Can alcohol use disorder treatment help individuals reduce drinking and maintain these reductions over time?

There are many pathways to an improved life for individuals with alcohol use disorder. While some may choose abstinence as their treatment goal, others may prefer to reduce their drinking without quitting entirely. In this study, authors showed that for at least some individuals receiving state-of-the-art behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorder, reductions in drinking are associated with other health improvements, and can be maintained over time.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Given that many individuals who seek alcohol use disorder treatment would prefer to reduce rather than quit drinking entirely, research that answers the question of whether reduced drinking is an achievable and sustainable treatment goal is key to engaging as many individuals with alcohol use disorder as possible in treatment and recovery support services – emphasizing abstinence only may be a barrier to individuals seeking treatment. The primary concerns with drinking reduction treatment goals, rather than abstinence, are that such reductions will be difficult for many individuals with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder to maintain over time, and that difficulties with maintaining such gains could result in life altering negative consequences. Nevertheless, evidence from previous studies has suggested that drinking reductions may be both achievable and sustainable as treatment endpoints for some, though there are key lingering empirical questions about the extent to which the findings from those studies apply to individuals with more severe variants of alcohol use disorder. In this study, researchers sought to extend what was previously known about the subject of low-risk drinking in alcohol use disorder by assessing whether the prevalence, functional outcomes, and maintenance of drinking reductions were replicated between groups of individuals with alcohol use disorder in two rigorous studies of behavioral treatments.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

