Expanding overdose prevention sites in Vancouver, Canada, has beneficial health impacts

To help combat the record-breaking rates of drug overdose deaths, Canada implemented 20 overdose prevention sites across British Columbia, with 5 in Vancouver. Overdose prevention sites are a type of supervised injection service that are less regimented and have fewer barriers than traditional supervised injection services. The researchers in this study investigated the impact of this implementation in Vancouver on health outcomes.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

In Canada and the United States, drug overdoses continue to negatively impact communities and break records. In British Columbia, for example, the annual overdose death rate increased by 84% from 2015-2016. Most recently, in the United States, over 100,000 people died from drug overdoses in 2021 alone. Harm reduction programming, such as supervised injection services (also called supervised consumption sites), have been established to help address this wide-scale problem. Sites such as these provide private spaces where individuals’ drug use is monitored by trained staff and sterile equipment is provided. Studies have shown links between these sites and reductions in the number of overdose deaths and emergency room visits, as well as reductions in a number of other drug use practices that can increase the risk of infectious diseases. To date, though, studies have not been designed in such a way that we can declare these harm reduction services actually are responsible for causing these reductions. Part of the challenge is that it’s not easy to conduct randomized controlled trials where some patients would be randomized to use these types of services and some not. Nevertheless, short of that, research designs that can better isolate any beneficial effects related to supervised consumption sites will be able to help inform the clinical and public health value of scaling up these services to increase the likelihood of greater access and engagement.

In 2016, Canada implemented expansion of a particular type of supervised injection services known as overdose prevention sites. While some use the terms supervised consumption/injection sites (or safe injection facilities) and overdose prevention sites interchangeably, in this study the research team makes a distinction between the two.

Overdose prevention sites are similar to supervised injection sites in that they are places where individuals are provided with sterile equipment to inject drugs and are monitored, thereby preventing the risk of adverse effects such as overdose and disease infection. However, overdose prevention sites are more informal and less regulated than supervised injection sites because they are often staffed by peers rather than mental health clinicians, do not offer many clinical services, and allow certain drug use practices that are not allowed at supervised injection sites. Accordingly, there are generally less barriers to accessing services provided by overdose prevention sites than there are to accessing services provided by supervised injection sites.

Evaluation of the impacts of implementing overdose prevention sites are needed to assess if they are meeting their goals of reducing the harms associated with drug use. Such evaluations can help inform policy decisions as to whether they should continue to operate and expand in countries where they currently exist or start to operate in countries where they are not currently available. Researchers in this study examined the health impacts of implementing 5 of these sites in Vancouver, Canada, among people who have used or injected illicit drugs.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

Researchers drew data from two large ongoing studies in Vancouver, Canada: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS; includes adults over the age of 18 who are HIV- and injected drugs in the previous month) and the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS; includes adults over the age of 18 who are HIV+ and used illicit drugs other than or in addition to cannabis in the previous month). In these studies, interviewers asked participants questions about their demographics and drug use behavior at a baseline and every 6 months thereafter.

To study the health impacts of expanding the number of overdose prevention sites in Vancouver, the study period was defined as the 23 months before expansion and the 23 months after (i.e., pre- and post-expansion), excluding the month of expansion (December 2016), for a total of 46 months of data. Participants’ data was included in the analyses for the present study if they had at least one interview during the pre-expansion period (January 1, 2015 through November 30, 2016) and one during the post-expansion period (January 1, 2017 through November 30, 2018) where they reported injecting drugs in the previous 6 months. In total, data from 745 participants were analyzed. The main outcomes of interest were use of supervised injection services, sharing syringes, injecting drugs in public, and participating in addiction treatment.

The researchers used a type of statistical analysis that allows them to compare actual, observed outcomes following the expansion of sites with outcomes that would be expected if the number of sites were not expanded. This analysis also allows the researchers to determine both immediate and gradual changes over time in the four outcomes of interest during the post-expansion period compared to the pre-expansion period.

