Buprenorphine prescribing by nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants: Patterns and barriers

With specialized methadone clinics operating at capacity, office-based buprenorphine is recognized as the best option to meet a growing need for empirically supported treatment for opioid use disorder. Originally available only to physicians, Nurse Practitioners and Physicians Assistants gained access to the waiver allowing them to prescribe buprenorphine in 2016. Two years later, the authors of this study sought to examine prescribing practices and barriers among the providers who completed the waiver process.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications for opioid use disorder, including methadone and buprenorphine, are empirically supported treatments that reduce risk of overdose and death and improve daily functioning. While methadone treatment is provided in specialized clinics and generally requires daily visits during early treatment, buprenorphine can be prescribed in a primary care or other medical clinic, and practice guidelines advise weekly visits during early treatment, and monthly visits are common after an initial treatment period. The flexibility and empirical support of this treatment have led experts to highlight its potential role in making treatment for opioid use disorder more widely available. In 2016, Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physicians Assistants (PAs) gained access to the waiver required to prescribe buprenorphine. These providers serve important roles in primary care and specialty clinics, especially in rural areas where physicians are less accessible than in urban areas. The authors of this study had previously reported on data showing substantial variation in prescribing practices for physicians who completed the waiver process. They also reported on the various barriers to providing care that were reported by physicians. In the current study, the authors took a similar approach to examining prescribing practices and potential barriers to providing care among newly-waived NPs and PAs.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors conducted a single, cross-sectional survey, using the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration database to identify 1,572 NPs and PAs who had received a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine as of October 2018. This number represented all rural providers and a random sample of 500 urban providers. The authors later identified 247 of these providers who were not eligible for the study due to factors such as retirement or having moved from the original practice. Of the remaining 1,325 providers, 614 (46.2%) responded to the survey.

Survey questions mirrored the previous survey of rural physician buprenorphine providers, which asked about prescribing practices as well as some potential barriers to prescribing. Prescribing questions included history and current experience prescribing buprenorphine, the number of other waivered providers in the same practice, and acceptable referral sources for new patients. Providers were also asked to select from a list of potential barriers previously used by the authors (it’s unclear how this list, first cited in another study on barriers reported by physicians, was originally generated). The list included problems with insurance, clinic policies, and the policy limiting how many patients are allowed to be prescribed buprenorphine by a given provider at one time. Provider concerns about “diversion,” or the practice of sharing or selling prescribed medications to other people, were also included in the list of potential barriers. Finally, the researchers used providers’ zip code to determine (1) where their location fell along the continuum from urban to rural, and (2) whether they were subject to higher or lower level restrictions of practice such as the level of autonomy from physicians in providing prescription medications to patients.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

NPs and PAs who have a buprenorphine waiver actively treat individuals with opioid use disorder.

Of those surveyed, 80.3% had prescribed medication at any time, and 71.1% were accepting new patients at the time of the survey. Those who were waivered to treat 30 patients were treating 13.2 on average, while those who held the 100 patient waiver were treating an average 41.5 patients. Only 15%, however, had the waiver permitting treatment of 100 buprenorphine patients – all others were limited to 30 patients. More than half reported practicing in a primary care clinic, with about a quarter practicing in mental health settings, and the remainder in addiction and other specialty clinics. Most reported working in a practice with two to three other providers waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. Rural providers were more likely to accept Medicaid and cash payment for buprenorphine treatment, compared to their colleagues practicing in urban areas.

Barriers reported by providers included concerns about diversion, insurance issues, time constraints, and lack of available mental health or psychosocial support.

