Buprenorphine is more effective than methadone in reducing opioid use among patients with co-occurring mental health conditions

Many individuals with opioid use disorder also have co-occurring mental health conditions. Two commonly used agonist medications for opioid use disorder—buprenorphine and methadone—are effective in reducing opioid use as well as improving other psychiatric symptoms. This study compares the effects of each of these medications on reducing opioid use among patients with co-occurring mental health disorders.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

It is common for individuals with opioid use disorder to be diagnosed with other mental health conditions, particularly mood disorders, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or antisocial personality disorder. These co-occurring (also referred to as “comorbid”) mental health conditions may impact the outcomes of treatment for opioid use disorder. However, the existing data is mixed, with some studies suggesting that comorbid conditions are associated with a higher risk of relapse, some studies suggesting that these conditions are associated with a lower risk of relapse and more time spent in treatment, and other studies suggesting there is no association between comorbidity and treatment outcome. This inconsistency in findings suggests that research examining specific co-occurring disorders and their impact on specific forms of treatment may be needed to understand the impact of comorbidity on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes.

Existing research has demonstrated that two commonly used agonist medications for opioid use disorder—buprenorphine and methadone—are effective in reducing opioid use. Researchers have also found that these medications can improve other psychiatric symptoms by their impact on receptors in the brain that also impact mood and anxiety levels. Specifically, buprenorphine may show an antidepressant effect by its antagonism of kappa-opioid receptors and anti-anxiety effects through its agonism of nociception receptors. Likewise, methadone may affect mood by blocking reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, similar to antidepressant medications (e.g., fluoxetine). That being said, researchers have not yet rigorously studied whether one medication is better than the other in treating these patients, or if one medication may work better for a particular subset of these patients. A more nuanced understanding of these opioid use disorder medications’ effects can help improve practice through more tailored clinical recommendations that take co-occurring mental health disorders into consideration.