Of the 745 participants included in this study, 39.7% identified as women and 59.6% were White. Participants were middle-aged (median age was 47) at the time of the baseline interview.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

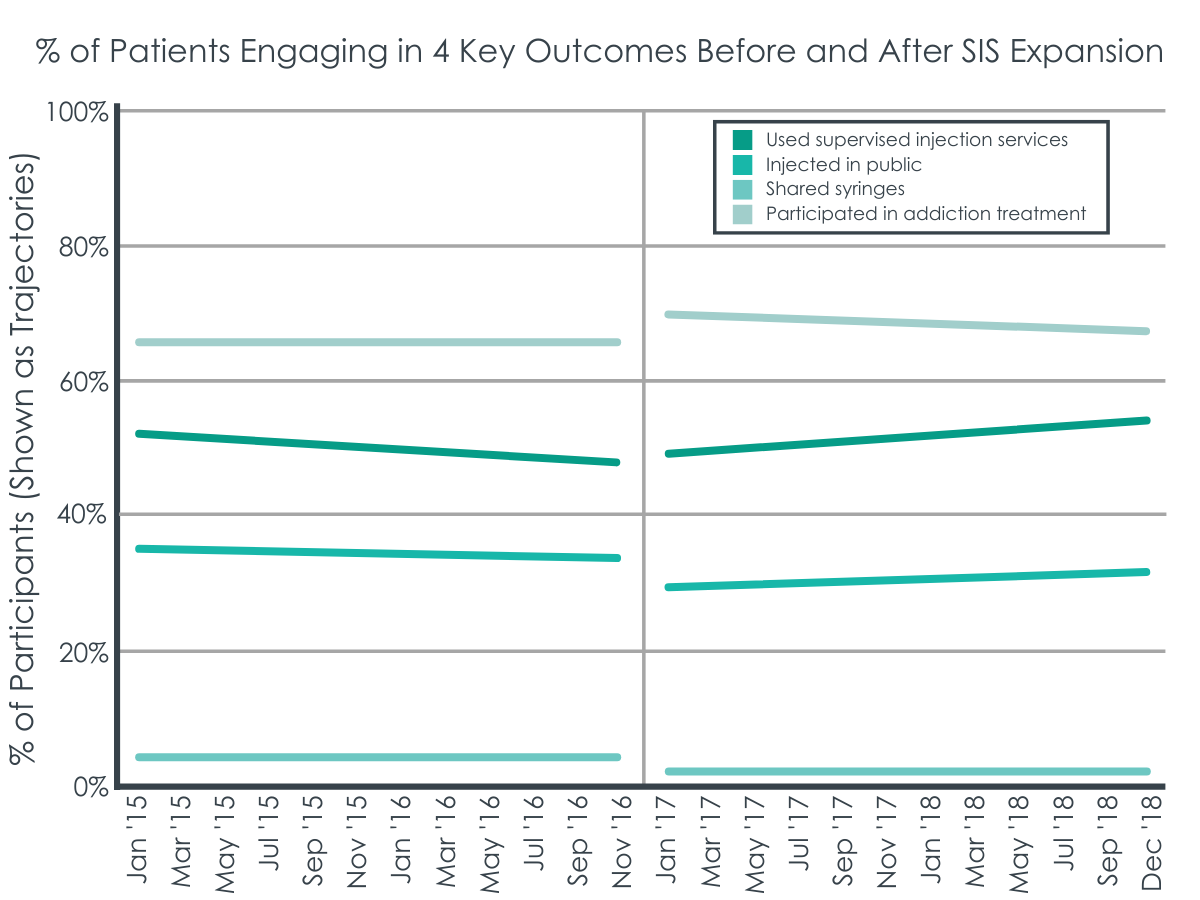

Use of supervised injection services increased immediately after the expansion of overdose prevention sites and continued to gradually increase.

