Capitalizing on the window of opportunity: Shorter wait times associated with increased linkage to buprenorphine treatment

Opioid overdoses continue to rise in the United States and most individuals with opioid use disorder do not receive any type of treatment. Yet, for many different reasons, such individuals can end up in a hospital setting, providing an opportunity to start a conversation and engage them with opioid use disorder treatment while in the hospital or quickly following discharge. Hospital bedside addiction consultations are one innovative model that might help capitalize on this window of opportunity. In this study, researchers examined if a shorter wait time for a follow-up appointment after discharge for those hospitalized with an opioid use disorder and seen by an addiction consult service was associated with improved linkage to buprenorphine treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The opioid crisis has claimed nearly 450,000 lives in the last 20 years, with recent evidence showing that overdose deaths reached an all-time high in 2019 and preliminary evidence suggesting that the coronavirus pandemic has further exacerbated these deaths. Medications for opioid use disorder, such as methadone and buprenorphine (typically prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), are empirically-supported treatment options that decrease mortality. Despite this evidence, only 20% of individuals with opioid use disorder in the United States receive any treatment and only a third of these treated individuals receive opioid use disorder medication. Innovative models have emerged to address this treatment gap, including utilizing recovery coaches in medical settings, post-overdose response teams, and addiction consult services in the general medical healthcare system.

In fact, individuals with substance use disorders are overrepresented in general medical settings making these types of clinical venues opportune ones for perhaps beginning a conversation about the potential to obtain opioid use disorder treatment. One hospital-based intervention, known as an inpatient addiction consult service, provides assessment and treatment to patients who are in the hospital for some kind of medical reason but are not there seeking substance use disorder treatment.

Inpatient addiction consult services.

In addition, this type of service usually has a robust referral network to facilitate a “warm handoff” to outpatient care after hospital discharge, meaning service providers in the hospital make the outpatient appointment for (or with) the patient while they are still in the hospital.

Previous research suggests that this type of service is promising in improving outcomes among those with substance use disorders. One study found that patients with a substance use disorder seen by an addiction consult service were twice as likely to engage in treatment following hospital discharge, with those with opioid use disorder (one type of substance use disorder) 83% more likely than those without an opioid use disorder to engage in treatment. In addition, research has suggested that increased wait times for initiating outpatient substance use disorder treatment are associated with decreased likelihood of showing up for the initial appointment. This may because the longer people have to wait for an appointment the greater the likelihood they may lose their current motivation, get distracted, or succumb to powerful cravings and reinitiate their former pattern of problem substance use.

In this study, researchers examined if fewer days to outpatient appointment after discharge was associated with improved linkage to buprenorphine treatment among those with opioid use disorder who were seen by the inpatient addiction consult service and either recommended to seek buprenorphine treatment or initiated on buprenorphine in the hospital, and if other factors influenced this relationship. Ensuring linkage to treatment with evidence-based medications such as buprenorphine has the potential to decrease opioid morbidity and mortality.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a retrospective chart review of patients with opioid use disorder who were seen by the inpatient addiction consult service and either recommended to seek buprenorphine treatment or initiated on buprenorphine in the hospital then referred to outpatient treatment at a low-barrier addiction clinic. The study had two main aims: 1) to examine sociodemographic factors and clinical characteristics that were associated with wait time to their first buprenorphine appointment after discharge and 2) controlling for these sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, whether fewer days to the first outpatient appointment after hospital discharge was associated with a greater likelihood of attending the first buprenorphine appointment.

The main outcome was whether patients arrived at their first outpatient appointment after hospital discharge. This was a dichotomized variable (either “arrived” or “did not arrive”) and patients were classified as not arriving if they cancelled their appointment, even if they rescheduled. The primary independent variable of interest was the time patients had to wait between hospital discharge and the outpatient appointment, measured as the number of nights patients waited between the date of their hospital discharge and the date of their follow-up appointment post-discharge. This variable was dichotomized as either “0-1 days” representing same-day or next-day appointments or “2+ days” representing two or more days wait time for an appointment. Other data extracted from the electronic medical record included age, gender, distance from the hospital, type of insurance, presence of a co-occurring alcohol use disorder (presumably based on clinical judgment and evaluation, though the assessment they used to determine alcohol use disorder was not specified), and whether or not the patient was discharged with a buprenorphine prescription.

Inclusion criteria for the study included: being an adult inpatient (18+) at Boston Medical Center with an opioid use disorder (presumably based on clinical judgment and evaluation, though the assessment they used to determine opioid use disorder was not specified) from July 2015 to August 2017; being seen by the addiction consult service and either recommended, or recommended and initiated on, buprenorphine, and given a follow-up appointment to a low-barrier outpatient addiction clinic at Boston Medical Center upon hospital discharge. Exclusion criteria for the study included: discharged to another facility; inability to verify appointment data; outpatient appointment was for a reason other than opioid use disorder treatment; and patient had a premature discharge prior to scheduling the outpatient appointment at the low-barrier access addiction clinic (i.e., left against medical advice).