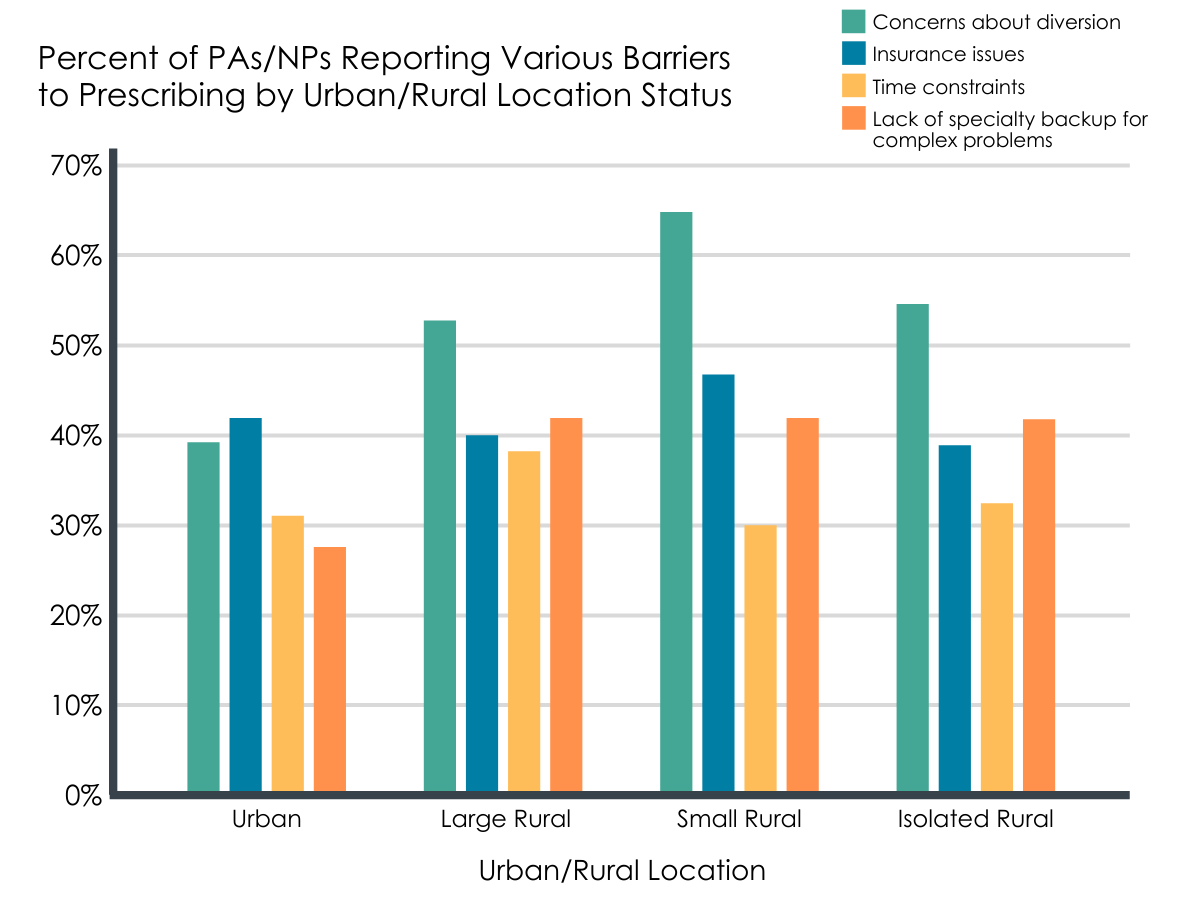

While the most common barriers were similar across the continuum from urban to isolated rural, a much larger percentage of rural providers expressed concerns about diversion and lack of specialty care backup. NPs in less restrictive states were more likely to report concern regarding availability of backup specialty care. Otherwise, level of restriction on the practice of NPs and PAs did not impact prescribing practices or barriers. Barriers also differed for those who had never or no longer prescribed buprenorphine. These providers reported higher rates of problems related to support within their clinic, and more concern about lack of access to specialty treatment.

Figure 1.

Compared to previous research on physicians who received the waver, NPs and PAs were more likely to be accepting new patients, treated more patients on average, and were less likely to have no patients on their roster.

However, about 20% of providers said they had never used their waivers, which is higher than physicians in the previous survey. Relative to physicians, NPs and PAs report similar barriers to prescribing buprenorphine, with administrative/state level policy barriers representing an additional challenge for NPs and PAs.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Allowing buprenorphine prescribing privileges for providers other than physicians is an important step towards increasing the availability of medication for opioid use disorder. This policy change has had an important impact, with another recent study showing that recent growth in buprenorphine providers in rural areas was driven by NPs and PAs. Additional efforts to increase treatment access are also underway, including a movement to remove the waiver requirement all together. However, as long as the waiver is required for buprenorphine prescribing, in showing that those who used their waiver were accepting higher caseloads compared to physicians, the current study highlights the value of adding NPs and PAs to the pool of providers for opioid use disorder medications. It is notable that only 15% had completed the additional process to increase their caseload to 100 patients, because there is evidence that providers who do so have the biggest impact on treatment access. There is a one-year delay for the application to increase patient capacity, so it is possible that more providers will complete this process as they reach this benchmark.

Barriers to prescribing included concerns about diversion, with rural providers reporting higher rates of diversion concerns relative to urban providers. While patients in one study of individuals who used diverted buprenorphine most commonly did so to stave off withdrawal, about half reported using buprenorphine to “get high or alter [their] mood”. At the same time, very few individuals identify buprenorphine as their drug of choice, and buprenorphine is known to reduce the risk for drug overdose by about 50%. Overall then, while there are indeed risks of buprenorphine diversion, the benefits of such diverted use (e.g., overdose risk reduction) may outweigh the risks (e.g., ongoing buprenorphine misuse). Also, if policies could reduce prescriber barriers, this might result in more instances of medically-supervised buprenorphine treatment for individuals with opioid use disorder, lowering the rates of diverted use. Extended release formulas, such as the monthly injectable form of buprenorphine (“Sublocade”) have shown promise in early clinical studies, and may also reduce provider concerns with respect to diversion.

