Internet-based interventions can help individuals manage heavy drinking, but do they save employers and society money?

Heavy alcohol use is associated with substantial economic costs to employers and society. Internet-based interventions can be helpful and low cost. This study explored whether they can also save employers and society money by increasing people’s productivity and reducing costs related to healthcare for alcohol-related problems.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Heavy alcohol use is associated with substantial economic costs for society, with approximately half of these costs attributed to sick leave, reduced job performance, early retirement, and involuntary unemployment. Given employers bear much of the brunt of the economic impact of excessive alcohol use, programs that help employees address problematic drinking can benefit employees, employers, and society as a whole.

Internet-based interventions are a promising option for employers wanting to give their employees access to evidence-based interventions designed to reduce alcohol-related problems. This is because such interventions can be delivered at relatively low cost and provide confidentiality and convenience, and have been shown to be helpful in reducing alcohol consumption.

Though the cost savings to patients of internet-based interventions (versus traditional in-person treatment with a provider) have also been fairly well documented, it’s not yet well understood if these interventions reduce financial costs to employers or society as a whole. Additionally, it’s not clear whether enhancing these internet-based interventions with clinician coaching (i.e., a guided internet-based intervention) is worth the additional cost.

The researchers evaluated the cost-effectiveness of both a clinician guided and an unguided internet-based intervention for problematic alcohol use, in terms of potential costs and savings to employers and society more broadly.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a secondary analysis of data from a three-arm, randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of an internet-based intervention among employees with and without a clinician who helped participants adhere to the internet intervention (“adherence coaching”) in order to reduce alcohol consumption. These were both compared to a waitlist control group with unrestricted access to treatment as usual. The study was conducted in Germany between 2014 and 2016 with a total sample size of 432 volunteer participants recruited from the community.

Eligibility criteria included being 18 or older, employed, and drinking at least 14 (women) / 21 (men) standard units of alcohol per week. Participants also had to score a minimum of 8/6 for men/women on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), which reflects hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption. Exclusion criteria included any past psychosis or drug dependence, high suicide risk, or current treatment for alcohol related problems or work-related stress.

Study participants were randomly assigned to internet-based intervention with adherence coaching (i.e., guided), or internet-based intervention without adherence-focused guidance (i.e., unguided), or be waitlist controls.

The internet-based alcohol intervention consisted of 5 weekly modules based on evidence-based treatments for alcohol use disorder, including motivational interviewing, cognitive and behavioral methods to control drinking behaviors and relapse prevention. In addition, the intervention contained trainings on emotion regulation.

Participants in the guided condition were also supported by an eCoach (i.e., a trained mental healthcare provider). Guidance in this study was primarily based on the supportive-accountability model of guidance in internet interventions, which argues that e-interventions will be most effective when paired with coaching that supports the individual, creates accountability, and increases motivation. In this study, this support was provided through adherence monitoring and feedback on demand that was provided within 48 hours of request.

Though people were not allowed to participate in the study if they were already engaged in treatment for alcohol related problems or work-related stress, participants were not constrained from beginning other forms of treatment after starting in the study.

A successful drinking outcome was defined as a participant having consumed no more than 14 (for women) or 21 (for men) standard drinks per week (called “low-risk” drinking in this study) at post-treatment and over 6-month follow-up. Health-related quality of life was measured using the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL-8D) at baseline, post-treatment and 6-month follow-up. The AQoL-8D measures health-related quality of life across eight dimensions (independent living, relationships, mental health, coping, pain, senses, self-worth and happiness) and generates patient preference-based utilities on a scale of 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs; often pronounced “qualies”)—a generic measure of disease/disorder burden—was calculated for the 6-month follow-up period from AQoL-8D scores. In brief, a QALY is a standardized measure of the state of health of a person or group in which the benefits, in terms of length of life, are adjusted to reflect the quality of life. One QALY is equal to 1 year of life in perfect health.

Financial costs and savings were measured for both the employer and society. Costs/savings to employers were calculated based on the cost of delivering the internet-based alcohol intervention, as well as costs or cost reductions stemming from changes in absenteeism (missing work) and presenteeism (being at work but underperforming).