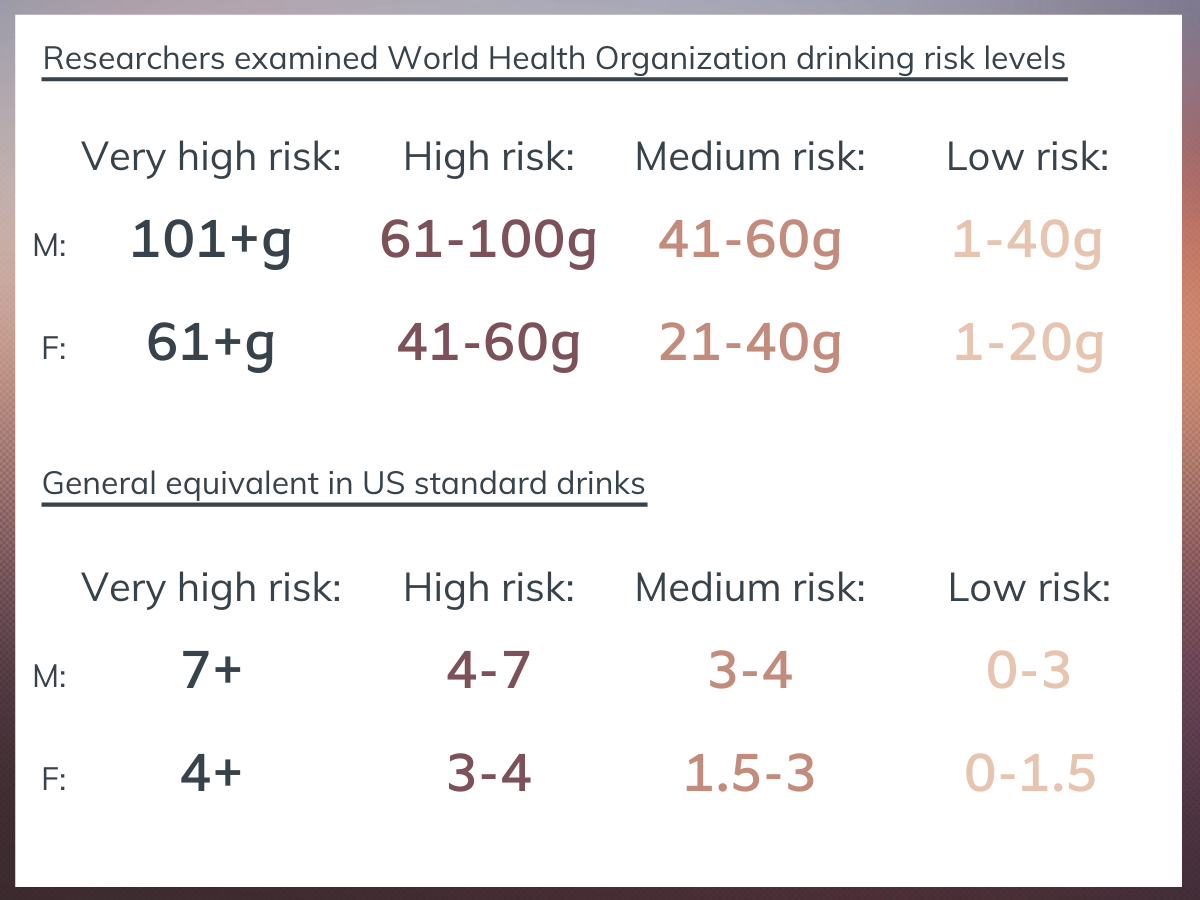

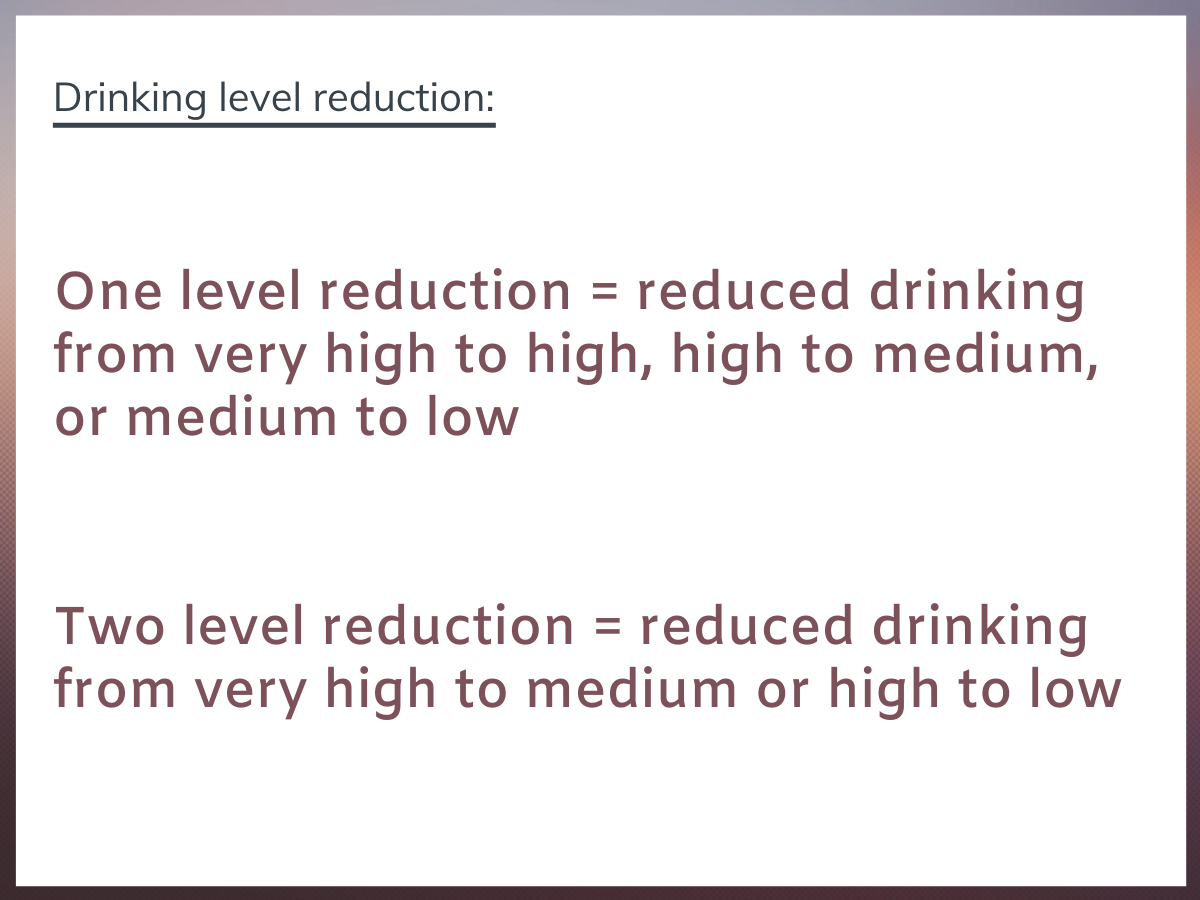

This study was a secondary data analysis of two large randomized trials for alcohol use disorder treatments, which tested whether drinking reductions (based on World Health Organization [WHO] risk categories) at the end of treatment were associated with improved functioning and were maintained out to the 1-year follow-up point. One sample was derived from the United States (US) Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence, better known as COMBINE, which randomized 1,383 US participants with alcohol use disorder to several combinations of medication and behavioral treatment. The second study was the United Kingdom (UK) Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT), which randomized 742 U.K. participants with alcohol use disorder to one of two psychosocial treatments. Combining these two datasets, the authors examined whether achieving at least 1- and 2-level reductions in WHO risk levels in the last month of treatment was associated with liver enzyme concentrations, alcohol-related consequences, and mental health at the end of treatment, and whether any improvements held equally for individuals irrespective of their drinking severity. In order to determine whether their findings would apply just to those who reduced drinking, rather than entirely abstaining, the authors conducted the same set of analyses without abstainers.

Figure 1. There are 14 grams of ethanol in a standard US drink, but the amount of alcohol in a “standard drink” varies internationally (e.g., 8 g in the UK; 20 g in Austria).

The authors calculated WHO risk levels for all study participants based on average amount of alcohol consumed per day over a period of one month. Risk levels were assessed at one month prior to receiving treatment (i.e., baseline), 1 month prior to the end of treatment (i.e., month 4 in COMBINE and month 3 in UKATT), and 1 year following the end of treatment (COMBINE) or treatment entry (UKATT). Alcohol dependence severity was assessed in the COMBINE study via the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4) and in the UKATT study via the Alcohol Dependence Scale and the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire. Both studies also collected data related to other measures of health and well-being (i.e., liver enzymes, mental health, alcohol-related consequences).

Figure 2.

Although most of the individuals in both studies were in the very high-risk level (i.e., greater than 3 drinks at 40% alcohol), and none were abstinent, by the last month of treatment and at the 1-year follow-up point, most were in the abstinent, low (i.e., around 1 drink at 40% alcohol), or medium (i.e., greater than one and less than two drinks at 40% alcohol) risk levels.

