A deeper dive into the relationship between opioid prescribing guidelines, prescriptions, and opioid use disorder

There is consensus that increases in opioid prescribing have overexposed the population to opioids and played a substantial role in the overdose crisis in North America. This has led to tighter opioid prescribing regulations. Clarity on whether and how prescribing practices have changed, and updated data on the relationship between prescribing and opioid use disorder in context of these newer more restrictive guidelines can help improve clinical practice and public health recommendations. In this study, multiple databases were linked to identify cases of opioid use disorder in British Columbia, Canada. Initial opioid prescriptions among these cases were characterized prior to disorder identification with a focus on prescriptions that did not follow current guidelines.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

The opioid crisis in North America has worsened in recent years as opioid overdose deaths continue to increase in the United States and Canada. While there are myriad contributors to the overdose crisis and multiple waves over time (with fentanyl playing a major role in the current wave), there is expert consensus that increased opioid prescribing beginning in the mid-1990’s was among the earliest catalysts in what has become a complex, seemingly intractable public health emergency. In addition to increased prescribing overall, opioid prescriptions were written often for many more pills than necessary, often at higher doses, and for longer durations, overexposing the population to a potentially potent, seductive, and addictive drug. In fact, for people chronically taking prescription opioids, the strongest risk factors in developing opioid use disorder are dose and duration rather than individual-level factors -hence the phrase “risky drugs, not risky patients”, although in reality risk of addiction is often influenced by both drug factors and individual person-level risk factors. There is also strong evidence for the transition from prescription opioid use to heroin use among people with opioid use disorder, especially younger people engaged in non-medical prescription opioid use.

Recommendations for opioid prescribing have changed over time with more restrictive guidelines in recent years that recommend lower doses, fewer pills (meaning shorter durations for use), and no concomitant prescriptions for benzodiazepines, all of which lower the risk of overdose and addiction. There has also been greater caution in initiating opioid therapy for treating chronic pain. In this study, researchers used linked administrative databases to identify a cohort of people with opioid use disorder in British Columbia, Canada then characterized initial opioid prescriptions among this cohort. There was a particular focus on the setting where the initial opioid prescription was received and the doses, durations, and prescribing of concomitant medications that went against current prescribing guidelines over time. Findings from this study could help identify points of intervention to prevent future cases of opioid use disorder.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study used a population-level linkage of 6 health administrative databases in British Columbia, Canada to define a cohort of individuals in the province with opioid use disorder from 1996 to 2018 then characterized initial prescriptions for non-cancer opioid analgesics among this cohort before the development of opioid use disorder.

The database used captured prescription medication dispensing, hospitalizations, physician billing records, deaths and their underlying causes, emergency department visits, and incarceration. An algorithm was used to identify individuals with opioid use disorder and these individuals were followed from their first health system contact to the first record of opioid use disorder.

Individuals with a diagnosis of cancer or receiving palliative care were excluded, and initial opioid prescriptions from 2001 to 2018 were included in the analysis to allow for 5 years of data capture to establish identification of opioid use disorder. This cohort of individuals with opioid use disorder has been used in previous studies. There were 3 main analyses conducted in this study:

- Among the defined cohort of individuals with opioid use disorder, those with a history of opioid prescribing before developing the disorder were compared to those without a history of opioid prescribing based on demographics and clinical characteristics.

- Among individuals with opioid use disorder who received an opioid prescription before they developed the disorder, that initial prescription was characterized based on dose and duration of the prescription, setting of where prescription originated from, and guideline non-concordance. The setting where the prescription originated was defined as: post-inpatient (e.g., after a surgical procedure), non-inpatient acute (e.g., after an emergency department visit), or non-acute (e.g., after a primary care visit). Guideline non-concordance was defined as either a prescription of 90 or more morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day (“high-dose prescription), a prescription consisting of pills to last 7 days or longer (“long-duration prescription), or a 1 day or more overlap with a sedative prescription (“concomitant opioid and sedative prescription”; e.g., benzodiazepine). This analysis was also stratified by 3 time periods to assess change over time: 2001-2006, 2007-2012, and 2013-2018.

- Researchers predicted the probability of each type of guideline inconsistency by prescription setting and stratified by the 3 defined time periods while controlling for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that might affect this relationship.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Exposure to an opioid prescription among individuals identified with opioid use disorder increased over time.

