What are the barriers to starting and maintaining a program of medication treatment in healthcare settings?

Opioid use disorder (OUD) medications are effective life-saving treatments that help support recovery. However, only about one-third of addiction treatment organizations offer any medication for OUD treatment. This study assessed barriers to newly implementing and delivering medication treatment, including practical barriers as well as negative attitudes and stigma toward medication treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Opioid use disorder (OUD) medications (e.g., agonists like methadone and buprenorphine, as well as antagonists like naltrexone) are effective lifesaving therapies that promote successful treatment, enhance recovery outcomes, and reduce morbidity and mortality. Despite their demonstrated benefits, recent national data suggest that only about 33-36% of outpatient and 40% of residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs offer any OUD medication treatment. In the past, commonly reported barriers to implementing medication treatment have included those pertaining to regulations, funding, and infrastructure. It is essential to understand what barriers to delivery and use of medications persist and why, as doing so will ultimately help us increase the availability and adoption of these lifesaving medications by treatment staff and patients to better address the opioid crisis.

Though several potential barriers have been studied to date, they primarily concern the structural obstacles to medication treatment. One factor that might pose an additional barrier to medication uptake that has yet to be thoroughly assessed is the medication attitudes of treatment personnel within healthcare systems.

Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services passed a new policy in 2018, offering a unique opportunity to assess the role of healthcare system attitudes and other barriers on the adoption of medication treatment, and to inform national policies that reduce various barriers. More specifically, this law requires that OUD medication treatment be provided in all residential treatment programs by January of 2020 and outlines new regulations that aim to alleviate barriers related to insurance reimbursement, provide enhanced rates of medication treatment, and motivate prescribing through incentives, like offering providers payments based on their prescribing performance. The limited impact of these policies on expanding the provision/use of medication mirrors the difficulties experienced nationally and offers an opportunity to identify additional barriers to establishing new medication treatment programs in healthcare systems.

The current study evaluated potential barriers to medication treatment in this context, including practical barriers and barriers that Philadelphia’s new policy does not address: negative attitudes or stigma toward medication treatment and the patients who are using them.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The investigators conducted qualitative interviews among the leaders of 25 treatment organizations in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Interviews were conducted after the city announced the new policy (mandating medication treatment) but prior to the policy being fully implemented (i.e., from December 2018 to June 2019). At the time of the interview, all participating organizations had either not yet implemented, or only recently adopted, medication treatment within their programs. Questions concerned organization leaders’ perspectives and experiences with a particular emphasis on barriers and attitudes toward OUD medication treatment. The researchers identified and coded themes among interview responses, which were ultimately assessed as the primary study outcomes.

Interview questions specifically addressed the organization’s treatment philosophy and client population, leadership attitudes toward medication treatment as a way to address the epidemic, organizational and service payment factors that might be needed to support or enhance medication treatment provision. Facilities that had not yet adopted medication treatment were asked how/if they had the capacity to implement medication treatment, and facilities that had already begun to implement medication treatment were asked about the ways in which this was accomplished and financed. Organizations that were not interested in providing medication treatment were also asked about their reasons for being disinterested. Interviews were transcribed and coded thematically by two researchers to ensure consistency and reliability of the interview themes identified.

A total of 20 executive- and 5 clinical- directors (e.g., medical director, chief medical officer) across 25 organizations were interviewed. Among the 25 organizations, 13 were adopting agonist medications (11 of the 13 were also adopting antagonist medication), 5 were adopting antagonist medication only, and 7 were not adopting any OUD medications. Organization leaders had an average age of 57 years, and primarily consisted of white (80%) men (60%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

