Using emergency department visits to actively link patients with alcohol use disorder to specialty addiction treatment

Hospital emergency departments (EDs) must contend with some of the most severe elements of alcohol use disorder. On top of treating alcohol-related consequences, EDs often bear the greatest financial burdens associated with alcohol use disorder. The situation is compounded by the recidivism observed among affected patients due to ineffective or absent treatment for their alcohol use disorder. In this study, findings showed that individuals who received enhanced treatment for alcohol use disorder experienced reduced ED utilization and drinking as well as improvements in mental health.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

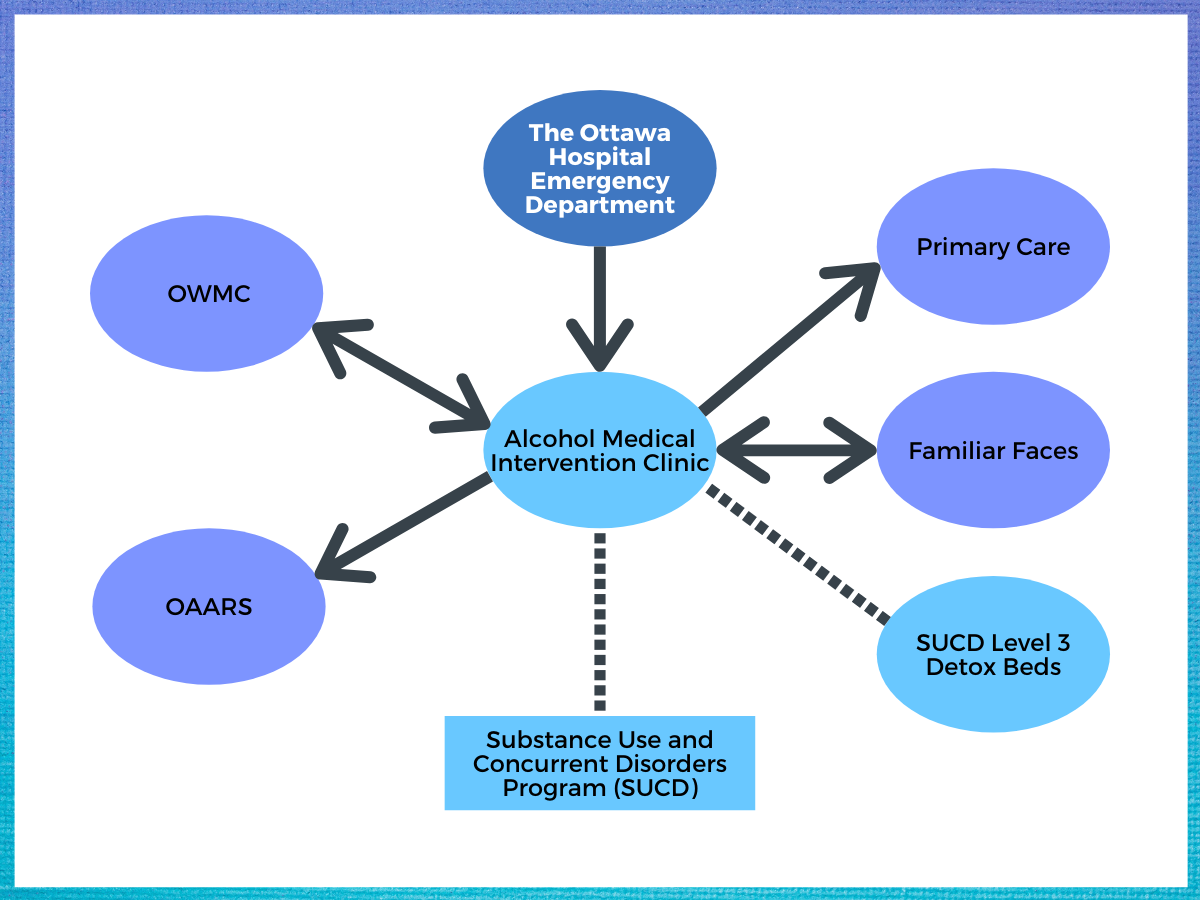

In the United States (US), alcohol use disorder is associated with ever-increasing rates of morbidity and mortality. Alcohol-related deaths in the US have risen steadily over the past several decades and now exceed 95,000 annually. This trend appears to be consistent cross-nationally, as well. In recent years, Canada has also observed a significant uptick in alcohol-related deaths and other negative health consequences, which has resulted in a costly burden on the nation’s Emergency Department (ED) systems. To address this growing problem, a novel treatment program was created at the Ottawa Hospital, called the Alcohol Medical Intervention Clinic (AMIC). The expressed objective of the intervention was to reduce the burden on the Hospital’s ED through the provision of withdrawal management services to patients who were either admitted for alcohol-related reasons, were experiencing withdrawal, or at risk of experiencing withdrawal. Treatment services offered by the intervention included assessment, triage, and transition to/navigation of appropriate levels of care both in and outside of the Hospital. The authors objective in this study was to observe changes for individuals referred from the ED to the intervention program in terms of reduced ED utilization in addition to reduce alcohol use and mental health symptoms, such as anxiety and depression.

