Discrimination against transgender people associated with higher rates of substance use and treatment

Transgender people face discrimination in a variety of settings, including the housing market, employment, health care, and interactions with law enforcement. Building on earlier research, this study shows a positive correlation between the severity of discrimination faced by transgender people and higher rates of substance use, substance use disorder, and substance use disorder treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Transgender people (whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth) face discrimination and stigma in many forms, including verbal harassment, threats, violence, and mistreatment in everyday interactions. Such discrimination can have both a direct negative impact on the mental health of transgender people—associated with posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, suicide attempts, and substance use—and reduce access to resources including healthcare, housing, and employment. An earlier study established that substance use is higher among transgender people than the general U.S population. Others studies have shown that transgender individuals may use substances to cope with the stress of stigma and that higher levels of discrimination are associated with higher levels of substance use. Research that examines the relationship between substance use and discrimination can inform the development of interventions tailored to this vulnerable group, including both substance use disorder (SUD) prevention as well as treatment and recovery supports. In this article, Wolfe and colleagues examined the relationship between lifetime experiences of transgender related discrimination and three substance use outcomes: past 12-month substance use, lifetime SUD diagnosis, and lifetime treatment history.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

The authors collected data by surveying 600 transgender adults who live in Massachusetts and Rhode Island between March and August 2019. Most survey data was collected online. However, they also recruited individuals offline to better reflect populations that either were housing insecure or did not have access to internet. The authors classified respondents into two overarching groups, “trans feminine” and “trans masculine,” to provide more context regarding gender identities and sex assigned at birth. Within each of the trans feminine and trans masculine groups, individuals were additionally categorized as binary (man, woman, trans woman/male-to-female, trans man/female-to-male) or non-binary (non-binary, gender variant, gender fluid, quencher nonconforming, or other).

The study evaluated experience of life-time discrimination utilizing a version of the Everyday Discrimination Scale (modified to include transgender-related discrimination) and divided total scores into four categories: low, low to moderate, moderate to high, and high. Using this instrument, the research team also collected information about experiences of discrimination related to race, age, HIV status, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, physical disability, education or income level, weight, and other aspects of physical appearance. The authors developed a new scale to measure past year substance use by asking respondents how often they used to “get high.” Participants ranked how frequently they used a drug from a comprehensive list of substances (cannabis, cocaine, club drugs etc.) on a scale of 0 to 5. The researchers then summed these scores. The result was a single score that reflected both the number of substances used and the frequency with which each substance was used. Finally, they evaluated whether respondents had been diagnosed with an SUD or received SUD treatment in their lifetime by asking participants to answer “yes/no” questions regarding each.

The research team examined how strongly lifetime experience of transgender discrimination was associated with past year substance use, lifetime SUD diagnosis, and lifetime SUD treatment. The collection of data regarding other forms of discrimination allowed the authors to control for these factors and therefore separate out transgender discrimination from other experiences of stigma that transgender people often face. The authors created a variable of “discrimination experiences other than being transgender.” In their statistical analysis, they were able to adjust for this variable and other factors known to be associated with substance use outcomes among transgender people (such as age or intimate partner violence).

Most study participants were white (81.4%). One third of the sample had a 4-year college degree (33.3%); 64% of the participants identified as transmasculine and 42.2% identified as nonbinary, gender variant, gender fluid, gender queer, or gender nonconforming. Almost half of participants (48.6%) had a pretax income of $20,000 or less. The vast majority of participants took the survey online (95.3%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Large number reported discrimination.

A large proportion of the respondents reported experiencing discrimination related to being transgender (87.4%) Almost half of the study participants (48.2%) reported moderate to high levels of discrimination in the past 12 months.

High transgender discrimination associated with past year substance use.

In contrast to lower transgender discrimination scores, high transgender discrimination was associated with more past 12-month substance use. Being a person of color and experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) were also associated with more substance use. Age and other reasons of discrimination (e.g., ethnicity, sexuality) were associated with less substance use.