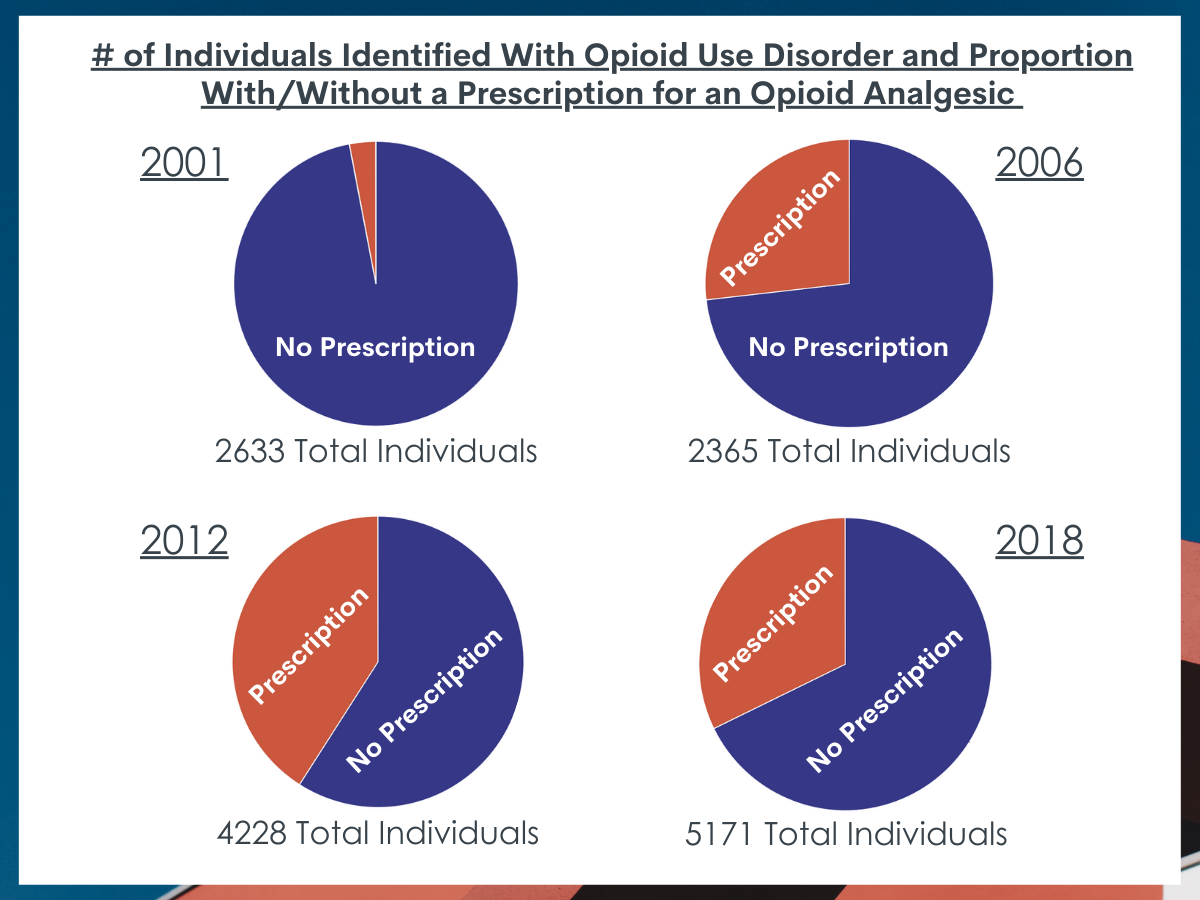

Of the 66,372 individuals identified as having opioid use disorder from 2001 to 2018, 21,331 (32.1%) had received an opioid prescription prior to identification. This proportion increased over time, representing 3% of the cohort in 2001 and peaking at 41% of the cohort in 2011 before slightly decreasing to 32% of the cohort in 2018. Compared to individuals identified with opioid use disorder who did not have a history of opioid prescribing prior to identification, individuals with a history of opioid prescribing were older and more likely to have comorbid conditions, such as alcohol use disorder, another drug use disorder, or a mental health condition.

Risky initial opioid prescriptions among individuals identified with opioid use disorder differed by guideline non-concordance and changed over time.

The median daily dose was 41.2 MME and the median number of days prescribed was 7 days in the first time period (2001-2006) and these slightly declined over the next 2 time periods (2007-2012 and 2013-2018). “Long-duration prescription” (53%) was the most common guideline non-concordance in the first time period followed by “concomitant opioid and sedative prescription” (17%) and “high-dose prescription” (16%). “High-dose prescription” non-concordance remained relatively stable over time while “long-duration prescription” dropped 9 percentage points and “concomitant opioid and sedative prescription” dropped 6 percentage points over the subsequent 2 time periods. Non-acute settings (48%), such as primary care, were the most prevalent setting where an opioid prescription originated in the first time period followed by non-inpatient acute (33%), such as the emergency department, and post-inpatient (19%) settings, such as after a surgical procedure. The proportion of prescriptions from non-inpatient acute settings changed little over time while the proportion for non-acute settings decreased 4 percentage points and the proportion for post-inpatient settings increased 6 percentage points over the subsequent 2 time periods.