Financial costs/savings to society were calculated based on the cost of delivering the internet-based alcohol intervention, as well as health care, and patient and family and productivity costs. These data were derived from the TiC-P, a questionnaire that assesses costs associated with psychiatric illness.

At the time of conducting the study, the market price of the unguided internet-based intervention provided by a commercial health-care service provider was approximately US$93 per participant (using a conversion rate of €1 = US$1.10). The guided intervention cost US$206 per participant, including the time that eCoaches spent on coaching and administrative tasks, costs for internet site maintenance and hosting, technical support, and overheads.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Both the guided and unguided internet-based alcohol interventions produced better outcomes versus waitlist controls.

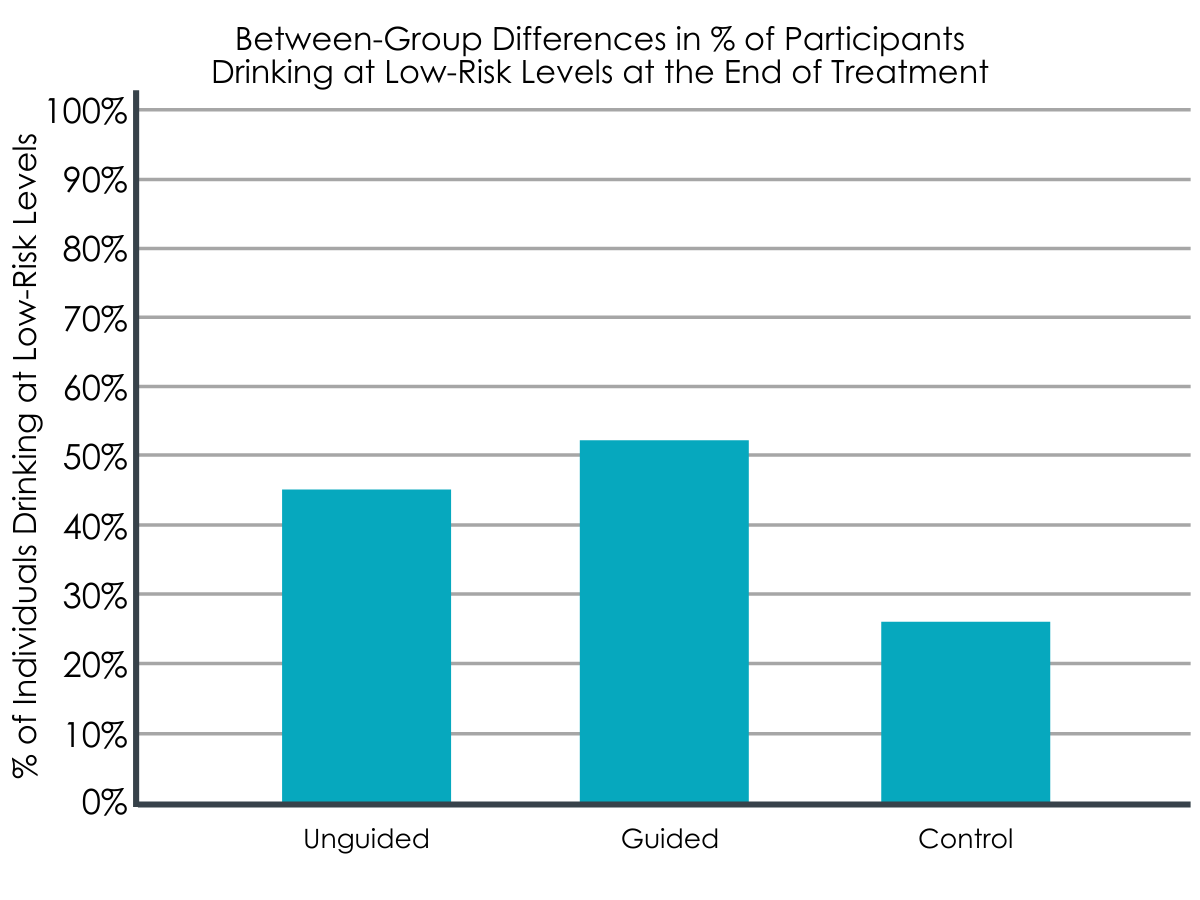

At 6-month follow-up, participants in both intervention groups were more likely to be drinking at low-risk levels (unguided: 45.2%; guided: 51.4%) compared to the waitlist control group (26.4%). Additionally, at 6-month follow-up, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were significantly higher in the guided (0.359 QALYs) and unguided intervention groups (0.359 QALYs), compared to the control group (0.342 QALYs)(range score of 0= death and 1= perfect health).