Figure 1. Alcohol Medical Intervention Clinical (AMIC) Collaborations. Abbreviations: OWMC = Ottawa Withdrawal Management Centre; OAARS = Ottawa Addicts Access and Referral Services.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was an observation pre-post single-group study involving 194 patients examining an ED-based treatment protocol for alcohol use disorder. Although 248 patients were initially qualified for participation in the study, only 194 completed informed consent and were ultimately included. Because the authors primarily were interested in assessing the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing alcohol-related ED utilization, they calculated the number of alcohol-related visits and revisits to the ED for each patient during the 30 days before and after receiving treatment services through chart reviews. To get a sense of the broader impact the intervention was having in this regard, the authors also compared the total number of alcohol-related ED visits from the 12 months before the intervention to the 12-month period following the intervention. Their secondary interest was the effectiveness of intervention in terms of reducing alcohol use and mental health symptoms among the involved patients. To determine this relationship, they compared the scores from several measures that they collected upon initiation to scores from similar measures collected by phone 30 days following the intervention. In addition to demographics, these measures included self-report of severity of alcohol dependence and harmful drinking, past 30-day substance use and severity of substance use, and depression and anxiety symptoms. A final metric of the program’s effectiveness included patient satisfaction with the treatment received within the intervention and connections made to community treatment resources.

In general, the patients that were included in this study tended to be white (83.7%), college-educated (52.4%) males (64.9%). At the beginning of the study (initiation of intervention services), all of the patients were either experiencing withdrawal from alcohol, at risk of experiencing withdrawal, or otherwise referred to the intervention services by an ED provider for alcohol-related reasons. The average age of patients was 42.4 years. Those that participated in the follow-up portion of the study (78% of the initial sample), tended to possess more favorable prognostic characteristics being significantly older, reporting significantly less crime and violence problems, and were less involved with other drugs, including cocaine and cannabis.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Individuals who received enhanced treatment for alcohol use disorders experienced reduced utilization of Emergency Departments.

In terms of the impact that intervention services had on the Hospital ED system, the authors found that there was an 82% reduction in alcohol-related ED visits among the patients involved in the study throughout the 30 days following discharge from the intervention. Further, among the patients who had been admitted to the ED in the 30 days prior to beginning the Alcohol Medical Intervention Clinical (AMIC), there was a 71% reduction in alcohol-related ED visits. For the total number of alcohol-related ED visits throughout the 12-month periods before and after the intervention, there was an 8.1% reduction in alcohol-related ED visits, and there was a 10% reduction in the total number of alcohol-related ED visits 30 days following the intervention.

Individuals who received enhanced treatment for alcohol use disorders experienced improved early alcohol-related and mental health outcomes following discharge from Emergency Departments.

In terms of the change in participants’ alcohol use and mental health outcomes, patients receiving services reported significantly fewer instances of alcohol use from intake to the 30-day follow-up point, as well as a decrease in hazardous and harmful drinking. These patients also reported significant decreases in mental health symptoms (i.e., less depression and anxiety symptoms) following the intervention services.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Consistent with the findings from other research on ED-based addiction-related care, this intervention study found that enhanced alcohol withdrawal treatment services can not only reduce the alcohol-related financial burden on EDs; they can also improve alcohol use outcomes and mental health symptoms among affected individuals, at least during the earliest phases of recovery. It should be noted, however, that the single-group study design (lack of treatment-as-usual or other comparison condition) prevents the attribution of apparent changes directly to intervention effects.

There are important economic and treatment/recovery-related implications of this study. First, in terms of its economic implications, the findings from this study suggest that the long-term financial burden on the healthcare system, imposed by alcohol use disorder and associated consequences, might be mitigated through an upfront investment of resources aimed at early detection and intervention for alcohol-related problems. Such findings reinforce the view that addiction is, in part, a systemic problem that can be addressed usefully at various levels of multiple systems, including the healthcare system.

Next, the findings from this study support what has been revealed through other previous studies concerning the important downstream recovery-related effects of early interventions for alcohol use disorder. The earlier the detection and intervention, the better the chances of a long-term, stable recovery trajectory. Given the fact that alcohol consumption of any amount increases the likelihood of accidents and other serious health-related consequences, it is not surprising that those with alcohol use disorder, of varying severity, tend to require emergency-based services more frequently than the aggregate population. Additionally, the types of events that bring individuals to EDs tend to be laden with emotional and motivational relevance, such that experiences within the ED that are attributable to alcohol use potentially offer a critical therapeutic opportunity, if leveraged effectively.