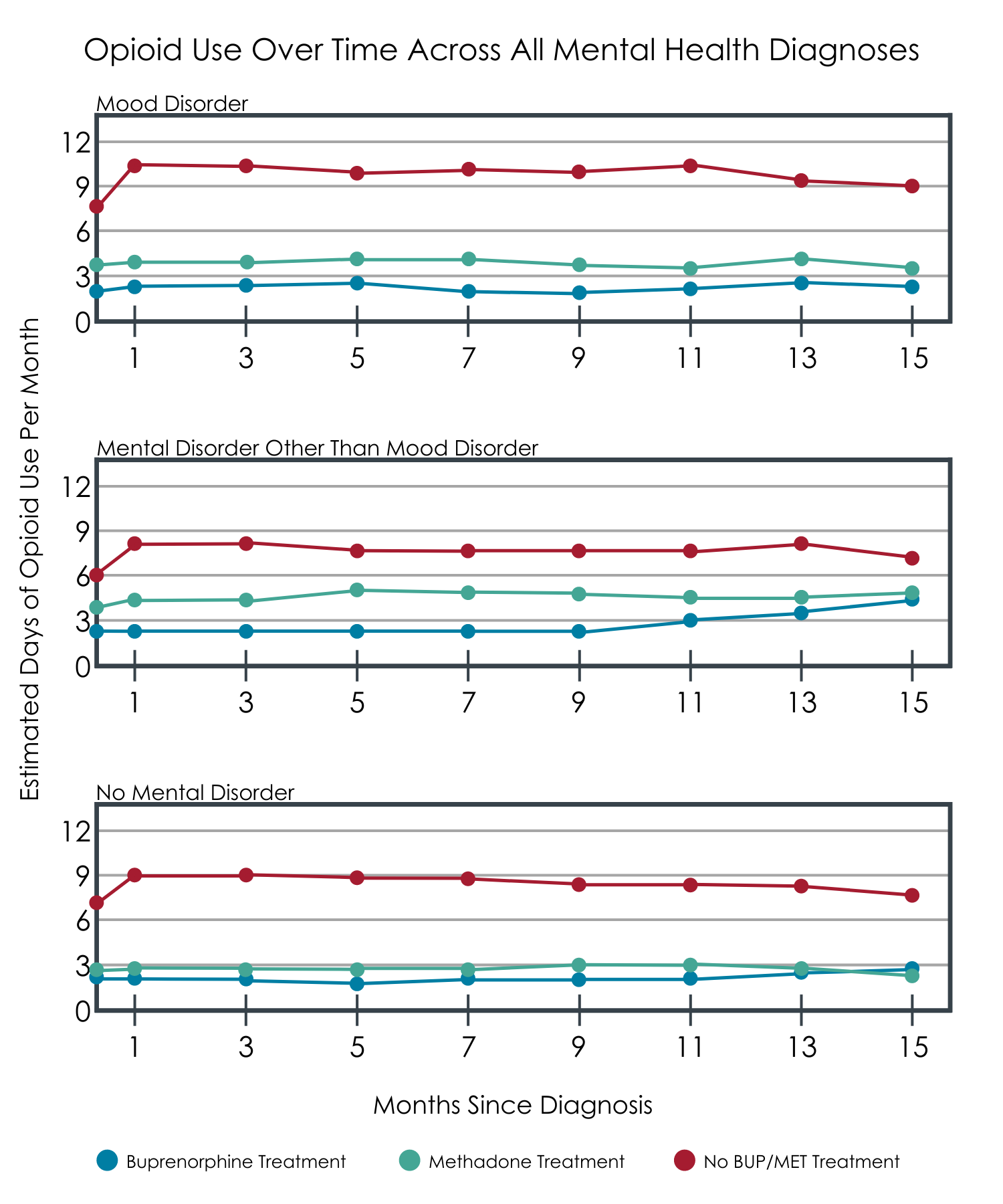

The researchers conducting this study used data from a large, multisite, trial to examine whether the effects of methadone and buprenorphine on reducing opioid use differ among: 1) patients with mood disorders, 2) patients with other types of mental health conditions, and 3) patients without a co-occurring mental health condition.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the Starting Treatment with Agonist Replacement Therapies (START), a large, multi-site, randomized controlled trial initially designed to compare the effects of buprenorphine and methadone on liver function. Previous secondary analyses of this study, also by Hser and colleagues, found that both treatments were effective in reducing opioid use over a long-term follow-up. The current study used data from 597 of the original 1269 participants. Participants in this secondary analysis were included because they completed the initial study, which involved 24 weeks of randomized treatment with either buprenorphine or methadone, as well as three yearly follow-up interviews.

The primary outcome studied was opioid use, which was determined by patients reporting on the number of days per month they used opioids in the follow-up period between the second and third interviews. After the initial study period was over, patients were free to pursue the treatment of their choosing (including no treatment), and they reported on any treatments they received for each of their follow-up interviews. Overall, on average participants reported a smaller percentage of months spent in buprenorphine treatment (11.5%) compared to methadone treatment (42.5%) or no medication treatment (43.2%). While it is possible individuals were attending treatment and/or recovery support services apart from these opioid use disorder medications during the 3-year follow-up, the research team did not include service utilization apart from agonist treatment nor was it included in their analyses.

Study participants completed a structured assessment of co-occurring mental health conditions based on the 4th edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, or DSM-IV, at the second follow-up interview and were placed in one of three groups based on the presence/absence of lifetime mental health disorders: 1) patients with mood disorders (e.g., major depression or bipolar disorder), 2) patients with mental health disorders other than mood disorder (e.g., anxiety disorder, antisocial personality disorder), or 3) patients with no co-occurring mental health disorder. Of the 597 participants, around half (50.6%, n=302) had mood disorder, 19.1% (n=114) had a lifetime mental health disorder other than mood disorder, and 30.3% (n=181) did not have a co-occurring mental health condition. In the mood disorder group, 56% had bipolar disorder and 44% had major depressive disorder, and many had other co-occurring disorders, including anxiety, personality, psychotic, and eating disorders. In the other mental health disorder (excluding mood disorder) group, the most common diagnoses were anxiety disorder (69.3%) and antisocial personality disorder (43.8%), with a small proportion of patients having psychotic disorder (6.1%).

Researchers used statistical analysis to examine the relationships between opioid use, mental health diagnosis (defined as belonging to one of the three aforementioned groups), and treatment type (buprenorphine, methadone, or neither) over the follow-up period. Because the primary outcome (number of days with opioid use) contained a large number of zeroes (i.e., days without use), a special type of statistical modeling was used to account for this pattern of data. This type of analysis involves two steps, one looking at a binary outcome (any or no use in a given month) and the other looking at a continuous outcome (number of days of use in each month). Because participants could choose to receive buprenorphine or methadone or neither during the follow-up, the study team controlled statistically for factors to isolate the effect of medication on opioid use as best they could, including the site where they participated in the initial trial and medication to which they were randomly assigned, as well as age, gender, race/ethnicity, cocaine use in the past 30 days (yes/no), and injection drug use in the past 30 days (yes/no) at study intake.