The waitlist control group cost employers the least in terms of absenteeism, while the guided internet-based alcohol intervention cost employers the least in terms of presenteeism.

Over the 6-month follow-up period, direct medical, patient, and family costs were similar for all three groups, meaning no group incurred significantly more healthcare related expenses than the other.

With regard to absenteeism costs, the waitlist control group (US$614) performed better than both intervention groups (unguided: US$723; guided: US$733). However, the guided intervention group had the least presenteeism costs (US$558) compared to the unguided intervention group (US$709) and the control group (US$687).

From the employer’s perspective, the guided intervention cost more, but was better value in terms of return on investment.

In terms of cost to employers, after factoring in costs due to absenteeism and presenteeism, the guided internet-based intervention cost employers US$206 per employee, while the unguided intervention cost US$86 per employee.

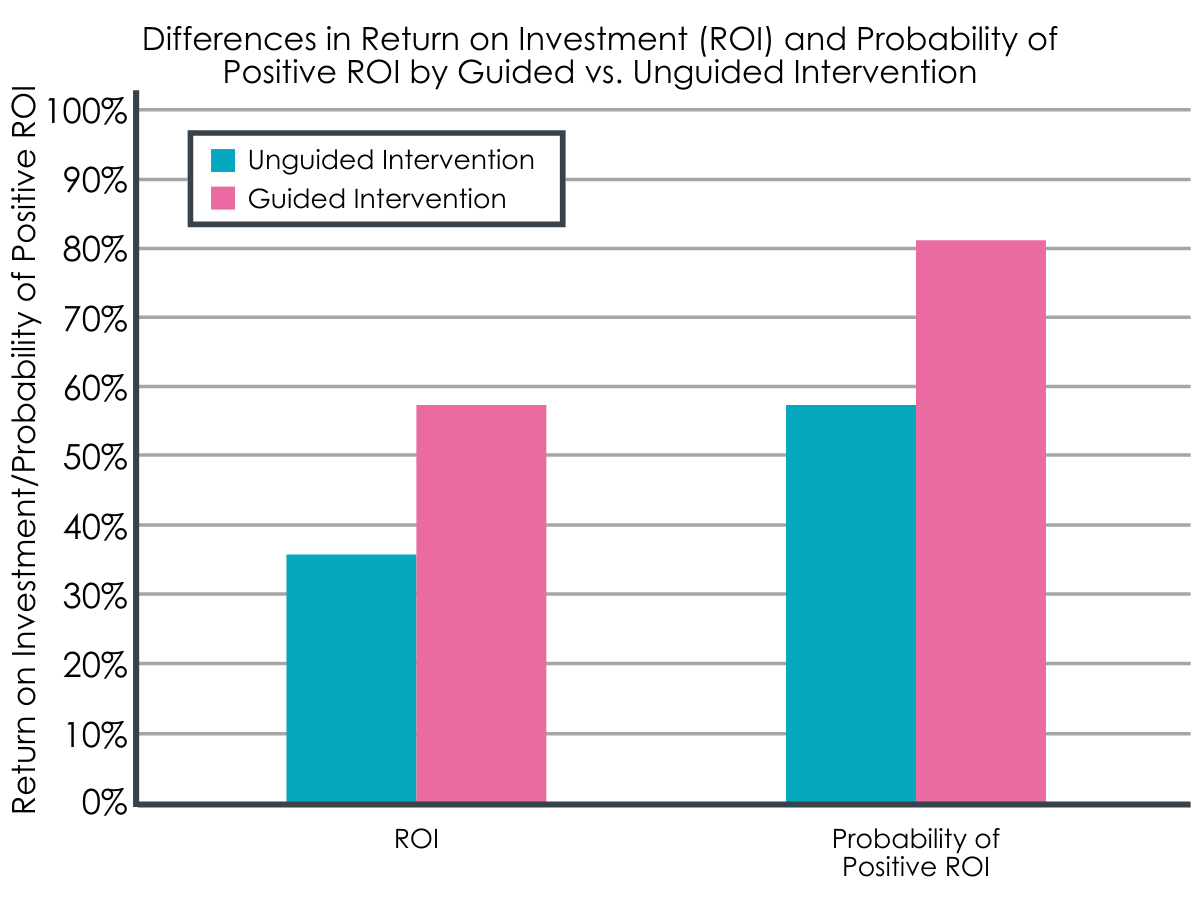

The unguided internet-based intervention showed a net benefit to employers of +US$32 per participant, while the guided internet-based intervention showed a net benefit of +US$119 after factoring in costs related to absenteeism and presenteeism. The return on investment was 36% and 58%, respectively. Further, the probability of a positive return on investment was 58% for the unguided, and 81% for the guided intervention meaning both interventions, but particularly the guided intervention, produced a reliable, positive return on investment.

From a societal perspective, being on a waitlist and not receiving the internet intervention cost more money and had little impact.