The probability of receiving a guideline non-concordant initial opioid prescription differed by setting and time period.

The probability of receiving a “high-dose prescription” stayed relatively consistent over time across all settings, ranging from 10-22%. The probability of receiving a “long-duration prescription” decreased over time in non-acute and post-inpatient settings while staying relatively consistent in non-inpatient acute settings, ranging from 30-60% in all 3 settings across the 3 time periods. The probability of “concomitant opioid and sedative prescription” was the lowest among the non-concordance measures, ranging from 10-20% and decreasing across time periods for each setting.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found that around one-third of individuals identified as having an opioid use disorder in British Columbia, Canada from 2001 to 2018 had received an opioid prescription prior to identification, with this proportion increasing significantly over time. Oftentimes, these individuals received initial opioid prescriptions that were not consistent with current prescribing guidelines although this decreased over time.

There is consensus that increases in opioid prescribing have overexposed the population to opioids and played a substantial role in creating the opioid crisis in North America. This is especially true in the United States where total prescription opioid consumption has been higher than any other developed nation since the 1990’s. Prescription opioid use disorder can develop from 2 primary pathways: legitimate medical use and non-medical use.

Among people on long-term opioid therapy (using prescription opioids on a regular basis), it is estimated that between 8% to 12% are likely to have an opioid use disorder. The overprescribing in the population of opioids also has the unintended consequence of increasing non-medical use through left over opioid medications that were never used by the intended patient subsequently being used by someone else. It is estimated that between 75-80% of heroin users began using prescription opioids prior to heroin use, mostly through non-medical use.

Findings from this study highlight a potential role of legitimate prescription opioids in nearly one-third of the cases of opioid use disorder identified in this study. However, this study was not designed to assess the causal role of prescription opioids in the development of opioid use disorder as the entire cohort used in this study had opioid use disorder. In other words, this study did not have a comparison group of individuals exposed to prescription opioids who did not develop opioid use disorder, which would be necessary to assess this relationship.

Exposure to prescription opioids is common, especially in the United States, as 1 study in Massachusetts found that 57% of the adult population had received an opioid prescription from 2011-2015. In addition, this study only characterized initial opioid prescriptions and it is not clear if these individuals received only 1 prescription (i.e., were briefly opioid-exposed) or continued prescription opioid use (i.e., initiated long-term opioid therapy). The latter would put individuals more at risk of developing opioid use disorder.

The most common type of guideline inconsistency was for long-duration opioid prescriptions, with around half of initial prescriptions meeting this criterion. This is an important discovery given that longer duration exposure has been found to be a stronger risk factor for developing opioid use disorder than short term higher dose administration, and these risks related to opioid prescribing are more influential than individual-level factors in developing opioid use disorder. Even in the latter time period (2013-2018), 44% of initial opioid prescriptions for individuals who subsequently developed opioid use disorder were for 7 days or more, suggesting room for improvement. In the United States, it was found that an initial opioid prescription written for only 10 days was associated with a 20% probability of continued opioid use 1 year later. Many states have passed restrictions on the number of days that an initial opioid prescription can be written for.

This study found that the most common setting where an initial opioid prescription originated was from a non-acute setting, such as primary care. This is significant because primary care physicians have ongoing relationships with their patients whereas the post-inpatient setting and the non-inpatient acute setting are likely markers for prescription opioids received after surgery and in the emergency department, respectively. There is some evidence that prescription opioids may be effective for some forms of acute pain but limited evidence that they are effective for chronic non-cancer pain. Therefore, this is a concerning finding given that an initial opioid prescription from a non-acute setting (e.g., in primary care) is more likely to be a repeated prescription of longer duration and may represent initiation of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain.

The study found that guideline non-concordance decreased over time in all 3 medical settings. This is a promising finding highlighting the potential impact of policies and interventions to improve guideline concordance. This decrease began to happen in the second time period (2007-2012), before new guidelines were issued from the United States (2016) and Canada (2017) promoting more cautious opioid prescribing, suggesting that other programs and policies in British Columbia may have contributed to improved guideline concordance. This warrants further research.

There is a contentious debate around the role of policies and initiatives to reduce opioid prescribing when research has shown that these interventions may increase switching from licit to illicit opioids. In other words, if prescribed supply is lowered, people will turn to the illegal market to obtain opioids. This is especially relevant given the proliferation of fentanyl in the illicit opioid supply. However, policies to address opioid prescribing are needed to reduce new cases of opioid use disorder and may be more straightforward to implement and scale than policies addressing the illicit opioid supply. In fact, these types of polices have been shown to save lives in long-term simulations. A portfolio of policies is needed to address the opioid crisis in North America, including those to promote more cautious opioid prescribing and those to address the increasingly dangerous illicit opioid supply. Another emerging intervention in Canada worth studying is providing an “off-label” prescription of opioid analgesics to individuals with opioid use disorder to ensure a safe supply.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This study was not designed for estimating the causal relationship between exposure to a prescription opioid and the development of opioid use disorder.

