Do kids receive medication for opioid use disorder?

Buprenorphine and naltrexone are life-saving treatments for individuals with opioid use disorder that can help prevent overdose and increase remission rates, but do some adolescents have greater access than others? This study reviewed insurance records to answer the question:

"Do some adolescents have greater access than others?"

They found some stark inequalities….

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Between 1992 and 2012, the prevalence of opioid misuse and opioid use disorder doubled among adolescents, with some recent decline since then. Buprenorphine (a partial opioid agonist) and naltrexone (an opioid antagonist) are FDA approved life-saving treatments for opioid use disorder that can prevent lethal overdose and reduce injection drug use. The effectiveness of opioid agonist and antagonist therapies has been well investigated among adults but is less studied among youth.

Further, the extent that various youth with opioid use disorder have equal access to pharmacotherapies along lines of age, gender, race-ethnicity, and other factors is unclear and could have the potential to create health disparities (i.e., group differences in health). Recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report suggests that early intervention in the trajectory youth addiction is important for preventing more severe disease and consequences and downstream. This study aimed to fill the knowledge gap regarding the extent of buprenorphine and naltrexone receipt among adolescents treated for opioid use disorder in the US and see if receipt of these medications varies by socio-demographic characteristics.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study reviewed claims from a large US commercial health insurer with members in every state who all had prescription drug coverage. The sample included youth aged 13 to 25 years who received a diagnosis of opioid use disorder between the years 2001 – 2014 with 6 months or more of continuous enrollment following the first date of diagnosis. Diagnosis receipt was defined by enrollees who had an opioid use disorder claim filed as primary or secondary. Primary outcome was receipt of buprenorphine (buprenorphine or buprenorphine naloxone combination) or naltrexone (in its oral short-acting or intramuscular extended-release formulation) within 6 months of the first observed opioid use disorder diagnosis. Other variables in the model included sex, age at diagnosis, race-ethnicity, geographic region (i.e., metropolitan vs nonmetropolitan), neighborhood educational level, and neighborhood poverty level.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

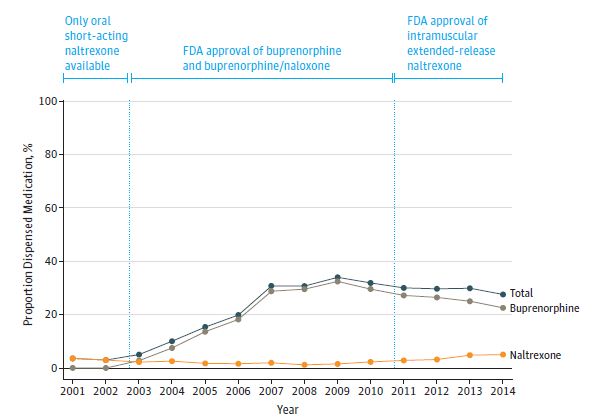

Over the course of 14 years, 5,580 of 20,822 youth (1 in 4, or 25%) with opioid use disorder received either buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months. The year 2002 had the lowest percent of youth receiving either medication (3%). From 2002 to 2009 medication receipt increased by more than 10 times culminating in 31.8% of youth with an opioid use disorder diagnoses receiving buprenorphine or naltrexone (see Figure).

Younger adolescents were less likely to receive buprenorphine or naltrexone than older youth. Specifically, compared to youth ages 21-25 youth ages 13-15 were 99.97% less likely to receive pharmacotherapy, ages 16-17 were 75% less likely, and ages 18-20 were 36% less likely. Females were 21% less likely to receive either medication compared to males. Blacks were 42% less likely and Hispanics 17% less likely to receive either medication compared to Whites although these race differences disappeared by 12 months. Overall, buprenorphine was dispensed 8 times more often than naltrexone. Naltrexone was more commonly dispensed to younger individuals ages 16-17 (18.7%) compared to older individuals ages 21-25 (9.7%), females (12.2%) compared to males (10.3%), youth in metropolitan areas (12.0%) compared to non-metropolitan areas (8.6%), higher educational level neighborhoods (12.3%) compared to lower (6.9%), and neighborhoods with less poverty (12.3%) compared to high poverty (7.2%).

