Reachable moments: Engaging people in substance use disorder treatment during medical hospitalizations

Every day, tens of thousands of people are admitted to United States hospitals for medical problems related to substance use disorder, yet typically hospitals don’t attempt to engage these individuals in addiction treatment. This represents a massive missed opportunity which a handful of pilot programs, like the one evaluated in this study, are seeking to address.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Although individuals with substance use disorder have more frequent hospitalizations and higher healthcare costs compared to the general population, most hospitalized patients with substance use disorder are not engaged in care prior to hospitalization, and one in seven patients in general hospitals have a substance use disorder. Further, most hospitals do not address substance use disorder during acute inpatient encounters. Failure to treat substance use disorder in hospitals leads to unaddressed withdrawal symptoms, failure to complete recommended medical treatment, and high rates of discharge against medical advice. Moreover it represents a major missed opportunity to connect individuals to substance use disorder treatment who otherwise may not present for care. This study assessed outcomes for individuals engaging in a new program in Oregon called Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT), that includes care from addiction medicine physicians, social workers, and peers with lived experience in recovery to identify and begin substance use disorder treatment for individuals hospitalized for addiction-related medical problems.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a cohort study utilizing Oregon Medicaid claims data to compare individuals receiving the IMPACT intervention and matched controls. Participants were 18-64-year-old Oregon Medicaid beneficiaries with substance use disorder, hospitalized at an Oregon hospital between July 1, 2015, and September 30, 2016. To ensure demographic and clinical similarity among the compared groups of hospital patients who received and did not receive the IMPACT services, IMPACT patients (n= 208) were matched to controls (n= 416) using a propensity score that accounted for substance use disorder, gender, age, race, residence region, and diagnoses. In other words, for each IMPACT participant, a similar control participant was identified from the Oregon Medicaid claims dataset.

