Novel harm-reduction approach to alcohol treatment shows promise among individuals experiencing homelessness

Currently over half a million individuals experience homelessness, and nearly half of them meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder. Few treatments have successfully helped improve outcomes in this vulnerable group. This study tested a novel approach, Harm-Reduction Treatment for Alcohol (HaRT-A) – a 4-session, person-centered treatment that emphasizes harm reduction rather than total abstinence.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Individuals who experience homelessness have higher rates of alcohol use disorder relative to the general population and are less likely to receive alcohol treatment. Developed with input from individuals who would receive the treatment themselves (i.e., “consumers”), and expert clinicians who provide care to individuals with alcohol use disorder and who are experiencing homelessness, HaRT-A offers harm reduction-based treatment, over 4 sessions, designed to decrease alcohol use, related harms, and improve quality of life. Harm reduction approaches are highly person-centered and emphasize individuals’ autonomy and quality of life over total abstinence. This orientation may be both appealing and effective for homeless individuals with alcohol use disorder who may feel disempowered, and also prioritize quality of life over total abstinence. This study tested HaRT-A against services–as–usual for this vulnerable group, who experience added barriers when it comes to benefitting from treatment.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This team developed HaRT-A using a “community-based participatory research” strategy, which incorporates the views of members of the target community in the research planning, intervention development, and execution. For this study, researchers interviewed 50 homeless individuals with alcohol use disorder, as well as a panel of advisors and expert providers, to create HaRT-A. HaRT-A is a skill-focused intervention built on motivational interviewing principles. Each session focuses on personalized drink tracking, progress monitoring toward personalized quality of life goals, and discussion of safer drinking behaviors and coping strategies.

The phase of this study on which we focus here was a randomized controlled trial of HaRT-A among 169 homeless individuals, with alcohol use disorder, who were recruited from community-based health and social service agencies in Seattle, Washington. Half of the participants in the study were randomly assigned to receive HaRT-A within community-based clinics, while the other half received services–as–usual, which did not address alcohol use. Participants in the HaRT-A treatment group were scheduled to attend 3 weekly therapy sessions, plus a “booster” session one month later. Participants who were not assigned to receive the treatment had access to “services as usual.” This included access to outreach, case management, nursing and medical services, and assistance with food, clothing, etc. Notably, services–as–usual did not target alcohol or other drug use or mental health challenges. These services were also available to individuals who received the HaRT-A treatment. The researchers then monitored participants’ motivation (i.e., interest in, readiness for, and confidence in reducing their alcohol use over time), alcohol use (using both self-report and urine toxicology screens), negative consequences resulting from alcohol use, and quality of life at the start of the study and at the end of weeks 1, 2, 3, 7, and 12. The researchers then tested whether participants who received HaRT-A had better improvements over time compared to those receiving services–as–usual.

The majority of the sample had severe alcohol use disorder (82%; 10% had moderate), and 78% also reported use of cannabis, crack cocaine, or methamphetamine as well. Most participants were men (76%) and the average age of the sample was about 48, with most participants ages ranging between 38 and 58. The majority of the participants were Black or African American (58%), followed by White/European American (22%), American Indian/Alaska Native/First Nations (12%), multiracial (5%), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (1%). An additional 3% reported “other” as their race and 8% were Hispanic/Latinx.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Receipt of HaRT-A treatment led to some improved outcomes among individuals diagnosed with alcohol use disorder and currently experiencing homelessness, but findings were mixed.