Most of the individuals from both studies were white males, who either met the criteria for alcohol dependence (COMBINE) or were otherwise seeking treatment for alcohol related issues (UKATT). On average, the participants from the COMBINE study were 44 years old, 77% white and 69% male. For the UKATT study, participants were an average of 42 years old, 74% male and 96% white. None of the participants from either study met the diagnostic criteria for comorbid psychiatric conditions, including other substance use disorders.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Reductions in WHO risk levels were generally associated with improved functioning.

In both treatment samples, WHO risk level reductions of at least 1- and 2-levels were associated with significantly lower liver enzyme levels, improvements in mental health, and reductions in alcohol-related consequences. Moreover, the greater improvements in these measures of functioning were detected among those with the higher alcohol dependence severity.

Reductions in WHO risk levels were generally sustained by the 1-year follow-up point.

Many of the observed risk level reductions seemed to be sustainable. In fact, most who achieved at least a 1- or 2-level reduction in WHO risk level had maintained their progress by the 1-year follow-up point. In the COMBINE study, of those with a 1-level reduction in WHO risk at the end of treatment, 88.1% of the mild alcohol dependence group, 85% of the moderate alcohol dependence group, and 85.6% of the severe alcohol dependence group maintained this reduction out to the 1-year follow-up. Of those with a 2-level reduction in WHO risk at the end of treatment, 80.5% of the mild, 77.4% of the moderate, and 77% of the severe maintained at least a two-level reduction at the 1-year follow-up. In the UKATT, 79% of the mild alcohol dependence group, 80% of the moderate alcohol dependence group, and 79.3% of the severe alcohol dependence group maintained at least a one-level reduction at 1-year, whereas 69.1% of the mild, 68.8% of the moderate, and 71.1% of the severe maintained at least a two-level reduction at the 1-year follow-up. When controlling other variables (i.e., age and sex) to isolate the sustainability of WHO risk level reduction over time, individuals with a 1- or 2-level reduction by the end of treatment had more than 3.2 and 2.6 times greater likelihood of maintaining this drinking reduction, compared to slipping back to more severe drinking levels, at the 1-year follow-up in the COMBINE and UKATT studies, respectively.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