These participants were 63.8% male, 72.4% White, and had an average age of 37.9 years. At baseline, 65.3% of participants reported a history of injection drug use in the prior 30 days and 31.5% reported history of cocaine use in the prior 30 days. In the initial study, 57.5% of studied participants were randomized to receive buprenorphine (vs. methadone).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

The three mental health disorder groups had similar rates of opioid use over follow-up but differed regarding the amount of treatment they received.

The three mental health disorder groups were similar on number of days per month of opioid use during the follow-up period. Participants with mood disorder spent a larger percentage of time taking medication for opioid use compared with participants without a mental health condition.

Buprenorphine, but not methadone, outperformed no medication in all three groups.

In models examining the effects of mental health diagnosis group and treatment on opioid use over follow-up, buprenorphine and methadone were both associated with reduced opioid use for those in the mood disorder and no co-occurring mental health disorder groups when compared to participants who were not receiving any medication for opioid use disorder. For those with a mood disorder, compared to no medication treatment, receiving buprenorphine was associated with a 76% reduced likelihood of any opioid use and 20% fewer opioid use days. By comparison, among those with mood disorders, receiving methadone was associated with a 53% reduced likelihood of any opioid use and 28% fewer opioid use days. Only buprenorphine (not methadone) was associated with reduced opioid use in the group with co-occurring mental health disorders other than mood disorders. For those with a mental health disorder other than a mood disorder, compared to no medication treatment, receiving buprenorphine was associated with 62% fewer opioid use days.

Buprenorphine was associated with greater reductions in opioid use than methadone across all mental health diagnosis groups.

In analyses that included only participants who received either buprenorphine or methadone (excluding those with no medication treatment), buprenorphine was associated with a lower likelihood of using opioids among those in the mood disorder and without co-occurring disorder groups, compared to methadone. In the mental health disorder other than mood disorder group, buprenorphine was associated with fewer number of days using opioids when compared to methadone.

Adapted from Hser et al., 2022.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

There is limited existing research comparing the effectiveness of buprenorphine vs. methadone for individuals with opioid use disorder who have a co-occurring mental health disorder, such as major depressive disorder. The findings of the current study suggest that among patients treated with medications for opioid use, buprenorphine appears to be more effective than methadone for patients with and without co-occurring mental health disorders. Specifically, buprenorphine treatment was more strongly associated with abstinence from opioids among patients with mood disorders and those without comorbid mental health disorders and was also associated with fewer monthly days of opioid use among those with mental health disorders other than mood disorder. Importantly, patients treated with either buprenorphine or methadone had less opioid use when compared with patients who had no medication treatment, regardless of diagnostic group.

Medications for opioid use disorder may also impact co-occurring symptoms. In addition to impact on opioid receptors, the neurochemical mechanisms of agonist medications for opioid use disorder likely involve other receptors in the brain that can influence mood, anxiety, and other psychiatric symptoms. Buprenorphine in particular may have more impact on receptors associated with anxiety, with at least one study demonstrating that patients with PTSD and opioid use disorder treated with buprenorphine saw reductions in PTSD symptoms, whereas patients treated with methadone did not see similar improvements in PTSD symptoms. This could explain how in the current study some treatment effects were only seen for buprenorphine within the group characterized by mental health conditions other than mood disorders.

These findings speak to the enhanced effectiveness of buprenorphine, particularly for patients with co-occurring disorders other than mood disorders, and likewise the importance of continuing to increase accessibility to this effective form of treatment. In the present study, a relatively small proportion of patients received buprenorphine, which the authors indicate may have been due to availability of this treatment in certain geographic areas. Notably, the original data collection took place in 2006-2009, and buprenorphine has become more available since then. Other recent research has suggested that buprenorphine is associated with a lower mortality risk compared to methadone, suggesting other public health advantages to this treatment. That being said, both this and other studies indicate that both forms of agonist medication treatment for opioid use disorder are generally effective and better than no treatment. Therefore, the advantage of one treatment over another for a particular patient may boil down to the treatment that is available, able to be accessed on a regular basis, and well-tolerated by the patient.