Another barrier of particular concern in more rural areas was the lack of specialty care backup. This concern has been effectively addressed by the hub-and-spoke treatment model, developed in Vermont, which created a statewide network of “hubs” or specialty treatment centers which support the needs of “spokes” in primary care practices. Vermont has successfully increased access to care and reported promising patterns of successful transfers between specialty and primary care practices according to patient needs. Other states who are working to implement the Vermont model, such as California, have experienced some challenges with respect to provider support for treating opioid use disorder, and efforts are underway to enhance supports available for primary care providers in particular.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Of the potentially eligible providers contact by the researchers, only 43.9% responded to the survey. Consequently, it is unclear to what degree findings in this study can be generalized to all NPs/PAs. It is possible that responding providers differed from those who did not respond in important ways. For example, non-responders may be less involved in treating opioid use disorder, and rates of active prescribing may have been overestimated. It is also possible that providers with high caseloads were unable to find the time to respond to the survey, which highlights the difficulty of determining the potential effects of missing responses.

- The waiver to prescribe buprenorphine only became available to NPs and PAs approximately two years prior to the data collection for this study. It is possible that the barriers reported will impact prescribing practices in the longer term, and future work will need to continue to monitor practices as buprenorphine becomes a more established part of providers’ practice.

- While concerns about diversion represented a major barrier to prescribing, especially for rural providers, this survey did not identify the underlying source of this concern. Without knowing whether concerns are related to actual events that occurred within a providers’ practice, misunderstanding of the main drivers of medical diversion, or stigma-related issues, it is difficult to identify the most effective way to address this particular barrier.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: NPs and PAs are an important source of buprenorphine treatment, especially in rural areas. While many are providing this life-saving treatment, only 15% of those surveyed for this study were approved to treat up to 100 patients, with the rest limited to 30 patients. Providers reported a number of concerns regarding their ability to provide effective treatment for individuals with opioid use disorder, including diversion and mental health needs. It is important to try not to let this deter you from treatment, and to try to be willing to discuss providers’ concerns. Providers also report challenges with insurance company coverage, so taking an active role in advocating for your treatment with your insurance company may facilitate your medical care. Now that they are able to provide buprenorphine medication, practices which include NPs and PAs as providers may be a good setting to receive buprenorphine treatment, particularly if this results in better coverage and effective patient transfers if a provider were to leave a practice.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: NPs and PAs have become important sources of buprenorphine treatment in rural areas. For the most part, those who complete the waiver process do provide buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. However, most are limited to a caseload of 30 patients, with only 15% having completed the subsequent process to treat up to 100 patients. Providers report barriers consistent with broader concerns about their ability to effectively support the treatment needs of individuals with opioids use disorder. Improving access to specialist treatment referrals is an important goal for supporting these providers. States such as Vermont, which have implemented network models to facilitate transfers to high levels of care when needed, have reported increased treatment capacity following such efforts. When discussing concerns about medication diversion with patients, providers should consider keeping in mind that diversion is often driven by limited access to treatment, and illicit use of buprenorphine is more likely to be protective against, rather than a risk factor for, opioid-related overdose.

- For scientists: Since gaining access to the waiver process in 2016, NPs and PAs have become important resources for buprenorphine treatment, especially in rural areas. For the most part, those who complete the waiver process do provide buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. However, at the time of this survey, most providers were limited to a caseload of 30 patients, with only 15% having completed the subsequent process (after the required one-year delay) to upgrade to a 100 patient waiver. The barriers to providing treatment that were reported by providers in this study were largely descriptive, and thus there is limited information with respect to the source of, for example, concerns about diversion. Better understanding barriers that may be driven in part by stigma, concern about ability to provide effective treatment, or misunderstanding of consequences of diversion is an important next step. Furthermore, there is a need to develop, test, and disseminate training and practice support strategies for addressing the barriers reported by front-line buprenorphine providers.

- For policy makers: Since first gaining access to the waiver in 2016, NPs and PAs have quickly become an important source of buprenorphine treatment, especially in rural areas. Those who complete the waiver process do prescribe buprenorphine treatment for individuals with opioid use disorder, though it appears that few (15%) complete the subsequent application to upgrade to the 100 patient waiver. NPs and PAs report similar barriers to providing buprenorphine treatment as their physician colleagues. Providers working in rural settings had more concerns about diversion compared to providers in urban settings, and also reported concerns about access to backup specialty care. Concerns about diversion may be alleviated by increasing access to care, as buprenorphine diversion is likely driven, at least in part, by challenges with accessing legitimate forms of medication treatment. Also, increased funding and provision of extended release buprenorphine (e.g., “Sublocade”) might decrease diversion worries. Furthermore, consultation with treatment programs and scientists can guide allocation of resources (such as funding) towards efforts to identify and implement strategies for ensuring that waivered providers feel adequately supported in their ability to provide good clinical care and refer to specialty care when necessary.

CITATIONS

Andrilla, C. H. A., Jones, K. C., & Patterson, D. G. (2019). Prescribing practices of nurse practitioners and physician assistants waivered to prescribe buprenorphine and the barriers they experience prescribing buprenorphine. The Journal of Rural Health, [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12404