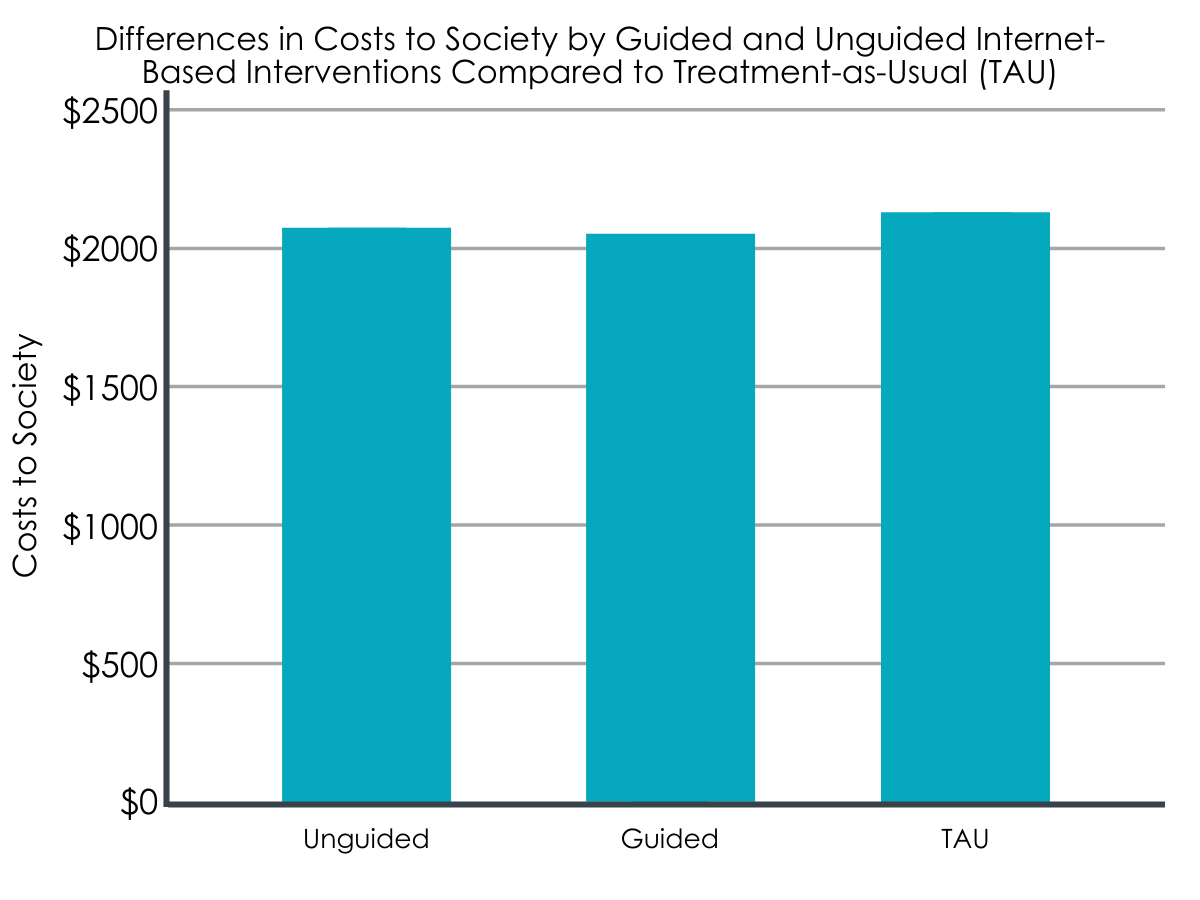

Regarding costs to society, waitlisted controls receiving treatment as usual yielded the smallest effects in terms of treatment response and quality of life years gained and did so at higher costs compared to both the guided- and unguided-internet intervention groups.

Specifically, treatment as usual was estimated to cost society US$2,120 per participant, while the guided and unguided internet-based interventions cost US$2,036 and US$2,009 respectively per participant.

Yet, as noted above, the guided and unguided internet-based interventions had treatment response rates (in terms of number of people drinking at low risk at follow-up) of 51.4% and 45.2% respectively, while the waitlist control group had a response rate of 26.4%.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

These findings are notable for a number of reasons. Firstly, they add to a growing body of evidence on the clinical utility of internet-based interventions to address alcohol use problems. Not only did both the guided and unguided internet-based interventions produce better results than waitlisted treatment as usual in terms of reducing high-risk drinking, they also appeared to do slightly better in terms of quality-adjusted life years (QALY’s) at 6-month follow-up. At the same time, this difference was small and may not translate into clinically meaningful differences.

Notably, the results of this study conducted in Germany were much like findings for a similar study conducted in the United States, suggesting these kinds of interventions have utility in a range of cultures, though more research is needed to determine how effective these kinds of interventions may be in non-western societies. Additionally, the low-risk drinking outcome used in this study is consistent with European guidelines (i.e., no more than 14 drinks for women and 21 for men per week), but different to guidelines in the United States that suggest no more than 7 drinks for women and 14 for men per week.

Perhaps most interestingly, while the guided internet-based intervention cost employers slightly more than the unguided intervention and there was no cost to the employer associated with treatment as usual, the guided intervention ultimately produced the best return on investment.