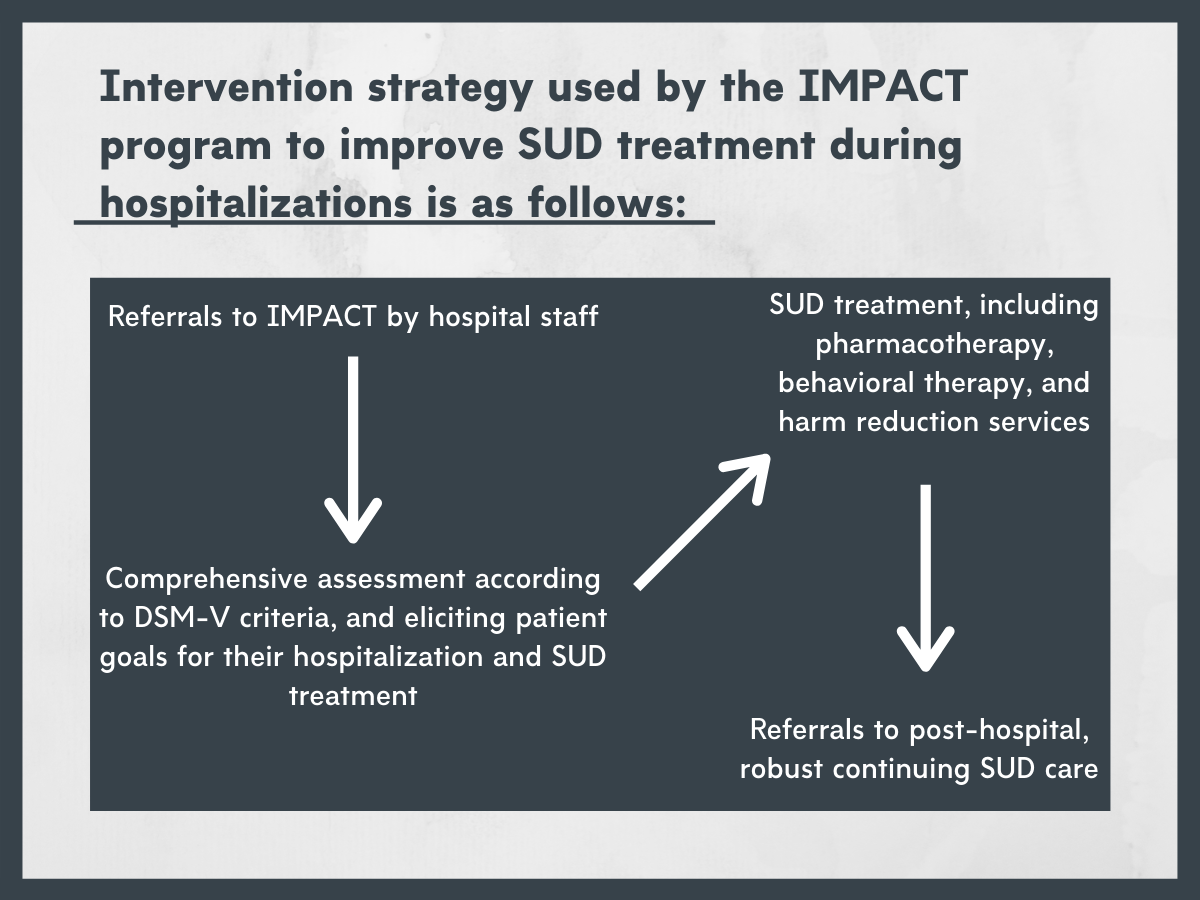

What happens in the IMPACT program?

Inpatient medical and surgical providers and hospital social workers refer patients with known or suspected substance use disorder to IMPACT. IMPACT is open to patients with any substance use disorder, regardless of whether they are ready to change their substance use or not or have any interest in treatment. IMPACT medical providers and social workers perform an initial comprehensive assessment, including DSM-5 substance use disorder diagnosis assessment, and eliciting of patient goals around the acute hospitalization and substance use disorder. They then initiate various kinds of substance use disorder treatments, including pharmacotherapy and behavioral treatments, while also offering harm reduction services, depending on the patient’s willingness to engage with different approaches. IMPACT includes robust referral pathways to post-hospital substance use disorder care and, in some cases, forges relationships with rural substance use disorder providers to coordinate post-hospital care.

Figure 1.

Outcomes assessed.

Outcome data were obtained from the Oregon Medicaid claims database that included physical and behavioral health and pharmacy claims in calendar years 2015-2016. The primary study outcome was post-discharge substance use disorder treatment engagement, which included two or more of the following occurring on at least two separate days within 34 days of hospital discharge: 1) A filled prescription for a substance use disorder medication (e.g., buprenorphine), 2) engagement in substance use disorder treatment demonstrated by the presence of a procedure code (e.g., methadone administration at an opioid treatment program, behavioral treatment for stimulant use disorder, etc.), or 3) a clinic visit with an substance use disorder diagnostic billing code.

In their analysis, to try and isolate the difference between receiving versus not receiving IMPACT on treatment engagement, the authors statistically accounted for individual factors that might explain treatment engagement, including substance use disorder type (opioid substance use disorder vs. non-opioid substance use disorder), gender, age, race/ethnicity, Portland tri-county area residence as a surrogate marker for urban versus non-urban healthcare systems, Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group category, and Chronic Illness & Disability Payment System risk score.

Experimental group.

During the study window, there were 357 referrals to the IMPACT program. 269 (75.3%) referrals had Oregon Medicaid, with 264 were eligible for IMPACT and 208 ultimately seen by IMPACT. 17.8% of experimental group participants had previous substance use disorder treatment.

Control group.

The study authors used propensity score matching to identify a control group from the Oregon Medicaid claims database. This is a sophisticated statistical approach that ensures that the experimental and control groups are similar on a range of individual factors, thus increasing confidence that any between-group outcome differences are a result of the IMPACT intervention and not simply differences in other factors that might vary between the two groups.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

