A statewide policy may help increase delivery of post-overdose services in emergency departments, but barriers remain

Critical locations have been identified to deliver services that can reduce substance-related disease and premature death. One of these places is the emergency department, with this setting becoming especially important given that opioid overdose deaths continue to increase in the United States and most individuals with opioid use disorder do not receive treatment. In this study, researchers interviewed emergency department staff to evaluate a statewide policy in Rhode Island that aimed to standardize services delivered to opioid overdose survivors in the emergency department.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Given that only a subset of individuals with opioid use disorder engage with treatment, opportunities to identify individuals at high risk of opioid overdose death, also known as touchpoints, have emerged to increase the delivery of evidence-based treatment and harm reduction services. Some of these touchpoints include release from incarceration, hospitalization for an injection-related infection, and an emergency department visit for a nonfatal overdose.

Many individuals with opioid use disorder are likely to interact with hospital emergency departments. In the past, the standard of care for treating patients with opioid use disorder in the emergency department has been providing a referral to outpatient addiction treatment, yet this referral is generally not sufficient to successfully link patients with medication treatment or related services.

Recently, some emergency departments have leveraged opioid-related visits as an opportunity to deliver interventions aimed at reducing opioid-related morbidity and mortality. Examples include emergency department-initiated buprenorphine, embedding peer support specialists within the department, and overdose education and naloxone distribution programs.

In 2017, Rhode Island implemented a statewide policy across all emergency departments and hospitals in the state that requires they have protocols and written policies to deliver a minimal standard of care for patients with opioid use disorder. In this study, researchers conducted interviews with senior management and clinical staff at emergency departments in Rhode Island to evaluate the implementation of this statewide policy. Findings from this study help identify barriers and facilitators that impact the delivery of services to patients with opioid use disorder in the emergency department and inform future implementation of these models in other locations.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a qualitative study where researchers conducted 55 individual interviews with senior management and clinical staff at five emergency departments in Rhode Island to understand the implementation of a new statewide policy that aimed to increase the delivery of services to individuals with opioid use disorder. The interviews focused on assessing gaps and best practices for care delivery which allowed researchers to identify barriers and facilitators. The interviews were conducted from November 2019 to July 2020 and were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed for themes.