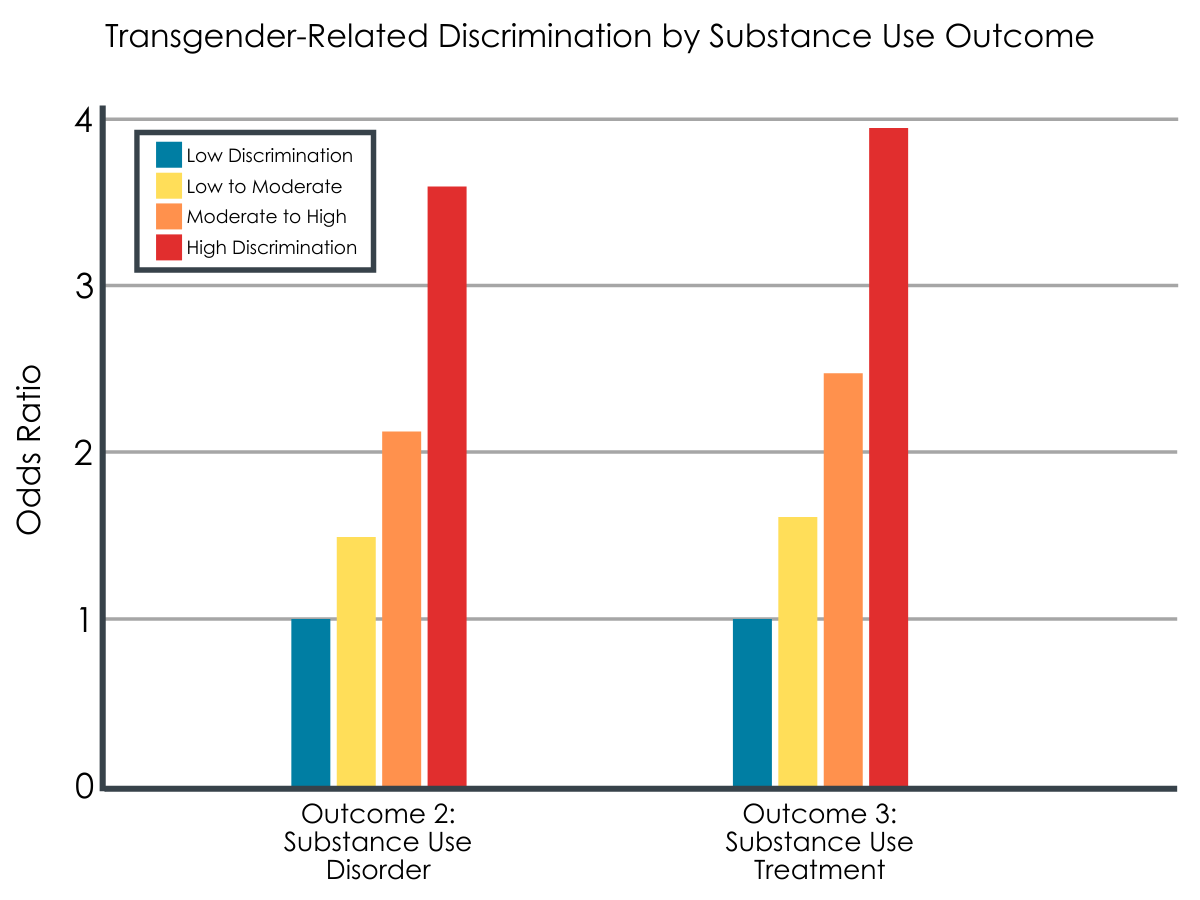

High transgender discrimination associated with lifetime SUD diagnosis.

In contrast to lower transgender discrimination scores, high transgender discrimination was associated with more than 3 times greater likelihood of a lifetime SUD diagnosis. Experiencing of intimate partner violence (IPV) was the only other variable that increased the likelihood of a SUD diagnosis. Trans masculine identity and being a person of color decreased the likelihood of a SUD diagnosis.

High transgender discrimination was associated with lifetime SUD treatment.

In contrast to lower transgender related scores, moderate-to-high and high transgender discrimination made it more likely for an individual to have attended SUD treatment. Older age also increased the likelihood of having attended treatment.