- Historically, opioid prescribing has been much different in the United States compared with Canada. In addition, the healthcare systems of these 2 countries are very different. Therefore, generalizing these results to the United States or other countries should be done with caution.

- This study only characterizes the initial opioid prescription before a person is identified with opioid use disorder. Thus, we do not know if these individuals were maintained on prescription opioids for months or years or doses were escalated over time, both risk factors for developing opioid use disorder.

- The data used in this study to identify a cohort of people with opioid use disorder in British Columbia is from 1996 to 2018. It is possible that some of these individuals developed opioid use disorder or received prescription opioid therapy prior to 1996.

- Settings where prescriptions originated were not known with certainty due to some databases having years of missing data and misclassification error. For example, dental visits were not captured by the linked databases although this is commonly a setting where opioids are prescribed.

BOTTOM LINE

Several linked databases identified individuals with opioid use disorder in British Columbia, Canada, from 2001 to 2018 and found that around one-third of these individuals received an opioid prescription prior to identification, with this proportion increasing significantly over time. Oftentimes, these individuals received initial opioid prescriptions in non-acute settings, such as a primary care setting, and the prescriptions were not concordant with current prescribing guidelines, although this decreased over time.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Opioid exposure through a prescription is a risk factor for developing opioid use disorder, including high-dose prescriptions (50 MME/day or more) and more importantly, long-duration prescriptions (7 days or more). Co-prescription of opioids with sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, increases the risk of overdose-related mortality. Opioids may be effective for severe acute pain, such as after surgery or in the emergency department, if only taken for a few days but the risks likely outweigh the benefits for using opioids for non-cancer chronic pain. Individuals with prior history of substance use disorder are increasingly at risk for developing opioid use disorder and other adverse outcomes from opioid therapy. Extreme caution should also be taken for initiating opioid therapy in an individual with a history of an opioid use disorder.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: There is consensus that increases in opioid prescribing have overexposed the population to opioids and played a substantial role in creating the opioid crisis in North America. Opioid exposure through a prescription is a risk factor for developing opioid use disorder, including high-dose prescriptions (50 MME/day or more) and especially long-duration prescriptions (7 days or more). Co-prescription of opioids with sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, increases the risk of overdose-related mortality. Opioids may be effective for severe acute pain, such as after surgery or in the emergency department, if only taken for a few days but the risks likely outweigh the benefits for using opioids long-term for non-cancer chronic pain. Individuals with prior history of substance use disorder are increasingly at risk for developing opioid use disorder and other adverse outcomes from opioid therapy. Extreme caution should also be taken for initiating opioid therapy in an individual with a history of an opioid use disorder.

- For scientists: This study used a population-based linkage of multiple databases to characterize initial opioid prescriptions among an identified cohort of individuals with opioid use disorder. However, the design of this study did not assess the causal relationship between an initial opioid prescription and subsequent development of opioid use disorder. Also, the study only characterized the initial prescription and did not examine if opioid therapy was limited to this 1 prescription or was continued (e.g., initiation of long-term opioid therapy). Future studies could be designed to measure the incidence of opioid use disorder after an initial opioid prescription as well as how the risk of opioid use disorder changes based on dosage and duration of opioid therapy. Guideline non-concordance decreased over time, before national guidelines promoted more cautious opioid prescribing, warranting further exploration.

- For policy makers: There is consensus that increases in opioid prescribing have overexposed the population to potent and seductive opioids and played a substantial role in creating the opioid crisis in North America. Individuals develop opioid use disorder from both medical and non-medical use. Reducing opioid prescribing and decreasing dosage and duration of opioid therapy, such as those espoused in newer national guidelines, are a promising strategy although there are some unintended consequences to policies that reduce opioid prescribing, such as some individuals with opioid use disorder transitioning from a licit to an illicit opioid supply. A multipronged array of policies that adequately address opioid supply as well as the continuum of care (prevention, harm reduction, treatment, and recovery) is needed to address the opioid crisis.

CITATIONS

Enns, B., Krebs, E., Thomson, T., Dale, L.M., Min, J.E., Nosyk, B. (2021). Opioid analgesic prescribing for opioid-naïve individuals prior to identification of opioid use disorder in British Columbia, Canada. Addiction, 116(12), 3422-3432. doi: 10.1111/add.15515