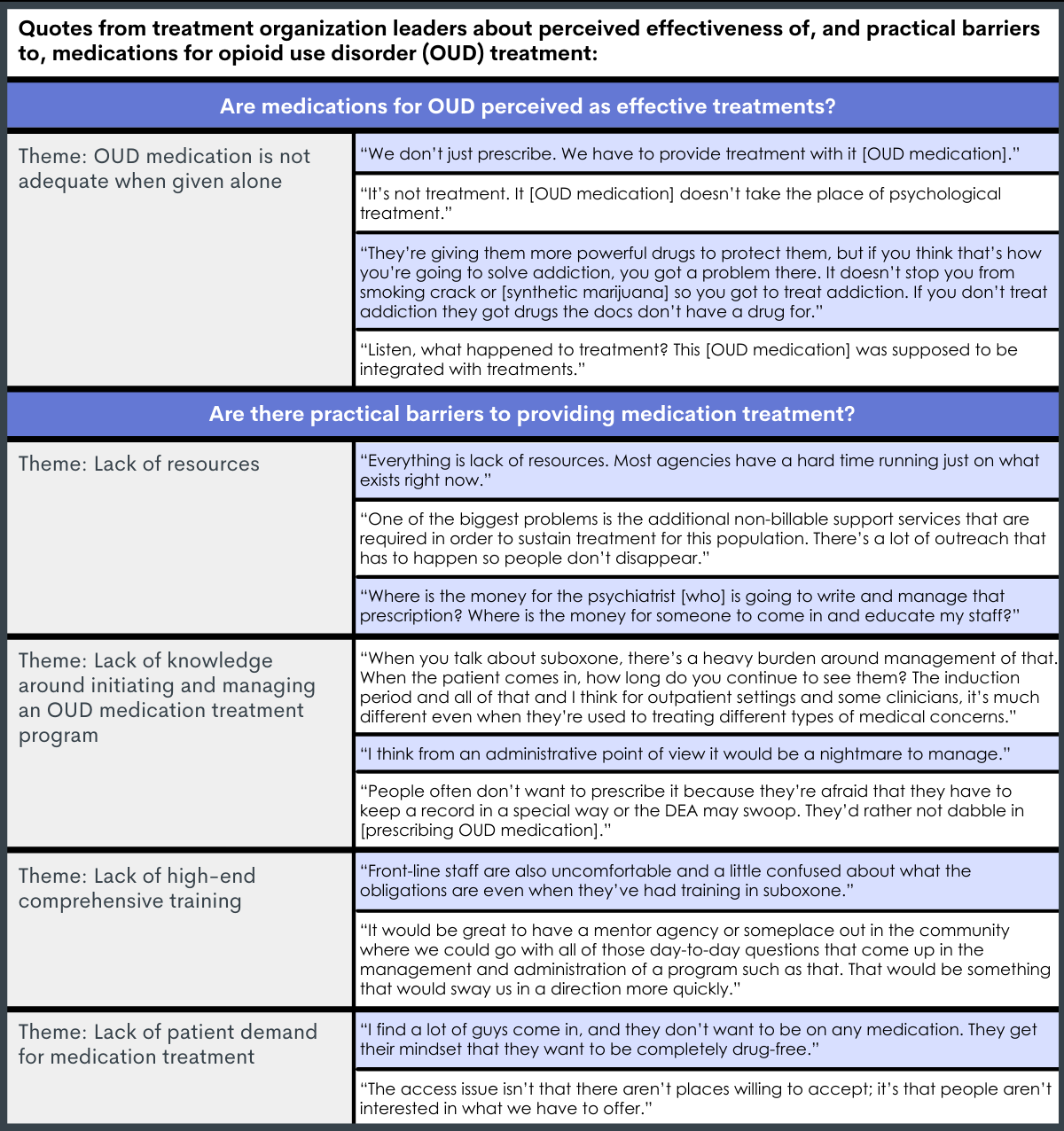

Organization leaders noted concerns that medication would replace psychosocial treatment and thought that a lack of resources and patient demand were barriers to providing medication treatment.

Organization leaders believed that medication treatment was not sufficient when given alone, and many were concerned that medication would replace, rather than supplement, psychosocial treatments. Across all organizations, leaders thought that a lack of financial (e.g., financial reimbursement restrictions for provider services) and educational (e.g., high-end mentored training, education around managing programs, patients, & federal regulation) resources also hindered their ability to start and maintain a medication treatment program. In addition, leaders reported that few patients wanted medication treatment, and this was an important barrier to providing it.