The sample included 142 patients that met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients were primarily middle-aged and identified as male. More than two-thirds were Medicaid beneficiaries, more than three-fourths were discharged with a buprenorphine prescription, and around 10% had a co-occurring alcohol use disorder.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Time to first buprenorphine appointment was unrelated to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

None of the sociodemographic or clinical characteristics included in analyses were associated with appointment wait time. Of note, for example, type of insurance (e.g., Medicaid, commercial, etc.) was unrelated to appointment wait time.

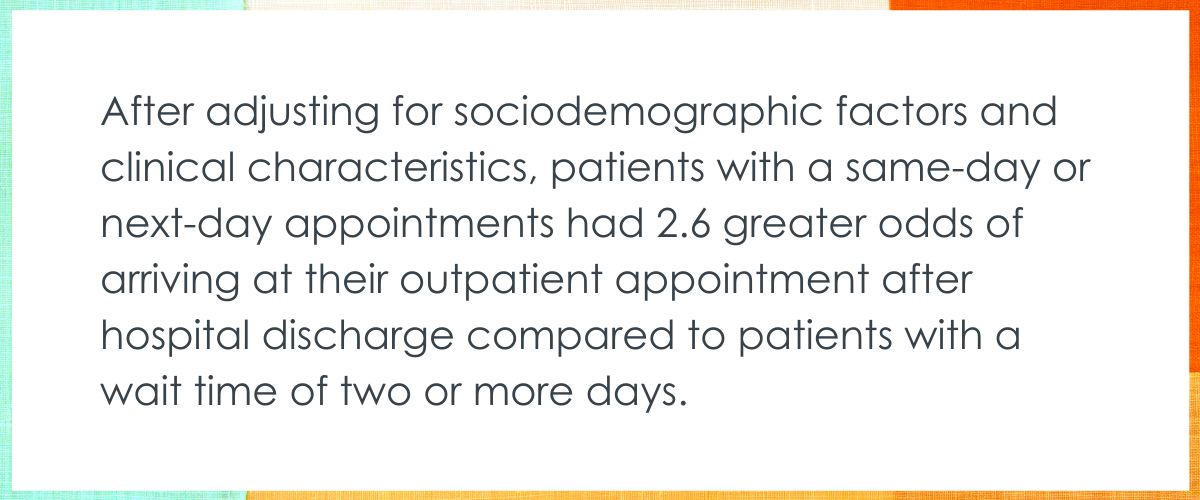

Shorter wait times, but not other characteristics, predicted showing up for the initial outpatient appointment.

