Relapse Prevention (RP) (MBRP)

All treatments for substance use disorder (SUD), in a way, are intended to prevent relapse. The treatment called Relapse Prevention (RP), however, refers to a specific intervention.

Relapse Prevention is a skills-based, cognitive-behavioral approach that requires patients and their clinicians to identify situations that place the person at greater risk for relapse – both internal experiences (e.g., positive thoughts related to substance use or negative thoughts related to sobriety that arise without effort, called “automatic thoughts”) and external cues (e.g., people that the person associates with substance use).

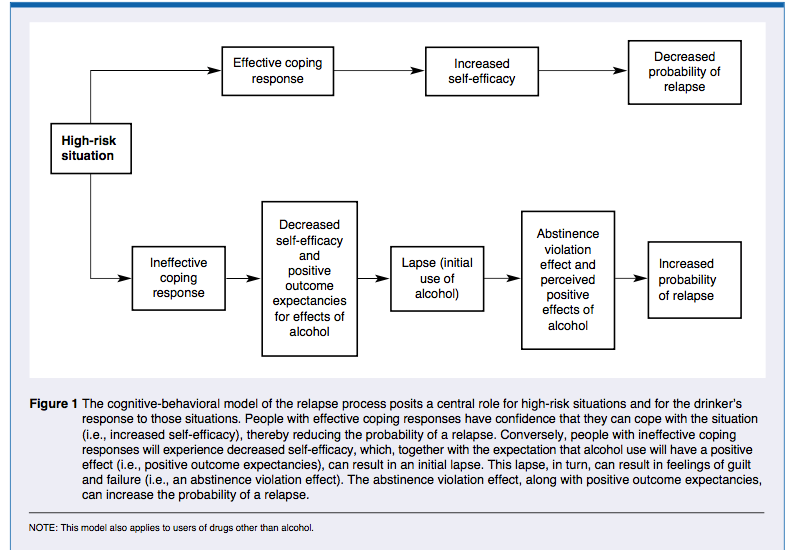

Then, the patient and clinician work to develop strategies, including cognitive (related to thinking) and behavioral (related to action), to address those specific high-risk situations. With more effective coping, the patient develops increased confidence to handle challenging situations without alcohol and other drugs (i.e., increased self-efficacy).

WHAT HAPPENS IN RELAPSE PREVENTION?

In Relapse Prevention (RP), the clinician and patient work first to assess potential situations that might lead to drinking or using other drugs. These situations include, for example, social pressures and emotional states that could lead to thoughts about using substances, and ultimately to cravings and urges to use.

These potentially risky situations are known as “triggers.” Patients and clinicians also aim to identify lifestyle factors that affect the likelihood of encountering these triggers (e.g., health behaviors like eating and sleeping, as well as one’s group of friends). RP clinical protocols typically include 12 weekly sessions, and are empirically supported when delivered over that time frame.

Relapse Prevention Strategies Include:

- Building awareness around the potential negative consequences of encountering high-risk situations and thoughts that associate substance use with good outcomes (i.e., it challenges positive expectancies surrounding substance use)

- Helping the patient to develop and expand their repertoire of coping skills that address specific high-risk situations for relapse (often called “triggers”), whether those situations lead to drug use-related thoughts, feelings, or bodily sensations

- Skills range from techniques to communicate with others when in a risky situation (e.g., how to confidently and comfortably say “no” to a drink if it is offered, called “assertive drink and drug refusal”), to “urge surfing,” a technique to help individuals cope with the intense longings to consume the substance that occurs during cravings

- Planning for “emergencies.” That is, unexpected situations where the patient finds themselves suddenly struggling to abstain from drinking or using other drugs

- Assessing and reinforcing the patient’s confidence in his/her ability to abstain from substance use, even in the face of challenging situations (e.g., self-efficacy)

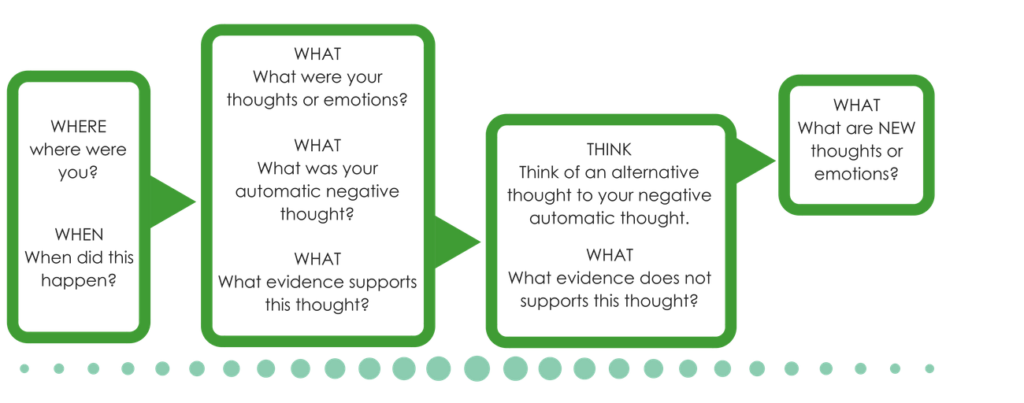

- Finding alternative ways of thinking about positive thoughts related to substance use, and negative thoughts related to abstinence, sometimes called “cognitive restructuring.” This activity includes discussing the thinking “traps” (sometimes called cognitive distortions, or unhelpful thinking styles) that can develop after years of drinking and using other drugs. See visuals below for examples of how this work might look

The clinician will use a range of strategies to facilitate these activities. For example, in Relapse Prevention – and many of the cognitive-behavioral approaches – role playing is common. This means in RP, the clinician and patient may act out an upcoming or common “real-life” situation to help with skill practice and application.