Figure 1.

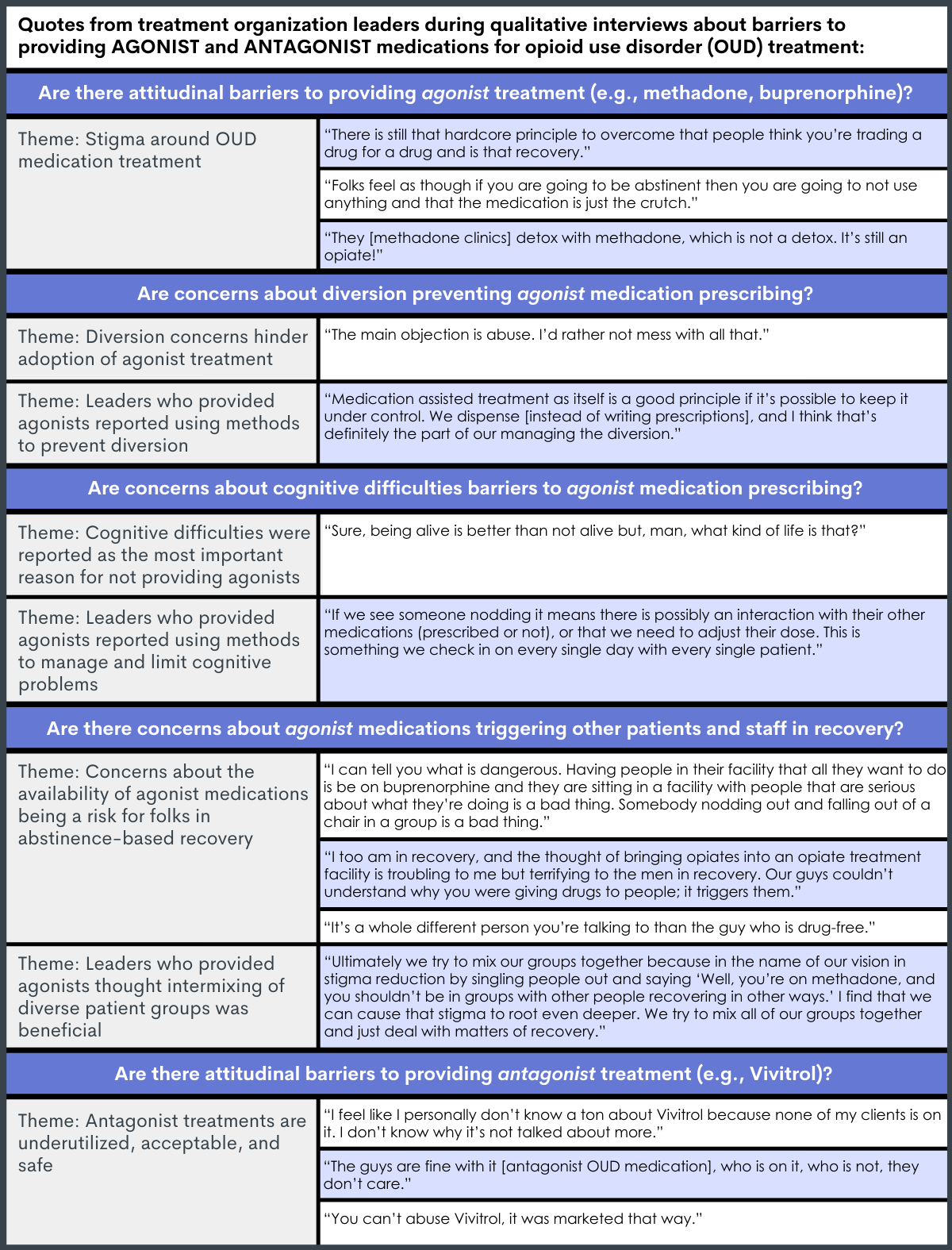

Leaders whose organizations had not yet adopted agonist medication treatments were more likely to hold negative beliefs about agonist medications and to report concerns around diversion, cognitive problems, and the effects that they might have on individuals seeking abstinence-based recovery.

