Brief screening helps address future problematic alcohol use among adolescents

Adolescents who use alcohol earlier and more heavily have greater likelihood of developing an alcohol use disorder; screening tools can help intervene at the earliest possible stage to disrupt this progression. Screening tools that are relatively quick and straightforward to administer will be the easiest to incorporate into prevention and clinical settings. Examples developed for adults and tested across a wide variety of patients include the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and its shorter version, the AUDIT-C. This study examined the ability of the AUDIT and the AUDIT-C to predict future problematic alcohol use among Finnish adolescents.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Adolescents who use alcohol early (e.g., by age 14) and heavily are more likely to develop an alcohol use disorder. To intervene at the earliest possible stage before problematic use develops (i.e., prevention), clinicians can use brief and inexpensive screening tools to identify youth with elevated levels of alcohol consumption and connect them with the appropriate resources. Some validated examples developed for adults and tested across a wide variety of patients include the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and its shorter version, the AUDIT-C. Although these tools identify existing problematic alcohol consumption, it is unclear whether they can also be used to predict future alcohol use disorders. This study examined the ability of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and its shorter version (AUDIT-C) to predict whether Finnish adolescents with elevated scores on these tests indicated problematic alcohol use one year later.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a secondary data analysis of data collected in the Adolescent Depression Study, a study with Finnish youth ages 13-19 being clinically treated for major depressive disorder conducted from 1998-2001. In this study, the research team collected data from 217 adolescents with major depressive disorder. They also identified a group of “control” participants, i.e., sex and age matched youth without depression. Youth were assessed at baseline and after 1 year. The authors only included youth who completed the baseline and 1-year follow-up in the analysis for this study.

There were three primary measures. First, the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to assess levels of drinking at baseline by asking 3 questions on the amount and frequency of drinking, 3 questions on alcohol dependence, and 4 on problems caused by alcohol. A summary score indicating risk for an alcohol use disorder can be created from these items. Youth’s score on the full 10-item measure (Finnish Translation) were calculated as well as their score on the 3-set subset of items representing the short version of the AUDIT (AUDIT-C). The AUDIT-C just focuses on alcohol consumption behavior (how much and how often) and not on the consequences of drinking. The Beck Depression Inventory assessed depression symptoms. The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS-PL) is a structured interview for youth ages 6-18 years based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. The K-SADS-PL was used to capture alcohol use at baseline and the one-year follow-up: alcohol use was reported as “No use”, “non-problem use”, “problem use”, “alcohol abuse”, and “alcohol dependence”.

In the analysis, a participant was considered AUDIT-positive for an alcohol use disorder if the participants had a score of 5 or higher on the full 10-item scale or a score of 3 when the scale was reduced to the 3-item, AUDIT-C version; if not meeting these criteria, a participant was considered to be AUDIT-negative. Although the original AUDIT research with adults used higher cut-off points (indicating more harmful alcohol use behavior), the research team had chosen the cut-off points for this study based on previous research they conducted with a similar youth population. The indicator of AUDIT-positive/negative was used to predict the outcome of problematic alcohol use at one year. The outcome data were dichotomized to any problem use (i.e., participant reported “problem use”, “alcohol abuse”, or “alcohol dependence”) versus no problem use (i.e., participant reported “no use” or “non-problem” use). When examining the ability of the AUDIT and AUDIT-C to predict future alcohol problems, the research team used several control variables, i.e., sex, age, depression scores, and level of baseline alcohol use (K-SADS-PL) in the analysis to isolate the relationships between AUDIT status at baseline and problematic alcohol use.

This study’s sample was comprised of 337 adolescents (mean age = 16 years old) from Finland. Most of the sample was female (81%) and over half were patients in treatment for depression (n = 189).

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Youth with depression were more likely to be AUDIT-positive.