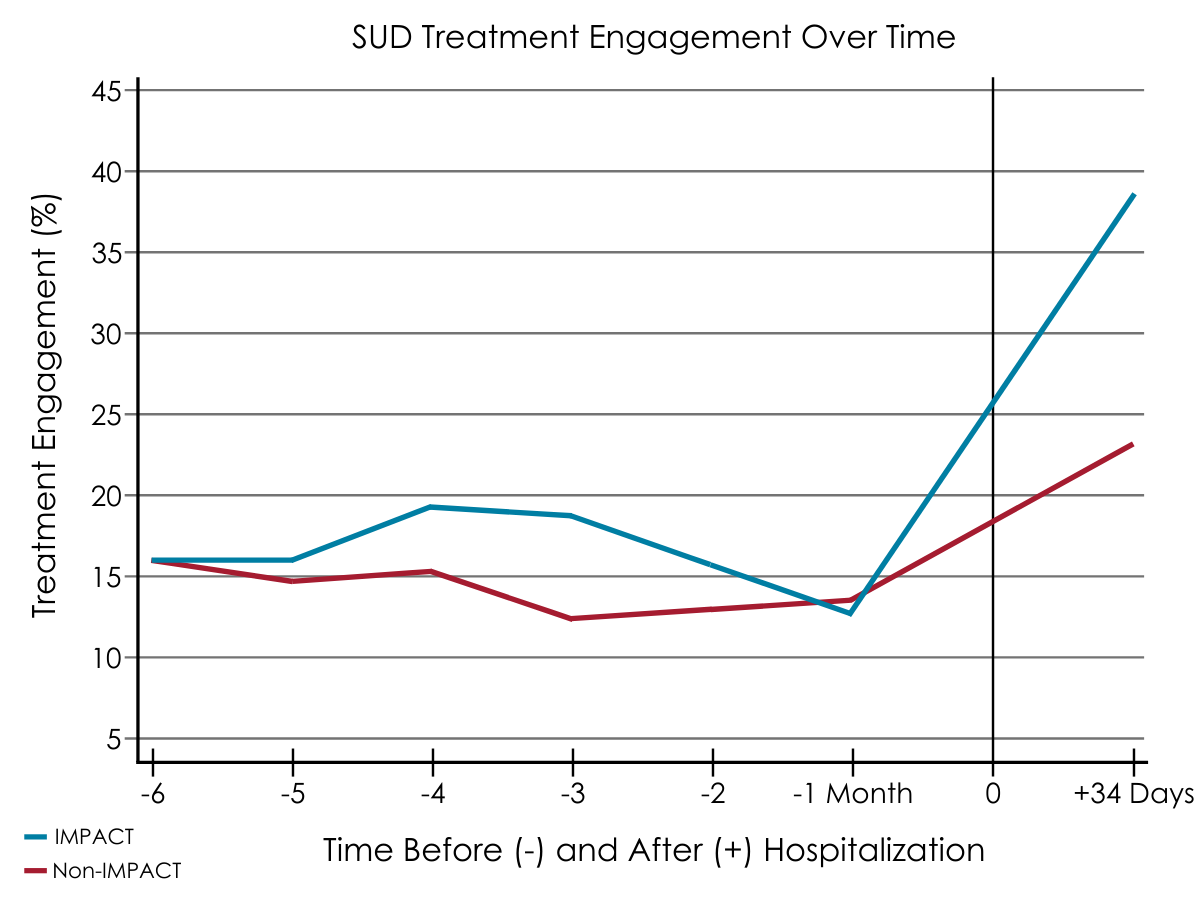

The authors found that IMPACT patients were twice as likely to engage in substance use disorder treatment following discharge compared to controls (38.9% vs. 23.3%). As expected, those engaged in treatment before admission had substantially greater odds of receiving treatment after discharge. The authors sought to check if this factor might have been influencing results. When they re-ran the analysis excluding all participants who had previously had substance use disorder treatment, they found similar results, suggesting previous substance use disorder treatment was not influencing this finding. They also found that patients with opioid use disorder were 83% more likely than those without an opioid use disorder to engage in treatment. It is especially important to mention, at 34 days, 1 person in IMPACT and 14 people in the control group had died.

Figure 2.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

These findings provide robust evidence supporting the potential of hospital-based substance use disorder interventions, and build on previous work that found that patients who received inpatient addiction medicine consultation were more likely to report substance use disorder treatment engagement at 30 and 90 days after discharge compared to those who did not.

Findings also suggest patients with opioid use disorder had greater odds of engagement than those with non-opioid substance use disorder. The authors speculate that this may be due to greater uptake and effectiveness of medications for opioid use disorder compared with non-opioid substance use disorder, for which medications are typically less available and/or effective.