The patient should also expect to do work honing and practicing these skills outside of session – this is sometimes referred to as “homework,” “practice,” or simply “outside activities.” These outside activities could include thought journaling that asks patients to draw their awareness to, and work to change ways of thinking about their substance use, or include putting into practice any number of strategies to address potentially high-risk situations (e.g., exercise to cope with anxious feelings that may trigger thoughts about drinking, drink refusal skills at a social gathering, or calling someone from their support network).

EXAMPLE EXERCISE

One particularly notable innovation to the Relapse Prevention (RP) model is Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP). In this related approach, clinicians teach patients mindful meditation to help them cope with potentially triggering thoughts, feelings, and situations.

These mindfulness skills are intended to help the patient increase their awareness of cravings and other unpleasant feelings without judgment of the feelings as “bad” or necessitating a reaction. From this perspective of experiencing feelings and bodily sensations without acting on them, the patient may decide to engage in a healthier alternative activity, or even simply “sit with the feeling.” Typically, MBRP clinicians have their own meditation practice and use mindfulness skills in their own day-to-day lives.

WHAT IS THE THEORY BEHIND RELAPSE PREVENTION?

- Substance use has become the predominant coping response to meeting life’s challenges. Consequently, individuals with a substance use disorder cannot stop using because they lack the skills needed to cope with these challenges. The key to initiating and sustaining abstinence – that is, preventing relapse – is to develop a range of skills to cope with anticipated and potentially unforeseen challenges.

- As people accumulate successful recovery experiences, their confidence or self-efficacy in solving life’s problems without substances increases, thereby making it increasingly more likely that they will choose to avoid or be able to cope with high-risk situations.

- One assumption in RP models is that individuals are already motivated for abstinence or to reduce their drinking. Thus some evidence-informed clinicians may also use Motivational Interviewing (MI) or Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) to address the varying levels of readiness to change that patients might possess when they present to treatment.

WHAT ARE THE ORIGINS OF RELAPSE PREVENTION?

Developed in the 1980s by G. Alan Marlatt, and outlined in the 1985 text published with Judith Gordon, RP is based not only on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for other psychiatric disorders, but also on Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). This theory emphasizes the importance of personal belief in the ability to remain substance-free (i.e., abstinence self-efficacy), the tangible and intangible rewards from successfully coping without substances, and the importance of managing one’s external environment (e.g., social situations) in the maintenance of health behavior change.

Relapse Prevention is considered among the most important clinical innovations in the substance use disorder treatment and recovery field, and continues to be one of the most widely practiced. When clinicians and scientists refer generally to CBT for substance use disorder, it is often Marlatt’s RP model or some related approach to which they are referring. Specifically regarding Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP), Marlatt and his junior colleagues who would continue this work, including Katie Witkiewitz, developed this RP therapeutic approach by building on clinical research in the area of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression.

EVIDENCE FOR RELAPSE PREVENTION

Standard Relapse Prevention (RP) has strong empirical support as a helpful intervention for substance use disorder and works about as well as other active substance use disorder treatment approaches. Mindfulness-based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) appears to be as helpful as standard RP; more research is needed to determine whether MBRP offers greater benefit than standard RP.

RP FOR: ADOLESCENTS

Structured therapies have combined Relapse Prevention (RP) in a group format with individual sessions of motivational interviewing in adolescents with cannabis use disorder (motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, or MET/CBT). RP skills in MET/CBT include assertive drink and drug refusal, strategies to obtain social support, developing a plan for fun sober activities, and problem solving for high-risk situations and a lapse if it occurs.

While adolescent patients receiving a 5-session MET/CBT are likely to improve in terms of abstinence from all drugs including alcohol, they do not benefit from this intervention any more than other empirically-supported adolescent interventions (like the Adolescent-Community Reinforcement Approach), and even show about the same benefit as adolescents who receive a more intensive, 12-session version of MET/CBT with additional skill building. That said, particularly for the briefer MET/CBT, these interventions are likely to be more cost-effective than comprehensive family therapies that require many more clinical resources to achieve similar outcomes.

RP FOR: ETHNO-RACIAL MINORITIES

Preliminary evidence suggests Black and Latino individuals may not derive as much benefit from Relapse Prevention (RP) as White individuals. The studies on which this evidence is based, however, were not designed specifically to test this question of differential benefit. More research is needed to understand whether ethno-racial minorities show differential benefit, and if so, whether culturally adapted versions of RP can help address it.

- CITATIONS

-

- Dennis, M., Godley, S. H., Diamond, G., Tims, F. M., Babor, T., Donaldson, J., . . . Funk, R. (2004). The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27(3), 197-213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005

- Grant, S., Hempel, S., Colaiaco, B., Motala, A., Shanman, R. M., Booth, M., . . . Sorbero, M. E. (2015). Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for substance use disorders: A systematic review. RAND National Defense Research Institute Report.

- Litt, M. D., Kadden, R. M., Cooney, N. L., & Kabela, E. (2003). Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 118-128. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.118

- Marlatt, G. A., & Gordon, J. R. (Eds.). (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press.

- Morgenstern, J., & Longabaugh, R. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: A review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction, 95(10), 1475-1490. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951014753.x