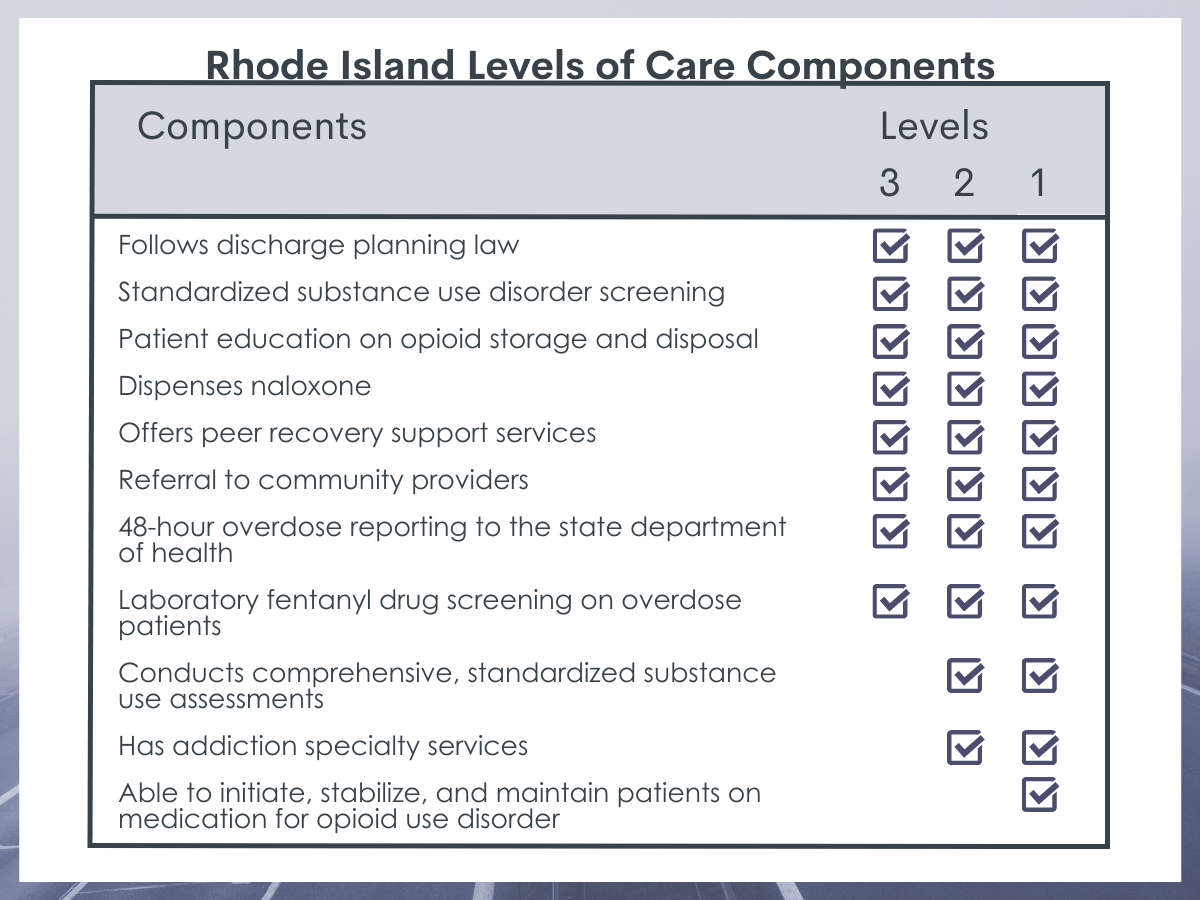

The Levels of Care for Rhode Island is a statewide policy for treating overdose and opioid use disorder in all of Rhode Island’s emergency departments and hospitals. The main goal of the policy is to standardize person-centered, evidence-based care of patients with opioid use disorder across all of the state’s emergency and hospital institutions. The policy aims to improve care provided to adult patients with opioid use disorder, prevent opioid overdose deaths, increase linkage to treatment, and improve the timeliness of overdose surveillance. There are three levels of care with the minimal expectation that all facilities would at least meet Level 3 criteria. The components of each level of care are in the table below:

Study participants were intentionally enrolled to represent senior management and clinical staff at all nine emergency departments in Rhode Island. Participants were recruited by poster advertisements and emails. They were financially incentivized to participate through a $50 gift card honorarium. Staff from only five of the nine emergency departments in Rhode Island participated in the interviews due to effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff availability and limited staff in smaller and remote emergency departments. Interviews were done either in-person or by telephone, based on the preference of the study participant, before the pandemic and, after February 2020, were done by telephone. The interviews lasted an average of 40 minutes.

A total of 55 study participants were interviewed including 17 senior management and 38 clinical staff (4 attending physicians, 15 residents, 6 physician assistants, and 13 nurses). Demographics were not collected due to small sample size to ensure confidentiality. Of the five emergency departments represented in the study, four had Level 1 designation and one had Level 3 designation.

The interviews were facilitated using a topic guide that was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and explored the implementation of post-overdose policies within emergency departments, strengths and weaknesses in care delivery, resources offered, and training needs. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research is comprised of five domains: intervention characteristics, inner setting, external setting, individuals’ characteristics, and implementation process. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, and the qualitative data from the interviews was coded with statistical software and analyzed for themes.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Standardization and the use of peers helped support post-overdose service delivery in the emergency department.

Participants described a standardized approach to post-overdose service delivery as critical to improving uptake and quality. This standardized approach seemed to be most adaptable to naloxone distribution, where it was highlighted that maintaining a stock of naloxone in the emergency department was critical to providing patient access. An “opt out” approach was identified as a facilitator to uptake (i.e., linking individuals to outpatient treatment without their direct consent), although some participants endorsed providing services without informed consent, potentially reducing patient autonomy.

Peer support specialists, also known as recovery coaches, were consistently seen by study participants as an integral component of post-overdose service delivery. These individuals are on-call to provide non-clinical support to patients, including linkage to treatment and other community services. Leveraging lived experience with addiction was identified as a unique tool that facilitated meaningful interactions with patients, ongoing support after the emergency department visit, and connection to outpatient care.