Relative to leaders that had already implemented agonist treatment, leaders who had not were more likely to personally have negative attitudes toward agonists (e.g., medication just replaces one drug for another, inconsistent with abstinence-based recovery) and to have concerns that providing agonists could put staff and patients in abstinent-based recovery at risk of relapse. In addition, among non-agonist-adopting leaders:

- The most commonly reported barrier was worry about patients selling or diverting their agonist medication to other patients, staff, and the community.

- The most important barrier to providing agonists was concern about cognitive problems (e.g., agonist medications causing patients to ‘nod off’; attentional problems).

- Concerns that medication provision could put staff and patients in abstinent-based recovery at risk of relapse were also more likely.

In contrast, organizations that had already implemented agonist treatment:

- Reported methods they used to limit medication diversion (e.g., prescribing a limited amount of medication at a given time).

- Described dose-management practices to prevent cognitive difficulties.

- Reported purposeful mixing of medication treated and abstinent patients in an effort to reduce stigma, challenge preconceived notions about recovery, and encourage patients to learn from each other.

Leaders generally had fewer concerns about providing antagonist medications.

Organizational leaders mentioned themes around antagonist treatments being underutilized, safe, and acceptable among recovering peers and staff, with none of the leaders noting practical or ideological barriers to antagonist treatments like vivitrol.

Figure 2.

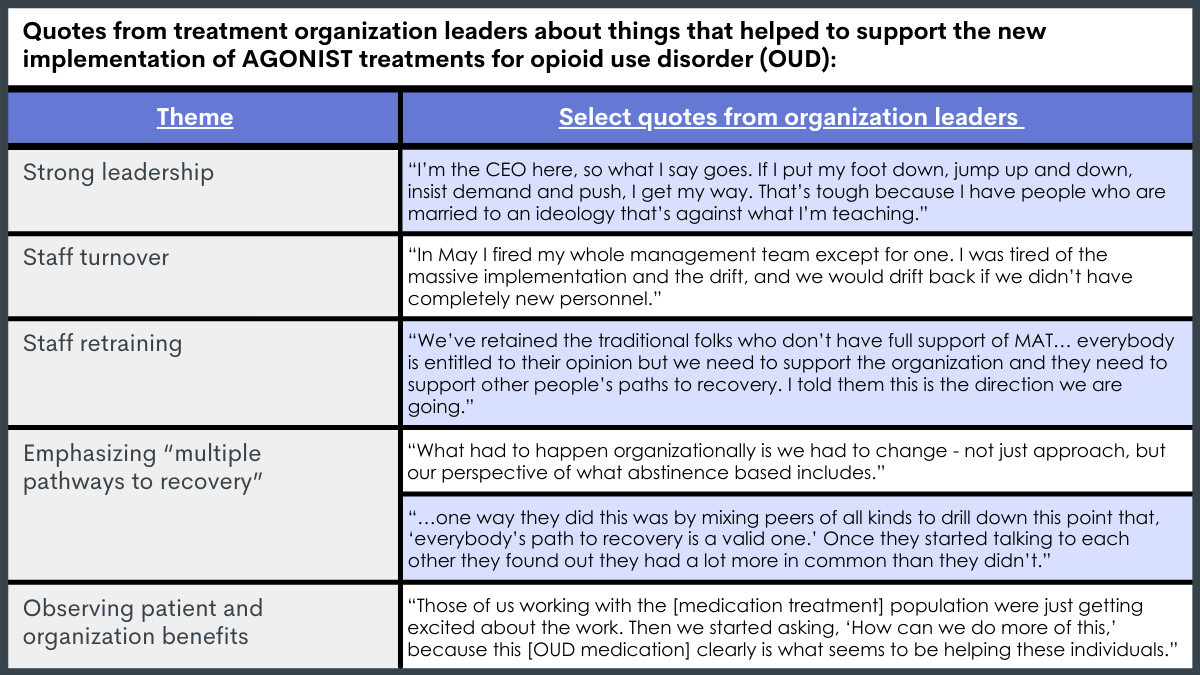

Organizations that newly implemented agonist-based medication treatment had 4 major themes that helped the implementation of such treatment programs.