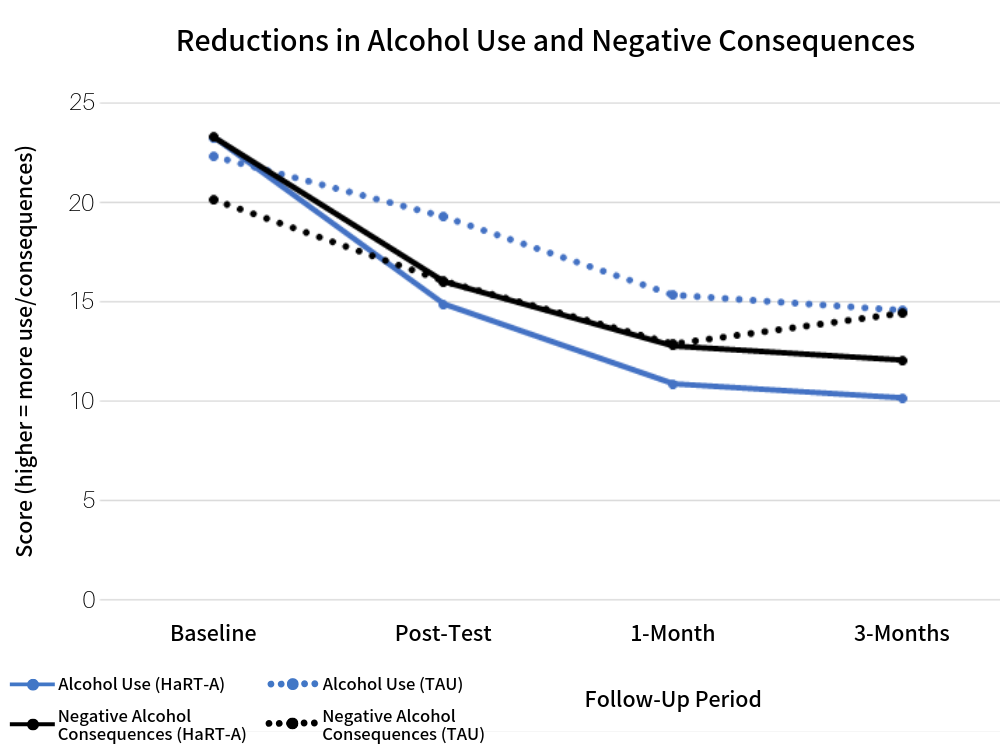

Compared to participants who received services–as–usual, participants who received the alcohol-focused HaRT-A intervention showed significant increases in their confidence to change their drinking, and reductions in alcohol use, negative alcohol use consequences, and alcohol use disorder severity. The alcohol consumption outcomes that showed the most improvement were greatest number of drinks in a drinking day in the past 2 weeks (“peak alcohol consumption”) and number of negative (signifying no recent drinking) urine toxicology screen results.

While experiencing improvements in key outcomes, HaRT-A participants unexpectedly did not improve on several others compared to usual services

The research team found that HaRT-A did not have an observed impact on individuals’ readiness to change their drinking or the importance they placed on changing their drinking. They also did not find that HaRT-A led to decreases in the number of days participants drank to intoxication, likelihood of achieving abstinence from alcohol, or quality of life.

In summary, overall, despite common concerns that harm-reduction approaches might encourage or “enable” unhealthy drinking behavior, results from this study demonstrate that HaRT-A did not harm individuals and did have positive impacts on several key alcohol outcomes.

Figure 1. Blue lines represent change in peak alcohol use (highest number of drinks in a single day in the past 2 weeks) at each time point in the study. Black lines represent changes in negative consequences (on a scale from 0-45) associated with drinking from the past 2 weeks, measured at each time point. Solid lines represent HaRT-A participants, TAU represents control group participants.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Individuals experiencing homelessness are at especially high risk for developing alcohol use disorder. Only a minority of these individuals seek treatment and of those who do, few complete treatment. HaRT-A is an alcohol use intervention that was shown to be effective compared to services–as–usual, which did not include alcohol intervention. That is, HaRT-A was not compared to abstinence-based treatment or any other specific treatment. Rather than compare it to no alcohol intervention, it would have been more fruitful and informative to compare it to a more straightforward brief motivational intervention (BMI) (e.g., 4 sessions of motivational interviewing focused on alcohol) to help determine the extent to which the added cost and training involved in implementing the HaRT-A intervention yields any additional incremental benefits. Consequently, future research is needed to evaluate HaRT-A against other evidence-based treatments, including a more straightforward BMI or abstinence-based approach. Nevertheless, this research is significant and innovative, in the sense that it shows positive effects of HaRT-A among homeless individuals primarily with severe alcohol use disorder, which most might believe require abstinence-based treatment (where zero alcohol use is the goal and standard to maintain in recovery). It is also noteworthy that the effects of the intervention persisted over 3 months, suggesting that improvements may be maintained at least over the short-term.

Importantly, this intervention is highly person-centered, designed to “meet individuals where they are at” in treatment, without imposing expectations on individuals seeking treatment. It is also designed to be executed over 4 brief therapy sessions, which may increase likelihood that individuals complete a full course of the treatment. Its brevity may limit the barriers to clinicians learning and implementing this treatment. Consistently, Collins and colleagues found that clinicians were able to learn HaRT-A and deliver it in a highly consistent and effective manner across participants. This suggests that, if shown to be effective in other studies and settings compared to a more straightforward standardized BMI, HaRT-A may be ripe for broader dissemination and implementation because of its greater ability to address the specific needs of homeless individuals with AUD.