Social and structural barriers were identified as barriers to post-overdose service delivery in the emergency department.

Study participants emphasized that social-structural factors intersected with post-overdose care delivery. Housing instability, lack of health insurance, unemployment, and language barriers were identified as impeding the effectiveness of service delivery. These factors were compounded by the lack of availability of and insurance requirements for treatment beds, which resulted in many patients being kept in the emergency department for days waiting for a treatment bed to become available or patients not being eligible for treatment beds at all.

There are many barriers to initiation of medications for opioid use disorder in the emergency department.

Study participants reported that patients were not able to readily access medication treatment in the emergency department due to a variety of challenges, despite many providers being certified (i.e., “waivered”) to initiate medications such as buprenorphine. These challenges included participants not seeing the initiation of medications for opioid use disorder as the role of emergency departments, uncertainty around the benefits of these medications, the barrier of finding additional time to do the waiver training to prescribe buprenorphine, lack of knowledge around prescribing these medications and the fear of precipitating opioid withdrawal, and challenges with connecting patients to medication providers in the community.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study conducted interviews with senior management and clinical staff to evaluate a statewide policy in Rhode Island aimed to standardize services delivered to opioid overdose survivors in the emergency department. Findings of the study document key facilitators and barriers that impacted the delivery and quality of these services. Standardization and the use of peers were seen as facilitators to post-overdose services while social-structural factors (housing, employment) were identified as barriers. Medications for opioid use disorder were rarely initiated due to multiple identified challenges.

Opportunities to identify individuals at high risk of opioid overdose death, also known as touchpoints, have emerged to increase the delivery of evidence-based treatment and harm reduction services. Some of these touchpoints include release from incarceration, hospitalization for an injection-related infection, and an emergency department visit for a nonfatal overdose. This latter group is especially vulnerable to subsequent opioid-related harm. One study estimated that 20% of Medicaid beneficiaries who experienced an overdose experienced another within 1 year, and another study showed that 5.5% of individuals who experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose had died one year later. Findings from this study highlight facilitators and barriers to implementing interventions in the emergency department targeting this high-risk population. For example, standardizing the distribution of naloxone, utilizing peers, ensuring a smooth transition to treatment in the community, and consideration of the special needs of this population were all identified as potential modifiable facilitators to delivering services.

Participants noted that peer support specialists, also known as recovery coaches, were consistently seen as an integral component of post-overdose service delivery in the emergency department. Evidence is emerging for the unique skill set of peers to improve patient outcomes. Utilizing peers in general hospital settings, in emergency departments, and to actively link individuals to treatment in the community have shown promise but require more rigorous scientific investigation.

Despite a strong evidence base, medications for opioid use disorder were rarely initiated in the emergency department. While some cited the 8-hour training required to receive a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, many participants did not see this as the role of emergency departments, instead preferring to refer to medication treatment in the community. This finding underscores that, while a recent policy change was made to expand access to buprenorphine by not requiring the waiver training for providers, significant barriers to initiating buprenorphine treatment in the emergency department remain.

Other interviewees highlighted lack of training, uncertain effectiveness, and lack of infrastructure to deliver medications for opioid use disorder in the community as barriers. Research has shown that emergency departments are an appropriate setting to initiate medications for opioid use disorder, although timely community-based follow up is critical to treatment retention. Utilizing peers may help facilitate initiating medications for opioid use disorder in the emergency department and ensuring a smooth transition to the next level of care. In addition, expanding provider education on the benefits of medications for opioid use disorder, ensuring timely access to continuing medication treatment beyond the emergency departments, and developing dedicated teams to support patients with opioid use disorder in the emergency department can help overcome barriers identified in this study.

Findings from this study highlight key questions about the quality of care that patients with opioid use disorder receive in the emergency department. Some interventions, such as naloxone distribution or referral to outpatient treatment, were delivered without informed consent from the patient, undermining the individual’s autonomy. Many patients who experienced an opioid overdose arrived at the emergency department stable after receiving naloxone in the field and faced lengthy wait times, and others stayed in the emergency department for days waiting to be connected to treatment. Also, patients were often perceived as posing a risk to themselves or others and were dispossessed of their belongings. These patient experiences of mistreatment and stigma might reduce the likelihood that they will engage in services in the emergency department and subsequently seek medical care.