Leaders in organizations that had started providing medication treatment within the past two years noted (1) the presence of strong leadership that advocate for medication treatment, (2) workforce turnover or re-training to foster organizational change and a unified medication philosophy, (3) redefining recovery throughout the organization to support multiple paths to recovery, and (4) observing patient improvements like enhanced retention and outcomes, in addition to financial benefits for the organization, as factors that helped support the new implementation of medication treatment.

Figure 3.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Findings here help us better understand what organizations may need in order to develop and maintain evidence-based programs that provide OUD medication treatment. Doing so will give insight to novel methods that further expand and support the provision of these lifesaving medications. This study also helped reveal misperceptions and stigma around medication among organization leaders, suggesting a need to educate and combat attitudes about medication, particularly agonists.

The majority of organization leaders did not perceive OUD medications as effective stand-alone treatments, with most suggesting that medication should be used as an add-on to psychosocial treatment. Though psychosocial treatment is effective for many individuals seeking recovery, studies generally suggest that psychosocial treatment provides no additional benefit when added to medication and medication management (e.g., comparable substance use outcomes). Accordingly, the American Society of Addiction Medicine recently revised their national practice guidelines to advise that psychosocial treatment should no longer be required during medication treatment. Rather, it is suggested that clinicians evaluate, offer, and refer patients to psychosocial treatment based on each patient’s individual needs, and that medication should be provided regardless of whether psychosocial treatment is available or accepted by the patient. Misperceptions about medication are important barriers to address, particularly since their perceived lack of effectiveness was common across all leaders, regardless of their organizations’ adoption of medication or not. Therefore, educating treatment personnel about new scientific evidence and ensuring up-to-date practices might ultimately help change attitudes and enhance comfort providing medication.

Leaders also reported many practical barriers to starting and maintaining a program of medication treatment, including a lack of resources (e.g., educational, financial), knowledge, and patient demand. Dedicating public funds to enhance resources for implementing medication treatment can ultimately help support programmatic start-up, including funds for additional clinicians and staff to support outreach, prescribing, and patient retention, as well as high-end continuing education for staff. Better training programs are also needed to ensure organizations have comprehensive guidance around starting up a medication treatment program and maintaining it from a patient and administrative perspective, and to ensure staff are knowledgeable about the benefits/risks of treatment to support accurate dissemination of information to patients.

Although low patient demand for medication treatment was reported as a barrier, and is an ongoing issue across the U.S., harboring support for medication treatment in the community by making medication treatment available and educating the public on its benefits might ultimately help the uptake of medications in the long run. Furthermore, a recent study found that most patients who decide to use agonist therapy did so after learning about it and its benefits from someone else who had been on it, suggesting that exposure to other patients with medication treatment experience might help promote the use of medications among others seeking treatment. Additional research will help identify why relatively few patients use these lifesaving medications and how we can promote their use among those who need them.

Compared to leaders whose organizations had already adopted agonist treatment, leaders whose organizations had not yet adopted agonist medication treatments had less positive attitudes toward agonist medications, were more likely to report agonist diversion and cognitive difficulties as barriers to implementation, and more likely to be concerned that providing agonist medications could put recovering staff and patients in abstinent-based recovery at risk of relapse.

