National estimates of the use of medication and mutual-help groups in opioid use disorder treatment settings

How many patients in opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment receive FDA-approved OUD medications? How many participate in mutual-help organizations? How many do both? Previous research suggests that individuals taking medication for OUD may face resistance and reduced support from others when participating in mutual-help groups. This study provides estimates of the frequency of medication use and mutual-help for OUD and examines factors that make individuals more or less likely to use medication, mutual-help, both, or neither during treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) and participation in mutual-help organizations are both associated with an increased likelihood of abstinence among individuals with OUD. Individuals who use both have a greater likelihood of abstinence than individuals who use medication only, yet individuals using agonist medications for OUD can sometimes encounter anti-medication sentiments in abstinence-based mutual-help organizations. It is unknown, at a national level, how common it is for individuals in treatment for OUD to use medications, mutual-help, both, or neither. With greater understanding of the intersection between medication and mutual-help utilization among individuals with OUD, treatment providers and policy makers can capitalize on potentially additive benefits of these services. More specifically, given that mutual-help organizations are freely available, empirically supported recommendations for the use of these community-based groups may improve outcomes for individuals who are taking OUD medications. Emerging studies in this area have focused on individuals from single treatment programs or clinical studies. This study widened the perspective offered by these initial studies in the field to provide national estimates of these groups and examines factors that affect the likelihood of using medication and/or mutual-help, including treatment setting, referral source, type of insurance, race/ethnicity, and type of opioid use.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

In this study, the research team examined 447,966 discharges from outpatient (83%) and residential or inpatient (17%) treatment in the United States from 2015 to 2017. It is important to note that the researchers examined “discharges” from treatment, rather than individual people, as the dataset did not allow for tracking individual people. An individual could have been discharged from multiple treatments during the study window and thus count as two or more separate discharges. Adults in treatment primarily for opioid use were included in the sample. Treatment needed to last for at least 30 days. The data came from the Treatment Episode Data Set: Discharges (TEDS-D), which includes discharges from addiction treatment settings that receive public funds at both the state and federal levels.

At the time of discharge, discharges were categorized as being in one of four mutually exclusive groups:

Figure 1.

The authors then examined the likelihood of being in each of the four groups as predicted by:

Figure 2.

The authors controlled for age, sex, employment, homelessness, concurrent treatment for other substance use disorder, and co-occurring mental health problems in their statistical models. No further information about participants was provided.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Use of medication and mutual-help together was relatively rare.

Only 10% of the sample was using both mutual-help and medication at the time of discharge, with 29% using only medication, 30% using only mutual-help, and 31% using neither.