The findings of this study support the idea that drinking reductions may be an achievable and sustainable treatment goal, even among some individuals with more severe alcohol use disorder. Similar findings have come from previous work conducted by this research group, using data from the Project MATCH study. In that study, a group of individuals with some instances of heavy drinking (4+ drinks for women, or 6+ for men in 1 day) experienced psychosocial improvements. Indeed, as shown also in nationally-representative studies of US adults in remission from alcohol use disorder, such bouts of heavy drinking don’t necessarily jeopardize remission status or progress. Taken together, these collective findings provide good news, especially for those individuals with alcohol use disorder who generally would prefer a drinking reduction goal, are having a difficult time maintaining abstinence despite their best efforts, or may otherwise not yet be ready to entirely abstain from alcohol, and, therefore, engage in abstinence-based treatment. These findings are also helpful for treatment providers who employ a patient-centered, harm reduction approach to treatment that can include goals to reduce drinking. Given the potential individual and public health benefits of reducing treatment barriers, treatment goals and processes should certainly be broadened to include behavior change beyond entire abstinence so as to attract as many individuals with alcohol use disorder as possible.

While supporting the viability of drinking reductions as a health-promoting treatment goal for those who prefer it, there are many reasons why abstinence should be encouraged. First, alcohol is a known Group 1 carcinogen (similar to asbestos and tobacco smoke, it is causally related to cancer), potential cause of liver disease, and a neurotoxin (it has a degenerative/damaging effect on brain tissue and corresponding cognitive, emotional, and motor functioning). Hence, exposure to alcohol even in relatively small amounts carries with it an increased risk of adverse health consequences, and in increasing amounts, increases risks of intoxication-related accidents and increased likelihood to develop addiction and/or become addictively re-involved with alcohol. Moreover, the authors reported that, while significant improvements were associated with drinking reductions, abstinence was ultimately associated with the best outcomes – a finding that is confirmed by other studies as well.

Given that abstinence is associated with the most optimal outcomes and alcohol can be harmful via toxicity and intoxication, as well as alcohol use disorder, educating patients about these risks and outcomes while allowing for different drinking goals may be the best approach for engaging more individuals in a salutary alcohol use change process and thereby begin to reduce overall global health harms. By engaging individuals with any drinking goal, ranging from abstinence to ongoing drinking with attention to reduce health harms, treatment and recovery support systems can engage the maximum number of individuals with alcohol use disorder, and ultimately improve alcohol-related public health.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Questions concerning the degree to which the findings from this study might apply to all individuals with alcohol use disorder emerge in light of the fact that participants in both the COMBINE and UKATT were predominantly white males seeking outpatient treatment and both studies excluded individuals with severe co-occurring psychiatric disorders and co-occurring substance use disorders.

- Participants in both studies had a mix of abstinence and drinking reduction goals. Because some participants may have intended to abstain, but only managed to reduce drinking, or vice versa, questions arise concerning the influence of these intentions on the outcomes observed.

- Outcomes were only measured out to 1-year post-treatment. Other research has shown that measures of subjective well-being can improve in the first year of recovery and change direction subsequently, before stabilizing through the emergence of long-term recovery (after 5 years).

