The reciprocal relationship between income and alcohol use for men in the United States

Education and income impact a variety of opportunities and decisions, including health behaviors, which can then in turn change the long-term course of someone’s life. This study detailed how yearly income influences alcohol use disorder symptoms and whether consequences of alcohol use influenced one’s later income. These study authors were especially interested in health disparities; that is, whether these patterns were different for people of different racial/ethnic identities.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

There are a variety of risk factors for alcohol use disorder (AUD) that if successfully targeted, would prevent individuals from experiencing it or its negative consequences. Socioeconomic status (SES) made up of income, level of education, and occupation, both influences alcohol use and is also influenced by alcohol use. There is wide variability in SES in the United States between different racial groups, with Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals being, on average, in lower SES groups than white individuals. In this study, Zemore and colleagues examined how SES, measured in this study by total yearly income, influences AUD symptoms and how that alcohol use in turn influences one’s SES. The study also explores whether there are different alcohol use and SES outcomes between four different racial/ethnic backgrounds (U.S.-born Hispanic or Latino, foreign-born Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White).

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

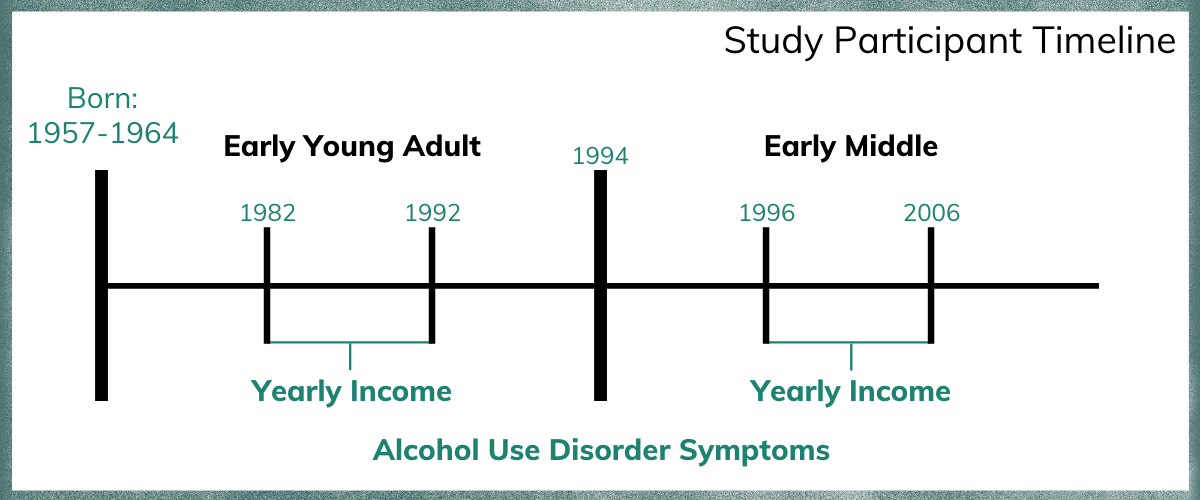

This study was a secondary analysis of longitudinal survey data from a study that followed over 6,000 individuals beginning in adolescence through middle adulthood (1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth). This study analyzed a subset of the dataset and focused on 3993 men who had participated in at least three survey waves. The authors examined whether income group during young adulthood (ages 21 to 31) predicted AUD symptoms at age 33, on average, and then whether these symptoms predicted income group during middle adulthood (ages 35 to 45), controlling for variables such as education and family history of alcohol problems.

Figure 1.

The primary variables in the analysis were the number of AUD criteria based on DSM-IV alcohol dependence (from 1-7 symptoms), their yearly income, and their race/ethnicity. The authors also used several control variables in the analysis to isolate the relationships between race/ethnicity, AUD symptoms, and income. These variables included age, adolescent poverty, educational attainment by 25 years old, marital and parenting status, history of alcohol problems in one’s biological family, early onset of regular drinking (drinking at least 1 to 2 times a month in the past year before age 15), and early heavy drinking (drinking 6 + drinks at least 4 to 5 times in the past month).

Of note, authors used a sophisticated statistical procedure to determine income group – which measured individuals’ income over time, with groups both for young adulthood – income from ages 21 to 31 – and middle adulthood – income from ages 35 to 45. Men during their early young adulthood years were grouped into four different yearly income trajectory groups: (1) individuals with income that started low and stayed persistently low, (2) individuals with low income that slowly increased during that time, (3) individuals with income in the middle class that stayed stable, and (4) individuals that experienced a rapid increase in income during those years. Men during their early midlife period were grouped into four different yearly income trajectory groups: (1) individuals with income that started low and stayed persistently low, (2) individuals with income in the middle class that stayed stable, (3) individuals with income in the upper middle class that stayed stable and (4) individuals with income in the high class that stayed stable.