Importantly, leaders who had started providing agonist treatment noted the ways in which they mitigated these concerns and address them at their organizations. For example, leaders noted that dosing within the clinic and limiting take-home doses helped to prevent diversion, and regular daily monitoring of patients helped guide prescribers with dose adjustments and limit patient side effects. In fact, many of the things that leaders reported as helping support the development and maintenance of an established agonist treatment program (e.g., strong leadership and organizational support for medication treatment) seemed to address the most commonly reported barriers and concerns reported among non-adopters. For example, non-adopters had concerns about treating patients on agonist treatment and patients seeking abstinence-based recovery in the same setting, whereas adopters noted this as one of the factors that supported them in providing agonists by creating common ground and a better understanding of the many paths to recovery. Therefore, many of the concerns that were reported as barriers among non-adopters seem to be readily addressable.

By ensuring strong leadership who understand and support medication treatment, hiring new staff with education and more positive medication attitudes and/or retraining current staff about the various paths to recovery and medication provision, organizations are more equipped to change their ideologies, support a positive and accepting environment for patients, and better address concerns like diversion and monitoring patient side effects (e.g., cognitive difficulties).

Despite the many concerns around providing agonist treatment, organization leaders had few concerns about antagonists, calling it underutilized, safe, and acceptable. Interestingly, none of the leaders noted lack of patient demand as a barrier to implementing antagonist treatment. Other studies have reported difficulties around starting patients on Vivitrol and keeping them engaged during the early stages of treatment (e.g., first couple of months). Therefore, it is unclear if the organizations are unaware of this scientific evidence, if they have had greater success with antagonists than the general population, or if leader’s attitudes toward medication influenced their tendency to respond favorably to antagonists. Nonetheless, antagonists appear to be perceived as an easier treatment to incorporate into organizations, calling for additional support to make leaders more comfortable with, and more equipped to implement, agonist treatments as well.

The rate at which a treatment is adopted is largely determined by stakeholders’ perceptions of that treatment. By gaining a better understanding of treatment organization leaders’ perceptions of OUD medication, we can better understand which characteristics of the treatment are hindering its large-scale provision and use. According to the diffusion model, there are five characteristics that determine the rate at which a new treatment is adopted within the community. When applied to the context of medication treatment they are: (1) the perceived relative advantage of medication treatment over other available treatments for OUD (e.g., psychosocial treatment), (2) the degree to which medication treatment is compatible with the values, experiences, and needs of relevant stakeholders (healthcare workers, patients, etc.), (3) the degree to which medication treatment is thought to be simple or hard to adopt and implement, (4) the extent to which medication treatment can be tried out or tested within a healthcare system, and (5) the extent that the benefits of medication treatment can be observed by others. In the context of this study’s findings, it seems important to address healthcare leaders’ perceptions of medication treatment, including its perceived lack of effectiveness relative to psychosocial treatment and perceived incompatibility with an abstinence-based recovery model. It will also be important to provide education and programmatic support to help make medication treatment easier to understand and implement, and to test various models of treatment within systems of care to see what works for different settings. By starting a new program of medication treatment, individuals will be able to observe its benefits for patients and the organizations that serve them, which will further support its adoption within the broader community.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The authors evaluated a set of interview themes that were largely defined at the start of the study (adoption of medication treatment, practical and logistical barriers, ideology, stigma, facilitators). Therefore, there may be other factors that act as barriers and were not assessed here.

- Organization leaders may not be fully aware of all of the barriers experienced by staff, or the procedural details of day-to-day operations within different sectors and programs. Furthermore, leader’s perceptions may not have represented the thoughts and beliefs of all healthcare providers in the organization. Leaders’ characteristics may have also influenced the attitudes reported here, as leaders were primarily white men. Some leaders also appeared to be in long-term recovery, and research suggests that older recovery cohorts may have more negative agonist attitudes. Additional large-scale studies are needed to compare beliefs across different roles and programs within organizations.

- Outcomes were not detailed according to the types of treatment organizations sampled (residential, outpatient, etc.). Furthermore, the researchers tried to oversample leaders from organizations that had not adopted any medication treatment. However, relative to other states, Philadelphia has a higher rate of organizations that have adopted medication treatment, and additional research involving more of these organizations, and those with different healthcare models, is needed to replicate this study’s findings and determine their applicability to the broader pool of treatment organizations in the U.S.