At the beginning of the pre-expansion period (January 2015), the monthly proportion of participants who reported recently using supervised injection services was 50.8%, which decreased to 41.4% at the end of the pre-expansion period (November 2016). The expansion of sites occurred in December 2016, and in the month immediately following expansion (January 2017), use of supervised injection sites increased to 47.8%. Use of the sites continued to increase by approximately 0.7% per month. The estimated percentage of participants who reported using services 6 months after expansion was 49.0%, which is 10.6% higher than what would be expected if the number of sites had not expanded.

Participation in addiction treatment increased immediately after the expansion, but there were no further increases over the follow-up period.

At the beginning of the pre-expansion period, the monthly proportion of participants who reported participating in addiction treatment was 64.6%. There were no substantial changes in treatment participation through the pre-expansion period. In the month immediately following expansion, treatment participation increased to 69.1%. While there were no further increases in addiction treatment participation, the estimated percentage of participants who participated in treatment 6 months after the expansion was 68.6%, which is 7.1% higher than what would be expected if the expansion had not occurred.

Sharing syringes and injecting drugs in public both decreased immediately in the month following implementation, but there were no further increases over the follow-up period.

At the beginning of the pre-expansion period, the monthly proportion of participants who reported sharing syringes was 4.4%. There were no substantial changes in sharing syringes through the pre-expansion period. In the month immediately following expansion, the percentage decreased to 1.9%. While there were no further decreases, the estimated percentage of participants who reported sharing syringes 6 months after the expansion was 2.2%, which is 3.1% lower than what would be expected if the expansion had not occurred.

For public injection, the monthly proportion of participants who reported doing so at the beginning of the pre-expansion period was 36.2%. There were no substantial changes in the percentage of participants reporting publicly injecting drugs through the pre-expansion period. In the month immediately following expansion, the percentage decreased to 30.7%. While there were no further decreases, the estimated percentage of participants who reported publicly injecting drugs 6 months after the expansion was 29.4%, which is 5.9% lower what would be expected if the expansion had not occurred.

Figure 3 adapted from Kennedy, Hayashi, Milloy, Compton, & Kerr, 2022. After implementation of supervised injection site expansion between November of 2016 and January of 2017, changes were seen in trajectories and values of 4 key outcomes. The use of supervised injection sites increased, injecting drugs in public decreased, sharing of syringes decreased, and participation in addiction treatment increased.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Following expansion of less formal, peer-run overdose prevention sites in Vancouver, BC, Canada, the monthly percentage of participants who reported using supervised injection services increased immediately and continued to gradually increase in the subsequent months. The monthly percentage of participants who reported participating in addiction treatment also immediately increased and stayed higher, while reported public injection and sharing of syringes decreased and stayed lower. However, there did not appear to be any further changes in the following months.

Because use of supervised injection services increased immediately in the month after expansion, and continued to increase, there may be gaps in the coverage of existing services that the expansion helped to fill, as well as reducing the barrier of location. Further, overdose prevention sites may be preferred among some people who use drugs over other types of supervised injection sites, given that certain drug use practices are allowed there that are not allowed elsewhere. Likewise, overdose prevention sites may be preferred by some because of peer staffing instead of clinical staffing, which may promote greater comfort and safety. However, it should be noted that the study findings suggest that both types of services are needed, because use of overdose prevention sites were included in the definition of supervised injection services that participants were asked about. Accordingly, this suggests an additive effect of all types of supervised injection services together, rather than one being better than the other. Terminology may play a role in the public’s support of services, however. Specifically, using the label “overdose prevention sites” as opposed to “safe consumption sites” or “safe injection facilities” has been associated with higher levels of public support for the opening of such facilities, especially when paired with additional information, and legalization, even though they referred to the same service in those studies.

The findings of this study also add to the number of existing studies where researchers have demonstrated links between use of supervised injection services and increases in addiction treatment. Although the researchers in the current study do not fully understand the reasons for this since overdose prevention sites are not staffed by mental health professionals, one possible explanation is that the peers who do work at the sites have expertise and lived experiences that may allow them to promote treatment.