Study participants were the 3993 men who had participated in at least three of the survey waves and who were part of one of five ethnic/racial groups: U.S.-born Hispanic or Latino (4.3%), foreign-born Hispanic or Latino (1.9%), non-Hispanic Black (13.6%), non-Hispanic White (63.6%).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Men from different racial groups have different numbers of AUD symptom criteria.

Black and U.S.-born Latino young adult men had significantly higher AUD symptom criteria count, compared to White men. White men, foreign-born Latino men, and men of other race/ethnicity had similar numbers of AUD criteria.

Men in the “persistently low” income group had several distinct characteristics, including more psychosocial challenges relative to other income groups.

Men in the persistently low income group were more likely to be Black or Hispanic/Latino (versus White), younger, have lower educational attainment (by age 25), be unmarried or separated/widowed/divorced (versus being married) in 1992, and be a parent of fewer or no children in 1992. Men in this persistently low income group were also more likely than those in the other groups to have started drinking earlier in life, a family history of alcohol problems, and reported more AUD symptom criteria in late young adulthood than all other groups.

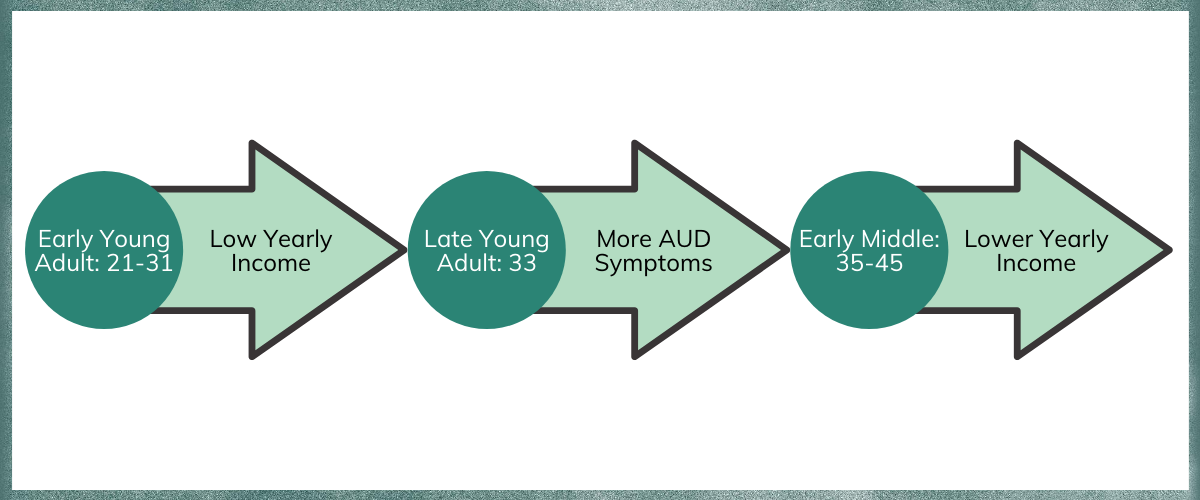

AUD criteria in late young adulthood resulted in worse income over time in later life independently of prior income.

Men with lower yearly income in early young adulthood had more AUD criteria in late young adulthood. When yearly income was accounted for, there were no longer any differences in the number of AUD criteria between Black and White men.

Men with a higher number of AUD criteria in late young adulthood were more likely to be in the persistently low yearly income group (versus the stable middle income group). These findings remained even when controlling for other characteristics that could explain the results, including education, history of alcohol problems, and marital status.

Figure 2.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study found that (1) early adulthood income predicts adult AUD, and, in turn, (2) adult AUD predicts middle adult income, and finally, (3) that SES explains in part why racial/ethnic minorities in the United States are more vulnerable to AUD. These findings point to the need for addressing recovery capital, i.e., resources for recovery, among individuals and patients with heavier alcohol use.

Figure 3.