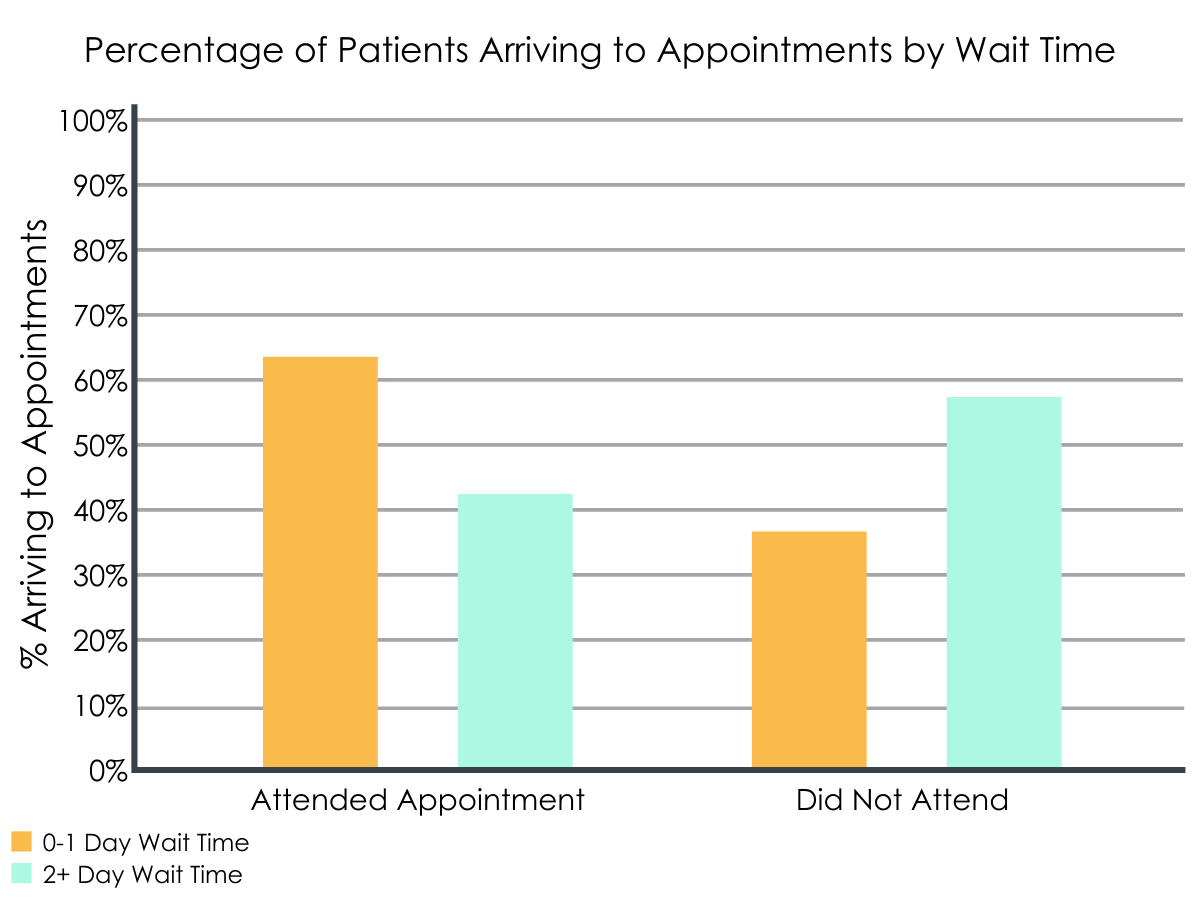

Of the 142 patients included in the study, only 77 (54%) arrived at their outpatient appointment. Of those who arrived at their outpatient appointment, 63% of patients had wait times of 0-1 days and 42% of patients had wait times of two or more days. After adjusting for sociodemographic factors and clinical characteristics, patients with a same-day or next-day appointments had 2.6 greater odds of arriving at their outpatient appointment after hospital discharge compared to patients with a wait time of two or more days.

Age, gender, distance from hospital, the type of insurance, presence of a co-occurring alcohol use disorder, and receiving a buprenorphine dose at discharge was unrelated to arriving at the initial outpatient appointment. Of note, while receiving a buprenorphine prescription upon hospital discharge was unrelated to showing up for the initial outpatient appointment (i.e., relationship was not statistically significant), descriptively, those discharged with prescription, on average, were 2.2 times more likely and those with alcohol use disorder 1.9 times more likely to arrive at their appointment, irrespective of wait time, but there was quite a lot of variability in these estimates.

Percentage of patients arriving to appointments by wait time.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The findings of this study suggest that patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service who received a same-day or next-day outpatient appointment for buprenorphine treatment after hospital discharge were more likely to attend that appointment compared to patients waiting two or more days for an appointment.

Based on the study’s findings, being able to provide same-day or next-day outpatient appointments after hospital discharge by increasing clinic availability to initiate or continue buprenorphine could improve continuity of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

This finding of quicker follow-up appointment availability being a good idea is not limited to addiction treatment, as similar findings have been shown for outpatient gastroenterology visits and in an outpatient ophthalmology clinic. Capitalizing on a window of opportunity using an inpatient addiction consult service followed by a same-day outpatient treatment makes sense and holds promise. It is unclear why some patients received shorter wait times to their first appointment than others. It is possible, given any resource limitations, that higher risk patients were prioritized. For example, younger individuals are more challenging to engage and retain in buprenorphine treatment. Any clinical decision-making that informed wait time decisions cannot be determined, but warrant further study.

It is notable that only around half of patients, regardless of wait time, showed up for their outpatient appointment highlighting significant room for improvement. A portfolio of interventions is needed to address the opioid use disorder treatment gap, and this innovative model may be one of these interventions.

The clinic that patients were referred to starting in August 2016 is called an opioid urgent care clinic, and is a unique setting where low-threshold treatment is available in near real-time. This clinic is co-located to the hospital, open Monday through Friday during normal business hours, is staffed with healthcare practitioners that can both initiate and prescribe buprenorphine, and has a strong referral network to wraparound services to holistically treat the individual. This type of clinic treats underserved populations (e.g. people experiencing homelessness), distributes naloxone to all of its patients, aims to minimize the myriad barriers to treatment, and is designed to serve as a “bridge” from the hospital or emergency department to an outpatient setting. This model may be worth considering in urban, safety net hospital.