Of note was that the motivationally-based, alcohol-focused HaRT-A intervention did no better than the non-alcohol–focused services-as-usual in increasing readiness for change, days drinking to intoxication, or quality of life. This is somewhat surprising given a major purported mechanism for interventions such as HaRT-A to work is by positively shifting readiness to change. The lack of an effect on days of alcohol intoxication is also surprising given that it is intoxication which is typically associated with the kinds of accidents and injury harms that presumably the intervention was attempting to prevent.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The brief 4 session and time-limited format might explain why the treatment did not lead to changes in all measured outcomes, including quality of life.

- Even though this sample was representative of homeless individuals nationwide in terms of age and race, further research is needed to determine how well this treatment works for youth, other racial/ethnic minority groups (e.g., Latinx), and in regions outside the large, resource-rich Pacific Northwest city in which this study took place.

- One strategy suggested as part of this intervention was to substitute alcohol use with moderate use of cannabis, which is legal in the state of Washington. This strategy may not be appropriate in states where cannabis use is not legal or available for recreational use.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The decision to seek help can be very difficult and many services focus on helping individuals abstain from alcohol use. This study suggests that homeless individuals can improve by reducing alcohol use, or reducing the harm associated with drinking, by switching from liquor to beer, slowly reducing quantities over time, or drinking in a safe places and avoiding high–risk situations (e.g., situations that trigger heavy drinking or negative consequences). Advocating for services that are consistent with your goals is a good start. With the help of trained professionals, harm-reduction approaches can help. In addition, for individuals experiencing homelessness (or for those concerned about others they care about), free self-help options might also be of interest. Examples of free, abstinence-based self-help group options include Alcoholics Anonymous, and non-secular options such as SMART Recovery, Secular Organizations for Sobriety, Women for Sobriety, or LifeRing. For individuals more interested in reducing or moderating their drinking, Moderation Management groups and resources may be of interest.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: HaRT-A is a harm reduction approach that may help improve several drinking and related outcomes, compared to services–as–usual (e.g., case management), and may expand clinicians’ repertoire by providing an alternative approach to treatment for homeless individuals with alcohol use disorder. Though contrary to some conventional wisdom, this research supports the use of harm-reduction approaches to treat alcohol use disorder. While more studies are needed to test this harm reduction alcohol use disorder approach against other types of interventions (e.g., standard BMI), HaRT-A shows promise in being able to engage a vulnerable group of individuals, and enhance their drinking outcomes. This article provides further evidence of that, as well as a particular intervention providers might consider using in their practice. What is not known currently is if there is any additional advantage to learning and providing HaRT-A over a more standard brief motivational intervention addressing alcohol.

- For scientists: HaRT-A was found to improve several drinking outcomes among homeless individuals with alcohol use disorder. Others that were anticipated to improve did not. This study used a prospective randomized controlled trial method to evaluate HaRT-A against existing services, and using an attention-matched control (i.e., same number of assessment sessions scheduled for control and treatment participants). These findings therefore provide promising initial outcome data upon which to base future research. Follow–up research would benefit from incorporating recommendations from affected community members not represented in the current sample, incorporating their recommendations in subsequent treatment modifications, and replicating the study as needed. Future research is also needed to examine mechanisms of action to inform future enhancements to the intervention, as well as examine its comparative efficacy to active controls and other interventions (e.g., BMI, SBIRT, 12-step facilitation, or abstinence–based CBT), or whether the intervention could be abbreviated even further. Lastly, participant retention in the treatment condition started from 100%, then dropped to 77%, 79%, and 73% for sessions 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Though this demonstrates reasonably strong adherence, future research may benefit from examining reasons for dropout to determine modifications needed to maximize adherence.

- For policy makers: This study showed that compared to not focusing on alcohol among homeless individuals, a brief, harm reduction approach for alcohol use disorder may be efficacious, and can be tailored to the needs of targeted members of communities. Over half a million individuals are currently experiencing homelessness, and alcohol use disorder remains among the most common medical and mental health conditions among these individuals. Alcohol use, in turn, is associated with worse life outcomes. This study offers preliminary evidence of the positive impact of ongoing funding for treatment development research targeting individuals with alcohol use disorder broadly, as well as those experiencing homelessness in particular. Further funding of harm reduction initiatives may help to engage more individuals experiencing homelessness with substance use treatment, potentially improving their health outcomes and ultimately cutting costs over time.

CITATIONS

Collins, S. E., Clifasefi, S. L., Nelson, L. A., Stanton, J., Goldstein, S. C., Taylor, E.M., . . . Jackson, T.R. (2019). Randomized controlled trial of harm reduction treatment for alcohol (HaRT-A) for people experiencing homelessness and alcohol use disorder. International Journal of Drug Policy, 67, 24-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.002