Similarly, this study’s findings further build upon the evidence showing associations between decreases in the number of people who inject drugs publicly and share syringes with greater availability of supervised injection services. This suggests that such services may provide alternatives to people who would otherwise publicly inject drugs and share syringes by offering a non-public space to use as well as sterile injection equipment.

Taken together, this study’s findings demonstrate beneficial impacts of expanding overdose prevention sites on four important health outcomes. Immediately and subsequently following expansion, use of supervised injection services increased. Immediately following expansion, addiction treatment increased while public injection and syringe sharing decreased. Future research is needed to replicate these findings in other settings and, if this effect is repeated, to determine why participants experience benefit in the short-term, but not over time.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- Because data were drawn from ongoing studies instead of taking a random sample from the community, study findings may not generalize to other people who use drugs.

- An average of only 92 observations per month were collected. Small sample sizes can limit the precision of the results and introduce noise.

- The researchers did not adjust the analyses in a way that would account for the same participants being studied at multiple time points.

- An external control group was not used, which limits the extent to which a causal association can be found. It also means that the findings might be explained by other factors not examined in the study.

- The researchers did not directly assess the impact of expanding overdose prevention sites on harms related to overdoses.

- Due to low monthly overdose deaths, the researchers were not able to examine if expanding overdose prevention sites had an impact on deaths.

BOTTOM LINE

Following expansion of overdose prevention sites in Vancouver, Canada, researchers found beneficial impacts on four important health outcomes. Use of supervised injection services increased immediately and subsequently in the months after expansion. Addiction treatment engagement immediately increased while public injection and syringe sharing decreased in the first month after expansion. These positive outcomes did not continue to increase over time, but were maintained at the more beneficial level.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: The study findings suggest that individuals who inject drugs may benefit from doing so in supervised injection sites, where harms are likely to be reduced and treatment may be promoted by peers with lived experience. However, these sites are currently only operating in a limited number of countries and therefore, access may be limited. Still, individuals who inject drugs may use these findings to prevent harms by engaging in practices that are similar to those offered by the sites, such as monitoring peers’ use, using sterile equipment, having ready availability of naloxone (Narcan), and not using in public.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Treatment professionals can help promote awareness of supervised injection services to their clients who use drugs but do not want to stop or cannot stop, if services are available nearby, as findings here and elsewhere suggest that use of such services may reduce harm. If services are not available nearby, however, treatment professionals can encourage their clients to engage in practices similar to those offered by the sites, such as never using alone, monitoring peers’ use, using clean equipment, having ready availability of naloxone, and not using in public. Consuming drugs in places like these sites that focus on the person and meets them “where they are,” from a readiness to change perspective, can result in them eventually seeking formal treatment for addiction.

- For scientists: Given that the current study was not able to examine the impact of expanding supervised injection services on overdose-related harms and deaths, future research is needed to examine these important impacts. Further, there were immediate and continued increases in the use of supervised injection services, but the beneficial changes in the 3 other outcomes (addiction treatment participation increase; decreases in public injection and syringe sharing) were only observed immediately after the expansion. Additional research is needed to examine if other factors beyond the expansion could account for the immediate benefit.

- For policy makers: Because the study findings suggest beneficial impacts of implementing supervised injection services, policy makers at the federal level in the United States can write legislation to legalize such services. However, given the limitations of this study (such as not examining the impact on overdoses), and that sites such as these are not federally legal yet in the United States, funding is also needed to evaluate them in the US and examine their cost-effectiveness. Likewise, policy makers in other countries where services are not yet legal can create policies to legalize them. In countries where services are legal, such as Canada, Europe, and Australia, policy makers can create policies that allocate funding for the implementation and scientific evaluation of supervised injection services.

CITATIONS

Kennedy, M. C., Hayashi, K., Milloy, M. J., Compton, M., & Kerr, T. (2022). Health impacts of a scale-up of supervised injection services in a Canadian setting: an interrupted time series analysis. Addiction, 117(4), 986-997. doi: 10.1111/add.15717