Critically, the authors observed one death in the IMPACT program versus 14 controls. This difference is striking, even though the control group was twice as large. It is possible that the fewer observed deaths in the IMPACT group were related to patients receiving Suboxone prescriptions, which can reduce opioid use and protect against overdose, although it is not clear if the observed deaths were overdose related. More research is needed to more deeply explore this observed difference.

The overall importance of these findings may have high clinical and public health significance. The IMPACT program bears many similarities to the Addiction Consult Team program at Massachusetts General Hospital, which has also been shown to increase substance use disorder treatment engagement. These results also converge with previous findings that addressing substance use disorder in primary care settings leads to fewer days of inpatient care, fewer emergency department visits, and greater engagement in primary care. These studies collectively speak to the value and potential of screening and assessing for, as well as addressing, substance use disorder in medical settings even when the hospital admission appears unrelated to substance use.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The IMPACT program in Oregon and Addiction Consult Team at Massachusetts General Hospital are promising examples of the potential of these kinds of medical setting based interventions. At the same time, these programs were implemented at major medical and academic centers with many resources. Whether a hospital can carry out this type of thing with fewer resources is not yet known, and is an important question that needs to be addressed.

- The Oregon Medicaid claims database is primarily maintained for billing and may not accurately reflect all participant diagnoses.

- Claims do not include non-billable substance use disorder services such as 12-step meetings, syringe exchange services, or prescriptions dispensed on the day of discharge from a hospital pharmacy – a common practice for IMPACT that potentially underestimates its effect. Results may therefore underestimate treatment engagement following hospital discharge.

- Relatedly, Medicaid claims data do not reliably include important social factors such as housing and transportation, which are known to strongly influence treatment engagement.

- The study was not a randomized controlled trial, and thus may be influenced by selection bias. For example, it is possible that providers referred patients who would be more or less likely than controls to engage in substance use disorder treatment.

- This study was performed in a single state with low racial and ethnic diversity and was among the first states to expand Medicaid, which may limit generalizability of its findings.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The results in this paper suggest the potential value of hospital-based substance use disorder interventions, and build on previous work suggesting that patients receiving substance use disorder consultation during hospitalizations may be more likely to engage in substance use disorder treatment following discharge. This new treatment engagement model is being taken up by a number of hospitals and healthcare systems in the United States, but the vast majority of hospitals lack such programs, and are therefore unlikely to offer a substance use disorder consultation for individuals hospitalized with addiction-related medical problems. Nevertheless, hospital admissions offer an excellent opportunity to connect with providers and potentially connect to substance use disorder care.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: The results in this paper suggest the potential value of hospital-based substance use disorder interventions, and build on previous work suggesting that patients receiving substance use disorder consultation during hospitalizations may be more likely to engage in substance use disorder treatment following discharge. This new treatment engagement model is being taken up by a number of hospitals and healthcare systems in the United States, but the vast majority of hospitals lack such programs. It is likely that such programs, even in primary care settings, have the capacity to improve patient care and reduce costs through readmissions for healthcare systems.

- For scientists: The results in this paper suggest the potential of hospital-based substance use disorder interventions, and build on previous work suggesting that patients receiving substance use disorder consultation during hospitalizations may be more likely to engage in substance use disorder treatment following discharge. Replication of this work is needed across a range of hospital and healthcare system settings. More research is also needed that explores substance use outcomes of such programs and utilizes longer follow-up periods to explore if such interventions have sustained effects. Additionally, longitudinal, prospective, randomized controlled trials will allow for more confident causal inferences to be made regarding the effects of IMPACT or similar initiatives.

- For policy makers: The results in this paper suggests the potential value of hospital-based substance use disorder interventions, and build on previous work suggesting that patients receiving substance use disorder consultation during hospitalizations may be more likely to engage in substance use disorder treatment following discharge. This new treatment engagement model is being taken up by a number of hospitals and healthcare systems in the United States, but the vast majority of hospitals lack such programs. It is likely that such programs, even in primary care settings, have the capacity to improve patient care and reduce costs through readmissions for healthcare systems. Supporting the development of such programs may ultimately reduce healthcare costs.

CITATIONS

Englander, H., Dobbertin, K., Lind, B. K., Nicolaidis, C., Graven, P., Dorfman, C., & Korthius, P. T. (2019). Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: A propensity-matched analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, (Epub). doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05251-9