Specifically, though the guided intervention cost employers US$206 per employee, it ended up producing a net benefit to employers of +US$119 per employee. Further modeling analyses showed that the guided intervention was likely to have a positive cost-saving effect most of the time (i.e., in about 80% of cases who receive it). These findings align with previous studies in clinical samples that have shown that more intensive internet-based interventions for alcohol and other substance use disorders can be cost-effective adjuncts to addiction treatment as usual.

Cost benefits were also observed from a societal perspective, with both the guided and unguided interventions financially costing society slightly less than treatment as usual but producing twice the response rate in terms of number of people drinking at low risk at follow-up. This speaks to the value of proactively addressing drinking problems in society. Though substance use treatments/interventions may cost money up front, they usually save individuals and systems money in the long run. Additionally, treating individuals with drinking problems before they develop alcohol use disorder invariably saves unnecessary individual and family suffering, and helps reduce premature mortality, financial costs, and other costs to society.

Curiously, waitlisted controls cost employers the least in terms of absenteeism but more in terms of presenteeism compared to the internet-based interventions. It could be that getting treatment made participants more attuned to their emotional functioning and well-being. Absenteeism may be, in this instance, a marker of ‘self-care’, wherein participants were taking days off to prioritize their health and well-being. More research is needed however to tease out this unexpected finding.

It should be noted, too, that although there was a comparative benefit for the intervention groups (compared to the waitlist control group), only about half of those individuals in those intervention groups met the intended ‘low risk’ drinking goal at follow-up. Thus, more needs to be learned about how best to improve the intervention to meet the needs of those not responding to it.