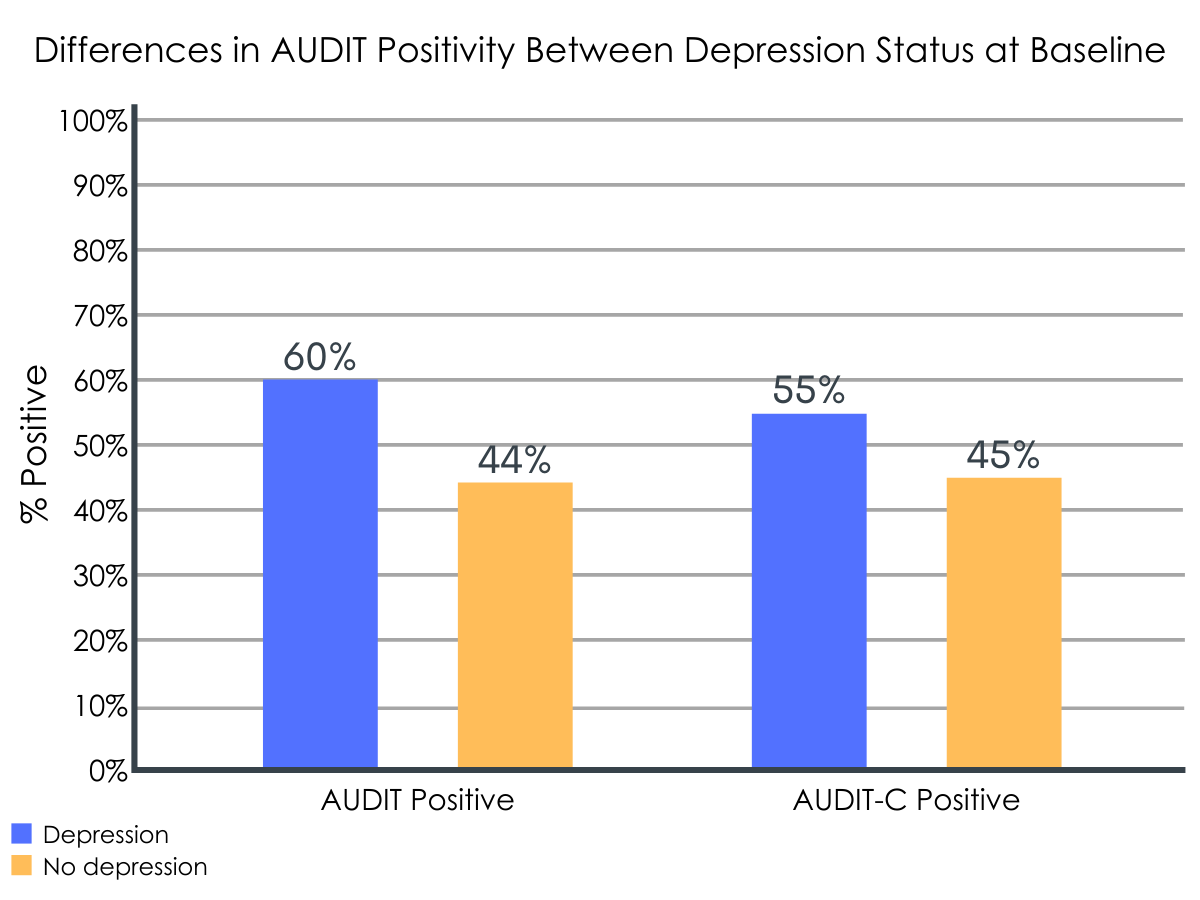

Sixty percent of the adolescents with depression and 44% of adolescents without depression were AUDIT-positive. Fifty-five percent of the adolescents with depression and 45% of adolescent without depression were AUDIT-C positive.

Figure 1.

Both tools were highly likely to detect future problematic alcohol use.

If a participant was AUDIT-positive on either tool (full or brief version) their odds of problem alcohol use one year later was nearly 7 times more likely than individuals who were not.

The AUDIT and AUDIT-C were highly sensitive in detecting future alcohol problem use (~0.8), meaning that individuals who were AUDIT-positive at their baseline visit were very likely (~80%) to have an alcohol problem 1 year later.

The tools only had medium accuracy (~0.6), indicating that they identified quite a number of false positives and false negatives. That is, only about 60% of individuals could have their level of future alcohol problem use accurately predicted from their AUDIT score 1 year prior; some youth tested positive but did not develop alcohol use problems, while other youth tested negative but did develop alcohol use problems.

Taken together, given the fact that the tools were highly sensitive to detect future alcohol problem use, these findings indicate that the tools are useful in clinical settings to suggest where youth might need referral to follow-up or further intervention.

Youth with depression were more likely to have problematic alcohol use at 1 year if they had an AUDIT-positive score at baseline.