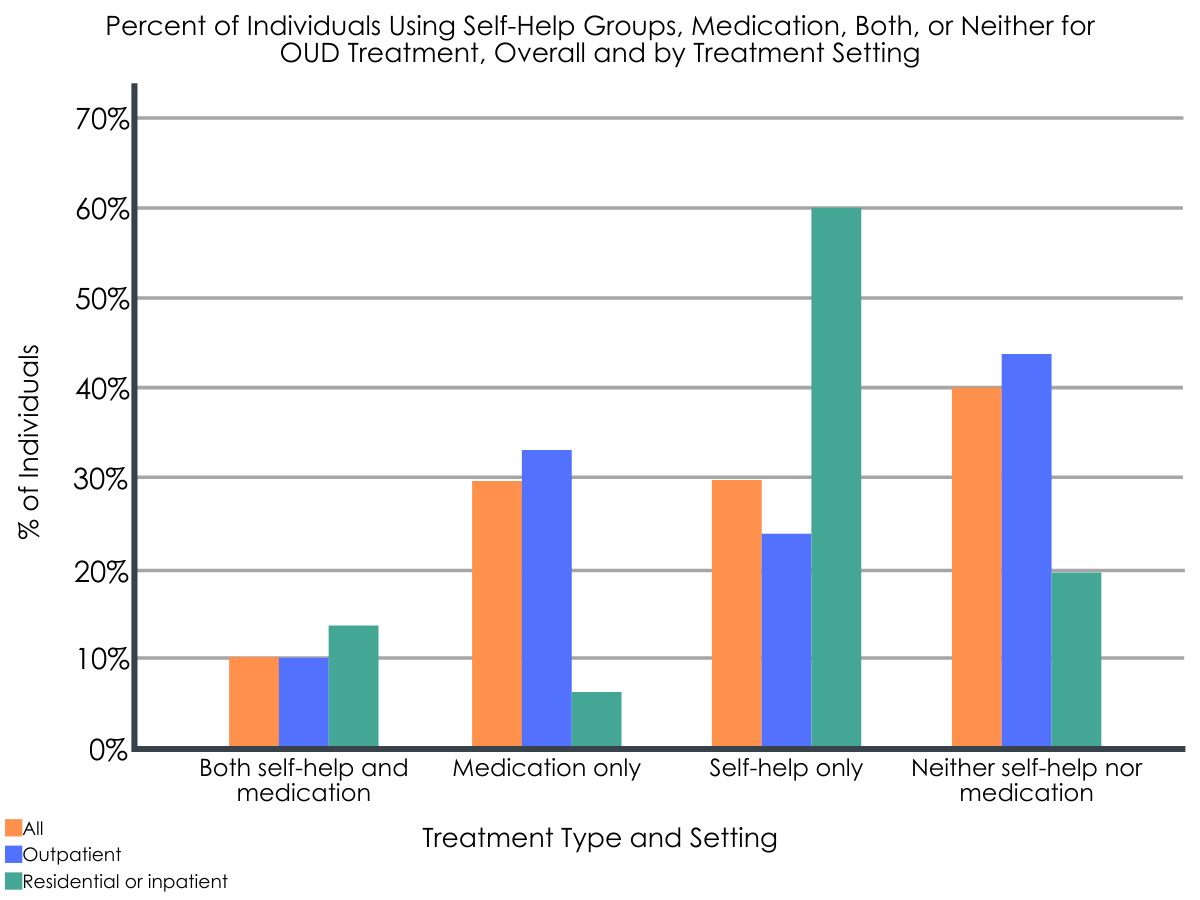

Mutual-help participation (with or without medication) was more common in inpatient/residential settings, whereas medication alone was more common in outpatient settings.

Discharges from inpatient or residential settings were more likely to attend mutual-help meetings prior to discharge, either alone (60%) or in combination with medication (14%), compared to outpatient discharges (24% and 10%, respectively). Conversely, outpatient discharges were more likely than inpatient/residential discharges to use only medication (33% vs. 6%, respectively), or neither medication nor mutual-help (33% vs. 20%).

Figure 3.

