

- For policy makers: Given mixed findings for the effectiveness of pay-for-performance schemes and other value-based payment models along with theoretical advantages, pilot programs to identify strategies that address implementation challenges and optimal model designs may ultimately produce public health benefit. More research is needed before definitive policy implications can be formulated and widespread adoption should be pursued.

CITATIONS

Mason, T., Whittaker, W., Jones, A., & Sutton, M. (2021). Did paying drugs misuse treatment providers for outcomes lead to unintended consequences for hospital admissions? Difference-in-differences analysis of a pay-for-performance scheme in England. Addiction, 116(11), 3082-3093. doi: 10.1111/add.15486