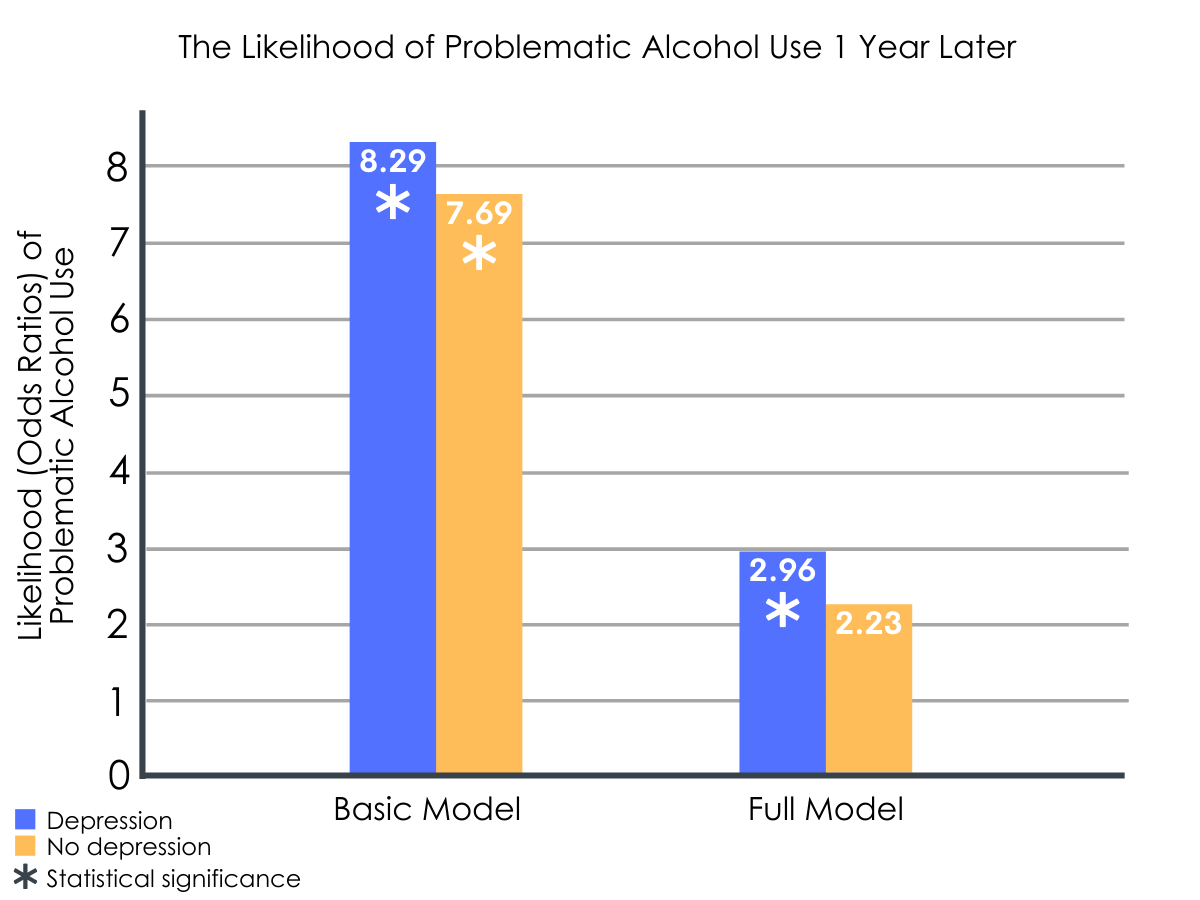

Although both depressed and non-depressed youth with AUDIT-positive scores were more likely than youth with AUDIT-negative scores to have problematic alcohol use 1 year later, in the full model with control variables which accounted for different amounts of alcohol use at baseline, only youth with depression were significantly more likely to have problematic alcohol use 1 year later.

Figure 2. Positive odds ratios indicate an increased likelihood of an outcome occurring, with higher value indicating higher likelihood. In the full model, where differing amounts of alcohol use at baseline were taken into account in the statistical analysis, only youth with depression were significantly more likely to have problematic alcohol use 1 year later.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

There have been recent recommendations in the U.S. not to use brief screening tools such as the AUDIT among adolescents because of the lack of evidence supporting their use; this study provides evidence to address this issue in its examination of the ability of the AUDIT and its shorter version, the AUDIT-C, to predict problematic alcohol use consumption one year later among Finnish adolescents.