Reported outcome measures. The researchers reported their findings as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for Outcomes 2 and 3. With the Low Discrimination group acting as a reference point (OR = 1), an OR more than 1 indicates an increased risk of a substance use diagnosis or having received substance use treatment for that discrimination group, as compared to the Low Discrimination group.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study aligns with earlier research showing that a high percentage of transgender people experience discrimination and may turn to substance use as a means of coping. This finding has important implications for both health professional that work with transgender people and SUD treatment providers. Given the association between transgender discrimination and substance use, screening for SUD should be routine element of care for transgender people. For providers working with transgender people who use drugs, such as heroin, including non-problematically or at levels below the threshold of a SUD diagnosis, providing harm reduction support such as Naloxone, sterile syringes, and safer drug use education may be an important part of care. Harm reduction-based brief interventions for alcohol have been shown to work in a variety of groups and may also prove helpful for transgender individuals, although their level of efficacy among sexual and gender minorities requires further research.

Transgender people frequently report discrimination in health care settings, including with SUD care. Earlier research shows that some transgender individuals leave treatment out of fear or actual experiences of discrimination. It is important that SUD treatment providers ensure that staff receive adequate education regarding transgender mental health/SUD issues as well as the potential impact of stigma and discrimination on treatment. In addition to addressing stigma within treatment settings through education and/or policy, it may be useful to introduce specific support for transgender people—mutual help groups, group therapy sessions—within settings whose focus is on providing SUD treatment to broader populations.

The present study raises the possibility that not addressing the stigma and discrimination around transgender stress may be counterproductive or harmful. The association between transgender discrimination and substance use suggests that developing alternative resources and skills to cope with the psychological impact of stigma might be an important aspect of recovery for transgender people. Providers Because the evidence-base is thin regarding empirically supported models for transgender person, clinicians might need to innovate and develop ways of addressing experiences of stigma and discrimination as an integral part of providing SUD care for transgender people to enhance treatment engagement and benefit.

The authors interpret their findings using “minority stress theory,” a framework that proposes that sexual minorities make use of substances in order to manage stress produced by discrimination and social marginalization. The study’s finding of a relationship between the highest level of discrimination and higher levels of substance use lend support to this theory. At the same time, the finding that a “moderate-to-high” level of discrimination was not associated with greater substance use or SUD diagnosis suggests that the relationship between discrimination and substance use may be complex or involve additional factors.

Research shows that people who drink heavily are more likely to experience a range of harms, and sexual minorities who drink heavily are more vulnerable to assault/physical harm than their heterosexual counterparts. It is possible that greater levels of substance use or the presence of SUD increases the vulnerability of transgender people to discrimination. While transgender individuals may turn to substance use as a result of stigma, greater levels of substance use or SUD might in some cases render individuals more vulnerable to discrimination that is already socially prevalent. Additionally, the finding that “moderate-to- high” levels of discrimination are not associated with increased substance use or SUD diagnosis suggests that there may be additional factors that protect against both discrimination and substance use.

This study also reports some unexpected findings that merit further exploration. Transgender people facing a high amount of discrimination appear to report rates of treatment higher than the general population despite this group’s experience of stigma in treatment settings. The study also found that other reasons for discrimination were protective against substance use and that trans masculine identity and being a person of color were protective against SUD diagnosis. Further research is required to see if these findings hold in other settings and to understand their implications.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- As the authors acknowledge, this is an observational study based on a single sample. The majority of the participants were white, younger, and highly educated and all of them came from two U.S. states (Massachusetts and Rhode Island). While informative, the findings may or may not be generalizable to other populations of transgender people.

- The authors assess lifetime SUD rates by asking respondents if they have received an SUD diagnosis. However, a patient generally receives an SUD diagnosis in the course of treatment. The fact that the rates of lifetime SUD diagnosis (11.8%) and SUD treatment (11.6%) are similar suggests that these statistics are both reflections of SUD treatment rates. This study therefore may not be capturing the full extent of SUDs among transgender people.

- The authors interpret the positive association between transgender discrimination and substance use treatment in terms of the discrimination that transgender individuals may have experienced in treatment settings. This is plausible. Another possibility is that life-time discrimination contributes to more severe SUDs that, in turn, result in higher rates of treatment. Longitudinal research that follows individuals over time is needed to better understand the relationship between transgender discrimination and SUD treatment rates.