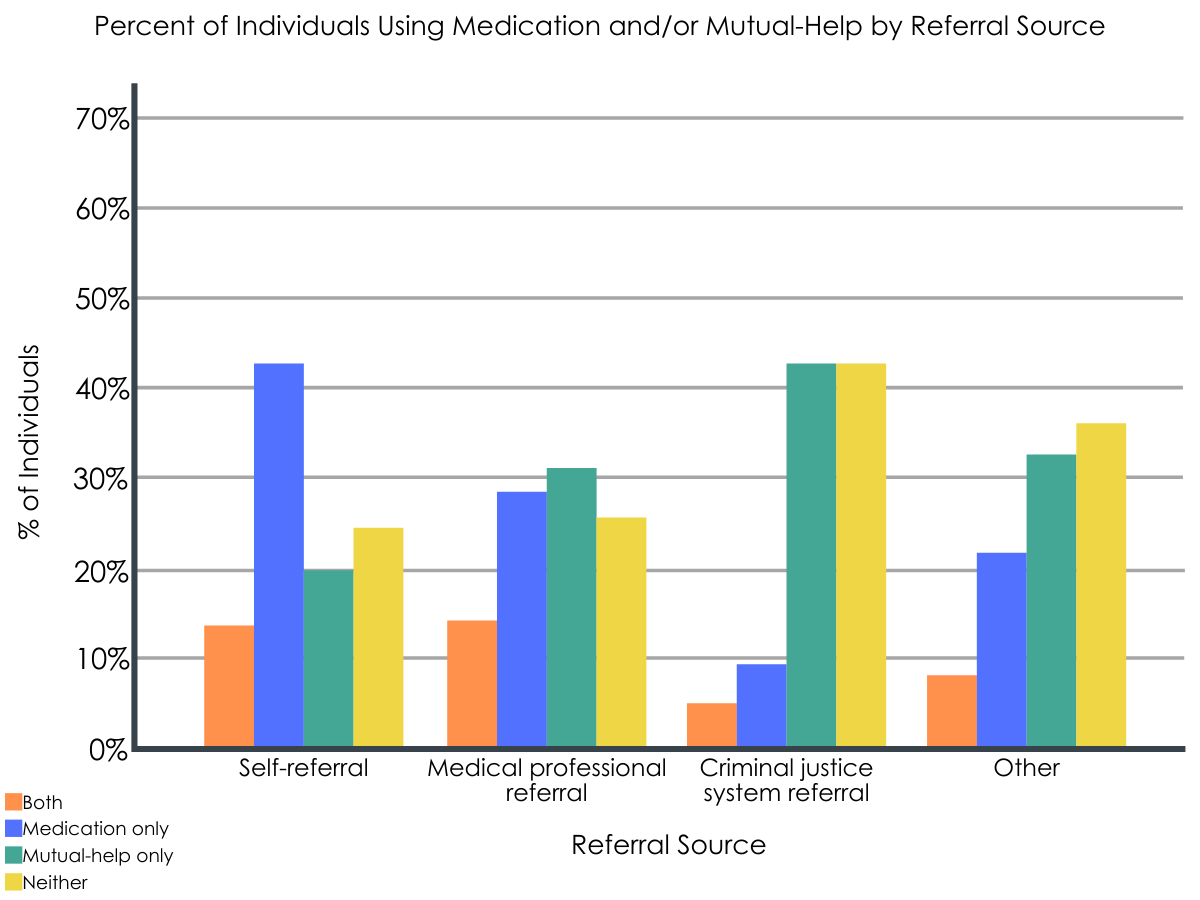

Criminal justice system referrals were the least likely to include medication compared to other referral sources.

Criminal justice system referrals, which made up 27% of the dataset, were the least likely to use medication, either alone (9%) or in combination with mutual-help (5%). This is compared to 43% of self-referrals and 28% of medical professional referrals who used medication alone, and 13% of self-referrals and 14% of medical professional referrals who used both medication and MHGs.

Figure 4.

Discharges covered by Medicaid were the most likely of all insurance types to include medication.

Nearly half the sample consisted of discharges covered by Medicaid. The use of medication was most common in this group, either alone (26%, compared to 19-22% of other referral sources) or in combination with mutual-help (11%, compared to 6-8% of other referral sources). There were no differences in the use of mutual-help alone or in using neither medication nor mutual-help across different types of insurance.

Non-Hispanic White discharges were the most likely to use both medication and mutual-help, whereas Hispanic/Latino discharges were the most likely to use neither.

Non-Hispanic White discharges used both medication and mutual-help (11%) at a higher rate than discharges who were Black/African American (9%), Hispanic/Latino (8%), or other races/ethnicities (9%). Hispanic/Latino discharges were more likely to use neither medication nor mutual-help (35%) than discharges who were Black/African American (32%), Non-Hispanic White (30%), or other races/ethnicities (29%).

Medication (with or without mutual-help) was more frequently used among discharges being treated for heroin use.

Those treated primarily for heroin use were more likely than those treated primarily for other opioids to use medication, either alone (32%) or in combination with mutual-help (11%), compared to discharges being treated primarily for other opioid use (21% and 7%, respectively). In contrast, mutual-help attendance only (32% vs. 29%) and neither medication nor mutual-help (39% vs. 28%) was more common among those treated for other opioids.

There was an inverse relationship between medication and mutual-help use at the state level.

When examining state-level differences, there was generally an inverse relationship between mutual-help attendance and medication use, such that in states where medication use was more common, mutual-help attendance was likely to be lower. Medication use tended to be greater in the Northeast and Puerto Rico and mutual-help attendance only was greatest in the South and West.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found that taking advantage of both medications and mutual-help during treatment, especially outpatient treatment, is relatively rare. Only 1 in 7 discharges from inpatient/residential OUD treatment and 1 in 10 discharges from outpatient OUD treatment used both medication and mutual-help at the time of discharge. While this study did not examine the reasons behind the low rates of combined use of medication and mutual-help, other studies have noted that individuals on opioid medications, such as buprenorphine and methadone, may encounter negative messaging and attitudes in 12-step mutual-help meetings. In program literature for Narcotics Anonymous (NA), there is explicit acknowledgment that some meetings may restrict attendance of individuals taking agonist medications. As a result, patients may either stop attending meetings or stop using medication. Despite these barriers, prior research has found that mutual-help group attendance is associated with increases in the likelihood of abstinence among people receiving medications for OUD. Individuals in buprenorphine maintenance treatment who attend mutual-help groups are also more likely to be retained in treatment. While using both medication and mutual-help was uncommon, 60% of the sample used either medications or mutual-help at the time of discharge. This is encouraging, as these resources have both been found to be independently associated with abstinence from opioids.

This study also found that discharges who were referred to treatment by the criminal justice system were especially unlikely to use medications for OUD. Only 1 in 7 criminal justice system referrals used medications, compared to more than half of self-referrals and nearly half of medical professional referrals. This difference in the use of medications for opioid use may reflect the high level of opposition to the use of medications, especially opioid agonist medications such as buprenorphine and methadone, among correctional agents and court systems in the United States. It may be especially critical to expand the use of medications for opioid use in the criminal justice population, as prior research has found that the use of opioid agonist medications during incarceration can decrease the risk of overdose death by 85% in the month following release from incarceration. While the sample in the present study did not include individuals who were currently incarcerated, 27% of the sample were referred by the criminal justice system and thus may be at risk of being incarcerated at some point.