Proportion of Youth Dispensed Buprenorphine or Naltrexone within 6 Months of Opioid Use Disorder Diagnosis

WHY IS THIS STUDY IMPORTANT

Opioid use disorder is a potentially lethal health condition that can be chronic for some. The availability of opioid agonist and antagonist treatments has changed the trajectory of the disorder resulting in fewer deaths, HIV infections, less drug use, as well as increased remission rates and improved quality of life. Understanding which youth are more likely to receive pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder, which medicine they are likely to receive, and how pharmacotherapy dispensing varies by sociodemographic characteristics is therefore necessary to inform the expansion of opioid use disorder treatment services in the US.

This study showed that most youth with opioid use disorder do not receive medication within 6 months, further, from 2009 onward there was an overall decrease in the percent of youth receiving pharmacotherapy during an escalation in the opioid use disorder diagnosis rate. This decrease in prescribing affected certain sociodemographic groups more than others, in particular, those who were younger, female, Black or Hispanic. Individuals under the age of 16 were least likely to receive medications which may reflect that buprenorphine is only FDA approved for individuals 16 years of age or older. Females, Blacks, and Hispanics were also less likely to receive medications which could reflect differences in clinician biases, patient severity, or patient preferences regarding the use of medication in treatment.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The receipt of methadone (opioid agonist therapy) was not assessed in this study which could yield an underestimation of the number of youth receiving pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder in this sample.

- Opioid use disorder severity was not assessed in this study and could help explain why older youth or other socio-demographic groups were more likely to receive pharmacotherapy

NEXT STEPS

Future research should identify what percentage of adults over the age of 25 with an opioid use disorder-related insurance claim received medication and compare it to the population of individuals with an untreated opioid use disorder. Additional research should also identify the barriers that restrict access to medications for youth with opioid use disorder and identify for whom opioid agonist therapies may be contraindicated.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals & families seeking recovery: This study of one US commercial health insurer found that only 1 in 4 youth diagnosed with opioid use disorder received buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months. Additionally, the likelihood of receipt was even lower among younger adolescents, females, Blacks, and Hispanics. Opioid agonist treatments can prevent cravings, mitigate withdrawal symptoms, and block the effects of other opioid drugs; however, this study showed that receipt is disproportionately restricted in the US. If you (or someone you know) are struggling with opioid use disorder, be persistent in learning all your treatment options including medications.

- For scientists: This study identified that only 1 in 4 commercially insured youth with opioid use disorder diagnoses received pharmacotherapy, and disparities based on female gender, younger age, and Black or Hispanic race-ethnicity were observed. Policies, attitudes, and messages that serve to prevent patients from accessing a medication that can effectively treat a potentially life-threatening condition may be harmful to adolescent health. Additional research should focus on identifying patient/parent preferences and attitudes as moderators of medication use as well as any contraindications for adolescents’ use of opioid agonist (and partial agonist) and antagonist therapies and identify the barriers to accessing pharmacological treatment.

- For policy makers: This study shows that youth with commercial insurance often do not receive pharmacotherapy to treat opioid use disorder, and younger adolescents, females, Blacks, and Hispanics are even less likely. The American Academy of Pediatrics advocates for increasing resources to improve access to opioid agonist, partial agonist, and antagonist treatments for adolescents and young adults with an opioid use disorder. Regulatory changes and expansions of Medicaid coverage for pharmacological treatment could improve access to evidence based treatments.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study revealed an important treatment gap by finding that only a portion of youth with opioid use disorder diagnosis received pharmacotherapy, and younger adolescents, females, Blacks and Hispanics were even less likely. This finding informs the recent policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics calling for expanded access to medications for youth with opioid use disorder by implementing pharmacotherapy in pediatric primary care. Specialty practices can also help fill this treatment gap by retaining pediatric specialists on staff

CITATIONS

Hadland, S.E., Wharam, J.F., Schuster, M.A., Zhang, F., Samet, J.H., & Larochelle, M.R. (2017). Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescent and young adults, 2001-2014. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(8), 747-755.