- The authors measure substance use by assessing the frequency (on a scale of 0 to 5) that individuals use 10 substances and then combining the score for each substance together (creating a potential outcome of 0 to 50). While a useful index, measuring frequency of use and number of substances used does not distinguish between recreational use, use for affect management (“self-medication”), and use in the context of an SUD. Additionally, frequency of use may not be comparable in terms of health and social impacts between different substances (for example, daily cannabis and daily fentanyl use). More research on motivation, context, and consequences of use are necessary to have a fuller understanding of substance use among transgender people.

BOTTOM LINE

This study aligns with earlier research showing that a large number of transgender people experience discrimination and may turn to substance use as a means of coping. Given the association between transgender discrimination and substance use, screening for harmful substance use and SUD should be routine element of care for transgender people. It is important that SUD treatment providers ensure that staff receive adequate education regarding transgender mental health and SUD-related issues. The association between transgender discrimination and substance use suggests that developing alternate resources and skills to cope with stigma might be an important aspect of recovery for transgender people. Providers should consider ways of addressing experiences of stigma and discrimination as an integral part of providing SUD care for transgender people.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: A high percentage of transgender people experience discrimination and may turn to substance use as a means of coping. Because discrimination is linked with higher levels of substance use, developing resources and skills to manage the psychological stress of this may play an important role in the recovery of transgender people. Many transgender people report experiencing mistreatment in healthcare settings, including in treatment for SUD. When possible, transgender people seeking recovery should consider seeking out programs with a focus on transgender mental health or where the staff receive training regarding LGBQT+ issues. Transgender people may also find greater understanding of their experiences in mutual help meetings that are LGBQT+ focused (such as Alcoholics Anonymous meetings that are advertised specifically for this group). Many such meetings are now available online.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This study suggests that many transgender people, especially those who face the highest degree of discrimination, turn to substance use to manage the impact of stigma and discrimination. Helping transgender clients develop new supports and/or skills to manage the psychological cost of social marginalization may be a critical part of supporting their recovery. It is important that clinicians give transgender clients the space to explore how these questions might relate to their experience of SUD. Many transgender people report experiences of discrimination in health care settings, including within SUD treatment. Earlier research shows that some transgender individuals leave treatment out of fear or actual experiences of discrimination. SUD treatment professional and providers should consider pursuing education regarding issues surrounding transgender mental health and, when appropriate, introduce policies that address stigma and discrimination against transgender people. Treatment programs should be affirming of people’s gender identities and able to address experiences of stigma and discrimination as an integral part of providing SUD care for transgender people.

- For scientists: This study adds additional support to a growing literature showing the association between discrimination experienced by transgender people and higher levels of substance use, substance use disorder, and substance use disorder treatment. Further longitudinal and qualitative studies are needed to better understand the relationship between transgender discrimination, substance use, and treatment rates. An important focus of future research should be how transgender people themselves understand these questions. Such research is critical to developing and evaluating targeted interventions designed to help transgender individuals cope with and respond to discrimination.

- For policy makers: This study adds to the growing literature that links discrimination against transgender people and higher rates of substance use, SUD, and substance use treatment. At the systems level, this finding suggests that discrimination and stigma in healthcare, employment, housing, and the criminal justice system has a knock-down effect on the rate of substance use and SUD among transgender people. Laws and policies protecting transgender people from discrimination in these and other domains may be important for reducing rates of substance use, SUDs, and demand on SUD treatment. This research reaffirms earlier research suggesting that social determinants of health, such as discrimination and unequal access to resources like housing, may play a significant role in mental health and substance use of transgender people and therefore should be incorporated into policy approaches to these questions. This study also calls attention to the importance of SUD treatment programs that are gender affirming and offer specific services for transgender people and other LGBQT+ groups. Only a small number of treatment programs offer services specifically designed for sexual or gender minorities, despite the greater behavioral health care needs of transgender people. More funding support and research is likely to improve health outcomes and quality of life for this group.

CITATIONS

Wolfe, H. L., Biello, K. B., Reisner, S. L., Mimiaga, M. J., Cahill, S. R., & Hughto, J. M. W. (2021). Transgender-related discrimination and substance use, substance use disorder diagnosis and treatment history among transgender adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 223, 108711. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108711