- While not a limitation of the study, per se, part of the “debate” on the viability of reduced drinking as an alcohol use disorder treatment goal are anecdotal concerns regarding life-altering consequences for those who attempt, but cannot maintain, drinking reductions. This study did not compare the severity of unsuccessful outcomes for those who had reduced their drinking during treatment compared to those who abstained.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This secondary data analysis of multisite clinical trials from the UK and US with more than 2,000 alcohol use disorder participants showed that moderate use of alcohol, as represented by reductions in WHO risk levels, is a viable treatment goal for some individuals with alcohol use disorder. Importantly, risk level reductions were associated with improvements in functional outcomes, including liver enzymes, alcohol-related consequences, and mental health, and many of these improvements persisted up to one year following treatment. The findings from this study may appeal to a certain type of individual seeking help, namely, those who are having a difficult time abstaining or those who wish to reduce their drinking, rather than giving up drinking entirely. For these individuals, incremental improvements in health and well-being can be experienced as a result of cutting back. Importantly, the implications for individuals and families seeking recovery is that, while abstinence is still associated with the greatest overall recovery-related benefits, drinking reductions are also associated with positive health changes, and, on average, appear to be maintained over time. So, encouraging any alcohol use reduction is beneficial to health with abstinence being associated with the best outcomes.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This secondary data analysis of multisite clinical trials from the UK and US with more than 2,000 alcohol use disorder participants showed that moderate use of alcohol, as represented by reductions in WHO risk levels, is a viable treatment goal for some individuals with alcohol use disorder. Importantly, risk level reductions were associated with improvements in functional outcomes, including liver enzymes, alcohol-related consequences, and mental health, and many of these improvements persisted up to one year following treatment. The findings from this study may be especially helpful for treatment providers who implement a patient-centered, harm reduction approach. These findings may also inform providers whose patients are having difficulty sustaining abstinence, despite their best efforts. Specifically, providers can use these findings to reframe conversations with their patients in terms of what types of changes constitute successful health outcomes. Notwithstanding these benefits, given that abstinence is associated with the most optimal outcomes and alcohol can be harmful via toxicity and intoxication, as well as alcohol use disorder, educating patients about these risks and outcomes while allowing for different drinking goals may be the best approach for engaging more individuals in a salutary alcohol use change process and thereby begin to reduce overall global health harms.

- For scientists: This secondary data analysis of multisite clinical trials from the UK and US with more than 2,000 alcohol use disorder participants showed that moderate use of alcohol, as represented by reductions in WHO risk levels, is a viable treatment goal for some individuals with alcohol use disorder. Importantly, risk level reductions were associated with improvements in functional outcomes, including liver enzymes, alcohol-related consequences, and mental health, and many of these improvements persisted up to one year following treatment. Although abstinence is more convenient as a behavioral proxy for recovery in terms of the quantitative precision that it offers, it is becoming clearer that this behavior change does not always accurately capture the phenomenon scientists are aiming to describe. The findings of this study support the long-held view that recovery should be conceptualized and measured both as changes in addictive behavior as well as corresponding measures of health and subjective well-being. Generally, recovery research is more likely to reflect the subjective experiences of individuals who identify as being in recovery including measures of functional improvement associated with reductions of addictive involvement, particularly over longer durations of time.

- For policy makers: This secondary data analysis of multisite clinical trials from the UK and US with more than 2,000 alcohol use disorder participants showed that moderate use of alcohol, as represented by reductions in WHO risk levels, is a viable treatment goal for some individuals with alcohol use disorder. Importantly, risk level reductions were associated with improvements in functional outcomes, including liver enzymes, alcohol-related consequences, and mental health, and many of these improvements persisted up to one year following treatment. The findings from this study may warrant the funding of future research to best identify who in particular may be able to successfully reduce their drinking in response to treatment and experience positive health behavior change. Moreover, these findings may inspire policy makers to work with relevant stakeholder groups to develop messages that balance the recommendation of abstinence with a patient-centered, harm reduction approach to engage as many individuals as possible in the process of recovery.

CITATIONS

Witkiewitz, K., Heather, N., Falk, D. E., Litten, R. Z., Hasin, D. S., Kranzler, H. R., Mann, K. F., O’Malley, S. S., & Anton, R. F. (2020). World Health Organization risk drinking level reductions are associated with improved functioning and are sustained among patients with mild, moderate and severe alcohol dependence in clinical trials in the United States and United Kingdom. Addiction, 115(9), 1668-1680. doi: 10.1111/add.15011