This study only measured linkage to treatment from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. Even though linkage to treatment is the first step to treatment retention, there is strong evidence that increasing the time on opioid use disorder medication leads to the largest reductions in mortality. For instance, emergency department-initiated buprenorphine has emerged as a promising intervention and shows increased engagement in treatment after the first 30 days, but retention in treatment after six months is no different than those who were referred to treatment, rather than initiated, in the emergency department. This highlights that initiation on medication is necessary but not sufficient to improve outcomes for those with opioid use disorder. Strategies that increase treatment retention are needed and may include extended-release formulations and adjuncts to medication treatment such as digital technologies, contingency management, and recovery coaching.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- During the time period of the study, patients were referred to two different clinics. For the first part of the study, they were referred to a once-weekly clinic. In the latter part of the study, they were referred to a clinic that was open during the weekdays. Researchers reported that they did not adjust for the clinic patients were referred to because the clinic type was collinear with the primary exposure (i.e., there was no variation for the model to analyze). Descriptive analyses for each clinic may have added important context to the study findings.

- Generalizing the findings of this study should be done with caution. The was a retrospective study, which is a study design that cannot make causal determinations based on the findings had a small sample size, more than two-thirds of the sample were Medicaid beneficiaries, and the study took place in one healthcare facility (Boston Medical Center) that has a low-threshold opioid urgent care clinic co-located to the hospital.

- The wait time included weekends when the clinic would not have been accessible, meaning that patients discharged on a Friday would automatically be classified as having an appointment two or more days after discharge.

- Some patients were likely initiated on buprenorphine in the hospital, which may have affected arrival to the initial outpatient appointment, though they would have only been given enough of the medication to get them to their first outpatient appointment.

- Patients were classified as not arriving to their initial appointment even if they cancelled and rescheduled. It’s possible that these individuals did attend a later appointment.

- The dataset the researchers used was limited to buprenorphine, one of three types of medications for opioid use disorder. Patients may have decided to attend a methadone clinic after discharge, which would not have been captured in this study. Also, the data set did not report important variables such as race/ethnicity and housing status.

BOTTOM LINE

The findings of this study suggest that patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service who received a same-day or next-day outpatient appointment for buprenorphine treatment after hospital discharge were more likely to attend that appointment compared to patients waiting two or more days for an appointment. Adding to existing research showing linkage to treatment with evidence-based medications such as buprenorphine has the potential to decrease opioid morbidity and mortality, this study suggests the timeliness of this linkage might make a difference – the quicker the better.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Hospital admissions offer a chance to connect individuals with opioid use disorder to evidence-based treatment regardless of the initial reason for hospital admission. The inpatient setting may be an important opportunity to engage those who may not otherwise seek treatment for their opioid use disorder or be seeking it at that particular time despite the fact that they benefit from it. Upon discharge, it is crucial that individuals who are either initiated on buprenorphine or recommended to begin treatment in an outpatient setting are linked to continuing care.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: An inpatient addiction consult service combined with a low-threshold outpatient addiction clinic that is co-located to the hospital is an innovative and promising model to initiate and engage individuals with opioid use disorder in evidence-based treatment. This new treatment engagement model is being implemented by a number of hospitals and healthcare systems in the United States, but the vast majority lack such programs. This model may be especially worth considering in urban, safety net hospital.

- For scientists: Given the limitations of this study and the potential impact that this type of intervention can have on the opioid crisis, there are many opportunities for future research. Many important independent variables were collinear and were not able to be included in statistical analyses. Other important variables, such as race/ethnicity and social determinants of health, were not captured by the electronic medical records used for the retrospective chart review. Another consideration is that this study was done in a unique setting and without a sample that represents the general population, so it remains unclear if these same findings would be found in another healthcare facility or a healthcare system. Lastly, this study only measured arrival at an outpatient follow-up appointment after hospital discharge, which may serve as a proxy for initiation or engagement in buprenorphine treatment. More research is needs on how this translates to treatment retention and outcomes over time.

- For policy makers: Innovative models are urgently needed to address the opioid crisis, where overdose deaths continue to rise and the majority of those with opioid use disorders do not receive any type of treatment. Interventions are especially needed to improve linkage to treatment. An inpatient addiction consult service combined with a low-threshold outpatient addiction clinic that is co-located to the hospital may be one these interventions, which has shown promising results in some healthcare systems. Funding is needed to study promising interventions like this one with larger samples sizes and more rigorous study designs can help us to identify novel interventions for linking opioid use disorder patients to treatment, which can ultimately reduce opioid-related morbidity and mortality.

CITATIONS

Roy, P.J., Price, R., Choi, S., Weinstein, Z.M., Bernstein, E., Cunningham, C.O., Walley, A.Y. (2021). Shorter outpatient wait-times for buprenorphine are associated with linkage to care post-hospital discharge. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 224, 108703. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108703