- LIMITATIONS

-

As noted by the authors:

- Costs to employers were not exhaustively explored. For instance, premature death or accidents were not considered in the analysis.

- Similarly, from the societal perspective, crime and criminal justice involvement were not considered.

- Although the sample size in this trial was sufficient to demonstrate comparative effectiveness, much larger sample sizes are required for hypothesis testing in economic studies due to the large variance of costs relative to normally distributed health effects.

- The internet-based interventions in this study were compared to a wait-list control group. However, pharmaco-economic guidelines recommend standard care (e.g., brief face-to-face alcohol interventions) as comparator.

- On average, the study participants were highly educated. Evidence suggests that better treatment adherence is predicted by higher education. As such, the researchers’ findings may not apply to individuals with lower levels of education.

- The researchers did not conduct diagnostic interviews to formally identify participants with alcohol use disorder. At the same time, including participants with a wide range of alcohol consumption patterns (some of whom may actually have had alcohol use disorder) reflects the range of drinking patterns in the real world.

- As is common in these sorts of studies, the research context may have led to self-selection of individuals who might be more motivated to engage in internet-based interventions than is assumed outside a research context. As a result, findings might not be generalizable to the wider target population.

BOTTOM LINE

Internet-based interventions produced better drinking and disease/disorder burden outcomes at 6-month follow-up versus treatment as usual. Additionally, these internet-based interventions were found to be both cost-beneficial (i.e., the financial benefits exceed the intervention costs) and cost-effective (i.e., the health effects gained presented good value for the money invested) for employers and society. Further, the guided, eCoaching intervention was cost-effective, and was the best option overall of the three approaches tested. More studies with longer follow-up periods are needed however to better understand whether these short-term benefits translate into long-term benefits, and how these kinds of interventions might benefit individuals with moderate to severe alcohol use disorder.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Internet-based interventions for heavy alcohol use appear to be helpful for reducing high-risk drinking; however, more work is needed to assess the potential benefits of such brief interventions for individuals with more severe drinking problems (i.e., moderate-severe alcohol use disorder). For individuals with more severe drinking problems, more intensive internet-based interventions like CBT4CBT and Overcoming Addictions might be more effective, especially in combination with other forms of treatment. It is also important to note that the researchers’ findings may not generalize to other web-based interventions for drinking problems, which are likely to vary across multiple dimensions.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Internet-based interventions for heavy alcohol use appear to be helpful for reducing high-risk drinking and might possibly be useful in conjunction with existing substance use problem treatments. However, more work is needed to assess the potential benefits of such brief interventions for individuals with more severe drinking problems (i.e., moderate-severe alcohol use disorder). For individuals with more severe drinking problems, more intensive internet-based interventions like CBT4CBT and Overcoming Addictions might be more helpful, especially in combination with other forms of treatment. It is also important to note that the researchers’ findings may not generalize to other web-based interventions for drinking problems, which are likely to vary.

- For scientists: Internet-based interventions for heavy alcohol use appear to be helpful for reducing high-risk drinking, however, more work is needed to understand how to increase the impact of such interventions in these employed populations as well as assess the potential benefits of such brief interventions for individuals with more severe drinking problems (i.e., moderate-severe alcohol use disorder). Further studies should thus assess the long-term clinical and cost-effectiveness of internet-based interventions for problematic alcohol use to shed light on the duration of their effects and longer-term benefits and cost effectiveness and whether and how often these or similar types of interventions might need to be repeated over time.

- For policy makers: Internet-based interventions for heavy alcohol use appear to be helpful for reducing high-risk drinking among employed individuals with mild-moderate levels of alcohol use. Further these interventions can be delivered at low-cost relative to treatment as usual and were shown in this study to save employers and society money. Expanding health insurance to cover such internet-based interventions would likely improve public health and translate into cost savings to healthcare systems and society.

CITATIONS

Buntrock, C., Freund, J., Smit, F., Riper, H., Lehr, D., Boß, L., . . . Ebert, D. D. (2022). Reducing problematic alcohol use in employees: economic evaluation of guided and unguided internet-based interventions alongside a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 117(3), 611-622. doi: 10.1111/add.15718