BOTTOM LINE

In this qualitative study of SUD treatment program administrators’ attitudes toward OUD medications, researchers found that participants had misperceptions about medication treatment, with most reporting that medication was not effective as a stand-alone treatment (without psychosocial therapy). Additionally, lack of resources, education, and programmatic knowledge among staff, as well as lack of patient demand for medication, were reported as barriers to implementing a medication treatment program. Leaders who had yet to implement agonist treatments (buprenorphine & methadone) also reported several concerns that acted as barriers, including medication diversion, cognitive difficulties from high agonist doses, and the fear that patients on agonist medications might trigger those in abstinence-based recovery to relapse. However, many leaders who had already started providing agonist treatment focused on ways that they addressed these concerns in their programs, suggesting that these concerns can be overcome. Factors that helped them implement successful agonist treatment programs included strong leadership, staff training / turnover, emphasizing “multiple pathways to recovery” in the organization, and observing the benefits that the new program has for the patients and organizations.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Individuals and families who are seeking treatment are encouraged to educate themselves about the various paths to recovery, including medication treatment and its benefits/risks, and discuss options with physicians at various organizations to help determine if this treatment is right for them. Discussing medication treatment with peers in recovery who have had experience with medication treatment might also help patients better understand what it is like. For those who decide to seek out a medication treatment program, finding a provider whose organization has sufficient resources and training to support their treatment journey might ultimately help aid a positive treatment experience and support recovery.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Although several barriers to providing OUD medication treatment were reported, some of them were misperceptions (e.g., medication is not effective without psychosocial treatment). These outcomes warrant more comprehensive programs that provide healthcare professionals, affiliated staff, and patients with guidance and education around medication treatment to support the new implementation and maintenance of medication treatment within organizations and help mitigate false beliefs and negative attitudes among staff and patients. Several factors were thought to facilitate the initiation and maintenance of a new pharmacotherapy program, including: (1) the presence of strong leadership that advocate for medication, (2) workforce turnover to foster organizational change, (3) redefining recovery throughout the organization to support multiple paths to recovery and de-stigmatize pharmacotherapy, and (4) observing patient improvements like enhanced retention and outcomes, in addition to financial benefits for the organization, which reinforced staff to continue efforts. Therefore, harboring a new ideology around treatment and recovery that challenges traditional ideals and stigma within the institution appear to be important elements for developing and sustaining a successful program of medication treatment.

- For scientists: Given that this study was conducted in the context of a single county/state, additional research in this area is needed to determine if findings apply to other healthcare settings and patient populations. Research that systematically tracks and evaluates program components and methods of new implementation will help determine the factors that actually impact the start-up and maintenance of medication treatment in healthcare organizations, whether perceived barriers and facilitators match those that are seen, and their effectiveness over time. Innovative programs aimed at educating treatment staff, cultivating more agonist-friendly attitudes, and initiating/maintaining new programs of medication provision should be developed and studied to enhance treatment access and provision.

- For policy makers: Resources were a commonly reported barrier to providing medication treatment, including a lack of educational and financial resources to start a new program of pharmacotherapy and support its patients. Additional funding can help support the development of comprehensive programs that educate staff on up-to-date evidence-based practices, mitigate stigma and debunk misconceptions about agonist treatments (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine), and better equip organizations and their staff to start and maintain such treatment programs (e.g., programmatic assistance with start-up and administrative maintenance). With the provision of medication treatment and healthcare organizations being highly heterogeneous across the nation, funding for additional research will help us understand the large-scale applicability of these findings and identify potential barriers in other healthcare settings.

CITATIONS

Stewart, R. E., Wolk, C. B., Neimark, G., Vyas, R., Young, J., Tjoa, C., . . . Mandell, D. S. (2020). It’s not just the money: The role of treatment ideology in publicly funded substance use disorder treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 120, 108176. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108176