SES, which is lower among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, is likely a marker for a group of psychological, social, and environmental factors which ultimately increase the risk of experiencing an AUD. For example, individuals with lower income likely have reduced access to health care, health foods, and community resources. The findings highlight that if lower-income individuals received interventions including linkages to services to help reduce the stress burden and instill optimism for a better future, they might experience reduced drinking harms and AUD. For example, public treatment programs could be further enhanced to more actively address job skills training or other factors related to financial resources, such as recovery-supportive housing. Additionally, screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) programs could be implemented more regularly among members of groups with lack of access to treatment and younger patients.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The analysis used data from a single birth group (cohort) and there may be something different about this group compared to other (earlier or later) birth groups.

- The study includes men only; findings may or may not generalize to women.

- AUD criteria was only measured at one point in time (1994) which may have missed earlier/later heavier use or recovery efforts.

- Racial/minority subgroups that were not large enough for analysis were grouped into an “other” racial category, potentially limiting our understanding of their income and alcohol use experience over time. Additionally, even some of the minority groups were comprised of relatively low numbers for this type of analysis.

- The authors made a series of choices in their analyses that may not hold up in future samples and which would decrease confidence in the real-world implications of their results. For example, the way different income groups were defined relied on several author decisions in determining those groups; if these decisions missed important factors then the reciprocal relationships between AUD and income may be inaccurate.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This study used survey data of men in the United States over time and found that yearly income and early education are associated with AUD in late young adulthood. Individuals with lower income and less education were more likely to experience worse AUD symptoms, compared to those with higher income and education. Income and education were also important independent of race/ethnicity, suggesting that these factors may be driving racial disparities in adult levels of AUD symptoms irrespective of race/ethnicity. Increasing one’s potential for employment and future yearly income such as through finishing education or undergoing skills training may also help reduce problematic alcohol use, which in turn may increase later income potential. It is plausible that for some individuals, greater education and good job skills and prospects may increase optimism and instill hope leading to more positive emotion and less likelihood of turning to alcohol as a stress reliever decreasing the chances of AUD symptoms over time.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This analysis of longitudinal survey data among men in the United States found that yearly income and early education are associated with greater numbers of AUD symptoms in late young adulthood; those with lower income and less education were more likely to experience more AUD symptoms. Income and education were also important independent of existing race/ethnicity, suggesting that these factors may be driving racial disparities in the level of AUD symptoms. Helping individuals increase their earning potential such as by connecting them to resources to allow them to finish school, attend college, or gain skills in a trade may confer benefits in terms of substance use treatment outcomes. It is plausible, for example, that for at least some individuals, greater education and good job skills and prospects may increase optimism and instill hope leading to more positive emotion and less likelihood of turning to alcohol as a stress reliever decreasing the chances of subsequent AUD symptoms over time. Treatments may benefit from an overall assessment of patient recovery capital, and further, a discussion that assesses career-related goals and working with clients to develop feedback-informed goals based on their aspirations. Discussing with patients their family structures to identify and refer potential early problematic drinking among children in the family may help to break a generational alcohol use cycle within the family.

- For scientists: This longitudinal analysis of cohort survey data among men in the United States found that yearly income and early education are associated with subsequent AUD symptoms in late young adulthood; those with lower income and less education were more likely to experience more AUD symptoms. Income and education were also important independent of existing race/ethnicity, suggesting that these factors may be driving racial disparities in the severity of AUD symptoms. Given that the process of achieving stable AUD recovery can involve many years, future research should examine AUD criteria at multiple points in time, rather than at a single point as this study did. Research should also address whether these factors are as strong in other birth cohorts or for other racial/ethnic minority groups. Finally, future research should explore whether providing direct access to recovery capital training activities (e.g., job skills training) helps to buffer the relationship between AUD and lifetime income.

- For policy makers: This analysis of longitudinal survey data among men in the United States found that yearly income and early education were associated with AUD symptoms in late young adulthood; those with lower income and less education were more likely to experience more AUD symptoms. Income and education were also important independent of existing race/ethnicity, suggesting that these factors may be driving racial disparities in the severity of AUD symptoms. Funding for early intervention and treatment, including educational/training supports, especially to reach children and adolescents in families with a history of drinking, may help to break a generational link of AUD. Additionally, it is plausible that greater community investment that enriches the lives of minority communities more generally could instill hope and optimism and reduce onset of AUD for these community members.

CITATIONS

Zemore, S. E., Lui, C., & Mulia, N. (2020). The downward spiral: socioeconomic causes and consequences of alcohol dependence among men in late young adulthood, and relations to racial/ethnic disparities. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(3), 669-678. doi: 10.1111/acer.14292