The study indicated that when using appropriate levels for youth, similar to findings from a study of college-age participants, both tools were successful in identifying youth at risk of later problematic alcohol use. The findings also indicated that youth with depression were more likely than those without depression to have AUDIT-positive scores at baseline. Finally, AUDIT-positive scores at baseline were highly predictive of problematic alcohol use 1 year later and this finding was stronger for youth with depression even when baseline drinking levels were accounted for. These findings support research indicating that the AUDIT and its shorter version, the AUDIT-C, are useful in identifying youth at risk for developing problematic substance use; as well, the findings suggest that the tool may have unique ability to predict this for youth with depression. However, the rates of AUDIT scores were quite high in this sample of youth, with over 50% screening positive, a potential result of the AUDIT’s high level of sensitivity (80%) but only medium level of accuracy (60%) for predicting future alcohol problems.

It is also worth noting, however, that a small portion of those who screened AUDIT-negative did nevertheless have problematic alcohol use one year later suggesting that the tool is not 100% effective at detecting and predicting future alcohol problems. As well, given that some youth screened AUDIT-positive at baseline, a prime time for intervention, it is unclear what clinical intervention took place at that time (if any) to prevent youth from further engaging in problematic alcohol use, especially those youth who were already in treatment for depression. There are effective early interventions, such as screening and brief alcohol interventions, which may be useful to consider for future work with vulnerable youth.

- LIMITATIONS

-

- The authors used previously suggested cut-offs for generating the AUDIT-positive and AUDIT-negative scores; it is unclear whether there might be more appropriate cut-off scores (i.e., scores that are more predictive) on these measures for adolescents

- Most of the participants were female (81%) so findings may not generalize to boys.

- The follow-up is only for one year later and is only at one point in time; it is possible that some important youth changes in patterns of substance use were not captured during this follow-up window.

- Given that these data were collected 10 years ago, it is possible that some changes in clinical approaches since the time of this study may influence how these findings are disseminated.

- There may be specific characteristics of the Finnish context, which might not translate to other contexts, such as the United States.

BOTTOM LINE

This study found that both AUDIT and AUDIT-C are useful in identifying adolescents who may be in need of early intervention, provided the benchmarks used are appropriate to their age. And yet, it is important to remember that different groups of adolescents will have different resources and barriers leading to differing levels of alcohol use and related consequences; some characteristics such as mental illness are likely to result in elevated risk for problematic alcohol use. As well, although research has found that the AUDIT is useful for addressing problematic use among college students, it also demonstrated that scoring may need to be adapted for different genders, a consideration useful when considering different adolescent characteristics.

- For individuals and families seeking recovery: Any level of alcohol use among youth can lead to negative alcohol-related consequences or result in an alcohol use disorder and this is especially true for youth who have another mental health condition. Identifying alcohol consumption among youth and quickly supporting them in accessing appropriate intervention and/or treatment is necessary to disrupt this progression.

- For treatment professionals and treatment systems: Short tools for quickly identifying alcohol use among youth should be implemented in clinical settings, especially those clinical settings where youth with other behavioral diagnoses are present. In addition to the tools highlighted in this study, practitioners may be interested in using the CRAFFT screener tool which was developed specifically for adolescents. If used to identify problematic use early in the youth’s life, practitioners may be able to intervene and stop the progression from moving to more severe alcohol use.

- For scientists: There is a great deal of interest in developing the ability to identify strong predictors of problematic alcohol use, especially in settings where there is a captive audience (e.g., in clinical settings or mental health treatment programs). Although the AUDIT is a standardized tool developed for quickly identifying problematic alcohol use, future research should address whether different cut-off scores should be used for predicting problematic alcohol use among participants with certain characteristics (e.g., by gender, mental health comorbidity, age, co-morbid substance use, other mental health conditions). As well, it may be worthwhile to empirically compare adult-focused tools such as the AUDIT to adolescent-focused tools such as the CRAFFT screener tool to see which is more sensitive and accurate at identifying and predicting future problematic use.

- For policy makers: Previous research syntheses identified a gap in understanding the effectiveness of brief screening tools for youth alcohol consumption; although this study adds to the literature base, it is clear that funding should address this issue so that future studies can add to this base. As well, funding for research on treatment models that provide a variety of linkages between mental health and substance use disorder systems may help to further the ability for clinicians to better address both issues simultaneously.

CITATIONS

Liskola, J., Haravuori, H., Lindberg, N., Kiviruusu, O., Niemelä, S., Karlsson, L., & Marttunen, M. (2021). The predictive capacity of AUDIT and AUDIT-C among adolescents in a one-year follow-up study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108424. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108424