Lastly, this study measured recovery-related success in terms of reductions in harmful and hazardous drinking during the 30 days following intervention. Future research may help to determine whether and to what extent such outcomes are sustainable over longer periods of time and whether such outcomes are associated with improvements in other aspects of individuals’ lives, such as interpersonal relationships and subjective well-being.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The study design had no comparison condition with which to compare the intervention’s effects, so we cannot say with confidence that the intervention caused the observed improvements in patients’ alcohol use and functioning. This limitation is emphasized by the fact that only 46% of the initial participants completed the follow-up surveys.

- There are questions concerning the extent to which the findings from this study might be generalizable to other EDs and other individuals receiving ED-based treatment for alcohol-related problems given the fact that the intervention program was offered within the context of a primarily state-sponsored urban hospital. Moreover, most of the AMIC patients were white, college-educated males. Therefore, it remains unclear whether a similar treatment program would work as effectively in a more rural setting, among individuals with less available recovery capital, and/or within a predominantly privatized healthcare system, where different insurance mechanisms come to bear upon treatment coverage.

- The reported effectiveness of the intervention was based on the outcome that was measured among the participating patients. However, only about 60% of the individuals that were originally referred to the intervention presented for treatment or participated in the study. While the authors suggested possible factors, such as systematic barriers deterring access (e.g., hours of operation, transportation limitations, etc.), the question of why these individuals did not present for treatment remains relevant to ultimately explaining the relative effectiveness of this program.

- It is unknown whether the patients receiving intervention services through the Ottawa Hospital presented for care at any other hospital, outside of that system, during the period of assessment.

BOTTOM LINE

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: This intervention study consisting of nearly 200 patients who presented to the emergency department with alcohol-related medical conditions, including withdrawal symptoms, showed that those receiving linkages to comprehensive, specialty treatment had reductions in emergency department visits, as well as reduced harmful drinking and improved mental health. While the study, given its design and limitations, does not necessarily suggest the intervention caused the improved outcomes, this innovative model is worthy of future, more rigorous research to determine if it helps patients while reducing costs. Individuals and family members seeking recovery who receive services from emergency departments may benefit from asking staff about linkages to treatment and recovery support services in the community.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: This intervention study consisting of nearly 200 patients who presented to the emergency department with alcohol-related medical conditions, including withdrawal symptoms, showed that those receiving linkages to comprehensive, specialty treatment had reductions in emergency department visits, as well as reduced harmful drinking and improved mental health. While the study, given its design and limitations, does not necessarily suggest the intervention caused the improved outcomes, this innovative model is worthy of future, more rigorous research to determine if it helps patients while reducing costs. The findings from this study are of particular relevance to treatment professionals and treatment systems. A central reason for the effectiveness of this intervention was interpreted by the authors to be the seamless integration of the intervention program with other community resources. Therefore, there is good reason for community-based treatment providers and systems to seek out connections with hospital-based services to provide an effective continuum of care for affected individuals.

- For scientists: This intervention study consisting of nearly 200 patients who presented to the emergency department with alcohol-related medical conditions, including withdrawal symptoms, showed that those receiving linkages to comprehensive, specialty treatment had reductions in emergency department visits, as well as reduced harmful drinking and improved mental health. While the study, given its design and limitations, does not necessarily suggest the intervention caused the improved outcomes, this innovative model is worthy of future, more rigorous research to determine if it helps patients while reducing costs. There is mounting evidence that providing enhanced services for the treatment of substance use disorders within the context of emergency care can improve the trajectory of recovery. However, more research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms by which these services produce their salutary benefit. Comparative studies are needed to determine whether and to what extent healthcare funding mechanisms influence the outcomes of these services. It is also important to better understand the effect such services have on long-term (greater than five years) recovery. Future research is also needed to determine whether such services would likely improve the treatment outcomes for individuals suffering from other substance use disorders, such as opioid use disorder.

- For policy makers: This intervention study consisting of nearly 200 patients who presented to the emergency department with alcohol-related medical conditions, including withdrawal symptoms, showed that those receiving linkages to comprehensive, specialty treatment had reductions in emergency department visits, as well as reduced harmful drinking and improved mental health. While the study, given its design and limitations, does not necessarily suggest the intervention caused the improved outcomes, this innovative model is worthy of future, more rigorous research to determine if it helps patients while reducing costs. The findings from this study may warrant funding future research to best identify which types of individuals would be most responsive to the type of treatment described in this study. Moreover, these findings may inspire policy makers to work with relevant stakeholder groups to develop messages that balance recommendations of prevention with the recommendation of ED-based treatment services to engage as many individuals as possible in the process of recovery.

CITATIONS

Corace, K., Willows, M., Schubert, N., Overington, L., Mattingly, S., Clark, E., . . . Hebert, G. (2020). Alcohol medical intervention clinic: A rapid access addiction medicine model reduces emergency department visits. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 14(2), 163-171. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000559.