Although the current study is an important advancement of the literature on differential treatment effects, there are additional factors to consider. First, since the trajectory of co-occurring mental health disorders was not assessed alongside opioid use, it remains unknown whether changes in these symptoms impacted opioid use in study participants, change in opioid use impacted psychiatric symptoms, and/or the presence of co-occurring disorders impacted treatment in some other way (e.g., by increasing or decreasing adherence).

Similarly, this study only examined the impact of lifetime mental health diagnoses. It is unclear if these conditions were active at the time of intervention and if examining current comorbidities would have influenced results in a different way. Additionally, this study did not include measures of participant involvement in other types of services for opioid use disorder (e.g., behavioral interventions or community-based mutual-help organizations) or services such as therapy and medication for co-occurring mental health disorders. Thus, it is difficult to isolate the effects of the agonist medication vs. these other factors in this dual-diagnosis population.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The researchers did not have or include information about the treatments that participants did or did not receive for their co-occurring mental health conditions, or services apart from medications for opioid use disorder, which could possibly have an effect on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes.

- Participants were randomized to treatment in the initial study phase but not during follow-ups. Information on treatment type and status were derived from participant self-report, which can be subject to bias or errors in retrospective reporting.

- Additionally, data came from participants who were able to provide data at all follow-up periods. Participants in the subset sample did differ significantly from the full sample in terms of demographic factors, substance use history, randomization history; however, the groups did differ on gender (females more represented in the subset). Thus, these findings may not apply to all individuals with opioid use disorder.

- The study did not examine changes in symptoms related to mental health conditions, which may also be related to changes in opioid use over time and could be impacted by medications for opioid use disorder. Additionally, mental health disorder groups were based on lifetime vs. current diagnoses; a study with a focus on concurrent disorders/symptoms may have different results.

- The initial study was conducted more than a decade ago, when availability of buprenorphine treatment was much lower than present-day, likely limiting the proportion of study participants receiving this treatment and possibly impacting the differential treatment effects.

- Although this study demonstrated statistical differences between treatments, the real-world clinical significance of these differences is still uncertain.

BOTTOM LINE

Both buprenorphine and methadone appear to reduce opioid use compared to no medication treatment. When directly compared, buprenorphine may be more effective than methadone, particularly for patients with certain co-occurring mental health disorders that have occurred as some point during their life.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: If you are interested in reducing opioid use, both methadone and buprenorphine appear to be effective medication treatment options, although buprenorphine was somewhat more effective in the present study. If you have a lifetime co-occurring mental health disorder that is not a mood disorder (e.g., an anxiety disorder, OCD, PTSD, antisocial personality disorder, or psychotic disorder), there may be advantage in pursuing treatment with buprenorphine vs. methadone if it is available to you.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: It is important to assess any co-occurring mental health conditions with patients who are seeking to reduce opioid use. Based on patient’s lifetime mental health diagnosis, prescription of buprenorphine may be a preferred approach (particularly for patients with co-occurring conditions that are not mood disorders), but more research is needed to determine whether this match is robust.

- For scientists: This study showed that buprenorphine was somewhat more effective than methadone across patient groups, although the clinical significance (vs. statistical significance) of these findings remains uncertain. It will be important for future work to examine the dynamic relationship between concurrent psychiatric symptoms and opioid use patterns as a function of treatment type. It will also be important to examine these effects in other substance use disorder treatment modalities beyond agonist medications. Similarly, future work would benefit from examining adherence to treatment, how this may differ depending on type of comorbidity, and the impact of adherence on outcome. A more granular approach to comorbidity (e.g., examining the differential effects of anxiety disorder vs. personality disorder and current diagnosis vs lifetime diagnosis) would likewise enhance understanding of the effect of specific conditions/symptom clusters on opioid use/treatment outcomes, which is lost in more heterogenous groups.

- For policy makers: Across patient groups, buprenorphine appears to be somewhat more effective than methadone, with an even greater advantage for certain patient group (e.g., those with co-occurring psychiatric disorders that are not mood disorders). It is likewise important that buprenorphine be a widely available treatment option for patients with opioid use disorder, ideally one that is able to be prescribed by providers who are working with patients on their co-occurring mental health difficulties.

CITATIONS

Hser, Y., Zhu, Y., Fei, Z., Mooney, L. J., Evans, A. E., Kelleghan. A., Matthews, A., Yoo, C., & Saxon, A. J. (2021). Long-term follow-up assessment of opioid use outcomes among individuals with comorbid mental disorders and opioid use disorder treated with buprenorphine or methadone in a randomized clinical trial. Addiction, 117(1), 151-161. doi: 10.1111/add.15594