The study’s findings were in the context of a statewide policy for treating overdose and opioid use disorder in all of Rhode Island’s emergency departments and hospitals. Currently, there are 14 state policies mandating that certain services be delivered to individuals with substance use disorders in the emergency department, ranging from requiring screenings to making medications available. These types of state policies may be promising in standardizing services available to individuals with substance use disorders presenting to the emergency department and helping to overcome the many barriers to treating these individuals in this setting.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- This qualitative study included interviews with individuals in only a subset of emergency departments in Rhode Island. In addition, the findings of this study were in the context of a state policy mandating that emergency departments and hospitals have an organizational plan and structure to treat opioid use disorder and opioid overdose. Generalizing these findings to other emergency departments in other states should be done with caution.

- Even though peers were identified as critical to emergency department post-overdose response interventions, they were not included in the interviews. In addition, perspectives of the patients were also not included.

- This study only qualitatively assessed barriers and facilitators to post-overdose response interventions delivered in the emergency department. Patient outcomes, such as utilization of these interventions, should be assessed in future studies.

BOTTOM LINE

This study conducted interviews with senior management and clinical staff to evaluate a statewide policy in Rhode Island aimed to standardize services delivered to opioid overdose survivors in the emergency department. Findings of the study document key facilitators and barriers that impacted the delivery and quality of these services. Standardization and the use of peer recovery support specialists were seen as facilitators to post-overdose services while social-structural factors such as unstable housing and employment challenges were identified as barriers. Medications for opioid use disorder were rarely initiated.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The emergency department may be an opportune setting for individuals with opioid use disorder to receive or be connected to evidence-based services. Individuals who have experienced an opioid overdose may be especially willing to engage in these services. Initiating medications for opioid use disorder in the emergency department, such as buprenorphine (often prescribed in formulation with naloxone and known by the brand name Suboxone), and then continuing treatment in the community may be a better option to increase engagement in treatment than simply providing a referral to treatment. Harm reduction services, such as being educated on the signs of an overdose and having naloxone available, are important components to the continuum of care for opioid use disorder, given its oftentimes chronic nature.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Emergency departments are an important touchpoint for the delivery of and the linkage to evidence-based services for a high-risk population. These services might include initiating medications for opioid use disorder, providing naloxone, timely linkage to outpatient treatment, and addressing social determinants of health. A standardized approach, such as a checklist, might improve the delivery of care although patient autonomy should be respected. Providers in this setting could benefit from educational interventions, as many did not see treating opioid use disorder as the role of emergency departments and others questioned the effectiveness of medications as a treatment for this disorder. Peers working alongside clinicians are likely to facilitate the delivery of these services.

- For scientists: This was a qualitative study of clinical staff and senior management in a subset of emergency departments in Rhode Island. Future studies could also include the perspectives of peer support specialists and people who use drugs to better understand how delivery of services could be improved under this state policy that requires a minimal level of care for individuals with opioid use disorder presenting to the emergency department. State policies mandating that certain services be provided have potential to increase the delivery of and the linkage to evidence-based services for a high-risk population, and future studies could employ a mixed methods study where qualitative findings are accompanied by data on patient utilization of services and outcomes to assess the impact of these policy changes.

- For policy makers: The study’s findings were in the context of a statewide policy for treating overdose and opioid use disorder in all of Rhode Island’s emergency departments and hospitals. Currently, there are 14 state policies mandating that certain services be delivered to individuals with substance use disorders in the emergency department, ranging from requiring screenings to making medications available. These types of state policies leverage an important touchpoint for delivering evidence-based services to individuals with opioid use disorders presenting to the emergency department and may be promising in standardizing these services and helping to overcome myriad barriers to treating these individuals in this setting, such as provider apathy, stigma, and mistreatment.

CITATIONS

Collins, A.B., Beaudoin, F.L., Samuels, E.A., Wightman, R., & Baird, J. (2021). Facilitators and barriers to post-overdose service delivery in Rhode Island emergency departments: A qualitative evaluation. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 130, 108411. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108411