This study found a difference across racial/ethnic groups in the combined use of medications and mutual-help, with White discharges being the most likely to use both. Hispanic/Latino discharges were the most likely to use neither medication nor mutual-help. It will be important for future research to examine the reasons behind these differences to reduce barriers to treatment. In contrast, there were no differences across racial/ethnic groups in the use of medications alone or mutual-help alone. This suggests an improvement from prior research from an earlier time period (2002-2015), which showed that White individuals were more likely to receive buprenorphine than Black individuals. It remains crucial to ensure that individuals have equitable access to treatment resources, regardless of race or ethnicity.

This study found that individuals on Medicaid were the most likely to use medications, either alone or in combination with mutual-help, compared with other insurance types. This is consistent with prior research showing a marked increase in the prescription of buprenorphine and naltrexone in states that expanded Medicaid eligibility. While this study did not examine the reasons for these differences, the findings suggest that reducing the cost to patients of medications may decrease barriers to using them. Medicaid expansion may also reflect the political leanings of a state in relation to policies for individuals who use drugs, with more progressive states allowing for more widespread access to OUD medication prescriptions. Interestingly, discharges who were uninsured were no less likely to receive medication than those with private insurance or Medicare or other coverage. There were no differences in the use of mutual-help alone across different types of insurance. This is not surprising considering that a hallmark of mutual-help is that it is freely accessible to all individuals and does not require insurance.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This was a cross-sectional study, meaning that data were examined at a single time-point for each case (i.e., discharge from treatment). Thus, the study does not provide information about how the use of medications, mutual-help, both, or neither changed over time, and whether and how that relates to outcomes.

- No information was provided on what treatments were available in each setting. Thus, it is not known whether individuals who did not take medications for opioid use were offered these medications during treatment.

- No data was provided on type of mutual-help group attended, frequency of attendance, or level of involvement in meetings. However, the researchers noted that results were similar when they examined weekly attendance (versus any attendance in past 30 days). It would be interesting to know whether individuals who both attended mutual-help and took medication attended mutual-help groups that were openly accepting of medication (e.g., Methadone Anonymous, SMART Recovery).

- No information was provided on the specific OUD medications used, although the authors note that their sample likely follows national trends of being mostly agonist medication (i.e., buprenorphine, methadone). It is not possible to determine whether individuals who both attended mutual-help groups and took medication were more likely to use antagonist medication (e.g., naltrexone) than agonist medication.

- The authors did not perform a head-to-head comparison of predictors to see which was most influential on group assignment. Thus, it is not possible to determine the relative importance of treatment setting, referral source, type of insurance, race/ethnicity, type of opioid use, and geographic location in predicting the use of medications, mutual-help, both, or neither.

- The study team chose to control for sex, age, and other variables instead of analyzing them as predictors. It may be that these variables also covary with the use of these different types of treatment and recovery support services.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Patients and families should be aware of prior research showing that the combination of medication and mutual-help is associated with improved outcomes. Patients and families, particularly those from demographic groups or geographic locations where the combined use of medication and mutual-help is less common, may need to advocate for access to medications and seek out mutual-help groups on their own in order to get the most benefit out of treatment.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treatment professionals and systems treating patients with OUD should systematically refer individuals to mutual-help organizations and offer medication to help individuals get the most benefit from treatment. Providers should be prepared to help patients identify groups that are openly accepting of opioid agonist medications (e.g., SMART Recovery), or to navigate situations where they encounter negative messages about medications in mutual-help meetings that they experience as helpful. If treatment professionals and systems explore and work to reduce barriers to accessing medications and/or mutual-help among populations that may be less likely to use these resources (e.g., individuals involved in the criminal justice system; Hispanic/Latino individuals), patients outcomes may improve

- For scientists: Future research could build on this study by doing head-to-head comparisons of predictors to determine the relative importance of treatment setting, referral source, type of insurance, race/ethnicity, type of opioid use, and geographic location in predicting the use of medications, mutual-help, both, or neither. Future longitudinal research could examine the trajectories of the use of medication and mutual-help over time to determine how the use of these treatment resources predicts outcomes. Ultimately, randomized trials and/or rigorous quasi-experimental work that test different strategies for adding mutual-help group facilitation to OUD medications, followed by dissemination efforts to implement what was learned, is likely to yield the greatest real-world benefits for individuals and public health more broadly.

- For policy makers: Findings highlight the potential public health benefits of (a) funding education within the criminal justice system on the importance of medications for OUD; (b) expanding Medicaid coverage in all states in order to increase access to life-saving opioid treatment medications; (c) increasing advocacy for equitable access to evidence-based treatments across all racial and ethnic groups.

CITATIONS

Wen, H., Druss, B. G., & Saloner, B. (2020). Self-help groups and medication use in opioid addiction treatment: A national analysis. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 39(5), 740–746. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01021